The Blues and the insurance companies represented two of the chief contenders in the field. The third included the so-called independent plans, such as the pioneering Ross-Loos Medical Group in Los Angeles; the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan on the West Coast; the Hospital Insurance Plan, or HIP, in New York; and a number of union plans.

Although all three types offered what were described as highly competitive products to the public, many potential customers found these products about as dissimilar as an automobile, a speedboat, and an airplane. The insurance companies, for example, offered what was clearly insurance, aimed at protecting against costs of hospitalization and surgery. Any individual could buy a policy, provided he could pay the premium and was in reasonably good health or was a member of a suitable group. He could go to any hospital or doctor of his choice. When he was ill, he received benefits in the form of dollars, with which he could pay a portion of his hospital or doctor bill.

At the outset, the Blues offered a program, which was termed insurance in some quarters and prepayment in others. It, too, was intended to soften the blow of the hospital or surgical bill. It was developed originally for people in relatively low-income groups. A patient could go to almost any hospital and doctor of his choice. When he was ill, he received not dollars but actual services, in the form of paid-up hospital or medical care.

With both the indemnity-type policies of the insurance companies and the service-type protection of the Blues, costs were held down by the inclusion of fee schedules, maximum limitations, and similar devices.

In striking contrast, most independent plans offered what is generally known as comprehensive coverage. Costs were higher, but there were relatively few limitations and the patient was usually given complete hospital and medical care as long as his illness required. There was, however, little free choice; the patient was obliged to be treated by a physician working on salary for the plan. This was clearly not insurance against the costs of serious illnesses. It was an attempt to cover the costs of essentially all illness by the technique of budgeting.

Facing three such different programs, many potential customers were somewhat confused and turned to their doctors for advice. They found similar confusion in the medical profession. For at least a brief period, the struggle among the health-insurance groups—especially between Blue Shield and the commercial companies on one side, and the independents on the other—had many of the earmarks of the War Between the States. Medical associations were split asunder. Physicians were stripped of their medical-society memberships and hospital appointments. Individually and collectively, dignified doctors belted one another with oral attacks, lawsuits and even flying fists. They battled in convention halls, hospital corridors, and various tribunals of justice all the way up to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Under ordinary conditions, with gradual growth and development, it is possible that most of the disagreements might have been avoided or at least settled in a more calm and scientific atmosphere. There was no such peaceful solution. From a totally unexpected quarter, a new agency stepped in and proceeded to compound the confusion.

In a series of decisions between 1947 and 1949, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that an employer’s refusal to bargain over a group health-and-accident program for his employees “constitutes an unfair labor practice.”

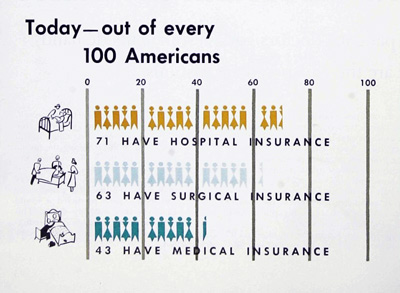

Those decisions meant that health insurance might properly be included in fringe benefits for labor. Accordingly, union leaders walked into wage-negotiation meetings all over the country and demanded health-insurance programs for their members. The effect on health-insurance coverage was astounding. Between 1946 and 1950, hospital-insurance coverage increased by about 80 percent, surgical insurance by 190 percent and medical insurance by 230 percent.

“This dazzling increase has continued almost steadily since 1950,” a medical official said last year. “It has been something to gladden the heart of every salesman. But it has come damn close to wrecking the whole health-insurance program.”

The all-out drive to get more health-insurance customers was marked by more than heightened rivalry among the Blues, the commercial companies and the independents. It was also accompanied by a growing storm of complaints, resentment, and disillusionment.

Much of this animosity was directed at medical leaders themselves, especially at those who claimed that since 60 or 70 percent of the people had “some form” of health insurance, the problem of medical costs had therefore been 60 or 70 percent solved. This kind of arithmetic may have been convincing in some circles, but it proved infuriating in others.

“For example, in 1957, it is true that roughly 70 percent of the people had ‘some form’ of health insurance,” a spokesman for the Health Information Foundation said a few months ago. “But that protection paid only about 30 percent of their personal bills for sickness.”

Many men and women, happily imagining they had nearly complete protection against doctor bills, discovered to their dismay that their policy would pay for only a fraction, and often a small fraction, of their medical bills. Many found their presumed protection did not cover serious illnesses, such as a heart attack or a stroke, when treated outside of a hospital.

Many others found they had protection against big bills rendered by a surgeon, but not against equally big bills rendered by an internist. Many learned that they could not combine adequate protection with free choice of physician—although two recent developments may be changing this situation.

Perhaps the most dangerous resentment was expressed against the rising costs of health insurance. These costs now seem to be going up about 5 percent a year. Oddly, although both the Blues and the commercial companies were boosting prices, public ire was turned particularly against Blue Cross and Blue Shield.

“This is the price of delusion,” claims Prof. Donald MacDonald, of the University of Michigan.

For two decades Blue Cross spokesmen have claimed that their plan is not insurance, but a way to prepay hospital bills. Accordingly, he says, subscribers “do not expect Blue Cross plans to behave like insurance companies.”

Most people expect insurance companies to raise their premium rates when necessary, and to require strict observance of all the contract details. “But many of those same persons become resentful upon learning that their Blue Cross plans employ those practices or propose doing so,” Professor MacDonald declares. “Hence the indignant demands that Government, or labor unions, or someone move to block Blue Cross leaders in such moves.”

Few leaders in any phase of voluntary health insurance view recent increases in insurance costs with any enthusiasm. Moreover, few of them have been able to justify the increases entirely on the basis of rising hospital costs, drug costs, and similar expenses. A large portion, they say, must be charged to abuse of the health-insurance system. In these accusations, blame is heaped equally on patients, doctors, hospitals, labor, and management. The charges range from ignorance, carelessness, and inefficiency to blatant selfishness, money-grabbing, and outright fraud.

To those deeply anxious to make voluntary health insurance succeed, these abuses mean more than a financial threat to any particular program. By influencing the amount and quality of medical care received, and often by determining how quickly that care will be sought, these abuses may endanger the health and even the lives of more than 120 million Americans.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

People unable to leave the hospital for example when they are on IV antibiotics are a common source of over-hospitalization. THey are not released and they are kept against their will in the hospital. And then the insurance company will not pay the stay. They are seen by a battery of doctors they did not solicit sent by the hospital and find themselves with 30,000 to 70,000 of medical debt. I have also seen this when there is a surgical complication for a routine surgery and this is not allowed or noted and the patient is required to stay at the hospital and is not released to go home because of excessive wound care or risk of infection.

It has crossed my mind many times, that Doctors, hospitals and any qualified health providers have the commercial advantage of limited accounts receivables by the portion of their services paid by Uncle Sam through the insurance industry. If I’m wrong, please explain.

Enjoying the articlea(s)