No country can win a war if its military strength isn’t matched by the determination of its people. If a war lasts too long, the public’s resolve runs out before the ammunition does. Case in point: it would have been extremely difficult if not impossible for the administration to maintain public support for the Vietnam War for its entire 14 years. More recently, our country’s determination has been challenged by 11 years in Afghanistan that have produced no decisive victories.

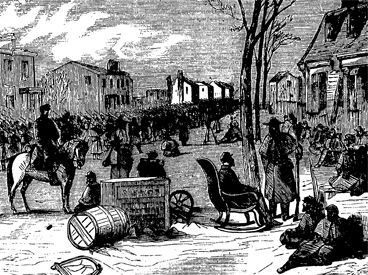

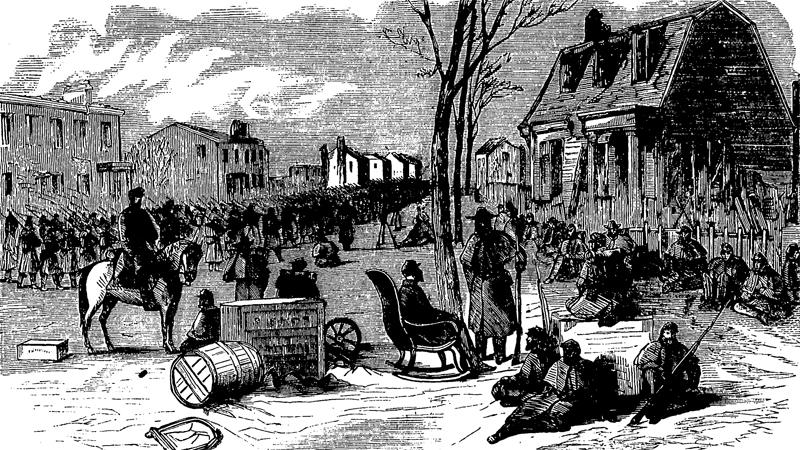

It was no easier 150 years ago, when the Union Army was still recovering from its December 1862 defeat at Fredericksburg. A growing number of Americans were demanding that President Lincoln negotiate with the Confederate government.

In this winter of discontent, the Post responded to the “gloom and dissatisfaction which secessionists are striving to spread over the land” by comparing the achievements of the Northern and Southern armies. In “What We Have Done and What the Rebels Have Done” (February 14, 1863), the editors credited the Union with 33 victories and the Confederacy with just 17.

This ratio of battlefield successes—nearly two-to-one—gives the impression the Union Army was outfighting its Confederate counterpart. But, if truth be told, Post editors were fiddling with the numbers for reasons that were hardly journalistic. The publication had an agenda to stir up waning enthusiasm for Lincoln’s war efforts.

There had been plenty of support for the war when it began in March 1861. Young men throughout the North rushed to enlist, their only worry being the war would be over before they had a chance to prove themselves. After all, they presumed, this would be a short, decisive war.

Then the long list of Union defeats began. In July 1861, the Confederates defeated General McDowell at Bull Run. In March 1862, they defeated General McClellan on the Virginia Peninsula. In August, they defeated General Pope, again at Bull Run. In December, they threw back General Burnsides at the battle of Fredericksburg.

The only place where the Union seemed to advance was in the western states, where Ulysses Grant was making a name for himself with a string of river victories. But Kentucky and Tennessee were a long way from Richmond, Virginia, the seeming invulnerable Confederate capital.

So Post editors rewrote the war to put the Union Army and Navy in a more positive light, using standards that consistently favored the North. For example:

• Three of the Union “victories” were not achieved by combat but reflected territories fell into Federal hands after the Confederates abandoned them.

• The “Evacuation of Manassas” was, in fact, a retreat.

• Two of the Confederates’ major wins at Bull Run were listed as just one victory.

• The editors counted five Union victories in the Peninsula Campaign, but gave the Confederates just one for winning the entire campaign. Moreover, everything the Union gained at Yorktown, Williamsburg, Hanover Courthouse, Fair Oaks, and Malvern Hill, they lost when driven from these battlefields as they retreated down the peninsula.

• Overall, the editors also didn’t weigh the Union and Rebel successes on the same scale: the South’s victories at Bull Run, the Virginia Peninsula, and Fredericksburg were a greater feat of arms than the minor battle of Drainesville or Mill Spring, but reading the Post article, you’d never know that.

Southerners would have recognized the true disparity in the two armies’ successes. They knew that, for all the North’s small victories, the South had kept them from advancing into Virginia for two years. What they couldn’t see in 1863 was how these little victories were quietly adding up and reducing their ability to wage war. The Confederacy still put its faith in winning with a decisive victory in one, big battle. It had been true in Napoleon’s day, but was no longer. Modern wars, waged across the breadth of a nation, were won by countless small wins with little glory and savage fighting.

But a campaign that relies on countless small wins, as we’ve seen in our current fighting in the Middle East, doesn’t look like progress.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now