In the end, America’s great moral issue of the 19th century was settled by a military decision. All the social, economic, and moral questions about slavery ended 150 years ago when President Lincoln considered slaves as part of the Confederacy’s military power and issued his Emancipation Proclamation.

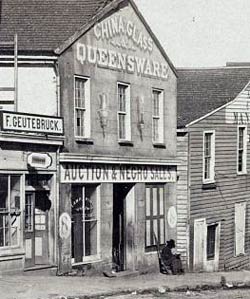

The result, as the Post reported on October 11, 1862, would be profound—militarily, if not morally. The Confederacy was then supporting an army of 225,000 with an enslaved workforce of nearly 3.5 million. Every freed slave would diminish the Confederacy’s economic strength and military resources.

Much as he wanted to end slavery entirely, Lincoln’s first priority was to restore the Union. He told writer Horace Greeley that if he could accomplish that task without freeing a single slave, he would. But the military situation of 1862 brought military and moral needs into a rare alignment.

Even so, Lincoln did not simply act on his own abolitionist principles. He made the proclamation highly conditional. It did not abolish slavery outright, but gave the rebellious states of the Confederacy an ultimatum. They could return to the Union within 100 days and keep their slaves, or else lose them when Federal troops eventually occupied their territory.

In the July 22, 1865, issue of the Post, F. B. Carpenter presented his interview with Lincoln in which the president discussed issuing his proclamation. “Things had gone on from bad to worse,” he said referring to Gen. McClellan’s defeat on the Virginia peninsula that cost 15,000 casualties. “I felt that we had reached the end of our rope on the plan of operations we had been pursuing; that we had about played our last card, and must change our tactics, or lose the game.”

He wrote up the proclamation then read it to his cabinet, not to get their advice but to hear their reactions. No one raised an objection that Lincoln hadn’t already considered until Secretary of State William Henry Seward spoke up. He approved of the proclamation but questioned its timing. Since it would be announced after a string of Union army defeats, it might seem to the public like an act of desperation. “His idea,” said the president, “was that it would be considered our last shriek on the retreat.” Seward told Lincoln to “postpone its issue, until you can give it to the country supported by military success, instead of issuing it, as would be the case now, upon the greatest disasters of the war!”

So Lincoln set it aside and waited. “From time to time I added or changed a line, touching it up here and there, waiting the progress of events. Well, the next news we had was of Pope’s disaster, at Bull Run (and another 10,000 casualties.) Things looked darker than ever.”

On September 13, 1862, he met with a delegation of ministers from Chicago who pleaded with him to abolish slavery. The president said nothing about his proclamation and seemed to argue against emancipation of any kind. “Now, then, tell me, if you please, what possible result of good would follow the issuing of such a proclamation as you desire?”

He wished, he said, to view the matter practically for its advantages in suppressing the Confederacy.

It was true that slavery was essential for powering the South. If he ended slavery, it would weaken the enemy, encourage friends of the union, and draw the support of European powers. But what power did he have? Lincoln asked, repeating arguments he must have posed to himself over and over.

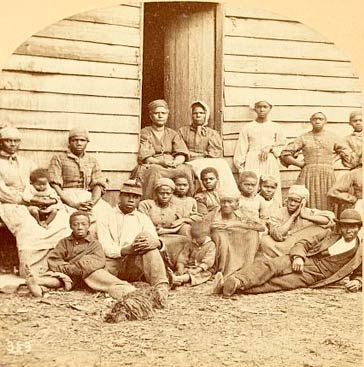

“Would my word free the slaves, when I cannot even enforce the Constitution in the rebel states? Is there a single court, or magistrate, or individual that would be influenced by it there? … And suppose they could be induced by a proclamation of freedom from me to throw themselves upon us, what should we do with them? How can we feed and care for such a multitude?”

He told the delegation that he had received a lot of advice on the slavery issue by religious men.

Some argued for, others against, slavery, but all were certain “that they represent the Divine will. … I hope it will not be irreverent for me to say that if it is probable that God would reveal his will to others, on a point so connected with my duty, it might be supposed he would reveal it directly to me. … It is my earnest desire to know the will of Providence in this matter. And if I can learn what it is I will do it!”

Perhaps Lincoln already knew what the Almighty wanted him to do in this matter. The U.S. Treasury Secretary told Mr. Carpenter that, after the victory at Antietam, Lincoln said the time for the enunciation of the emancipation policy could no longer be delayed. “Public sentiment would sustain it, many of his warmest friends and supporters demanded it—and he had promised his God he would do it!” This last part was uttered in a low tone and apparently heard by no one but Secretary Salmon Portland Chase sitting next to him. He asked the president if he correctly understood him. Mr. Lincoln replied, “I made a solemn vow before God that, if General Lee was driven back from Pennsylvania, I would crown the result by the declaration of freedom to the slaves!”

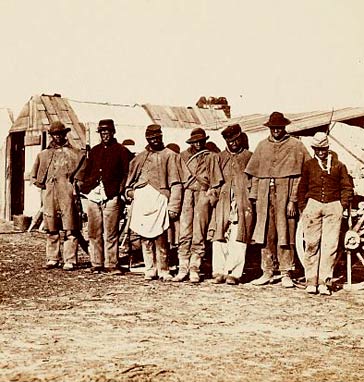

Today, historians question the power of Lincoln’s proclamation. “Did he free the slaves?” they ask, “or did they free themselves?” We now know that most slaves didn’t wait for liberation, but fled from the plantations to the Union lines. There, they set about caring for themselves, finding what work they could in the Union camps, starting farms where possible, and, for many of the men, enlisting in the army.

The liberation of America’s black people couldn’t have occurred without their own initiative. But it also couldn’t have occurred without Lincoln’s decision of September 22, 1862.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This looks like the latest posting from Mr. Nilsson and it is weeks old. I usually come here to read his articles – what happened? Please tell me he’s on vacation and there will be a new article here next week.

President Abraham Lincoln

Has proclaimed that I’m free, I heard,

Called it an emancipation,

A really fancy sounding word.

Some say the word is just a trick

To try to win the Civil War.

Some say that freedom just got sick

Of calling us slaves anymore.

Old times here are not forgotten.

I was, I am, and I will be

A slave in the land of cotton.

No word is gonna set me free.

I’m heading north to make my stand

To live and die in a free land.