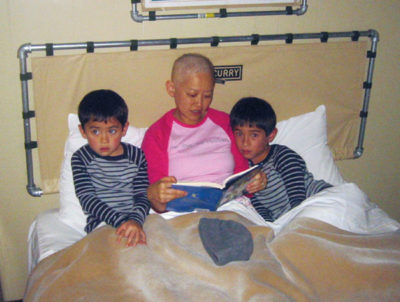

Shortly before my 39th birthday, when I was taking a shower, I felt a lump about the size and shape of a pea in my right breast. I felt a chill go through my body. A week later, on my 39th birthday, I got a biopsy. When the doctor called with the results (I was setting out the birthday cake for my older son’s seventh birthday), the news was bad: I had breast cancer. I wanted to cry, but I couldn’t. It just felt surreal.

In literature and film, medicine is often depicted as a paternalistic profession, with patients given little information and expected to follow their doctors’ orders blindly. In real life, my experience was the opposite. Instead of having an all-knowing doctor telling me what to do, I found myself with a team of doctors relying on me to make the critical treatment decisions. I was like a president with advisors, but I knew nothing about the topics, and the choices and the information were overwhelming. What I expected was Dr. Brilliant Guide; what I got was Dr. Me.

My first appointment was with a pre-eminent breast surgeon at a top-rated comprehensive cancer center. She carefully laid out the options for me: lumpectomy with radiation or mastectomy with reconstruction. The lumpectomy would mean a less invasive procedure and a quicker recovery but also require several weeks of daily radiation and a lifetime of mammograms and MRIs. The mastectomy would entail more invasive surgery and a longer recovery time but eliminate the need for radiation and ongoing screening. Long-term survival odds were the same. My surgeon had no recommendation either way.

Anxious to get her to cast a vote, I tried a personal approach. I had Googled my surgeon before the appointment and found that we were of the same age and ethnicity, and we were both mothers. “You and I could be sisters—twins, even,” I told her. “If you were in my shoes, what would you do?”

She paused before answering. “Whenever women ask me that, I tell them that it’s a personal decision, and that I can’t make it for them,” she said. “But when I look at you, I see myself. I would choose a mastectomy with reconstruction.”

I was grateful for her answer but also frustrated on behalf of other patients. Why do doctors express their much-more-informed opinion so reluctantly?

I had more decisions to make when I met with a plastic surgeon. He laid out the options: saline implant, TRAM flap (which uses skin, fat, and muscle from the belly region to construct a breast), or LAT flap (which uses skin, fat, and muscle from the back region to construct a breast). I chose to get an implant, but I developed severe capsular contracture, which is when scar tissue forms around the implant and causes painful stiffness and hardening of the tissue. After multiple surgeries, I had to remove the implant altogether. In retrospect, I wish I’d considered the choice of no reconstruction at all, but it was not something that I even thought to discuss with the plastic surgeon, nor did he mention it to me.

The hardest phase of my medical training was choosing an oncologist, the person responsible for administering chemotherapy and other systemic cancer treatments. Weeks had passed since my surgery, and I was convinced that the cancer was already beginning to spread. I wanted to begin chemotherapy right away. But the oncologist offered me the most intimidating set of choices yet.

I could take four rounds of Adriamycin plus Cytoxan, either at four-week or three-week intervals. I could add four rounds of Taxol or Taxotere, again at either four- or three-week intervals. I could participate in a clinical trial in which I would receive either a new drug called Herceptin or a placebo. After my chemotherapy ended, I could choose to take five years of an oral hormonal drug called Tamoxifen, or I could suppress my ovaries by taking a drug called Lupron or Zoladex and take five years of an Aromatase Inhibitor such as Letrozole (brand name Femara), Exemestane (Aromasin), or Anastrozole (Arimidex), or I could take five years of Tamoxifen and follow it up with another five years of an Aromatase Inhibitor.

My head was spinning. Having spent an hour describing the options, the oncologist had run out of time and had to move on to her next patient. Rather than recommending a particular course of treatment, the oncologist told me and my husband to go home and think about it and make an appointment to meet with her again.

I didn’t want to wait several more weeks mulling over treatments I didn’t really understand. At my friend’s suggestion, I met with another oncologist. He offered the same options as the first oncologist but recommended a specific course of treatment and gave strong supporting reasons for it. I appreciated that he was advocating an aggressive approach (adding a third chemotherapy agent and combining ovarian suppression with an Aromatase Inhibitor). But, mostly, I was grateful for a straightforward answer. He became my oncologist.

For young women with breast cancer, treatment decisions often extend beyond surgery, radiation therapy, and oncology to medical specialties such as genetic counseling, fertility planning, gynecology, psychiatry, physical therapy, and primary medicine. Unfortunately, even at a comprehensive cancer center, the patient must coordinate these various disciplines. And if you go “a la carte” like I did, mixing and matching doctors in different practice groups and at different hospitals, good luck.

In the end, I had to create an Excel spreadsheet just to keep track of my appointments: breast surgeon every six months; mammogram every year (ideally just before the breast surgeon visit so that we could discuss the results); MRI every year for the first two years (ditto, but scheduled six months from the mammogram); oncologist every four months for the first five years, then every six months thereafter; ditto for the blood test with tumor markers; PET/CT every year for the first three years; bone density test every year for the first five years (to track the bone thinning effects of the Aromatase Inhibitors); MUGA heart scan every few months for the year of Herceptin (owing to the cardio-toxic effects of Herceptin and Adriamycin); gynecologist every six months; primary physician every year; and so on. I was able to keep track of this because I’m fairly organized. But what about most people?

In many respects, the collaborative approach that doctors take to cancer treatment is welcome. No one wants a high-handed doctor making treatment decisions without the patient’s involvement or understanding. But a patient can’t in the end play the role of doctor. We might want to know why a doctor is recommending something; but we still want a recommendation. Also, many of us need a guide just to navigate all the appointments and logistics, which can be Byzantine.

Today, nearly eight years after my initial diagnosis, I continue to be vigilant in monitoring my health. (Hormone-sensitive cancers like mine have a “long tail”—meaning they can recur 10, 15, even 20 years after diagnosis.) I read articles and books about cancer. I attend lectures and take notes about the latest treatments. And I participate in a breast cancer support group.

If, knowing what I know now, I were able to go back in time and advise myself on how to be Dr. Me, I would have said three things that I also say to new acquaintances in similar circumstances. The first is that you should always bring a family member or friend to your appointments and have him or her take notes. Often, we patients are so overwhelmed that we can’t remember what we were just told or don’t ask any questions. The second is that you must take care of your whole self. Treat yourself to delicious and healthful food every day. Watch a funny movie and laugh with your friends. Take naps and hot baths as needed. The third is that you should feel free to complain. I have seen too many friends suffer in silence, whether it’s nausea from chemo (doctors often prescribe the cheapest anti-nausea drugs before moving up to the more powerful stuff) or simply trouble getting an appointment. If the front desk or support staff are unhelpful, tell your doctor—doctors don’t want to lose you as a patient.

In an ideal world, of course, no patient would have to shoulder so many responsibilities along with trying to get well. One of the best improvements that could be made would be for patients with cancer to have a “patient advocate.” If you were diagnosed with cancer, the medical center would partner you with a professional patient advocate who would guide you through the cancer treatment process. The patient advocate would set up appointments for you, make sure your care was coordinated, and offer general health-related suggestions (alternative treatments, massage, nutrition classes, support groups). The advocate might even accompany you to appointments and help you with decision making. This would go a long way toward letting those with serious conditions have the luxury of being patients, so that they don’t have to be Dr. Me.

Ann Kim is the president of Bay Area Young Survivors (BAYS), a support group for young women with breast cancer in the San Francisco Bay area.

Article originally published at Zócalo Public Square (zocalopublicsquare.org).

Help When You Need It

The American Cancer Society (cancer.org) provides helpful information about all types of cancer, and offers amazing programs such as peer support, free wigs and cosmetics, and free transportation to appointments.

For general information about breast cancer, as well as a helpful online community (chat boards), breastcancer.org is a good resource.

Other websites that Ann recommends:

Right Action for Women (rightactionforwomen.org), founded by actress Christina Applegate, educates women about what it means to be at “high risk” for breast cancer and provides aid to those without insurance or the financial flexibility to cover the high costs associated with breast screenings.

Casting for Recovery (castingforrecovery.org) provides an opportunity for women with breast cancer to gather in a natural setting to learn the sport of fly fishing, network, exchange information, and have fun.

Cleaning for a Reason (cleaningforareason.org) partners with maid services to offer free professional house cleaning to women undergoing treatment for any type of cancer.

Little Pink Houses of Hope (littlepinkhousesofhope.org) offers weeklong retreats in North and South Carolina for breast cancer families, providing food, lodging, and activities. Participants provide transportation.

Cancer and career: Many facing cancer have questions about how the disease will affect their jobs. The Disability Rights Legal Center (disabilityrightslegalcenter.org) and Cancer and Careers organization (cancerandcareers.org) are great resources to help with these issues.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is a powerful article and one that I will keep for any future reference, since my Mom had a mastectomy. The note from Lisa also was informative.

Ann, I am glad to know you are doing well. I can completely understand your point of view on this! When a good friend of mine was diagnosed (on THE September 11), she actually brough a circle of friends together, laid out all the options and asked us to vote. While she was not in any way obligated to go with what the group thought, it helped her to remove some of the burden of the entire decision from her shoulders. I thought it was a great example of someone leaning on her friends when she needed it – and allowing us in to help her in such a tough time.