1965: The Birth Control Revolution

It would be hard to define the precise beginning of the sexual revolution in the United States. Some believe it started in 1960, when the FDA approved the use of oral contraceptives, popularly called “the pill.” Presumably, the availability of a reliable, convenient birth-control method started a widespread shift away from traditional attitudes toward sex, relationships, and women’s rights.

But you could make the case that it didn’t really start until five years later, when the Supreme Court handed down its decision in Griswold v. Connecticut. The result of that decision made distribution of birth control pills or devices, and the dissemination of birth-control information, legal in all 50 states.

Prior to the 1965 ruling, it was technically illegal in many states to distribute contraceptives or even information about birth control. These laws were a legacy of the 1800s, when a national movement to improve public morals led to statutes that branded birth control materials as “obscene and immoral.”

Connecticut had some of the most stringent laws banning birth control. Anyone found guilty of distributing or using contraceptives could be sentenced to a year in jail. By 1965, however, the law was often overlooked. The state didn’t prosecute doctors in private clinics who provided contraceptives to married women. But the law could still be applied to doctors at public clinics.

In 1961, Estelle Griswold, the executive director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut, challenged the law. She opened a birth control clinic in New Haven, and was soon arrested, tried, convicted, and fined. She appealed her case to the Supreme Court, which handed down a landmark decision in 1965.

In Griswold, the Court ruled that people had a constitutional “right to marital privacy,” which was violated when state laws prohibited the use of “any drug, medicinal article, or instrument for the purpose of preventing conception.”

Within days of the Griswold decision, several states changed their laws, despite a hue and cry from some quarters that access to the pill would encourage promiscuity. New York removed all restrictions to birth-control information and contraceptive sales to anyone over the age of 16. Massachusetts followed, then Ohio and Minnesota. Seven other states went so far as to encourage family-planning services.

It should be noted that Griswold only applied to married couples. It would be another seven years before the Court extended the same right to contraceptives to unmarried couples.

Within months of the decision, The Saturday Evening Post published an article by Steven M. Spencer (below) that, in hindsight, brilliantly framed the impact of the Court’s decision. He wrote that legalized birth control was producing a “revolution” that was “transforming laws and love in America.”

THE BIRTH CONTROL REVOLUTION

Originally published on January 15, 1966

By Steven M. Spencer

Photos by Bill Binzen

Barriers fell in the year just ended, and birth control became a national policy. Here is how the ‘pill’ and the ‘loop’ are transforming laws and love in America and offering women new freedom and new responsibilities.

“Oh, I know I’ve put on a little weight since I started on the pill,” said a Chicago housewife in her late 20s, “but I think it’s just from contentment. I used to worry a lot about having another baby, and that kept me thinner, but I never have to worry anymore. We have three children, from three years to six months, but with two still in diapers I’d prefer to wait for the next until the youngest is at least two years old. And now I know I can wait.” This young mother is typical of the millions of American women who today are leading a new kind of life, for they have gained what for eons was denied the daughters of Eve—a secure means of planning the birth of their children. They are the beneficiaries of one of the most dramatic sociomedical revolutions the world has ever known.

The revolutionaries are the small band of determined men and women who for more than half a century have promoted planned parenthood. Scorned and despised at first, they gradually caught up doctors and lawmakers, millionaires and presidents in their endeavor, until their goals be-came socially acceptable and almost the entire nation changed its mind.

The implements of the revolution are “the pill” — the oral contraceptive tablet the woman of 1966 takes 20 days of each month — and the increasingly popular intra-uterine device, a coil or loop of plastic or metal worn in the womb for as long as a woman wishes to avoid pregnancy. With the pill and the loop, in spite of possible side effects and rare hazards, the science of birth control has now reached a degree of effectiveness and convenience undreamed of even a decade ago.

These technical advances, combined with a growing concern about the world population crisis, brought the birth-control revolution to a historic turning point in the year just closed, for 1965 marked the fall of most of the last important barriers against general distribution of family-planning information and services.

It was the year that the U.S. Supreme Court threw out as an unconstitutional violation of privacy the 86-year-old Connecticut law that had forbidden the use of contraceptives and forced the closing of birth-control clinics.

Positive legislative steps were taken in 10 other states, including New York.

It was the year the Federal Government, taking its cue from President Johnson, became more directly involved in birth-control activities than ever before. Early in the year the President had pledged he would seek new ways “to help deal with the explosion in world population,” a problem he rated second in importance only to achieving peace. In his June address to the United Nations he urged that we “act on the fact that less than five dollars invested in population control is worth $100 invested in economic growth.” Appropriately, as the year closed, the Ford Foundation announced it was granting $14.5 million for research on human reproduction and fertility control. “Only birth control on a massive scale,” Gen. William Draper Jr., national chairman of the Population Crisis Committee, said in December, the day after the Ford Foundation announcement, “coupled with rapidly increased food production in the developing countries, can prevent the greatest catastrophe of modern times.”

As Draper spoke, the Ecumenical Council of the Roman Catholic Church was drafting a text on birth control. The traditional foe of all contraceptive techniques except periodic abstinence, the church during the past several years was shaken from parish to Papacy by disagreement and debate on the topic. Many Catholic couples, including the estimated 35 percent in America who use methods not approved by their church, hoped the Ecumenical Council would modify the ban, but no such change was forthcoming. According to some observers, however, including Dr. John T. Noonan Jr., an American professor of law at Notre Dame University who is a consultant to the Pope’s commission on marriage problems, the council’s final document lays the groundwork for eventual change. If so, 1965 will indeed be remembered as a revolutionary turning point.

One cannot be sure that the birth-control revolution will move fast enough for the nations to avert the starvation and overcrowding of runaway population growth. Hundreds of millions of human beings are already on the brink of famine. Recently a special panel for the White House Conference on International Cooperation declared that “the rate of growth of world population is so great — and its consequences so grave — that this may be the last generation which has the opportunity to cope with the problem on the basis of free choice.” But although the effect of the birth-control revolution upon the nations remains in doubt, there is no question that it will have an enormous impact upon marriage in America and the American family. Birth-control advocates speak of a strengthening of love between husband and wife once the fear of unwanted pregnancy disappears from sexual relations; they predict an easing of family financial strain and warmer relationships between parents and children as other stresses are removed. Already many of the five million American women taking the pill are enjoying at least partial relief from the menstrual tensions and pains that have always been considered their inescapable lot. Scientists are perfecting an injection that not only prevents conception but suppresses menstruation for months. This and other prospective developments reported here‑including a “morning-after” pill-promise the American woman, already the freest in the world, still vaster freedom.

The freedom, however, extends not only to wives but to unmarried girls, and the choices that the latter make can mean a widening of the rift between the generations. There are indications that a majority of unmarried young women still observe the standards of sexual behavior taught by their parents or their religion. But many seek in sexual activity the confirmation of their “identity” as free adults, and, whether by legitimate or underground routes, the pill has found its way to the college campuses and even to the high-school hallways. Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone, an eminent planned-parenthood expert, tells of an encounter with a girl in a New York City junior high school during a break between classes. The girl had dropped her handbag in the crowded corridor, and its contents spilled on the floor. “I stopped to help her pick the things up,” Doctor Calderone said, “and was astonished to see a package of birth-control pills. I asked the child, ‘Do you really know about these things?” ‘Oh, yes,’ she replied, ‘I take them every Saturday night when I go on a date.’ She had gotten the pills from her married sister — apparently without benefit of instructions. If it weren’t so funny, it would be tragic.” In fact, it probably will be tragic. One pill alone is quite ineffective. They must be taken daily for five to seven days before any protection is built up.

Many of birth control’s most ardent supporters candidly admit that the new freedom provided by the better methods carries with it — as does any freedom — corresponding dangers. While for the first time in history men and women have the ability to make an absolute and free choice as to the purpose and result of their sexual actions, good choices still require intelligence. “We now have the means of separating our sexual and our reproductive lives,” says Doctor Calderone, “and we have a great responsibility to make proper use of both of them.”

II THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION

In her efforts to control the number and spacing of her children, woman down through the centuries has resorted to many recipes, often more strange than effective. She was advised in an Egyptian papyrus of 1500 BC to use a concoction of acacia tips, bitter cucumber and dates, mixed with honey. Dioscorides, the famous Greek medical scientist of the first century, prescribed willow leaves in water (willow because it was thought to have no seeds) or the leaves of barrenwort finely ground and taken in wine. Other Greek medical writers offered a choice of powerful amulets, including one made of henbane seed diluted in mare’s milk and carried around the neck in a piece of stag’s skin.The woman of today takes nothing more exotic than a pink pill (or a white or peach-colored one). Or she wears a small device within the womb, a hidden amulet, so to speak. Although these intra-uterine devices are fast gaining acceptance in foreign countries, they are far less used than are the pills. In addition to the five million American women taking the pills on doctors’ prescriptions, there are some 2.5 million abroad, mostly in Latin America, Europe and Australia. And the market continues to expand.

Not since the sulfa tablets emerged in the 1930’s to conquer pneumonia and a host of other infections, has a little tablet exerted such far-reaching influence upon the world’s people. It may, in fact, be the most popular pill since aspirin. It is certainly relieving bigger headaches—both family and global. And all at a cost of about $1.75 for a month’s supply. The pill is big business, produced by seven firms, advertised in the medical journals in two- and three-page spreads with lace-and-roses borders and sold in “feminine and fashionable” dispensers. Some resemble powder compacts, others, telephone dials, marked off to help the woman keep track of the days she should take them.

From the very outset the pill’s ability to prevent ovulation, and therefore pregnancy, has been virtually 100 percent when taken faithfully as directed. This is usually for 20 days beginning with the fifth day of menstruation. Only total abstinence or surgical sterilization can equal or surpass their record. When pregnancies have occurred, it has been because the woman was unknowingly pregnant before she started taking pills, or because she forgot them for one or more days.

The “mother” of the pill is Mrs. Margaret Sanger, the famous founder of the birth-control movement in America who today at 87 is living in Tucson, Ariz. Physically infirm, she is still sharp of mind and can look back on a half century of hard-won achievements and a life struggle marked by arrests, jailings, and verbal abuse. Many years ago Mrs. Sanger recognized the limitations of the principal methods offered by the birth-control clinics — diaphragms and spermicidal jellies — and she suggested to Dr. Gregory Pincus of the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology, in Massachusetts, that he try to develop something better.

“Then one day in 1951,” Doctor Pincus recalls, “Mrs. Sanger approached me again. She was especially disappointed by the failure of conventional methods in India. She said, ‘Gregory, can’t you devise some sort of pill for this purpose?’ I said I’d try.” With a grant of $2,500 from Mrs. Sanger’s Planned Parenthood Federation, he and his associates went to work on it.

Pincus was not starting blind. Scientists had known since 1900 the fundamental bodily chemistry that the birth-control pill exploits. They knew that chemicals called hormones, secreted by a woman’s pituitary gland, cause her ovary to release a ripened egg each month-the process is called ovulation. They also knew that if the egg becomes fertilized and attaches itself to the lining of her uterus (the beginning of pregnancy), still another hormone cancels out the pituitary hormones and prevents ovulation, keeping her ovary from secreting more eggs during the nine months that the fertilized egg is growing into an infant. It was this anti-ovulation hormone, identified in 1934 as progesterone, that Doctor Pincus sought to imitate in an oral birth-control tablet.

Researchers at the University of Rochester had used progesterone in 1937 to prevent ovulation in rabbits, but efforts to apply the rabbit findings to humans had been discouraging until Doctor Pincus and his associate, Dr. Min Chueh Chang, took up the problem. Dr. John Rock, then clinical professor of gynecology at Harvard, independently tackled the same problem, and soon he and Pincus’s group joined forces.

As director of the Reproductive Study Center in Brookline, Doctor Rock was originally trying to induce ovulation in women unable to have babies. Pincus and Chang were seeking an oral method of preventing ovulation. By a curious physiological paradox, both goals were achieved, in differing degrees, with the same hormones. When Doctor Rock gave progesterone and another sex hormone, estrogen, to 80 previously infertile women daily for three months, and then stopped, 13 of the women became pregnant within the next four months, apparently because the hormones had improved the condition of the uterus and tubes. This became known as the “Rock rebound effect.” At almost the same time the Pincus-Rock team demonstrated the value of the hormones in preventing ovulation, when taken for 20 days.

But since the natural hormones had to be given in large oral doses or by painful injections, Doctor Pincus’ group sought a more convenient synthetic substitute. They screened some 200 chemical relatives of progesterone and found three that looked promising. The first medical use of the synthetic hormones was in the treatment of menstrual irregularities. Then, in December 1954, Doctor Rock began administering them as a contraceptive to a group of women in Brookline. In April 1956, large-scale tests began in Puerto Rico and later in Haiti and a number of United States cities.

At first the Food and Drug Administration approved the pills for only two years of continuous use. But under careful observation by research doctors, many women continued them without harm for much longer periods. Some have taken them for as long as 10 years, and certain of the pills are now approved for four years of use. When women have stopped the pills to have a baby, there has been no impairment of their fertility.

Tests over the years have shown that the amount of hormone in each pill need not be as large as originally believed. On the principle that the less hormone you take the better, so long as the effect is achieved, manufacturers have steadily reduced the concentration. One company’s pill, which began as a 10-milligram tablet several years ago, is now down to 2.5 milligrams, and a new one-milligram tablet may soon be introduced to the market. In addition to the pill’s clear superiority in effectiveness, women like its neatness and its complete dissociation from the sexual act. “I simply take a pill every evening,” one young suburban mother remarked, “and, my God, it’s wonderful not to have to worry.” Another plus for the pill is that it has brought into the birth-control clinics thousands of women who would not otherwise have come, or who, discouraged by less easy and reliable methods, would have dropped out. Dr. Richard Frank, medical director of the Planned Parenthood affiliate in Chicago, says that up through 1961 not more than 30 or 40 percent of the women stayed with the methods then offered-usually the diaphragm. But a recent count showed that 75 percent of those introduced to the pills were still using them after several years.

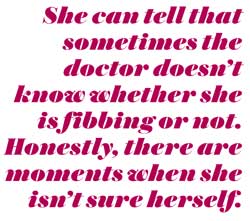

No one claims, in spite of the generally favorable experience, that the pill is perfect. There are side effects, most of which resemble the familiar symptoms of early pregnancy — nausea, some swelling and tenderness of the breasts, headache or fatigue. There is often some weight gain and occasional “spotting” during the month. But only a small minority of women experience the side effects — figures range from 2 to 15 percent, depending on the specific symptom. The problems tend to disappear after the first two or three months, especially with the newer low-concentration pills. And if one variety of pill is troublesome, the doctor may prescribe another. Although weight gain is a frequent complaint, doctors believe it may be only a physical reflection of the pill’s psychological benefits — the freedom from worry that it brings to many women.

Of graver concern are the still unsettled questions about whether or not, in rare instances, the pills produce serious illnesses. Cancer, for example, has caused moments of alarm. Here a key point is the difference between causing a new cancer and stimulating the growth of an already existing one. The estrogen component of the pills is believed capable of causing the enlargement of an existing cancer of the breast or pelvic area, and if the doctor suspects such a malignancy, he will not prescribe the pills. “For this reason it is important for women taking the pills to have periodic breast and pelvic examinations,” says Dr. Robert W. Kistner, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Harvard.” “I think that they should be examined as often as every six months.”

There is absolutely no evidence, however, that the oral contraceptives will initiate cancer. Early uneasiness on this point was stirred up by research on inbred strains of laboratory rats already prone to breast cancer. Careful analysis of the medical histories of thousands of women on the pills has revealed nothing to indicate the pills can produce a cancer that was not already there.

As a matter of fact, there is now well-founded opinion that the pills may actually prevent cancer of the uterus. Doctor Pincus and his associates discovered a definitely lower rate of positive “Pap smears” among women taking the pills in Haiti and Puerto Rico. And at Harvard Doctor Kistner was able to protect rats from the known cancer-inducing effect of certain chemicals by feeding them contraceptive pills. “It may well be that cancer of the uterus is a preventable disease,” he says.

Another illness that some have linked to birth-control pills is thrombophlebitis. This is an inflammatory and sometimes fatal clotting in the veins. A number of cases, and a few deaths, have been re-ported among women taking the pills, in both the United States and England. The reports have received wide publicity, but the cause-and-effect relationship has been clouded by the fact that thrombophlebitis has always been rather common among women of childbearing age, the very group now taking the pill. Among millions on the pill is would not be surprising if a few women coincidentally suffered from blood-clotting complications. The verdict at present: neither proven nor unproven. But to be safe the Food and Drug Administration requires the manufacturers to advise the doctors not to prescribe the pills for women with a history of thrombophlebitis, pulmonary embolism, stroke, or liver disease.

Just last November the FDA added one more precautionary note, a warning to watch for any blurring or loss of vision among women on the pill. Here again, the cause-and-effect has not been established, as the FDA points out. But a Johns Hopkins eye specialist, noting a few suspicious cases of eye trouble and other neurological complications, asked for reports from other doctors and received 73. Many of the women affected had histories of high blood pressure or other conditions that might have accounted for the eye symptoms.

For women who have medical difficulty with the pill, the answer may be the intrauterine devices, particularly the Lippes loop, named for its designer, Dr. Jack Lippes of Buffalo, N.Y. Originally hailed mainly as a method for those who couldn’t afford the pills or who were too ignorant to count the days, the intra-uterine devices (IUDs) are now gaining favor among wealthy women on Park Avenue and in fashionable suburbs.

“Members of some of our most prominent families have been using IUDs for as long as three years,” a New York obstetrician revealed, “and are very well satisfied.” A Boston doctor had to install a second telephone to help handle calls from women wanting IUDs. More than 200,000 women in the U.S. have been fitted with them.

Family-planning experts have repeatedly emphasized that the effectiveness of any method depends to a large extent on the motivation of the woman, or the couple. To have a free choice is one thing. To exercise it through deliberate decisions is another. With the pill, the need to make the decision is at least removed in time from the moments of rushing passion. But as Dr. Sheldon J. Segal of the Population Council points out, “Once a woman has the IUD successfully installed, she makes her next decision only when she wants to have a baby; then she goes to her doctor and has the device removed.”

The loop, coil or bow is soft and elastic enough to be squeezed into a hollow plastic tube for insertion into the uterus, where it springs back into its original shape. To avoid infection or accidental perforation of the uterine wall (which has occurred a few times), the device must be inserted with care by a physician, preferably one with some training in gynecology. Most doctors insert the IUD for a reasonable fee—that for a regular office visit. But some have charged as high as $100, $200 or even $400, reports a New York obstetrician who has been speaking out against such exorbitant prices. Last September the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists cracked down on the high-fee practice and suggested in its news-letter that the charge be “not in excess of $25.” The devices themselves, as sold to the doctors, range in price from $1 for the loop to $1.80 for the steel ring, with a small additional charge for the instruments needed for insertion and removal. In large quantities, for use in clinics, the cost is only a few cents apiece.

No one is yet certain just how the intra-uterine device interferes with conception. The currently favored theory is based on meticulous research carried out at the University of California at Los Angeles. Investigators there, after artificially inducing ovulation in monkeys and then artificially inseminating them, found that the IUD causes the egg to hurry down the Fallopian tubes before it is mature enough to be fertilized.

Doctors do not usually advise IUDs for women who have never had a baby. The devices have the added disadvantage that only about 75 percent of women who do try them find them acceptable. An estimated 15 percent must have them removed because of pain, excessive bleeding or other medical reasons, and 10 percent accidentally expel them, sometimes without knowing it. But about 97 percent of those who can retain the IUD are protected against pregnancy, a lower score than the pill’s but still better than that of older methods.

Even with its imperfections the IUD is regarded as one of the most practical methods of coping with the world-population crisis. The Population Council, supported mainly by Rockefeller and Ford money, has sponsored extensive worldwide trials, focusing especially on India, Taiwan and Korea. India, now launched on a $400 million birth-control program, has received 1.2 million IUDs from the Population Council. And last summer it started a factory to turn out 14,000 loops a day, distributing small gold-plated loops as souvenirs of the opening-day ceremonies.

In the IUD and the pill, the birth-control revolution has formidable weapons against the world-population explosion. The science of birth control, however, is pushing on toward new techniques that may make birth control even easier. Several drug companies, for example, are developing an injection that will prevent ovulation for one to three months, depending on the formula. One compound produces its effect so gradually yet so powerfully that a single shot will suppress both ovulation and menstruation for six months to a year.

The injectables are still in the trial stage and won’t be on the market until completion of tests on more than 5,000 women in several states, but preliminary reports are promising. Menstruation occurs normally with the once-a-month injection, as it does with the daily pills. But it can be suppressed by the longer-acting injectables or by taking certain types of contraceptive pills through the full month, without interruption. Dr. Charles Flowers, professor of obstetrics at the University of North Carolina, finds that women suffering from painful or excessive menses, or from the irritability and “witchiness” of premenstrual tension, are delighted to be relieved of these troubles for several months at a time.

But the injection is just the beginning. Among the new advances promised for the future is a vaccine against pregnancy, now being worked on by several groups. One approach involves extracts from the egg and the sperm. Dr. Albert Tyler of the California Institute of Technology has found that a sperm extract injected into the female rabbit will coat the rabbit ova so that a live sperm from the male rabbit cannot attach itself to fertilize the egg. Anti-conception vaccines suitable for human use have not yet been perfected, however. Doctor Tyler, though optimistic about the future, points out that such vaccines “must not make wives allergic to their husbands.”

Such allergic tragedies would be avoided by a vaccine for the husband, which would work by suppressing his own sperm production. Dr. Kenneth Laurence, of the Population Council’s research unit at the Rockefeller Institute in New York, thinks this goal may be reached in three or four years. He and his associates have been injecting male guinea pigs with extracts of guinea-pig testes or sperm, and within six or seven weeks the animals become sterile. Their sperm production comes to a stop. While a single injection renders the animal sterile for 4 to 11 months, his sex-hormone output is not interfered with. He retains a normal sex drive and will mate if allowed to.

When the effect of the vaccine wears off, the glands resume the manufacture of sperm, at first with minor variations in sperm size. Eventually the sperm are normal in size and number, and the guinea pigs are able to father normal offspring. They have also had normal “grandchildren.” There has been one drawback, however, to the practical application of the male-vaccine method of birth control. The vaccine must contain an oil ingredient (called an adjuvant) for it to work efficiently. And the adjuvant makes such a sore at the point of injection that Doctor Laurence doubts most men would want to put up with that much discomfort. “But we are now working with another adjuvant that doesn’t produce a lesion,” he said. “Two injections would be necessary with this material, instead of one, and we haven’t yet tried it on humans, but we think we’ll be ready for this in a few years.”

A number of efforts are being made to produce something a woman could swallow following intercourse — the so-called “morning-after pill.” Dr. M.C. Shelesnyak, of the Weizmann Institute in Rehovoth, Israel, has found that a single dose of an alkaloid known as ergocornine, given to rats within six days after intercourse, will prevent the implantation of the fertilized ovum on the wall of the uterus. Doctor Shelesnyak has made preliminary studies with women patients, giving them 2-mg. tablets of ergocornine. The results were encouraging, but more work is necessary, he re-ported, to determine whether the method will prevent pregnancy without toxic side effects.

An American pharmaceutical firm has been experimenting with another morning-after pill that appears to destroy the fertilized ovum. But on one of the first field trials, women who had taken the pill unexpectedly became photosensitive. As soon as they went out in the sun, they got a sunburn. If these difficulties can be solved, the “morning-after pill” may become the ideal contraceptive.

III THE MORAL ISSUE

As the scientific revolution in birth control continues, solving human problems of many sorts, it also creates problems in morality. The new techniques eliminate fears that formerly deterred men and women from sex outside of marriage. With the deterrents reduced or gone, many people believe that the foundations of contemporary sexual morality may be threatened, especially the morals of the young. Newspaper headlines and book titles have cited “the new promiscuity’ facilitated by the pill. “Sex on the campus” has been a popular topic on television discussion programs, and college health officers have shocked parents across the country by publicly reporting that coeds come to them for prescriptions for pills. One said that when a girl at a Midwestern college recently made such a request, she was asked, “How old are you?”

“Twenty-one,” the girl replied.

“You have a particular man in mind?”

“Well, yes, I do.”

“Have you ever stopped to think that you might someday want to marry a man who holds virginity in high regard?” the doctor then asked.

“Yes,” she said, candidly. “But I’m not at all sure I want to marry a man like that.”

Indisputably, the revolution is making an impact on the lives and sex standards of the young, from teen-agers on up. Some authorities hope that the pill, prescribed for “the girl in trouble,” the youngster whose sex impulses cannot be controlled, will at least prevent the tragedy of the illegitimate, unwanted child. Dr. Edward Tyler, president of the American Association of Planned Parenthood Physicians, says his clinic in Los Angeles follows the principle of giving birth-control help to girls who have had a baby or who are brought in by mothers saying they are afraid the daughters will become pregnant. In New York the Planned Parenthood clinics follow a similar rule, and if parents or guardians are not available, the girls are accepted for help on referral by a social or health agency, a clergyman or a physician.

As for the controversial issue of sex on the college campus, some college officials doubt the pill is really encouraging freer sex activity there. Though ministers and moralists are highly vocal about “the rapid breakdown of sexual moral standards” among the young, many administrators insist that the situation today is no different from what it has always been.

“We have about five percent whom I would call sexually active,” observes Dr. Richard Moy, young head of the Student Health Service at the University of Chicago. “But that’s the same five percent we’ve always had. As for the pills, many girls have them when they come to school. Their family doctors at home have prescribed them. Or they borrow from each other or use the prescription of a married sister. Or they put on an engagement ring and get them as part of preparation for marriage. It’s not a very formidable task to obtain the pills.” A doctor on the West Coast says, “I’m sure many are sold in the drugstores without prescriptions, and there is certainly a lot of pill swapping, like sugar or eggs.”

Some investigators and many students insist that promiscuity is no more acceptable today than it was 40 years ago. Nevitt Sanford, professor of education and psychology at Stanford University, reports in the National Education Association Journal that on the basis of 12 years of studies at three schools-an eastern women’s college, a west-ern state university and a private college in the West, “there has been no revolutionary change in the status of premarital intercourse since the 1920’s.” He finds that between 20 and 30 percent of the women in his samples were not virgins at the time of graduation, and he thinks this is about the same percentage that existed in the 1920’s.

A number of college girls interviewed on these questions believe there has been an increase in pre-marital intercourse, but not in the direction of promiscuity. “There is a more sensible assessment of the problem than our parents used to make,” one girl explained. “I don’t think that promiscuity is condoned any more today than it ever was. But sex between people in love, people who hope or expect their relationship to grow into marriage, is much more common.” Nor do the girls think the rise in premarital sex is due to the pill.

Mrs. Mary-jane Snyder, of the Chicago Planned Parenthood staff, had a discussion on several topics with girls from a half-dozen colleges. On the subject of the pills, one of them said, “A lot of girls who were using other precautions have changed to the pills, I think-in fact, I know. But that’s just like changing from the horse and buggy to the automobile-it’s progress.” Another agreed. “No. I don’t think the pill has changed campus morals. The change was there. The pills just make it easier.” A third girl remarked, “Just think what the automobile did to increase sex activity. Don’t forget, though, there are still a lot of girls left with strong old moral fiber!”

“I wish it didn’t seem so old-fashioned to have high moral values,” one coed commented. “So many girls would just love to be able to say out loud that they think too much is being made of the importance of sex. The silly thing is that it’s sort of embarrassing to admit that you disapprove. It’s ‘the thing’ to sound modern and blasé even if you aren’t. For this reason, one can get a false impression of the percentage of girls who indulge.”

A faculty member at a big eastern university also doubts the pill has been a factor in changing campus morals, although he notes that “a great many girls are taking the pills, girls whose mothers send them to school all informed and ready.”

“It seems to me that the changed circumstances between the sexes is the crucial factor,” observes John Munro, dean of Harvard University. “The independence of women, for example. Going steady — the steady companionship of individual couples — is another aspect. Boys and girls are so much more companionable than ever before. Girls can do so much more, too. Families will send a couple of girls to Europe unchaperoned, for example. Or boys and girls start off together on some idealistic mission. But the young people, depending much on each other, become sexually entangled. Then one of them gets tired of the situation and the other suffers emotionally, and what you have is divorce before marriage, which can be pretty hard on these people.” But one girl asks:

“So long as we have no child — thanks to the pill — our relationship affects only ourselves. Why is this so wrong, when no one else gets hurt?”

A controversy over birth-control pills recently A flared on the campus of Pembroke College, the women’s division of Brown University, in Providence, R.I. A 19-year-old reporter for the Pembroke Record, a campus paper, called on Dr. Roswell D. Johnson, the Pembroke College health director, without identifying herself as a reporter, and asked for a prescription for the pills. In her article she wrote that she had “obtained a tentative prescription,” though she went on to say she was “refused a prescription for the time being on the grounds that she was under age.” Her story claimed Doctor Johnson did not mention any need for parental permission.

Doctor Johnson flatly contradicted the reporter on this point, saying he couldn’t even begin to talk to her about prescribing pills for her because she was under 21. “I also told her the only way she could get them was for her parents to write and request me to prescribe them,” he said, “and when I added, ‘I assume you’re not in the mood to write to them?’ she replied, ‘Oh-h-h, no-o-o!’

“Anyone over 21, however, is a free agent,” Doctor Johnson remarked, although he said he had actually prescribed the pills for only two unmarried students, and both of them were planning to be married. He added that if a girl asked him for a pill prescription he wanted to know why she wanted it. “I want to feel I’m contributing to a good solid relationship and not to promiscuity,” he said.

Mrs. Annabelle Cooper, executive director of the Washtenaw County League for Planned Parenthood, in Ann Arbor, Mich., finds no perceptible increase in the number of unmarried college girls under 21 applying to the clinic for contraceptives. “Those who want contraceptives can get them so easily at the corner drugstore,” she says, “that they usually don’t come to us. The pills aren’t available there without prescription, of course, nor the intra-uterine devices nor the diaphragms. But foams and condoms are.”

The Washtenaw Clinic’s policy statement on services to unmarried women is clear and decisive: Contraceptive services are given to all women 21 years or older, all married women under 21, and all unmarried mothers 21 or under “upon consideration.” “All women under 21 who are definitely engaged are given contraceptive service prior to marriage,” the statement continues. “All others are counseled, but given contraceptive service only with their parents’ permission.”

The premarital counseling and examination will be given as long as three months before marriage. “We have trained social workers who try to determine if a young girl is really going to be married,” Mrs. Cooper explained. “Occasionally we see a girl who is ‘premarital’ for as long as two years.”

Among young couples who have premarital intercourse, many actually refuse to use contraceptives. In addition to those who observe a religious prohibition, there are couples who believe that the use of any contraceptive is “too premeditated,” or is “not sincere.” “Some felt ‘planned intercourse’ was not romantic, and was too great a transgression of standards,” says Dr. Joseph Katz of Stanford. “I believe this is one of the biggest factors in unwanted pregnancies.”

Occasionally one finds a lonely, unloved girl who wants to become pregnant, even though she has no hope of marrying the baby’s father. And there is always the girl who tries to snare a boy by this means. In contrast with these girls is the one whose story a university official said he had every reason to believe. Even though she was not having intercourse, she still was taking the pills, she told him, because when she turned down a man she wanted it to be a matter of her own free choice and not because she was scared.

With her bewildering reasoning, the girl had touched upon what may be the only inarguable conclusion that can be drawn about the impact of the birth-control revolution on sex behavior: In cases where fear of pregnancy was the sole deterrent, the reliability of the new contraceptives has removed that fear.

IV THE RELIGIOUS CONTROVERSY

Nearly all religious denominations opposed birth control until a few decades ago, when one after another began to modify their positions. The Roman Catholic Church, almost alone, remained firm in its opposition. What the Church is now involved in is a struggle to extricate itself — without confusing the faithful — from a thick doctrinal web spun around the subject of marriage and sex in the early centuries of the Christian era.Neither the Old Testament nor the New specifically forbade contraception. The web of prohibition was purely an interpretation, woven by Popes and bishops and strengthened by the authoritarian tradition of the Church.

A penetrating study of this process — Contraception: A History of Its Treatment by the Catholic Theologians and Canonists — has been written by John T. Noonan Jr. of Notre Dame. Professor Noonan notes that contraception had been permitted by the Greek, Roman and early Jewish cultures and that the Christian teaching against it was mainly a reaction to the excesses of the Romans, who added to their licentiousness not only contraception but abortion. The Christian doctrine also reflected a new emphasis on the sanctity of all human life, including the seeds of life to be.

But there was a peculiar ambivalence toward sex in marriage, even in the Old Testament, and this, says Professor Noonan, is basic to an understanding of the development of the Christian ethic. On the one hand is the familiar glorification of procreation: “… and God said unto them, Be fruitful and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it.” Yet over against this are such strange verses as that in the Psalms, in which David, though the child of a lawful marriage, cries: “In guilt was I born and in sin my mother conceived me.” This and other passages, says Noonan, “furnish support to one stand of Christian thought, mistrustful of sex.”

Puritanical hostility to pleasure in sex, and to contraception, reached its peak with Augustine, in the fourth century. A former believer in Manichaeanism, he bitterly attacked the sex practices of that group, including its use of the sterile period. Ironically this was the original rhythm method, the only one now approved by the Catholic Church. As Noonan observes, “History has made doctrine take a topsy-turvy course.”

The pill was, of course, the catalyst that started the ferment of rethinking in the Catholic Churh, for it was obviously less “artificial” than jellies, foams and mechanical contraceptives. And in mimicking the action of nature’s hormones, the pill could be said to “regularize” the cycle and thus make the rhythm method more acceptable.

One of the first Catholic scholars to argue that the pill was licit on the basis that it did simulate normal physiology was the Rev. Louis Janssens, of the University of Louvain, Belgium. But within three months after his article appeared, in 1958, the late Pope Pius XII rejected this view. While Pius condemned the use of the pills to prevent conception, he nevertheless approved them when used for therapeutic purposes, even if “temporary sterility” was an indirect result.

This opened the door to more debate, a torrent of spoken and written words from priests and laymen alike, representing all shades of opinion and discussing female physiology and marital love with amazing frankness. Seldom in the history of the Church, which now claims a world membership of about half a billion, has an issue produced such sharp and vocal division among its leaders.

At the heart of most of the liberal argument was a pastoral concern for the dilemma of married parishioners. The Belgian cardinal, Leon Joseph Suenens, was moved to declare before the Ecumenical Council in Rome: “We are faced with the problem, not because the Christian faithful are attempting to satisfy their passions and their egoism, but because the best among them are attempting with anguish to live a double loyalty, to the Church’s doctrines and to the needs of conjugal and parental love.”

The cleavage among the priests left millions of Catholic couples confused. Many made their own decisions and chose the pills, with or without a twinge of conscience or a confession. Others had a tougher struggle. There was the girl of 18 who knocked one evening on the door of the Chicago Planned Parenthood headquarters. Mrs. Snyder, a warm and understanding staff member, let her in.

“The poor girl was in tears,” Mrs. Snyder recalls. “She told me she and her fiancé were to be married during his three-week leave from the Navy, and since both were Catholics she had asked her parish priest for a dispensation to permit them to use a contraceptive. She had a job and didn’t want to become pregnant until her husband came home again in a year. But her priest had refused, although, as she said. a friend’s priest in the next parish would have given the dispensation.

This girl said she didn’t mind if they had twelve children, once her husband was home to stay, but right now she didn’t want to take a chance because it was so necessary for her to keep her job. I really felt sorry for her. I was in tears myself before she left. But I didn’t want to advise her to go against her priest when she so plainly thought it would be the wrong thing to do.”

For another Midwestern woman, an accountant’s wife with three children under three years of age. there was a different outcome. Mrs. Jarvis, as we shall call her, had met her husband at a Catholic college, they had been married in the church and were “the best Catholics you ever saw until our babies began to come along so close together. Then we felt we had to do something.

“Our house has five bedrooms, but my husband said he didn’t want me to fill them up right away,” she said. “And when I’m pregnant, I’m in a bad mood most of the time. However, he didn’t think we could receive communion if we used ordinary contraceptives, because we’d have to confess each time as a sin.” Mrs. Jarvis, a young woman with delicate, sensitive features, leaned forward in her chair. “But for a thing to be a sin,” she said, “there are three things about it: First, you must think it’s a sin; second, it must be a grievous thing against God; and third, you must have done it voluntarily. Well, we don’t think the pills are a sin, and our young priest said he saw nothing wrong with them either. So we don’t confess them, and we can go to church and take communion. We didn’t learn about this until just a few weeks ago when the young priest told us. Young priests seem to be more understanding.

“The best time to be a Catholic,” Mrs. Jarvis concluded, “is when you’re very young or very old. In between is this problem. They say the Catholic Church is hard to live in and easy to die in, and it’s true. But the pills, which so many in the Church are beginning to approve, will be a great help.”

Hopes for liberalization of the Church’s position appeared to suffer a setback last October, when Pope Paul spoke to the United Nations in New York. Three quarters of the way through his eloquent plea for world peace, he sounded what to many seemed a discordant and disappointing note. “You must strive to multiply bread so that it suffices for the tables of mankind,” he said, “and not rather favor an artificial control of birth, which would be irrational, in order to diminish the number of guests at the banquet of life.”

The Pontiff’s remark was open to instant and differing interpretations, as papal utterances often are. Some observers said its import hinged on the Pope’s own definition of “artificial.” Others thought he simply wanted to discourage an international campaign for contraception.

One of the official bodies studying the problem is a special papal commission on problems of marriage set up by Pope John XXIII. Pope Paul enlarged the commission to 56 members, including clergymen, scientists, doctors and a few married couples. The commission failed to agree on a recommendation during the Ecumenical Council, but the council’s final declaration on marriage, which reflected intervention by the Pope, indicated that he had asked the commission to continue its study of the birth-control question.

The pertinent passages in the council’s report on “The Church in the Modern World” were ambiguous, however. They said the faithful “may not undertake methods of birth control which are found blameworthy by the teaching authority of the Church in its unfolding of the divine law.” At present this rules out all but abstinence and rhythm. At the same time they made a significant change by placing conjugal love for its own sake on an equal plane with procreation. Some observers think this opens the way to eventual approval of many forms of birth control.

V THE BENEVOLENT CONSPIRATORS

While the Catholic Church has not significantly modified its official stand on the birth-control issue, the fact that the Pope and his advisers have been considering changes has had an effect. For one thing, the possibility of future change has served to inhibit many of the Catholic politicians who have traditionally fought the operation of birth-control clinics. “The Catholic Church found what the Pope was going to decide,” said Dr. Alan F. Guttmacher, the eminent obstetrician, gynecologist and president of the Planned Parenthood Federation. “They didn’t want to hold the line against birth control and then discover that the Pope will say the sky’s the limit.” Several states repealed their anti-birth-control laws last year, and Connecticut’s law was declared unconstitutional, with almost no opposition from church groups. Richard Cardinal Cushing of Boston, whose autographed photo hangs in Guttmacher’s office, has actually said he favors the legalizing of birth control. He reflects the new attitude of many Catholic prelates in saying that “Catholics do not need the support of civil law to be faithful to their religious convictions, and they do not seek to impose by law their moral views on other members of society.”

The revolution in birth control is far more, of course, than a rebellion against rigid church teachings. It is a wave of human thought and emotion which was channeled into worldwide action by a group of what might be called “benevolent conspirators.” They are industrialists, physicians, scholars, publishers, retired generals—men and women who are convinced of the urgency of the cause and are highly persuasive in advancing it.

Doctor Guttmacher recalls a routine mail appeal of several years ago which brought a $100 check from the president of a large corporation. “We followed this up with a personal contact,” he said, “and now this man contributes $100,000 a year to the Planned Parenthood funds and is one of our most effective leaders. The movement also gained much momentum when Cass Canfield of Harper’ s became chairman of our executive committee six years ago. He is one of the most respected publishers in the United States, and his influence has been great.”

Some years ago Mrs. John D. Rockefeller Jr. became interested. She enlisted her husband, and their son, John D. III, continued the family’s involvement. Doctor Guttmacher recalls that John D. III was distressed by the poverty and acute overcrowding he saw during a trip to the Far East in 1952. “He conceived the idea of the Population Council, and with Gen. Fred Osborn, then one of his advisers, set it up. It is now one of the strongest forces we have, especially for carrying on research.”

Although the birth-control organizations operate no lobbies, their officers often inspire important moves by other groups, and they make frequent calls on members of state and federal governments. Last spring a large group of Nobel Prize winners of America and Europe addressed a statement to the Pope, urging him to “give due weight to the ever-growing opinion” in the world that unwanted children are a source of unhappiness and distress and that parents should be able to limit their families to the number of children “which can be cared for and cherished.” Dr. Edward L. Tatum, a biologist of the Rockefeller Institute, and Dr. Peter B. Medawar, a British biologist, were the two Nobel laureates who moved the idea ahead and got 81 signers to the letter.

Doctor Guttmacher, when not touring the world on behalf of foreign birth-control programs, gets to Washington once or twice a month. There he may confer about family-planning services for the wives of military personnel or American Indians (both groups are entitled to such services under current government policies), or push for wider use of anti-poverty funds for birth control. (A total of $766,000 has gone to 13 birth-control projects.)

A change in government attitude at the White House level has had much to do with speeding up the anti-poverty clinics, Doctor Guttmacher believes. “President Johnson sent up a trial balloon early last year, saying he would ‘seek new ways to use our knowledge to help deal with the explosion of world population.’ I guess the balloon didn’t burst because he sent up an even bigger one six months later when he said at the United Nations in June that five dollars spent on population control is worth one hundred in economic aid. What else do you need for a green light?”

The turnaround in government policy can be credited in large part to Gen. William H. Draper Jr., now a vice-chairman of Planned Parenthood, and a famous report he wrote in 1959. He was then chairman of the President’s Committee to Study the United States Military Assistance Program.

General Draper had first come into contact with a major population problem during a trip to Japan in 1948, where he saw the tremendous congestion caused by the repatriation of millions of Japanese from Manchuria and the Chinese mainland. “In 1958, members of our committee — a high-level group of responsible citizens — visited all the countries receiving aid from us,” General Draper recalled recently, “and in some we found the standard of living was actually going down because of the high birth rate. We agreed unanimously in our recommendation, that ‘the United States should assist those countries with which it is cooperating in economic-aid programs, on request, in the formulation of their plans designed to deal with the problem of rapid population growth.’

“Of course, the recommendation was carefully worded.” General Draper pointed out, “and there were two words — ‘on request’ — which saved it.”

But at the time the Draper report was submitted, even those two words didn’t save it, a fact that shocked its authors. “We never thought the recommendations would not be accepted,” General Draper said, “and then I picked up the paper one morning and read that President Eisenhower had said that the last thing he wanted our Government to do was to give birth-control advice to foreign countries.” Even before Eisenhower spoke, Draper said, “the Catholic bishops blasted the report, and that was the worst thing they could have done, because it did become a big issue, and all the candidates were asked how they stood on it, Kennedy coming off very well.”

The idea had been planted, and it took root. Though Eisenhower refused to involve the Government in foreign birth-control programs, he approved of private organizations in this field. Later he changed his mind on government participation. In a Saturday Evening Post article of October 26, 1963, he explained he had rejected the Draper recommendations because he felt that using federal funds on population-control problems abroad “would violate the deepest religious convictions of large groups of taxpayers.” But, he wrote, “As I now look back, it may be that I was carrying that conviction too far.” In 1964 General Draper persuaded Mr. Eisenhower and another former President, Harry S Truman, to be honorary co-chairmen of Planned Parenthood-World Population, thus lending their influence to foreign as well as American phases of the program. All this made it easier for President Lyndon Johnson to make birth control a national policy.

VI BIRTH CONTROL AND THE LAW

While the “benevolent conspirators” were slowly changing our attitudes toward birth control, there remained a vast network of restrictive laws, the principal effect of which has been to deprive low-income families of birth-control information and services. This legislation began with the federal law of 1873, instigated by the busy New England anti-vice crusader, Anthony Comstock. Some 30 states soon passed “little Comstock laws,” most calling birth control “obscene and immoral.”These were the statutes under which Mrs. Sanger’s pioneer meetings were raided, her clinics closed and she herself jailed. In 1936 another famous birth-control figure, the late Dr. Hannah Stone of New York, was involved in a case known as “The United States vs. One Package.” The package contained diaphragms sent to her from Japan and seized by U.S. Customs. Mrs. Harriet Pilpel, a New York lawyer, argued the “package”case for Doctor Stone and won. In the fall of 1963 Mrs. Pilpel was called again when the St. Louis postmaster held up the mailing of 50,000 samples of an aerosol foam contraceptive on the grounds that they were not addressed to doctors. The product, Emko, is made as a crusading and semi-philanthropic sideline by a gregarious white-haired St. Louis manufacturer, Joseph Sunnen.

Sunnen, who has donated thousands of bottles of Emko and hundreds of thousands of dollars to birth-control programs, always carries a few Emko packages in his pocket, passing them out to friends and casual acquaintances after asking them how many children they have. The samples were being sent to women who had clipped coupons from Emko ads appearing in 19 magazines. Again Mrs. Pilpel obtained a favorable ruling. one that said unless the postmaster could prove the packages were being mailed for unlawful purposes, they could go through.

The toughest Comstock Law in the land was Connecticut’s 1879 statute making the use of any drug, medical article or instrument to prevent conception an offense punishable by a fine and up to a year in prison. Anyone who “assists, abets, counsels, causes, hires or commands another to commit any offense” could be similarly prosecuted.

The law was enacted by a Protestant Puritan legislature and was kept on the books, in the face of 28 legislative repeal efforts in the past 40 years, by what has been described as “a small but very articulate and well-organized group of Roman Catholic extremists.” Connecticut doctors were not barred from giving birth-control advice to private patients in their offices, but the state law blocked welfare clinics from giving such advice to their clients. Eight or nine birth-control clinics were closed under the law in 1939 and many of the doctors and nurses in attendance were arrested.

When Dr. C. Lee Buxton arrived from New York in 1954 to head the department of obstetrics at Yale’s School of Medicine, he was both amused by the law’s silliness and distressed by its social injustice. To prohibit individual couples from using contraceptives would, he observed, “require police power as a third party on the connubial couch,” a thought whose “farcical implications have all kinds of possibilities.”

But what sharpened his determination to do something about the law was the death of several women patients and the permanent incapacitation of another from medical problems seriously aggravated by unwanted pregnancies. All these women had sought contraceptive advice and been unable to get it. “I was brooding about these patients at a cocktail party one evening,” Doctor Buxton recalls, “when I met Fowler Harper, then professor of law at Yale. I asked what he thought about the Connecticut law, which was actually preventing us from giving birth-control information to ward patients in the hospital. He said he thought it was a hell of a law. So I got some cases worked up for legal trial, and Harper filed suit to challenge the law’s constitutionality, on the ground that it violated the 14th Amendment assuring citizens the basic civil and human rights of personal liberty. Professor Harper died last year, but Miss Catherine Roraback, one of his former students, masterminded the case for us.”

This case was lost in the lower courts, and the Supreme Court refused to consider the constitutionality on the grounds that the law was in fact a dead issue and was not enforced. Well, if the law was a dead issue, the thing to do was to open a contraceptive clinic at once, and Mrs. Estelle Griswold. executive director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut, in cooperation with Doctor Buxton as director, prepared to do so. On November 1, 1961, the clinic opened its doors to the public. On November 10 it was closed, by order of the prosecutor, Julius Maretz.

In closing the clinic, New Haven authorities had to contend with a small, white-haired woman in her 60’s with a lively sense of humor and a relish for a good fight. The shutting down of Mrs. Griswold’s clinic on that November day was a challenge she met with delight.

“My real concern had been that we were only fighting feathers,” she said, “that no one might oppose us. This bothered me because birth-control services would still have been illegal. But when we announced the clinic was open, we were swamped with phone calls, and our appointments were soon set up for two or three months ahead.”

What forced the legal move against the New Haven clinic was a series of accusations by a man who went to one official after the other demanding that the clinic be closed. “He made a lot of wild statements about me on the radio,” said Mrs. Griswold, “and said that every minute the clinic was open a baby wasn’t being born. Shortly after one of his radio broadcasts he went to the prosecutor with what was almost an accusation, and there was nothing for the prosecutor to do but send the detectives over to the clinic to see what was going on.”

In the course of appealing the case from the lower courts, where he and Mrs. Griswold were fined $100 each and released on $250 bond, Doctor Buxton wrote to experts at every medical college in the country, asking for written support. He got it, even from many Catholic medical schools. Finally, on June 7, 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its historic 7-to-2 decision. Justice William 0. Douglas, in writing the majority opinion, declared the case concerned “a relationship lying within the zone of privacy created by several fundamental constitutional guarantees” and said the Connecticut law “in forbidding the use of contraceptives rather than regulating their manufacture or sale, seeks to achieve its goals by means having a maximum destructive impact upon that relationship.

“We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights‑older than our political parties, older than our school system,” he concluded. “Marriage is a coming together for better or worse, hopefully enduring and intimate to the degree of being sacred.”

The two dissenting justices, Stewart and Black, both thought the Connecticut law offensive but constitutional.

Within days after the Supreme Court decision the New York legislature modified its 84-year-old “Comstock law” to remove all restrictions on the dissemination of birth-control information and to permit sale of contraceptives to everyone over the age of 16. Although the law had not been enforced for years, it had been resurrected by the Catholic Welfare Conference in an effort to stop birth-control activities by the State Board of Social Welfare.

Later in the summer the Massachusetts legislature defeated a similar repeal move, but this was the one exception to last year’s general easing of legal and administrative restraints. Ohio and Minnesota joined New York in clearing away restrictions from their statutes.

Seven states — California, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan and Nevada — adopted positive legislation to authorize or encourage public family-planning services. And according to a Planned Parenthood survey more than 40 states have made administrative decisions favorable to such programs over the past four or five years.

The long and bitter political battle in Chicago and Illinois ended last June when the state legislature passed a resolution authorizing state agencies to provide birth-control services. And the Chicago Board of Health, under the adroit persuasion of its president, Dr. Eric Oldberg, a prominent neurosurgeon, cautiously began family planning services in nine of its 39 city health centers. His viewpoint conflicts sharply with that of Dr. Karl A. Meyer, 79-year-old medical superintendent of the huge Cook County Hospital, which still has no birth-control clinics even though its annual delivery of 18,000 babies is the largest of any hospital in the country. “Birth control,” Meyer has remarked, “is a socio-economic problem, not a medical one.”

However you define it, birth-control information has been denied to the many women who have sought it at Cook County. In an interview on CBS-TV, one woman said she asked a doctor at Cook County if he could help her stop having children. “He told me no, I was too young,” she said, “and was good for twenty more.”

VII THE WORLD CRISIS

Spectacular and incisive as its 1965 battles have been, the birth-control revolution has just begun on those troubled frontiers of the world where the population has outraced the supply of food, housing and jobs. Humanity, now numbering almost three and a half billion and expected to reach over 6 billion by the end of the century, has not yet filled up all the earth’s living space. But in many countries the conquest of diseases that used to hold the population in check has been so rapid that the economy has not been able to keep up, and living standards have steadily fallen. “The world-population crisis is no longer a future fear — it is already with us,” General Draper warned last month. “One half of the world’s population and two thirds of its children do not have enough to eat. The stark fact is that if the population continues to increase faster than food production, hundreds of millions will starve in the next decade.”

India, her chronic food shortages worsened by the lack of normal monsoon rains, “is experiencing semi-starvation today,” General Draper commented, “and may see full-scale famine this coming year.” Prime Minister Shastri has asked his people to observe “ supperless Mondays” and food rationing has been ordered in New Delhi. Reports from Orissa, a state in eastern India on the Bay of Bengal, say that some farmers, unable to feed their families, are selling not only their possessions but their children as well.

Latin America’s living standards have declined as its swelling population crowds from the country into the cities. Less food is produced and eaten there per capita than before World War says General Draper, and there has been a shocking 10 percent decline since 1960.

Dr. Alberto Lleras, a former president of Colombia, told Sen. Ernest Gruening’s committee on population control that South America’s problem has been greatly aggravated by mechanization on the farms and automation in industry. “Millions of peasants, thrown out of work in the country, become a bedraggled army of nomads,” he said, “flocking to the cities and finding no work, or grossly inadequate employment there.

“Worse yet,” Lleras added, “economic development is not achieving its purpose — to create jobs. … Latin America is breeding misery, revolutionary pressures, famine and many other potentially disastrous problems in proportions that exceed our imagination.”

Both Lleras and General Draper insist that population problems in Latin America and other crowded parts of the world cannot be solved without birth control. Unfortunately, the revolution has not yet touched the great majority of the world’s people. According to George N. Lindsay Jr., brother of New York’s mayor and the new chairman of the board of Planned Parenthood, “Modern contraceptives are still largely unavailable among three fourths of the world’s people. Even in the U.S., where family planning is now a deep-rooted tradition among the more fortunate, nine out of ten impoverished women still lack birth-control information and assistance.”

Where the new weapons of the birth-control revolution have been given a fair test, the signs are encouraging. Under the Korean National Health program, doctors have been fitting women with intra-uterine devices at the rate of 15,000 a month. Their aim is to cut the birth rate in half in the next three years, and in one test area a 20 percent reduction was achieved in just one year. In Taiwan the program is under non-government sponsorship, with Population Council assistance. The goal is to install 600.000 loops by 1969 and slow the island’s population growth rate from 3.2 to 1.8 percent. In selected areas the birth rate has already declined 60 percent.

U.S. Ambassador to India Chester Bowles has said that India expects to reduce its annual birth rate from the present 42 per 1,000 of population to 25 over the next decade. Mr. Bowles displayed a New Delhi newspaper with a Ministry of Health ad that read: “A small family is a happy family. Plan your family the loop way.”

At this point no one can say what the ultimate in conception control will be — a loop, a better pill, a longer-lasting injectable, a safe vaccine. What is important is that the human family and the human race have at last a means for determining, with unprecedented re-liability, their increase. “By placing the creation of life under the guidance of man’s ethics and intellect,” says Donald B. Straus, former chairman of Planned Parenthood, “we can achieve a reverence for life which assures that every baby shall be a wanted baby and shall have room in the family for love.”

We live in a finite world, with finite resources. Yet we are endowed with a brain of almost infinite inventiveness and capacity, and it has given us the birth-control revolution. We can reasonably expect that in time we shall be able to occupy our world without crowding and exhausting it.

Letting Go

Remember how, in old movies, when someone is dying, the family all gathers around the sick bed and the ailing family member summons his energy to sit up and tell everyone he loves them, then pitches over and goes to his reward? Well, if it was ever like that in real life, it’s not anymore.

In the past 10 years or so, I’ve sat at the bedsides of several friends and family members who have passed on. One week before my mother died at 88, she was ailing but communicative — even cracking jokes — in her hospital bed. But five days later she’d entered “transition,” that purgatory-like state when the body is still alive but the brain has begun shutting down. She was breathing, but unconscious. The nursing staff, knowing the end was near, asked what we wanted to do if her heart stopped. Would we want them to take heroic measures to restart it, very likely breaking her ribs in the process?

No, we said. She was tiny and frail with an intractable condition, and we knew she would not have wanted it. So we sat at her bedside, whispering to her, holding her hand, saying goodbye.

In recent years, the very definition of death has changed, from a precise endpoint to a fuzzy continuum of decline that can be extended artificially for quite some time. And for this, we can thank, or blame, science. My mother got off easy. Some elderly people, well past the point of having even a slender chance of returning to a robust life, become medical pincushions as doctors and nurses see how long they can keep the heart beating.

In “Final Independence,” Jeanne Erdmann describes science’s Faustian bargain unsparingly: “Antibiotics, defibrillators, feeding tubes, and ventilators are lifesaving tools that sometimes become weapons to prolong life against our will.”

How much suffering should a person have to put up with at life’s end? There are advance directives that are supposed to protect you from needless suffering, but as Erdmann points out, it’s all too easy for those wishes to be ignored. We should never forget that medical professionals are trained to cure, not to ease their patients’ passage. Moreover, in today’s litigious world, many doctors are fearful of being sued for negligence. All it takes is one family member arguing that a life-saving procedure was inappropriately withheld.

It’s time for courts to protect doctors who, with family support, agree to mercifully withhold treatment. It’s time for medical schools to develop curricula to help the next generation of doctors learn how to say “this is the end” when the outlook is hopeless. It’s time to help dying patients and their families get through this most difficult part of life’s journey with the least amount of suffering.

Final Independence

Antibiotics, defibrillators, feeding tubes, and ventilators are lifesaving tools that sometimes become weapons to prolong life against our will. None of us wants to live for years in a nursing home rendered unconscious by late-stage dementia; or brain-damaged by strokes; or on and off ventilators with recurring pneumonia, growing so frail we lose the choice of an unfettered death at home. We grow determined in our wishes. We formalize end-of-life plans asking for comfort care only, no heroic, invasive, or futile medical procedures, no artificial food or hydration, minimal feeding. We assemble and legalize these plans. We calm our fears.

It sounds rational and safe. But in reality, the faith we place in legalized directives, or in the medical professionals charged with enforcing them, has proven unwise. Medical professionals ignore such directives, no matter how carefully we’ve crafted them, particularly if we end up in a hospital or nursing facility.

I’m not talking about assisted suicide. I’m talking about plans that specify withholding treatment, such as a ventilator, a feeding tube, or antibiotics for pneumonia, for a person who won’t recover, prolonging death even over fierce objections from family members. This situation results, in part, because directives go against the culture of medicine, which focuses on healing, on doing everything possible even if what’s possible proves futile. …

—

This article was originally published by Aeon Media (Aeon.co, Twitter: @AeonMag).

Purchase the digital edition for your iPad, Nook, or Android tablet:

To purchase a subscription to the print edition of The Saturday Evening Post:

Five in the Fifth

Jerry stuffed a tray of dirty dishes onto an overcrowded utility cart then rounded the corner to Mildred’s room.

“Hi, gorgeous,” he sang cheerfully. “How’s my girl today?”

Millie lifted her head a fraction as guttural sounds erupted from her throat.

Jerry turned abruptly. She was making an attempt to reply. “Millie, you’ve finally decided to speak to me.”

The old woman’s body jerked toward him causing her hand to flail over the side of the wheelchair. Jerry looked down at a green-shaded Abraham Lincoln peaking through gnarled fingers.

“What’s this?” he asked. “We’re not allowed tips, Mill. But thanks just the same.”

Agitation took over as Millie’s head began to shake. With great effort, she opened her mouth to have “Santa” escape from her lips.

“Santa! You’ve got the wrong holiday, Mill. Christmas is past. We’re coming on Easter.”

Millie waved her hand in frustration. “Santa,” she repeated again. “Five, five ’n fifth.”

“I can’t take your money, Mill. I’d be fired tomorrow. I think you’re a little confused. The nurse will be in shortly. You need a good night’s sleep.”

The television was rolling but Jerry never looked up. Televisions played continuously in every room of the nursing home. His shift was almost over and he was anxious to get to the locker room. He’d been at the Evergreen Nursing Home so long that the odors were second nature to him, but his buddies would puke if he showed up at Zingers before showering. Cleaning vomit from the patients came with the job; dealing with their crap was another issue entirely.

At 7 o’clock, he stepped through the door of Wing Zingers. His friends had their Buds in hand and were sucking them up. He grabbed a Saranac at the bar, then slid into a booth beside Mike.

“So my good men, tell me what’s happening.”

Canyon lifted an eyebrow. “Same ole, same ole.”

The “same ole” was just as boring with the beer bottles emptied. Jerry stretched to catch a glance at the television anchored on a wall high above them. A sports commentator caught his attention. He turned to his buddies with eyes popping.

“Did you hear that?”

“Hear what,” Mike asked dryly.

“Santa Anita! The fifth horse in the fifth race had the biggest payout in the track’s history.”

“Didn’t know you were playing the horses,” Canyon remarked with mild surprise.

“I don’t. It’s just that an old woman at the home tried to give me a fin today. She said Santa, five in the fifth.”

The other men roared in laughter.

Canyon wiped tears from his face. “You’re telling us some old bat at the nursing home knew that horse was gonna win. You gotta be kidding.”

“I don’t know.” Jerry was clearly puzzled. “She had the five in her hand.” He lifted a shoulder expressing doubt. “She said five in the fifth.”

Mike gave him a patronizing look. “Listen to yourself, man. You say she had a five in her hand. Five, fifth, it’s all the same. She was getting mixed up, probably wanted change. You’ve been at that place too long, Jer. I think you’re losing it.”

Canyon shook his head. “I never knew why you took that job in the first place.”