A grander vision of prison reform would be instituted a few years later at Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary, the fruit of the efforts of the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, founded by a Quaker in 1787. The concept was pure of heart—that the light of God could be discovered in any person, whatever mistakes he may have made in the past. The society preached that prison should be a place of penitence where inmates reflected on their sins. In short, a penitentiary rather than a house of punishment.

When Eastern State finally opened its doors in 1829, the world took notice. Such notables as Charles Dickens and Alexis de Tocqueville came from abroad to tour the facilities. France, Prussia, Brazil, and England, among others, sent representatives. The prison’s design and approach to incarceration would ultimately influence more than 300 prisons worldwide, among them, facilities in China, Mexico, Canada, Czechoslovakia, and Japan—many still active today.

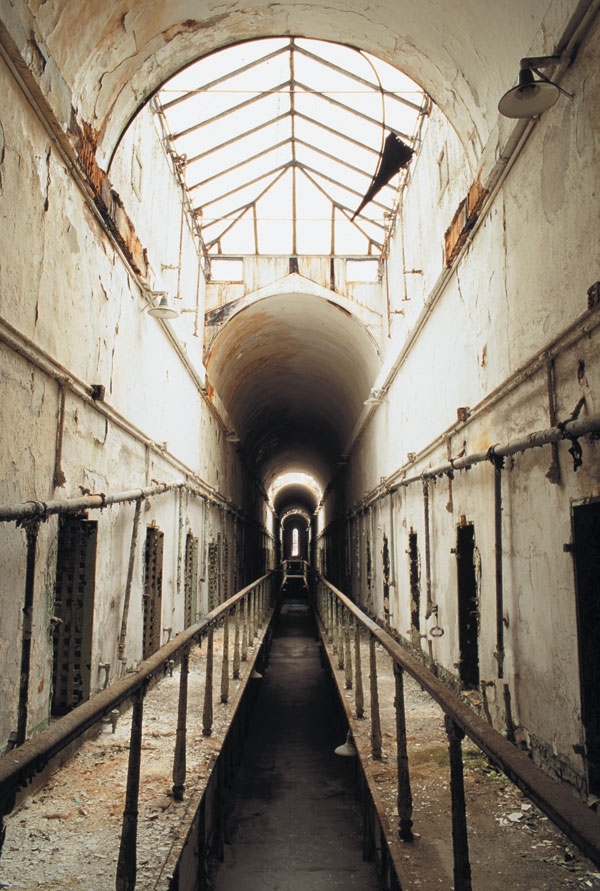

Recently I visited Eastern State, which was closed in 1971 but still stands as a museum. It is an awesome and fearful sight—a testament to the notion that man’s noblest intentions sometimes produce the most dismal results. The walls, 8 feet thick at the base, soar 30 feet high, a stack of soot-stained concrete blocks running for half a mile on each of four sides. The interior was designed to include church-like features, such as barrel-vaulted corridors, pointed-arch windows, and skylights to let in the light of heaven. Each cell was a self-contained unit. Within 18-inch-thick walls, a prisoner had a bed, a desk, a skylight, and a small, adjacent courtyard for the time allowed to exercise. Prisoners had flushing toilets, running water, and central heating, the first time such amenities were included in a building of that size, though the purpose wasn’t creature comfort but isolation.

The isolation was total. Prisoners received no visits from friends or family and reading material was restricted to the Bible. They could work at one of two productive tasks as either shoemakers or weavers.

The cost alone indicates how seriously the prison was regarded: $770,000 spent by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania on construction made it the country’s second most expensive building after the U.S. Capitol. Measured in today’s dollars, it would amount to more than $11.5 billion.

The system, its builders believed, would produce honest men, and supporters argued they were taking a humane and society-improving approach.

In practice, it was a living hell.

In 1841, when Charles Dickens came to see the extraordinary institution, he met Charles Langenheimer, an immigrant incarcerated for theft. Dickens expected to be uplifted by the experience. Instead, as he recounted in American Notes, he was horrified. “There was a German, sentenced to five years’ imprisonment for larceny. … He had painted every inch of the walls and ceiling quite beautifully. He had laid out the few feet of ground, behind, with exquisite neatness, and had made a little bed in the centre, that looked, by-the-bye, like a grave. The taste and ingenuity he had displayed in everything were most extraordinary; and yet a more dejected, heart-broken, wretched creature, it would be difficult to imagine. I never saw such a picture of forlorn affliction and distress of mind. My heart bled for him; and when the tears ran down his cheeks, and he took one of the visitors aside, to ask, with his trembling hands nervously clutching at his coat to detain him, whether there was no hope of his dismal sentence being commuted, the spectacle was really too painful to witness. I never saw or heard of any kind of misery that impressed me more than the wretchedness of this man.”

Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont, reporting back to the French government, interviewed prisoners and also wrote tales of abject misery. “No. 85.—Has been here two months; convicted of theft. Health good, but his mind seems to be very agitated. If you speak of his wife and child he weeps bitterly.”

Other records tell of prisoners banging their heads on walls until they caused open wounds.

“The effects of solitary were brutal,” says Norman Johnston, author of Eastern State Penitentiary: Crucible of Good Intentions. “To be cut off from human contact like that is just horrific.” However, Johnston points out that almost 200 years later prisons really haven’t gotten much better. Johnston says he has been visiting prisons all over the world since the 1950s. “I’m not sure anything works all that well. The new, factory-style supermax prisons are built with efficiency, not rehabilitation or prisoner sanity as a prime objective.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now