Careful probing of thousands of such replies has shown that occasionally a bookkeeping error or some other simple mistake had been made. But most often the probe revealed cases of “ghost surgery,” unethical fee splitting, atrocious overcharges, and even fictitious services. Perhaps the most shocking disclosure was made by California Physicians’ Service, the Blue Shield plan in California, which found that some 200 doctors in Southern California were bilking their own health insurance program.

The dishonest doctors, spotting what they thought would be an easy way to make a fast dollar here and there, were charging for imaginary house calls, office visits, surgical operations, and postoperative care. “There has been wholesale chiseling by charging for imaginary X-ray and laboratory tests.”

It was revealed that one surgeon sent in a staggering bill for an apparently lifesaving operation performed on a Los Angeles patient. “What staggered us,” said the investigators, “was not only the size of the bill but trying to figure how the surgeon had performed this lifesaving miracle in Los Angeles while the patient happened to be in New York.”

When the offending physicians were trapped, many of them urged medical leaders to handle the situation secretly, “for the good of the medical profession.”

Dr. Wilbur Bailey, the head of the Los Angeles County Medical Association, disagreed. “For the good of the medical profession and for the good of the public, there will be no conspiracy of silence,” he said. “Instead of trying to sweep this mess under the carpet, we’re going to put we’re going to put it right where it belongs—out in the open. The newspapers will be given the facts.”

Although no criminal charges were brought against any of the offending physicians, all of them were forced to make complete restitution. Some, but not all were evicted from their medical societies.

Several medical spokesmen quickly commented that only a relatively few physicians had been apprehended in the California investigation, and that only a mall minority of doctors in the United States could be accused of dishonest practices. Later, the proportion of such men was estimated by AMA officials to be “very small, probably not more than five percent of all medical men.”

Dr. Elmer Hess of Erie, Pennsylvania, a past president of the AMA, declined to take a reassuring view.

“It’s ridiculous to dismiss the problem by saying that perhaps only five percent of our doctors are dishonest,” he told one reporter. “Five percent of the 200,000 docs in the United States—that’s 10,000 men, with incredible power to do harm.”

The vast majority of patients and doctors are decent and honest, the outspoken surgeon declared. “I could run my clinic for five minutes—I wouldn’t even try—if most people weren’t honest. But there are chiselers on both sides, and those chiselers make it necessary for us to set up policing systems.”

Although the cases of scandalous overcharges or outright fraud have attracted most attention, insurance experts claim that such abuses—known frequently as “gouging”—are actually less dangerous in the long run than the practice known as “fudging,” or “creeping costs.”

“Here’s how that works,” says Dr. Norvin Kiefer, chief medical director of Equitable Life. “Take a surgeon who normally charges $150 to $250 for an appendectomy, depending on the income of the patient. For a patient with health insurance, he always charges his top figure—$250. This surgeon is not dishonest, but, whether he knows it or not, he’s sabotaging the whole health-insurance system.”

This fudging has steadily and ominously helped to raise the cost of medical care year after year. The insurance carriers have responded automatically by raising the cost of health insurance. Experienced claim investigators know it goes on, but they are almost powerless to stop it.

“The atrocious overcharge, the gouging—that’s easy to spot,” says one of these investigators. “It stands out like a sore thumb. We refuse to pay, and any medical society will back us up. But the fudging on bills is different. Sure, we can see it, but the doctor tells us—in absolute honesty—that it’s within his usual price range, and we’re licked.”

Another insurance executive says, “A few of those slight increases wouldn’t mean much. But you multiply them by tens or hundreds of thousands of cases a year, and your health insurance would be priced right out of the market.”

In medical circles the justifications for this kind of charging are a matter of brisk controversy. It has been asserted, for example, that a health-insurance policy actually enables the patient to pay more, and that he should logically be charged more. Against this argument, Louis Orsini, of the Health Insurance Association, says, “You can’t logically discriminate between one patient who puts his savings in a bank and another, with the same income, who puts his savings into insurance premiums.”

Many physicians claim they are entitled to extra payment for filling out annoyingly complicated, time-consuming, and apparently nonsensical insurance forms. Insurance officials, while privately admitting that some of the forms could be simplified and improved, retort that these forms are now helping doctors collect an unprecedentedly high proportion of their bills.

In the back rooms of medicine and in the columns of medical journals, an even hotter controversy is currently flaring over the effect of health insurance not merely on the cost of medical care but on the quality of that care.

“This affects more than a patient’s pocketbook,” a Michigan doctor observed last year. “It can affect his life.”

In medical school, he said, doctors were once taught to examine the patient as thoroughly as his condition indicated, and then prescribe only the treatments, which he clearly required.

“But now,” he said, “we first ask, ‘Do you have health insurance?’ If he answers ‘Yes,’ all the rules go out the window and we order the works.”

This all-out attack, with the insurance policy paying the bill, may be highly impressive to the patient. But some physicians are seriously wondering if it is medically sound or even safe.

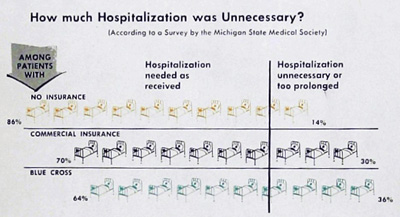

On the theory that “his insurance will cover it,” some physicians are admittedly calling for overwhelming diagnostic dragnets. Even when ordinary examinations clearly point to something as obvious as acute gout, some doctors—including not only young interns and residents but also experienced physicians—often order expensive combinations of X-ray studies, blood tests, urine tests, bacteriological tests and even psychological tests to rule out everything from beriberi and schizophrenia to leprosy and bubonic plague. They are prescribing large and costly dosages of vitamins or other drugs, in the hope that these will not do any damage and may possibly help. In particular, they are calling for hospitalization, which may not be altogether necessary.

This overuse of hospitals, which not only raises the cost of medical care but also requires the construction of more hospitals at the taxpayer’s expense, cannot be blamed entirely on the doctor, claims Dr. Samuel Hadden, president of the Philadelphia County Medical Society.

“Both hospitals and patients bring pressure on the physician,” he says.

Few doctors appear willing to admit that they themselves submit to such pressure from their patients. At a recent Chicago symposium, however, a group of distinguished physicians testified that the pressure exists.

“Not a day goes by that we aren’t being asked by insured patients to do something that we don’t like to do,” an internist stated.

Another said, “There are times when patients say to me that if I won’t do what they want, they’ll go elsewhere. I’m ashamed to admit that I don’t want to lose these patients, and I accede to their wishes even though I know it isn’t good medicine. … But we’re all caught in the same bind.”

According to a third physician, the major problem concerns the patient who claims that “I’ve had my health-insurance policy for three years, and now I’m going to collect on it.” This is the patient, the doctor said, who feels that the insurance company owes him something. He demands every possible kind of medical and hospital care, not because he needs it, but because it won’t cost him any additional money.

“This is the same fellow who wouldn’t dream of burning down his house because he’s paid fire-insurance premiums on it for a few years,” the physician said. “But with health insurance, he feels obligated to collect, even if he has to get himself carved up by a surgeon to do it.”

Still another doctor berated women who insist on going to a hospital, or remaining in a hospital bed longer than medically indicated, simply to have a vacation from upsetting husbands, children, in-laws, and miscellaneous domestic problems.

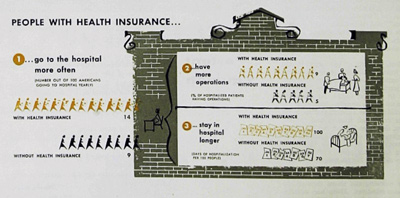

Regardless of who puts pressure on whom, it is clear from numerous studies that people with ordinary health insurance are more likely to go to the hospital, to spend more days in the hospital, and to undergo surgery in the hospital. In a nationwide survey by the authoritative Health Information Foundation, for instance, it was found that 14 percent of insured patients, but only 9 percent of uninsured patients, went to a hospital each year. The typical patient with health insurance spent an average of one day a year in the hospital, as compared to 0.7 of a day for the typical uninsured patient.

While they were in the hospital, approximately 9 percent of the insured patients, but only 5 percent of the uninsured, underwent some form of surgery. The rates for appendicitis operations were 11 per 1,000 for the insured and 5 per 1,000 for the uninsured.

“Although fire insurance does not necessarily increase fires and life insurance does not increase the death rate,” said Dr. Odin W. Anderson, of the Foundation, “the introduction of health insurance is followed by an increase in the utilization of personal health services.”

Whether such an increase is good or bad, he added, “can be endlessly debated.” Some of it undoubtedly represents needed medical services, which might have been impossible without health insurance, but some of it undoubtedly represents overuse and abuse.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now