Upon investigation I found that in the tangle of red tape at the prefecture of police, the coveted telegram had been shoved under a pile of papers and no one knew anything about it until a long search, instigated at my request, had disclosed the anxiously awaited message. It was a typically Turkish procedure, and just the kind of thing that might have happened at an official bureau anywhere in China. Before Reschad Bey reported to me after his return I had the vessica in my possession and was getting ready to start.

Difficult as was this first step, it was matched in various handicaps by nearly every stage of the actual journey. Again I was to run afoul of Turkish official decree.

In ordinary circumstances, if I had been a Turk I could have boarded a train at Haidar Pasha, which is just across the Bosporus by ferry from Constantinople and the beginning of the Anatolian section of the much-discussed Berlin-to-Bagdad Railway, and gone without change to Angora in approximately twenty-seven hours. It happened, however, that the whole Turkish Army of considerably more than 250,000 men was mobilized beyond Ismid and along the railroad right of way. No alien was permitted to make this journey. Instead of the comparatively easy trip by rail—I say “comparatively” advisedly—he was compelled to go by boat to Mudania, then by rail to Brusa, and subsequently by motor all day across the Anatolian plain to Kara Keuy, where he would pick up the train from Haidar Pasha. Instead of twenty-seven hours, this trip—and it was the one I had to make— took exactly fifty-five hours.

Going to Angora these days is like making an expedition to the heart of China or Africa. In the first place you must carry your own food. There are other preliminaries. One of the most essential, even if it is not the most esthetic, is to secure half a dozen tins of insect powder. The moment you leave Constantinople—and for that matter even while you are within the storied precincts of the great city—you make the acquaintance of endless little visitors of every conceivable kind and bite. Apparently the average Turk has become more or less inured to the inroads of vermin, but even long experience with trench warfare does not cure the European of aversion to it.

It was on a brilliant sunlight Monday morning that I left Constantinople for Angora. Admiral Bristol had placed a submarine chaser in command of Captain T. H. Robbins at my disposal and we were therefore able to dispense with the crowded and none too clean Turkish boat. Accompanied by Lewis Heck, who had been the first American High Commissioner to Turkey after the Armistice, and who now had a business mission at Angora, and the faithful Reschad Bey, I made the journey to Mudania across the Sea of Marmora in four hours, arriving at noon. Until November, 1922, Mudania was merely a spot on the Turkish map. After the Greek debacle, and when the British and Turkish armies had come within a few feet of actual collision at Chanak, and war between the two powers seemed inevitable, General Sir Charles Harington, commander of the British forces in Turkey, and Ismet Pasha—the same Ismet who led the Allied delegates such a merry diplomatic chase at Lausanne—met here and arranged the famous truce that was the prelude to the first Lausanne Conference.

Madame Brotte and Her Hotel

OVERNIGHT the village became famous. The small stone house near the quay where the conference was held is now occupied by a Turkish family and is overrun with children. Instead of making the forty-mile journey to Brusa in the toy train that runs twice a day, we traveled in a brand-new American flivver just acquired by a Brusa dealer, which had been ordered by telegraph and which awaited us at the dock. The hillsides were dark with a mass of olive trees, while in the valleys tobacco and corn grew in abundance. The Anatolian peasant is a thrifty and industrious soul and apparently had got back on the job of reconstruction even while the Greek transports were fading out of sight.

Long before the muezzins sounded from the minarets their musical calls to sunset prayer we arrived in Brusa, the ancient capital of Turkey, and still a place of commercial importance. Here we stopped the night at the Hotel d’Anatolie, where I bade farewell to anything like comfort and convenience until my return there on my way back to Constantinople.

This hotel is one of the famous institutions of Anatolia. It is owned by Madame Brotte, who is no less distinguished than her hostelry. Out in her pleasant garden, where we could listen to the musical flow of a tiny cataract, this quaint old lady, still wearing the white cap of the French peasant, told me her story.

She had been born in Lyons, in France, eighty-four years ago, and came to Anatolia with her father, a silk expert, when she was twenty-one. Brusa is the center of the Turkish silk industry, which was founded and is still largely operated by the French. Madame had married the proprietor of the hotel shortly after her advent, and on his death took over the operation. Wars, retreats and devastations beat about her, but she maintained her serene way. She had lived in Turkey so long that she mixed Turkish words with her French. Listening to her patter in that fragrant environment, and with the memory of the excellent French dinner she had served, made it difficult for me to realize that I was in Anatolia and not in France.

Anatolia, let me add, is bone-dry so far as alcohol is concerned. The one regret that madame expressed was that the Turks sealed up her wine cellar, and only heaven and Angora knew when those seals would be lifted. It is worth mentioning that during the eight days I spent in Anatolia I never saw a drop of liquor. It is about the only place in the world where prohibition seems to prohibit. Constantinople is a different, and later, story.

In Madame Brotte I got another evidence of a curious formula of colonial expansion. When you knock about the world, and especially the outlying places, you discover that certain races follow definite rules when they are implanted in foreign soil. The first thing that the English do is to start a bank. The Spanish invariably build a church, while the French set up a café. So it was in Anatolia.

It was with a certain regret that I bade farewell the next morning to the dear old French dame. In the same flivver that brought us up from Mudania we started on the all-day run to Kara Keuy. At the outskirts of Brusa I saw the first tangible signs of the Greek disaster. Ditched along the roadside were hundreds of motor trucks—unwilling gifts from the Greeks—which the Turks had not even taken the trouble to remove or salvage. As we swung into the open country, ruined farmhouses met the gaze on every side. Whole villages had been wiped out when the Greeks had pressed on for what they had fondly believed to be the capture of Angora. They came back much faster than they advanced.

Travel by Oxcart

We were in the real Anatolia. This mellifluous name, rivaled in beauty of sound only by Mesopotamia, means “the place where the sun rises.” It had long shone on people and events bound up in the narrative of all human and spiritual progress, for we now skirted what might be called the rim of the cradle of mankind. Across these plains had stalked the stately and immortal figures of Biblical days. Here the armies of Alexander and Pompey had camped, and the famous Gordian knot was cut. Here, too, passed the mailed crusaders on the road to Jerusalem, and amid the green hills that rose to the left and right the civilization of the Near East was born.

I now had my first contact with what has been well called the Anatolian oxcart symphony. It is the weirdest perhaps of all sounds, and is emitted from the ungreased wood-wheeled carts drawn by oxen or water buffalo, which provide the only available vehicle for the Turkish farmer. There has been no change in its noise or construction since the days of Saul of Tarsus. It is a violation of etiquette for the driver of one of these carts—the roads are alive with them—to be awake in transit, incredible as this seems when you have heard the frightful noise. He awakes only when the screech stops. Silence is his alarm clock. These carts do about fifteen miles a day. When the Greeks had the important southern Turkish ports bottled up, all of Kemal’s supplies were hauled in these carts for over two hundred miles to Angora.

The farther we traveled, the more did the country take on the aspect of Northern France after the war. Hollyhocks were growing in the shell holes, and there were always the gaunt, stark ruins of a house or village sentineling the landscape. We passed through the village of In Onu, where the Greeks and the Turks had met in bloody battle, and just as the sun was setting we drew up at Kara Keuy, which is merely a railway station flanked by a few of the coffeehouses that you find everywhere in Turkey. A contingent of Turkish troops was encamped nearby. Before we could get coffee we had to submit our papers for examination by the police.

An hour later, the train that had left Haidar Pasha that morning pulled in. We bagged a first-class compartment and started on the final lap to Angora. Midnight found us at Eski-Shehr, once a considerable town, where the Greeks and the Turks were at death grips for months. After the Turkish retirement in 1921 the town was burnt by the Greeks. No sooner was I on the train and trying to get some sleep on the hard seat, for Pullmans are unknown in Turkey, than I began to make the acquaintance of the little travelers who had put the itch into Anatolia. They are the persistent little Nature guides to discomfort.

For hours the country had become more and more rugged. The fertile, lowlands with their fields of waving corn and grateful green were now far behind. As we climbed steadily into the hills we could see occasional flocks of Angora goats. It was a dull, bleak prospect, but every inch of ground, as far as the eye could see, and beyond, had been fought over.

At nine o’clock the next morning we crossed a narrow stream that wound lazily along. Although insignificant in appearance, like most of the other historic rivers, it will be immortalized in Turkish song and tradition. In all the years to come the quaint story-tellers whom you find in the bazaars will recount the epic story of what happened along its rocky banks. This inconsequential-looking river was the famous Sakaria, which marked the high tide of the Greek offensive and the place where Kemal Pasha’s army made its last desperate stand. Very near the point where we crossed, the Greeks were hurled back and their offensive broken. What the Marne means to France and the Piave to Italy, that is the Sakaria to the new Turkey. It marks the spot where rose the star of hope.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

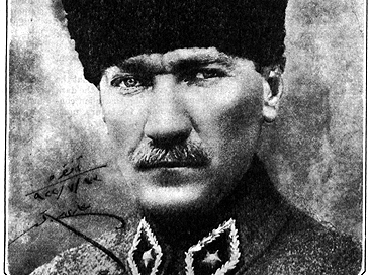

Very clever and very peaceful . Great leader.

History without bias is probably best perceived through articles written at its time for events and personalities which (who) are to be evaluated after passing the test of time, but are tarnished by opponents contemporaneously on purpose because they still continue to effect the present by their lasting resonances. Having learnt him very well to easily admire such a high caliber leader encompassing all universal values at large,I believe Kemal Pasha (our Ataturk) will contine to shine ever more, to become eventually a star above most founding fathers for all humanity.

It was great to read from a amazing journalist who got face to face with the great leader I admire.

Thank you Saturday Evening Post for publishing this article, and giving us another opportunity to learn Ataturk from his own words.

ATATÜRK YÜZYILIN LİDERİDİR. ÖNGÜRELERİ BİR BİR ÇIKIYOR. AYRICA BU RÖPORTAJI GERÇEKLEDİĞİNİZ İÇİN GAZETENİZE ŞÜKRANLARIMI İLETİYORUM…

I really appreciate your help, also publishing online this article is great! Hope many people can reach it easily and read, and understand one more time we had best leader in Turkish history and we need to keep all that improvement in hour life and history.

Thank you one more time for publishing this great article, and many many great years to the Post…

The greatest leader on earth. Thanks for everything Ataturk.

I would like to convey my gratitude to The Post. I have to express my appreciation that among other qualifications, The Saturday Evening Post has the vast experience and capability to enlighten the history.After 89 years posting this interview on your website is great service to acquaint the people on history.

I wish many successful 300 years to Saturday Evenin Post.