J. C. Leyendecker

J. C. Leyendecker

Joseph Christian Leyendecker was born March 23, 1874. Originally from Germany, Leyendecker immigrated with his family to Chicago, Illinois. Early on in Leyendecker’s life he created 60 illustrations for a Bible company, which were published soon after. After completing the illustrations he decided to get formal training at the Chicago Art Institute. He then spent a year at the Academie Julian in Paris with his brother. He returned to Chicago and by May of the same year he had his first piece of artwork on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post. Leyendecker continued to create 322 covers for the magazine over 44 years. During this time he also continued to do advertisements for many clothing manufactures. He also created the iconic Arrow Collar Man using model and possible lover, Charles Beach. He, like many, created recruitment posters during WWI. He and Beach became social icons by hosting lavish parties and his popularity in the art world increased. But as the 1930s came, his popularity faded. His illustrations were no longer used in ads they had been used in for years. Also, when the editor of The Saturday Evening Post was replaced in 1936, Leyendecker rarely got commissioned for covers. He contributed to the war effort, once again, during WWII and soon he was working for The American Weekly designing covers. He died of a heart attack while working on a cover on July 25, 1951. Shortly after his death, Beach and Leyendecker’s sister sold his original Saturday Evening Post covers.

How Americans Saw Themselves in the 1950s

Every time you flip through an old magazine, you open a time capsule. Created to meet readers’ most immediate interests, magazines generally reflect the mood and ideas in brief moments in history.

But how accurate is that reflection?

If you look at Post issues from the 1920s, you can get a fairly good sense of that decade. The overall tone of these issues is busy, enthusiastic, often funny, and the hefty magazines are filled with lighthearted stories and lavish advertising.

The 1930s issues, on the other hand, are much thinner. The Depression-era illustrations and advertising seem subdued and cautious. There are fewer stories and the articles seem to focus mostly on business and politics.

In the issues of the early 1940s, every Post article, ad, and cartoon seems to reflect some aspect of World War II.

The issues of the 1950s, however, don’t quite fit their times. To judge from the images, America was a bright, prosperous, and carefree place, which wasn’t entirely true. The country was prospering, yet it was also weighed down with worries. The decade had begun with two wars: a bloody “police action” in Korea that ended in stalemate and a global cold war that just seemed to go on and on. As if this wasn’t bad enough, Russia had stolen America’s atomic bomb secrets; our great adversary was now a nuclear power.

As the 1950s began, it became to Americans clear they wouldn’t get the peace they’d hope to win at the end of World War II. Instead, they would pass the decade in fear of a Soviet attack with atomic weapons. Air-raid drills would send schoolchildren diving under their desks to wonder if, this time, it wasn’t a drill. Their parents would watch news reports of communist influence spreading across the globe.

They would also have sensed an atmosphere of suspicion and resentment in the country as journalists and politicians accused fellow Americans of disloyalty. Senator Joseph McCarthy would draw national attention for his inquiries into suspected communist agents operating throughout the government. His hunt for secret communists reached its peak 60 years ago this month.

When McCarthy’s relentless attack on the U.S. Army proved too much for his Congressional colleagues, he was censured by his colleagues, and his career–and investigations–faded away. Yet the suspicion of covert communism lingered and many Americans felt they could no longer trust their fellow citizens.

The Post wrote a great deal about the red menace in the 1950s, but if you looked only at the images in the magazine, you’d never guess at the cultural atmosphere of dread, suspicion, and uncertainty.

To judge by the ads below, taken from the May and June issues of the Post, Americans of 1954 were perpetually happy, living colorful, comfortable, and gracious lives. The Westinghouse vacuum cleaner, for example, shows us that icon, the 1950s American housewife. Advertisers and television writers, with no intention of being funny, would present her as homey but glamorous, performing housework in a dress and heels.

She cooked in a modern, spacious kitchen that was filled with modern appliances, such as ‘intelligent’ electric stoves, and spacious refrigerators with rotating shelves.

Modern glamour had even entered the bathroom. Manufacturers introduced exotic colors to fixtures that had, for generations, had only been stark white.

Americans who had moved to the suburbs took pride in their backyards and with summer’s return, the magazine featured advertising from several manufacturers.

The Goodrich ad seems to make unsupported claims in its headlines, but many baby boomers fondly remember those inflatable pools.

With summer, many readers would again consider the merits of a single-room air conditioner, which were become more affordable very year. Several companies were offering units that summer, including Carrier, whose air-conditioners were so advanced, they could prevent “super brain” computers from over-heating.

New technology was invading America’s offices. But no matter how much the machines changed, the gender of the operator remained the same.

No ad gallery of the 1950s would be complete without a collection of car ads. These models capture an era in which the auto industry, as yet unthreatened by imports or emissons standards, focused on power, size, and glamour.

Lastly, we present a gallery of Post coves from those early summer months. Noticeably absent are bomb shelters and students huddled under school room desks.

Like so many of the covers from the 1950s, the art work celebrates intimate, homely moments of small town and suburban family life. We didn’t reflect the country American was in those days. We showed the country as Americans wanted to see it–familiar, peaceful, and contented.

Love at Six

© 2014

Six-year-old Zachary had been in his room all evening.

Mary Ann kept tiptoeing over to her grandson’s quarters in the guest room and pressing her ear to the door. She thought she could hear him crying. “Sweetie,” she said, taking a step back. “Are you okay?” She returned her right ear to the door. Zachary didn’t answer. “Can I come in?” she asked.

Mary Ann loved her grandson, but she couldn’t stand when things got tricky like this. She only got to see him every other month when his mother would drive him up from Vermont, so she felt a little out of sorts when the seas got rough. It was especially hard to do without Tobias around. Her husband had always been better at solving problems.

“Zachary, can I come in?” she called again. “Do you want dinner? Do you want me to read you a bedtime story?” There was no answer. “Didn’t you have a good time today? I thought we had such a good time.”

Finally, she turned the handle and opened the door to the guest room. Zachary had been scared to sleep on the room’s high bed, so she’d piled a bunch of blankets on the floor in front of the fireplace. He was twisted on his side, crying. Next to him was a stuffed animal, an old Rottweiler that was missing his nose. She’d only seen Zachary cry once before when he’d fallen from a tree in her daughter’s backyard, but these tears, she thought, had nothing to do with physical discomfort.

In time, she managed to lower herself to the ground and curl up next to Zachary. He didn’t budge, but he took her hand and rubbed it. The meeting of two such things—young and old skin—made her happy. “Did you have a good day today?” she asked. “Are you okay?”

“Kind of,” Zachary said. He twisted his head and lined his gaze with Mary Ann’s. His eyes were glassy and tears had left the tops of his cheeks shiny.

“What do you mean ‘kind of’?” she asked. “Ever since you got off the phone with your mom you’ve been quiet. Then you came in here and didn’t even have supper. The grilled cheese I made you is cold, and the tomato bisque looks ugly.”

“I’m sorry, Grandma,” he said, flopping onto his back and shutting his eyes. His lids pushed out the remaining tears and he erased them with his knuckles.

“It’s all right. I can make you another one if you feel like it. The first one wasn’t that good anyway. Maybe I can do better.”

She’d gotten along without Tobias these past seven years and was proud of that, but sometimes having a person in the house made it hard. Taking care of someone else reminded her of taking care of Tobias, bringing him soup in bed and scanning his back for bedsores. She missed him so much that it was best she didn’t think of him and how happy he’d made her. It’d been years since someone had kissed her goodnight and whispered “I love you,” and it seemed like the words were on the verge of extinction.

“What happened on the phone with your mother? Did you tell her how much fun we had at the lighthouse? How we may have seen a shark? I think it was a shark, don’t you? Wasn’t it great up there? Up so high? And we were so lucky that the nice man was there, and that he opened up the stairs and led us up to the top. You know, I’ve been there maybe twenty times, but never to the top. You have to be someone special to go up there. Maybe they saw you and that’s why they allowed it.”

Zachary laughed. Mary Ann continued to stroke his fingers.

“It was a perfect day,” he admitted. “I love the lighthouse. I really do. It’s so tall, and I love that it’s painted like a candy cane. Why do they make them like that? Is it so ships can see them from far away?”

“I don’t know. They’re not always striped. We should have asked the park ranger. He would’ve known. Are you warm enough? Do you have enough blankets? Are you homesick? Do you want to go home? You know, tomorrow it’s supposed to be another beautiful day and we can go to the botanical gardens and feed the ducks. I’ve got some stale bread that they really like.”

“Why don’t we buy them good bread?”

“I hear they like stale bread better,” she cajoled.

“Really?”

Mary Ann nodded. She moved her hand to his belly and patted his soft flesh. She didn’t see her daughter in Zachary, but she could hear her—the curiosity and innocence. “Do you want me to put on a fire for you, like last night?”

“Yes, please.”

“It wasn’t too hot?”

“It was hot, but I liked the sound, and I didn’t need a nightlight because the flames were so big.”

Rarely did she make a fire these days, even when the Maine winters were harsh. Tobias had installed the best heating system, so she just pressed the lever to the right when the temperature dropped. Still, she knew that all heat wasn’t created equal, and that a fire was still king, especially in the eyes of child.

Zachary and his mother lived in an apartment in Montpelier, and it didn’t have a fireplace. Last night, when she’d gotten up to get a glass of water, she’d peeked into the guest bedroom and spotted Zachary–sitting up ‘Indian style,’ she thought they called it—a few feet from the fire, mesmerized by it. Plus, she thought it probably did the chimney good. It was seldom used even when Tobias was alive, and she thought the flames’ flickers erased the bricks’ long-lasting chill.

She went to get more wood for the fire, and as she piled it in a heap, she turned back and glanced at Zachary. He was smiling now, and his eyes were bright and clear. “So,” Mary Ann said, “what happened on the phone with your mother?”

“I told her that I want to work in a lighthouse when I grow up,” he said.

“Oh, Sweetie, that’s wonderful!” She piled on more wood and pulled a few sheets of newspaper from the adjacent basket. The funnies were dusty and over four years old. She jammed them underneath the grate, struck a match, and then had Zachary bring the fire to the cartoons. “You’re so aware and bright—you’ll make sure nothing happens to those ships.”

“She said it can’t happen,” he pouted. “That all lighthouses are now automatic or something.”

“Is that true?”

“I guess.”

“And that’s what made you sad?” Mary Ann returned to Zachary and they both sat, staring at the fire, studying the flames as they bent and twisted through the wood.

“Yes. I was so excited. I knew what I wanted to do with my life and where I wanted to live and how it was all gonna be, and then my stupid mom ruined it all,” he said as the tears began to well in his eyes again.

“Honey, it’s okay. Shhh.” Mary Ann scratched his back.

“I was gonna live in Maine and have a dog–a big dog–maybe a St. Bernard with one of those little barrels around his neck,” he explained as he cried some more. There was little build up with his tears, Mary Ann thought. They went from zero to sobbing in moments. “And then. And then…” he trailed off.

Mary Ann draped a quilt over her grandson’s shoulders. “And then?” she asked. “And then what?”

“And then my mom told me about you,” he mumbled sadly.

Mary Ann pressed her tongue against the roof of her mouth. “Oh, dear,” she said. “What about me? Did I do something wrong? If I did, Zachary, I’m deeply sorry. I really am.”

She worried that their visits would be spaced out even farther now, and that instead of meeting every other month, they would be every three or four months. In time, Zachary may not want to make the trek up the interstate to spend the weekend with her at all.

He spoke so softly she couldn’t quite hear him.

“What was that?” Mary Ann asked.

“I said,” he said, shaking the quilt from his back, “that I wanted to live in the lighthouse and be with my dog—the St. Bernard—and that I wanted to marry you, but she told me that I couldn’t marry you. That you only marry people you love. And then I told her that I loved you more than any other girl and she told me that that is a different kind of love. Is it true?”

Mary Ann paused. She looked at Zachary and brushed some of the straight hair from his face, tucking it behind his ears. She swiped her fingers below his eyes to rub out the remaining droplets of tears. Smoke built up in the chimney and the fire began to catch, popping and crackling.

“It’s true,” she finally said, “but it’s a better kind of love–one that’s sure to last forever.”

Zachary nodded, inched closer to his grandmother, and then nuzzled his face against her left arm. She kissed the top of his head, drew in his warm scent, and watched the blaze wrap the dry pine.

The Leopold and Loeb Murder Trial, 90 years later

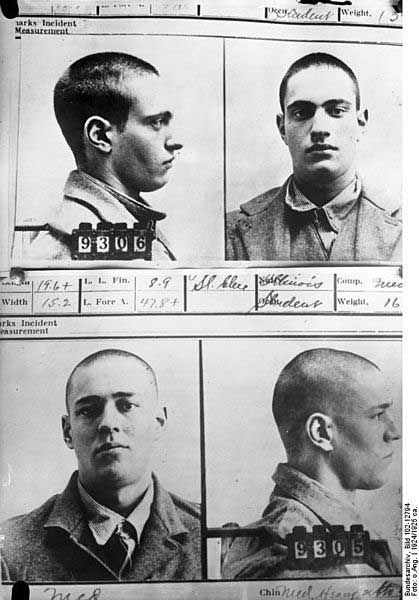

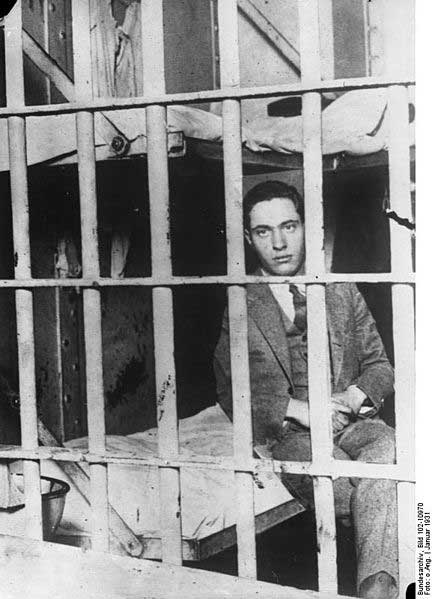

Source: German Federal Archives, Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-00652 / CC-BY-SA

The recent news of a bungled execution has again stirred debate over capital punishment, emotions running high between advocates and opponents of state executions.

So it is interesting that this week marks the 90th anniversary of a horrific crime and a defense that, remarkably, spared the lives of two killers. If any criminals were worthy candidates for execution, they would have been Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb.

In 1924, they pled guilty in a Chicago courtroom for a crime with a shocking motive. The two teenagers—wealthy and highly intelligent—had murdered a fourteen-year-old boy to prove their ability to live beyond traditional ideas of good and evil and to demonstrate their intellectual superiority.

They began with petty crimes in 1923: theft, arson, and vandalism, but then set their sights on committing the perfect crime.

On May 21, 1924, Leopold and Loeb rented a car and drove to a school in the Kenwood area of Chicago, where they would find their intended victim: Robert Franks. Loeb was able to convince the boy to get into the car with them because Franks was his cousin, and he had played tennis at the Loeb house often.

With the boy inside, the car sped off. The moment the car turned the corner, one of the young men—it could never be established whether it was Loeb or Leopold—dragged Franks into the back seat and killed him by repeated blows to the head with a chisel.

The young men wrapped the boy’s body in a robe and drove south to the Illinois/Indiana border. Their destination was Wolf Lake, a stretch of open industrial land beyond the Chicago limits where Leopold had frequently gone bird-watching. There, they dumped the body in a railroad culvert and returned home. That night, Leopold called Bobby Franks’ mother to tell her that her son had been kidnapped. The next day, they mailed a ransom demand, which had been written on a stolen typewriter.

Even before any ransom could be delivered, however, a worker discovered the body of young Franks. Leopold and Loeb decided to abandon the kidnapping, a ruse only intended to distract the police. They destroyed the typewriter and the robe they had used to wrapped the body, and then went on with their lives, convinced that the crime would never be traced back to them.

Leopold simply ignored the outcry in the newspapers, but Loeb couldn’t stay away from the investigation. He followed the police and reporters covering the case, and struck up conversations with them so he could offer some misleading theories about the crime.

While searching the area where the body had been discovered, a detective found a pair of glasses with a unique hinge design. He learned that only three pairs of glasses such as these had been sold in Chicago, one of them to Nathan Leopold. When questioned, Leopold told the police that, as an avid birdwatcher, he often visited the marshes around Wolf Lake, and that he must have dropped the glasses in the marsh on a similar expedition.

Source: German Federal Archives, Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-12794 / CC-BY-SA

The police now treated Leopold and his friend Loeb as suspects. When they were brought in for questioning, both young men claimed they spent the night in the family car, cruising around Chicago, looking for girls. But the Leopold family chauffeur later told police he had been working on the family car all that night.

Confronted with this inconsistency, Leopold broke down and confessed. Loeb soon admitted his guilt as well.

The trial that followed grabbed headlines across the country. Loeb’s family, fearing their son would be executed for the murder, hired Clarence Darrow, the famous defense attorney and well known opponent of capital punishment.

Following Darrow’s orders, the young men pled guilty to the charge, which meant they would be tried without a jury. Darrow believed he could get leniency more easily from the judge than from a jury.

With the question of guilt answered, America’s newspapers now focused on the question of whether or not Leopold and Loeb would hang.

As the trial closed, Darrow summed up his defense before the judge in an argument that ran for 12 hours. He made the usual argument that capital punishment did not prevent other crimes. Murderers simply did not think of being caught and executed at the moment they killed.

He asked the judge to consider the age of the defendants: Leopold was 19 and Loeb, 18. He added that hanging the young men would also mean a life-long sentence of bereavement for their families.

But in his summing up, Darrow addressed the larger issue of public vengeance and disrespect for life. From time to time, he said, a blood hunger had risen up in society. When Americans were consumed with a desire to punish others or defend themselves, they would “place a cheap value on human life.”

He had seen it in 1917, when the country had been consumed with war fever. Young men were encouraged to see killing as a solution. “The tales of death were in their homes, their playgrounds, their schools; they were in the newspapers that they read; it was a part of the common frenzy—what was a life?” he asked. “It was nothing. It was the least sacred thing in existence and these boys were trained to this cruelty.”

After the war, he argued, the homicide rates had risen. A generation had grown inured to killing, often seeing it as a solution to problems.

America, Darrow argued, needed to return to the level of civilization it had enjoyed before it contracted war fever. “More and more fathers and mothers, the humane, the kind and the hopeful… ask that the shedding of blood be stopped, and that the normal feelings of man resume their sway… I am pleading that we overcome cruelty with kindness and hatred with love.”

Source: German Federal Archives, Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-10970 / CC-BY-SA

“I know the future is on my side,” Darrow said. “Your Honor stands between the past and the future. You may hang these boys; you may hang them by the neck until they are dead. But in doing it you will turn your face toward the past.”

In the end, the judge sentenced both Leopold and Loeb to life imprisonment plus 99 years for the kidnapping.

It is interesting to note that Darrow did not argue that Leopold or Loeb would reform if spared a death sentence. He knew they were “not fit” to be loose in society. “I believe they will not be, until they pass through the next stage of life, at forty-five or fifty,” he admitted. “Whether they will then, I cannot tell…”

“When life and age have changed their bodies, as they do, and have changed their emotions, as they do—that they may once more return to life. I would be the last person on earth to close the door of hope to any human being that lives, and least of all to my clients. But what have they to look forward to? Nothing.”

Loeb was killed by an inmate after twelve years in prison, but Leopold lived long enough to be paroled and was released in 1958, having serving 33 years. He had kept his sanity by teaching classes for other inmates, learning over two dozen languages, organizing libraries in the prison, and participating in medical research.

Upon his release, he moved to Puerto Rico where he had been hired by the Church of the Brethren. For the remaining 11 years of his life, he worked among the poor as a hospital technician.

He had often been asked in prison if he had reformed. As a Post article reported in 1955, he would reply that he was “quite a different person today. Even physically there is not a cell in my body that was there in 1924.”

Despite all the years that had passed since his vicious crime, he still could not understand or explain his own actions. The Post quoted him as saying,

“I am in no different positions today than I was twenty-nine years ago. I can’t give you a motive that makes sense. It was just a damn-fool stunt done by a child, a child without any judgment. It seems absurd to me today, as it must to you and all other people. I am in no better position today to give you a motive than I was then.”

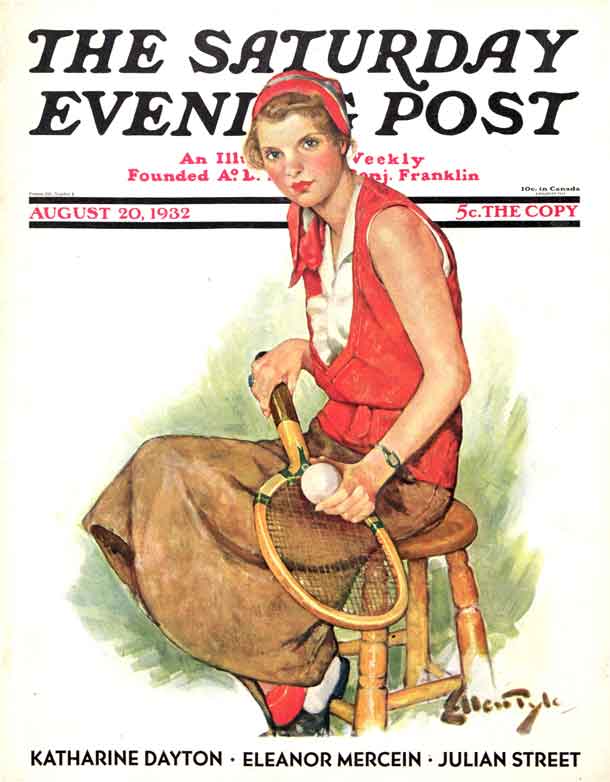

Beyond the Canvas: Flapper-era glamour fades as The Great Depression looms

August 22, 1932.

© SEPS 2014

Ellen Bernard Thompson Pyle’s early illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post idealized the 1920s era of glamorous parties and celebration in much the same way Norman Rockwell would later celebrate an idealized rural America of the 1940s and 1950s.

But her notorious depictions of confident flappers in short dresses and even shorter haircuts changed when The Great Depression hit America in October of 1929. Pyle’s color palette and composition took on a darker tone that reflected the nation’s mood.

Pyle’s illustrations from the 1920s and 1930s show women competing in activities like archery, swimming, tennis, gardening, and hockey. The paintings are joyous and playful in the 1920s but become reserved in the 1930s.

Pyle’s August 20, 1932 cover, “The American Girl,” is a perfect example of the change in tone. Where Pyle once showed women smiling in brightly colored outfits, fashionable haircuts, and make-up, this Depression-era cover shows a female tennis player in a muted, brown canvas skirt and a loosely-hanging red top, her hair pulled back by a handkerchief. The glow of her cheeks results from the effort of her workout; it is not the rosy blush of joviality.

Not only has the color and hubris drained from the painting, but Pyle also foregoes her 20s era props of luxurious cars and carriages. This woman just sits on a simple wooden stool. Unlike her carefree flapper predecessor, the American girl of the 1930s is now a resilient heroine who adapts to tougher circumstances. She does without.

The darker color palette of browns and deep reds, combined with the wood of the racket and stool, project an air of simplicity as opposed to the gaudy glam of the decade prior. Rather than show an idealized world of parties that the majority of Americans would never know, Pyle turned to a sense of realism that would better connect with the struggles many Post readers were facing during the Great Depression.

To learn more about Ellen Pyle and to see other inside illustrations and covers from this artist, click here!.

To learn more about Ellen Pyle and to see other inside illustrations and covers from this artist, click here!.Beyond the Canvas: Late Night Snack

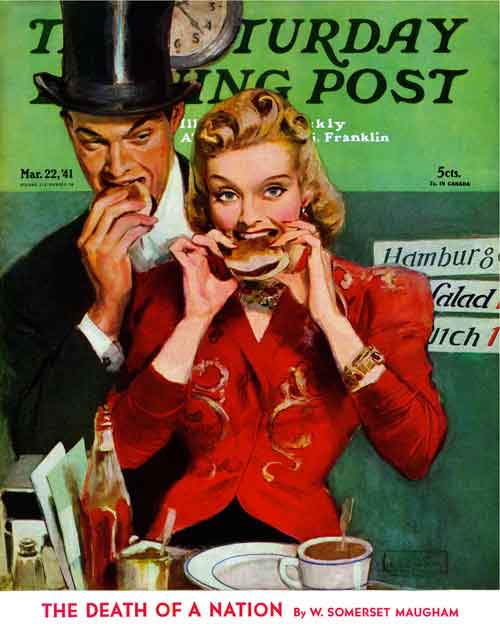

March 22,1941.

© SEPS 2014

John LaGatta was an artist known to blend the glamour, extravagance, and sensual atmosphere of 1920s haute couture with the realistic scenes of American life. His March 22, 1941 cover for The Saturday Evening Post does just that. “Late Night Snack” keeps the high-class party going into the wee hours of the morning at a simple American diner.

Unlike the quiet, demure insomniacs of Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, LaGatta shows two partygoers out of their element, enjoying the remnants of their fun-filled night in a low-key restaurant at 2:23a.m. (depending on how one reads the clock’s thick brushstrokes).

One wouldn’t think the tails-and-top-hats crowd would so eagerly enjoy a late-night hamburger and cup of coffee at a local dive, but all that drinking and dancing can work up anyone’s appetite.

At the tail end of The Great Depression, the bubble of Gatsby-esque extravagance had long since burst. The average American of the 1940s might not grab a late night bite in gala attire, but people still got dolled up for events; dates that might’ve ended with a post-midnight snack in the neighborhood burger shack.

Thus, The Saturday Evening Post readership–and all Americans really–can relate to this cover on realistic terms while at the same time romanticizing the glamour of the party they imagine the subjects have just left. It’s relatable even if the painting idealizes the unfamiliar, like a never-ending, “old Hollywood”-era affair.

The woman in the painting eats with some sense of unfamiliarity, a mix of not wanting to ruin her lipstick and maybe not knowing how to properly eat a hamburger. Her fashionable sleeves are rolled up, showing how ready she is to bite into this American classic.

The work’s color scheme is highly contrasted to make the scene pop with activity. The reds of her jacket and fingernails, along with the ketchup bottle, draw the eyes to the center of the painting and cause the moment of taking a bite to jump off the page.

The gentleman’s eyebrows raise in anticipation of her reaction, as do her own. This may be the couples’ first time getting a burger together, so they’ll make sure to savor the as yet untested American treat.

LaGatta does a magnificent job of mixing his famous, extravagant style with down-home Americana. He painted many covers for the Post, all including beautiful, graceful women. His depictions were never explicitly sexual. Rather, they were as some critics have called them, “frank admirations of beauty.”

To learn more about John LaGatta and to see other inside illustrations and covers from this artist, click here!.

To learn more about John LaGatta and to see other inside illustrations and covers from this artist, click here!.Hush, Now

© 2014

My grandfather, a fiercely private man, born in the nineteenth century, could never have imagined his personal life would be posted and available to any yahoo out there for thirty-two dollars a month. I guess at this point he has moved on.

During an innocent search on one of those genealogy websites, an unknown relative appeared. I was only wanting to see my ancestry line like the celebrities on that TV show. Really, I was hoping to find a connection to the Salem witch trials. No witches so far, but I hadn’t finished looking. I know they are out there somewhere. The trouble was, I found an unknown uncle. On my mother’s side. Again. Seems her father had another family she found out about after his death. As an only child, she was thrilled to find her half-sisters still living on the East Coast, odd elderly spinsters, but sisters nonetheless.

The website glaringly exposed my grandfather’s previous wife and listed my mother’s half-sibs with their birth dates neatly typed on the form. No big surprises. I recall seeing the old copy of our family tree with a thick, black band of ink drawn over the previous wife. Ah, those were the days when an inch or two of white-out could solve a multitude of problems.

My only memory of my Grandpa Walter is sitting together on a big, covered porch in Dayton, Ohio. I was about six. I was putting stamps into a child’s stamp book, and he was breathing. He gazed down at the small, green valley in front of us. White horses grazed peacefully. I don’t remember talking to him due to the lung machine the size of a refrigerator he was attached to. Occasionally, he would take the mask off and enjoy a pipeful of sweet cherry tobacco, which I can still smell sometimes. At the age of six, I saw nothing wrong with this and neither did he.

I was conjuring up that rich, tobacco smell when a tantalizing little icon swirled up on the screen asking me if I wanted to see something else. Well, do ya? It seemed a little condescending. Only a middle-aged woman in her newly empty nest would go this far anyhow. The last of my three kids had recently left for college in a blur of loud music and hair straighteners. I really had to find something better to do than plot our family tree. It was that TV show that started the whole thing.

Without hesitation, I clicked the mysterious icon and waited patiently while the screen produced a copy of an old, hand-written record of people and their households in a 1919 census. In tidy, cursive handwriting that you don’t see anymore, my grandfather’s name was listed, along with a wife, Sophia. Sophia. What an exotic name after weeks of looking at Ebenezers and, I kid you not, Ichabods. “Swine Flu” was scrawled under the “died” section for poor Sophia. My heart sank. I had just met her. The date was a few years before his marriage to a second wife, my grandmother coming in a distant third.

I was so excited to discover this wonderful tidbit that I almost missed the sweetest thing of all. A baby. Baby Walter. Another half-sib for my mother. I never thought of these people as related to me. My first thought was to call her. Then it occurred to me that maybe all of these “surprises” were becoming difficult for Mom. My second thought was, he could still be alive.

Feeling like Nancy Drew herself, I entered the baby’s name in a search. A matching result came up so quickly there wasn’t even time to bite my fingernails. There it was, Walter Z. Burroughs, born 1918, Salem, Mass. I broke the news to my Yorkshire Terrier, who showed overwhelming enthusiasm, wagging and panting at the discovery. Now what?

I went to the online white pages and there he was again, 93 years old, from Massachusetts, living in Tacoma, Washington. Tacoma! Really! Not thirty minutes away from my home? What a strange coincidence. With a shaky hand, I wrote down the address and phone number. The site indicated that it was a nursing home in an area I was not familiar with.

When my husband came home that evening I bombarded him with my news. “I have an uncle.” Since both of my parents were supposedly only children, my family tree is an extremely tall, thin one–a towering pine, perhaps. My husband’s is more like family groundcover, so I don’t think he could possibly feel my excitement at this discovery.

“Call him,” he said casually as he stabbed a scalloped potato. I don’t know if he even likes scalloped potatoes. It was the kids’ favorite.

“Is it a good idea to call a 93 year old man and rock his world at this point?” I pondered. I pictured my frail grandfather withering away at the end of his oxygen tube like the last tomato on an October vine.

“I say call him. He’s your uncle, after all. Good dinner, by the way.” He wiped his mouth, gave me a quick smile, and headed for the garage to work on his never-ending wood project. Soon, the sander growled in the distance while I cleared our few dishes off the table.

I thought about calling my daughter, Chloe, at college to see what she recommended, but I knew her answer would be, “Go, go meet this man now!” Which was not a bad idea. He may not be around much longer. I decided I would call her after I did this brave and outgoing thing.

The next morning was a Tuesday, as good as any. I kissed my husband good-bye and rinsed out the coffee press. Walter’s phone number sat on the counter. I wiped down the stove top and then started pulling things out of the refrigerator to be tossed. Enough, I thought, holding a half-empty jar of sauerkraut. “I’m being a wimp,” I told the dog. He heard, “Do you want a cookie?” and started bouncing maniacally up the cabinets toward his treat bag. It was enough encouragement for me.

I picked up the phone, gave the dog a cookie, and quickly dialed the number. It rang once, and I hoped I would get an answering machine to at least try out my voice.

“Sunset Nursing Home. May I help you?” asked a deep, female voice rough with the sound of years of hard work (and maybe a few cigarettes).

“Yes, I am trying to reach Walter Burroughs.” I curled my hair with my fingers, a nervous habit I haven’t done in twenty years.

“Certainly.” The voice sounded curious. “May I tell him who’s calling?”

“OK. My name is Jan Wilmitsky, but he won’t know me.”

“Just one minute, dear.”

I waited while big band music played in my ear. I pictured Walter, in a black suit, with a silver cane, seated in an elegant concert hall enjoying the music when an usher taps his shoulder to inform him of my interrupting call. Instead, another female voice, this one softer, came over the line. “This is Dolly.”

My heart pounded in my chest. “Oh, hello. This is Jan Wilmitsky. I’m trying to reach Walter Burroughs.” He must have refused to leave the concert hall.

“I’m Mr. Burroughs’ nurse. He’s sleeping now. Can I take a message?”

I was afraid of sounding like a crazy person. These women seemed a little protective of my precious uncle.

“Oh, yes, sure. Like I said, my name is Jan Wilmitsky.”

“Got it.”

“And I believe I may be Mr. Burroughs’ niece.”

“Really?” The nurse sounded optimistic but quite cautious.

“It shows in the records I have recently uncovered that he is my uncle from his father’s side. I would like to come and talk to him if that’s possible.” I hated how my voice rose up at the end like a question. He was possibly family after all. I lowered my voice, kind of like Oprah’s, and gave her my phone number.

“I’ll give him the message,” Dolly said in a professional manner.

By the following afternoon I had received a phone call back from Dolly and had a meeting arranged for four o’clock the next day. Old people have to move fast. No time to waste. Four o’clock, tea time. Yes, he was definitely one of us.

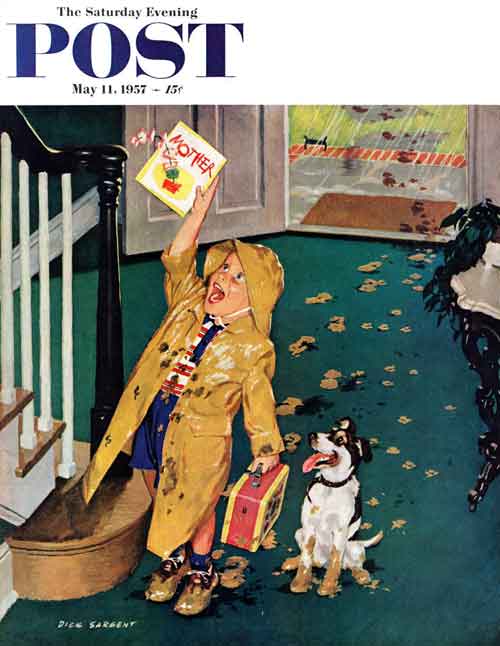

Beyond the Canvas: Muddy Mother’s Day

May 11, 1957. © SEPS 2014

As illustrator Richard “Dick” Sargent once said, when it comes to children, “expect the unexpected.” On his May 11, 1957 cover for The Saturday Evening Postc, “Happy Mother’s Day,” we see a jubilant young man enter the family home with gifts for his mother: a Mother’s Day card, a muddy-pawed pooch, and a muddied front hall.

The perspective of the cover illustration is tilted off-center to give us the impression of being taller than the subject, the same view as an adult looking down on a child. The boy’s broad smile and call up the stairs tell the viewer he’s entirely ignorant of his heinous mud-tracking crime. In his excitement to impress his mother with a gift, he’s forgotten to take off his galoshes.

This funny, relatable situational comedy has happened to American families a million times over. Children are filled with impulse, an innocence of excitement that gets in the way of all other thoughts. Even for those of us who have never had children, we have all been children and can understand this moment. Bursting to share our joy or discoveries, we forget (despite a million admonitions) to take off our shoes once inside, tracking mud and other undesirables through Mom’s clean house. It’s adorable irony that this boy’s excitement over giving his mother a homemade card, which he likely hopes will make her day, has inadvertently given her more hassle than happiness.

This may even be a true story that happened to the artist. Sargent loved children, and he enjoyed illustrating scenes from his own life. He often used his own mischievous, redheaded son, Anthony, as a model. In fact, Anthony appears here as our muddy little man. Perhaps this was Sargent’s perspective one day as he came around the corner to check out the commotion in the front hall.

In the end, Sargent’s simple scene of a rainy May Mother’s day shows that even poor weather cannot deter the happiness and excitement of a loving child. Although the floor is muddied, the child’s intentions never were.

To learn more about Richard “Dick” Sargent and to see other inside illustrations and covers from this artist, click here!

To learn more about Richard “Dick” Sargent and to see other inside illustrations and covers from this artist, click here!America’s First Superstar: William Cody (AKA Buffalo Bill) and his Wild West

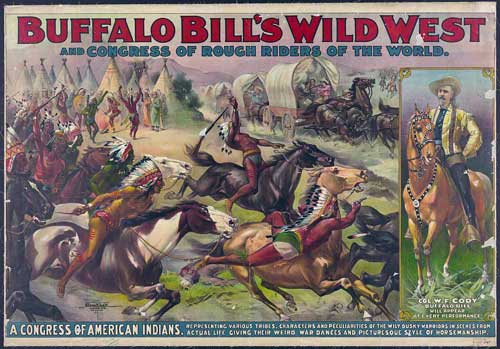

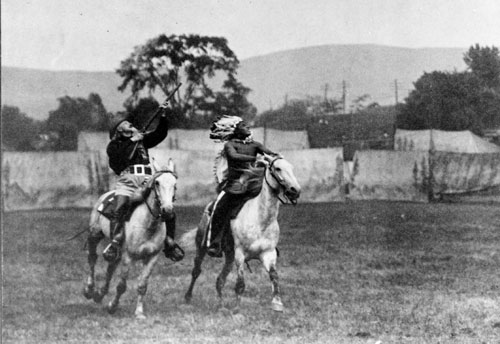

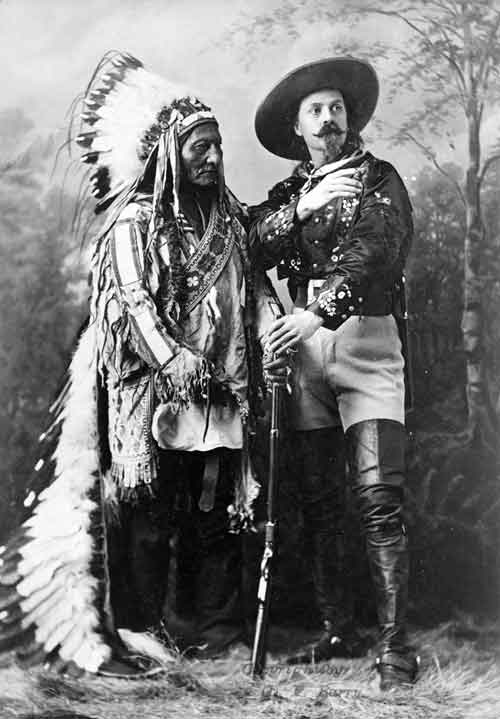

There had never been a celebrity like him. At the height of his popularity, William F. Cody was probably the most recognized man on earth. He received the adulation normally reserved for kings and presidents. And he became the idol of a generation through thousands of appearances in his own extravaganza: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World.

The show was as unique as the man. Far more than a circus or rodeo, his 1,000-member troupe featured exhibitions by talented riders and marksmen of the west. A typical show would include trick riding and races between cowboys as well as Native Americans. One of the big stars was the diminutive (4’11”) Annie Oakley who, shooting at a distance of 30 paces, could split playing cards edge-wise, hit dimes tossed in the air, or knock a cigarette from the lips of her husband.

The show also included western melodramas that mixed historical fact and fiction, like the re-enactment of Custer’s last stand, in which a regiment of cowboys dressed as soldiers were defeated by Indian riders. After the last man has fallen, Cody and his men would ride onto the scene too late to save Custer or his men. Next came the re-enactment of Cody’s shooting and scalping of the Cheyenne warrior Yellow Hand—a true occurrence—which was presented as his revenge for Custer. The final number was an attack by Native American horsemen on the cabin of a pioneer family. In this case, Buffalo Bill and his men arrived in time to drive off the Indians and save the white settlers.

Source: Library of Congress

The secret to the show’s remarkable success and long run—from 1883 to 1906—was Cody himself. He was more than a skilled marksman and horseman, he was the real thing—a true hero of the old west.

At the age of 11, he was working as a rider for a wagon train. Over the years, he found work as buffalo hunter, pony-express rider, trapper, prospector, and Army scout (which is how he earned the Medal of Honor).

In 1869, he came to the public’s attention when writer Ned Buntline made him the hero of one of his dime novels Buffalo Bill, The King of the Border Men. The book became a successful play. When Buntline wrote a second Cody play, Scout of the West, Cody agreed to play the lead, and for the next ten years, he appeared before the public as a theatrical version of himself.

During this time years, it appears Cody tried to copy Buntline’s success by writing a novel of his own. Prairie Prince, The Boy Outlaw; or, Trailed to His Doom, appeared in our October 16, 1875 issue.

The story opens with a young woman…

“A maiden upon whose sunny head but fifteen summer suns have shone.” She is wandering the prairie, stalked by a pair of hungry wolves. She is saved at the last minute by “a mere lad… tall in stature, well formed, with broad, square shoulders, small waist, and limbs of which an Apollo might well have been proud, while his every movement was graceful” etc.

When the young lady’s father, Major Racine, asks the identity of his daughter’s rescuer, an orderly says, “It is the Prairie Prince, sir.”

“No!” exclaims the Major. “Can this be that daring boy whose wonderful deeds have gone along the whole border, and have gained him the name of the Prairie Prince?” And Major Racine gazed with a strange interest into the boy’s face, while the soldiers crowded around and bent upon him looks of admiration and respect. Quietly, and with a proud smile upon his lip, the youth sat his horse, his clear, piercing eyes meeting the gaze of the military commander” etc.

The authorship is debatable. “Prairie Prince” might have been Cody’s own novel, or something Ned Buntline wrote under Cody’s name. If it was Cody’s work, he was smart not to make writing his future.

Source: Library of Congress

After a decade of playing someone else’s version of Buffalo Bill, Cody decided to present his own version of the character. On May 1, 1883, he premiered his Wild West show, appearing with a troupe of veteran cowhands and Indian riders from the Sioux tribe.

Up to that time, much of America’s entertainment was based on European styles and traditions. But Cody introduced the country to something wholly American. It was new, exciting, and home-grown.

A year after the Wild West opened, Cody received a letter from Mark Twain who praised the show–“It brought vividly back the breezy wild life of the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains, and stirred me like a war-song”–and encouraged Cody to take his “purely and distinctively American” show to Europe.

Three years later, Cody followed Twain’s advice. The Wild West troupe arrived in Great Britain in time for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. Over the next four months, over 2.5 million Britons watched Cody’s spectacle and formed a general impression of Americans from this extraordinary showman.

He wasn’t a bad representative of his countrymen. He was well-mannered, good-looking, and could skillfully handle a gun and a horse. And he was highly representative of Americans in his attitude toward the modern age. He regarded the past with a conflicted, sentimental perspective; he liked progress but hated the cost. He celebrated the white settlement of the west but regretted what it had destroyed.

His ambivalence can be seen in “Hunting Down the Buffalo,” which he wrote for the Post on July 15, 1899. “As late as 1869, General Sherman reported nine million buffaloes on the prairies, and this was a conservative estimate. Ten years later these vast herds were completely wiped out—a whole division of the animal kingdom stung to death by the bullets of wasteful professional hunters, who left millions of pounds of fine meat rotting in the sun.”

He assured Post readers that the slaughter was necessary: “It was a sharp, quick way of ridding the plains of a cumbrance that had to give place to a wiser use of these fine grazing lands. It was another instance of civilization getting what it wanted and never minding the cost.” It is a curious attitude for a man who earned his reputation and nickname for killing buffalo.

In the article, he drew a parallel between the fate of the buffalo and the Native American. “We could not make useful citizens of the Indian, and we could not run our brands on the buffalo, so now there are few Indians and no buffaloes.” Both, he believed, had fallen victim to the greed of white settlers.

His audience might not have shared this conclusion, but they were applauding it when they watched his show. His fair-minded attitude was part of the appeal of the Wild West. Like most superstars, his success came from an ability to see a little farther down the road than his audience.