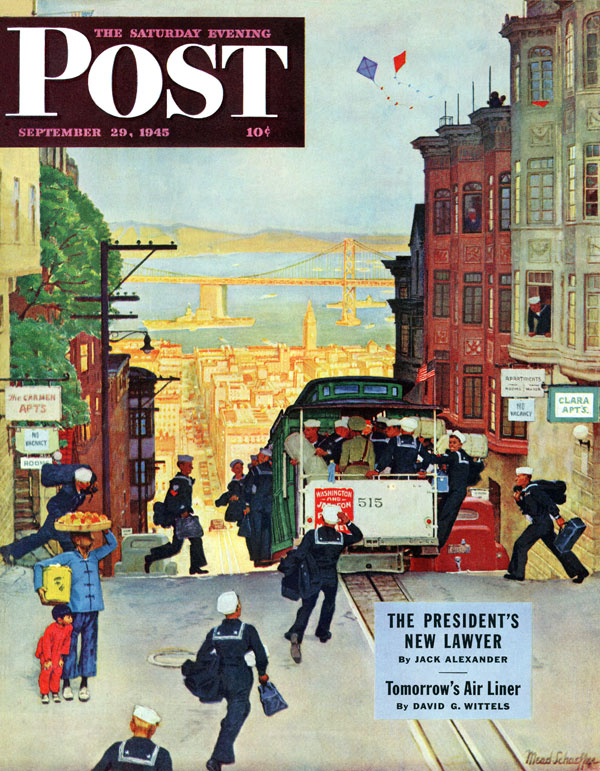

The Post cover that started a movement to save San Francisco’s endangered cable cars. Click here to view more Post covers featuring mass transit.

Occasionally, those interests come together to create a vision of the future. Such is happening in Normal, a town of 52,000 in Illinois and home to Illinois State University. This summer a new bus-train station opens in “Uptown Normal,” an area that had become run down and was losing businesses and residents. “The city council could have done what happened in the ’70s—new sidewalks and street lamps—but that’s like a dusting and cleaning. We wanted to be bolder,” explains Chris Koos, mayor of Normal. “We had several trains a day here, high-speed rail line on the horizon, so we decided to build upon our transportation system.”

City buses, regional Greyhound buses, and express buses to Chicago will operate out of Uptown Station and provide connectivity to the 10 Amtrak trains that stop daily. Illinois and Union Pacific Railroad are upgrading the line between Chicago and St. Louis for 110-mph service. There’s a proposal to build a light rail train from Peoria. Even the bike and pedestrian paths connect with the station. Corporations, including State Farm Insurance in nearby Bloomington, expect to use more transit and trains for business travel to Chicago. And the student travel on the trains, which has always been strong, is bound to increase. Students can ride bikes or walk from campus.

“We’re 120 miles from St. Louis; 150 miles from Chicago. Rail makes great sense. We expect more business travel and more commuters coming through the station,” says Koos.

The station was partly financed through a $22 million federal grant, but it has spurred nearly $150 million in related capital investment, including a hotel-conference center and a children’s museum. What occurred in Normal is known as transit-oriented development or TOD, in which public investment in transit stations leverages private development. TOD initially was a big parking lot next to a light rail station—a place where commuters parked their cars and boarded a train—but the concept has been expanded to retail centers, theaters, and condos and apartments, explains Smith.

Before he became director of Reconnecting America, Smith was mayor of Meridian, a small city in Mississippi that built an impressive, retro-looking rail-bus station with the aim of revitalizing its downtown and creating an attractive stop for the Crescent, the long-distance train running between New York City and New Orleans.

Meridian partnered with developers to designate historic and arts districts within walking distance of the station. Many vintage buildings were beautifully restored and some became repurposed as restaurants, shops, galleries, and apartments.

“Development around stations is a key to a successful transit system,” says Smith. “We have to be cognizant of streetscapes, walkability, and biking, too—really thinking about how people use these forms of transportation.”

The intermodal hubs in Normal and Meridian were built with federal grants and other government funds. Private developers typically piggyback with government spending but don’t fund transportation projects on their own. The risk is too great; the time horizons too long.

“It’s said that government exists to provide for people what they cannot provide for themselves. That is the nature of transportation,” Smith says. “The moment you step off your property for a trip to the store or doctor or to go to school, you are on public infrastructure.”

For all the shining examples of local efforts to build intelligent ways to travel, mass transit is in jeopardy. Most federal dollars for transit come from the Highway Trust Fund set up in the 1950s to funnel gas taxes and user fees into highway projects. Beginning in the 1970s, about one-quarter of the fund has been earmarked for mass transit.

The gas tax has not increased since 1993 and remains at 18.3 cents per gallon. Each year, inflation cuts into its spending power. Many states have delayed replacement and maintenance of roadways and bridges, but politicians of both parties have treated the gas tax like the proverbial third rail—touch it and die.

The Obama Administration has proposed more infrastructure spending and a new infrastructure bank to offer low-interest loans and leverage private money. It’s the type of public works initiative that has received bipartisan support in the past, but not this time. Just this spring, the Republican-led U.S. House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee proposed cutting mass transit entirely from the trust fund. Other transportation experts have suggested replacing the gas tax with user fees and charging motorists per mile driven.

Financing government-built infrastructure was a no-brainer for previous generations. And there may be no better time to do it than now. Interest rates have never been cheaper. The construction workers who have been idled by the housing slowdown are the very people who would be put to work on transportation related projects. There are spin-offs in related industries—steel, manufacturing, and even mining—and these are jobs that cannot be shifted overseas. If the country is going to borrow and build, now is the time.[See also What Government Needs to Do by Jim Oberstar, former chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee.]

Unfortunately, any consensus on infrastructure financing or a long-term transportation bill won’t be possible until after the election. “It’s fiscally irresponsible and shortsighted,” says Todorovich. “Infrastructure that creates better transportation to move people and goods has economic benefits. There is a clear payback.”

Oddly enough, voters on the local level have been willing to raise taxes for more mass transportation. In the 2010 election, nearly 80 percent of mass transit ballot measures passed. In New York, St. Louis, Denver, and Los Angeles, voters raised taxes on sales transactions, vehicles, and hotel rooms.

Some politicians say the ongoing recession and mounting state and federal deficits make mass transit investment a luxury the country cannot afford, but Smith points out that America has invested in transportation during its most challenging periods—the Transcontinental Railway after the Civil War and the interstate highway system after World War II when the country was deeply in debt.

“And each time America prospered,” Smith says. “It’s no different this time. We will not move this economy forward without investment in reconnecting all of our citizens.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

As a resident of Bloomington-Normal I find the “facts” in this article rather interesting. First, our beloved Mayor is mathematically challenged: It is 165 miles to St. Louis, not 120. It is 130 miles to Chicago, not 150. Next, the building of Uptown Station did not “spur additional investment” as stated. The Children’s Discovery Museum was built several years before the proposal of Uptown Station and the Marriott Hotel also came before this multi-modal transportation center plan came to be.

What the article fails to mention is that somehow we managed to get federal funds to build a transportation center that include a new city hall. In fact, the majority of the building is not transportation related, yet the majority of the funding was the through High Speed Rail dollars. An obvious special thank you needs to go our to US Secretary of Transportation, Illinois’ own Ray LaHood .

July 6 Headline:

California lawmakers approved billions of dollars Friday in construction financing for the initial segment of the nation’s first dedicated high-speed rail line connecting Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Bob- the Tea Party Express left the station, no wait, it never arrived because your party didn’t want to pay for anything towards civic improvement.

This is one of the most idiotic, one sided articles on mass transit out there! Any reasonable, cursory study of the rail project in California would show you a boondoggle and waste of epic proportions.

The Post continues a one sided statist position in selecting their articles. Unfortunately never giving a balanced view. Sad.