I took a new tack. “What’s a typical Como interview like?” I asked. “I know you’ve been through scores of them. What do they ask you?”

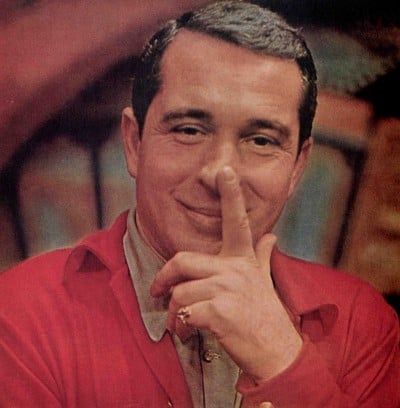

“I don’t have a lot to tell the average interviewer,” Como said. “So finally in desperation most of them ask, ‘How long have you been singing?’ Then I know it’s time for us both to leave. I’m a bad interview because, aside from making records and my radio and television activities, not a lot has happened to me in the past fifteen years. I’ve done nothing that I call exciting. I was a barber. Since then I’ve been a singer. That’s it.”

I eyed him. He wasn’t being mock modest; he meant it. I said, with what I thought was great restraint, “A lot of people would call making records and working in radio and television exciting.”

“Sooner or later,” he said, “all the interviewers get around to asking me, ‘Are you really all that relaxed, Perry?’ No matter what I tell them, they already know the answer. They have it written down at home on a piece of paper, ready to go to press. The usual line is: ‘Como’s personality is like warm maple syrup.’ Such interviews are probably why I’ve got a reputation for being the laziest entertainer since Stepin Fetchit. I’d just like one of those writers to follow me around for six months. They’d start panting quick.

“Once when I was making what is called a good-will tour for my sponsor, Kraft Cheese, I remember walking into a place run by an electrical-appliance dealer. The dealer was just launching a washing machine. There were twenty salesmen there, with the sales manager sitting behind the desk, clubbing them over the head with a sales pitch.

“One of my sponsor’s representatives said, ‘Why not go in and say hello to them?’ I said, ‘That’s silly. What can I say to a bunch of men who sell washing machines?’ But I walked in, and the first thing that I was asked was the stale question, ‘Are you really that relaxed, Mr. Como?’

“‘I’m as relaxed as this,’ I said. ‘Very few people, even mill hands, work as hard as I do.'”

He shrugged. “Do you think they believed me? I should have saved my breath. What was really going through their heads as they listened was, ‘I could be as relaxed as that if I worked only one hour each week.’ They don’t have enough courage to come out and say it to me unless they have half a bag on, but they think so. You work one hour a week. What’s so rough about that?”‘

He added thoughtfully, “Later I’ll give you a play by play of my week.”

“For one thing,” I said, “your responsibility for the people connected with your show, and their families, must rest right on your neck.”

“Actually,” Como said, “that weight’s on the directors and producers and all the other people who work with me, but I do have to be there.”

“I had lunch with a friend of yours yesterday,” I said, “a person who knows you very well. He came up with the notion that you’re not so much a classic case of relaxation as of equanimity. What do you think equanimity means?”

“I was just going to ask you,” Como said.

“Your friend said that you refused to be thrown by minor problems. Maybe that’s what he meant.”

Como told me, “I have my sleepless nights and my good moments and my bad moments just like anybody else. Take our rehearsals. Suppose I have a guest star and my guest isn’t doing too well. If everybody gets shook up by that, my whole show begins to rattle like worn-out machinery. I’ve found that if I stay calm myself, everybody tends to get calm.”

“I hope some of it rubs off on me,” I said.

“If I’m calm,” Como said, “I think that, as much as anything else, it has to do with maturity. After all, I’ve been around a hundred years. In this business you eventually reach a point where, if you’re doing your show with three cameras and two of them go dead, you ask yourself, ‘What can I do about it?’ If you’re honest with yourself, you’ll tell yourself, ‘Nothing.'”

“How do you know when a camera conks out?” I asked. “Are you looking at a monitor screen?”

“You can tell,” he said. “All of a sudden eight or ten guys start trying to patch things together while I’m trying to sing a song and look romantic. And there are nine other guys bringing things to the first guys. But I’ve learned that what can be trouble sometimes turns out to be fun. I tell the viewers, ‘We’ve got a little problem here video-wise, but if you stay with us, we’ll see if we can get the man who invented this thing out of bed and ask him to come down here to the studio and fix it.’

“I remember once when Guy Lombardo was on our show. He’d gone upstairs, thinking he had ten minutes to make a costume change. Nobody had told him that he had only three minutes. When he was through changing, he started down, only to get stuck in the automatic elevator. In the meantime, I was standing before our TV cameras saying, ‘Now, Guy . . .’ and there was no Guy. So I told our musical conductor, Mitchell

Ayres, ‘Mitch, you come up here and read Guy’s lines.’ Mitch read Guy’s lines, and I called him Guy. We’d finished a few lines of script when in walked Guy, all fiustered. He hurried over to me and rattled off his first line, and I had to tell him, ‘We’ve already done that one.’ He died. He didn’t know what was going on. But the rest of us thought it pretty funny. Fortunately our viewers did too.”

“I’ve heard that the Hearst TV columnist, Jack O’Brian, was the one who tagged you Mr. Nice Guy,” I said. “That name has stuck, hasn’t it?”

“Yes,” he said, smiling wryly. “Sometimes it’s hard to live up to, but I’d rather be called that than a heel—which reminds me of a story somebody told me a couple of days ago about Adolf Hitler. It seems that just before the downfall of Germany, Hitler called in the heads of his air force, his navy and his army, for an accounting. First he called on the air marshal, who clicked his heels and said, ‘Heil Hitler!” Hitler said, ‘Stop it with that Heil Hitler. What happens with the air crews?’ The air-force commander said, ‘My Fuhrer, we have only one Messerschmitt left.’ Hitler said, ‘You dummkopf. Stand over there at attention until I need you.’ Then Hitler asked the admiral for his report, and his top sea dog said, ‘Heil Hitler!’ and Hitler said, ‘Stop it with that Heil Hitler. What happens with the boats?’and the admiral said, ‘My Fuhrer, we have one canoe left.’ Hitler said, ‘Stand over there with that other dummy.’ Then the Fuhrer called in the guy who ran his ground forces. He said, ‘Heil Hitler!’ and Hitler asked. ‘What happens with the army?” The general said, ‘My Fuhrer, we have ten thousand soldiers on the left with bullets and no guns, and we have six thousand soldiers on the right with guns and no bullets,” and Hitler said, ‘Stand over there with those other two. Now I want to tell you three stupid fools something. I’m sick and tired of being such a nice guy!'”

“I’m interested in your durability,” I said. “Once you said, ‘Radio and TV seem to be my mediums. If I get lucky and do what people like, I’ll last. I hope I’ve got the right formula.’ But that still doesn’t explain your long years in broadcasting.”

“People,” he said, “go just so far with talent. After that, if you make it big on television, it’s because somebody’s watching over you somewhere. I’m sure somebody’s watching over me, because otherwise, what I have to offer isn’t great enough. After all, what do I do? I just sing a few songs.”

“You sing on tune and you sing pleasingly and as easily as breathing,” I said. “Let’s not knock those qualities.”

“I’m not knocking them,” he said. “I’m just telling you that you must have a little something extra going for you to keep you sticking around. People—elderly people and youngsters—still go through a routine I get a kick out of. I’ll be honest about it—I’m not above being excited when a kid comes up to me and stares at me and I can tell that he recognizes me. Something warm and gratifying happens inside of me, just as it does when an elderly woman sits down and writes me a grateful letter.”

“The nearest I’ve ever come to it,” I said, “was one afternoon in Brooklyn when I pulled up outside a television studio in a taxi, and a horde of youngsters bore down on me with their autograph books and pencils poised. They stopped, looked at me, then asked doubtfully, ‘Are you anybody?” I said no in a small voice and ran for the studio door. It was a humbling experience.”

Como chuckled at my remembered discomfort, and I said, ‘Maybe your durability can be explained by the fact that people see something in you that they like. I remember that one of the many writers who have interviewed you called you a ‘good man.” Does that sort of thing embarrass you?”

Como’s brow furrowed, and he said seriously, “I don’t know what that writer was talking about. Maybe he liked me because I liked him. Some people are dog lovers. I’m a people liker.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

A very nice article.I am sad that Perry Como is so underrated.Not producing scandals ,headlines in the tabloids and showing of is obviously the way to get forgotten.

Best regards

G.Bendel

Germany

Wonderful article. I remember listening to Perry on the radio with my Mother. I have many of his records.