For thousands of years, doctors relied on opiates to relieve suffering. It was one of the few compounds that could offer immediate, guaranteed release from pain. And opiates have always played a role in America’s story.

The first opiates probably came to America in 1620, arriving in the trunk of the doctor who had sailed on the Mayflower.

Opium was still in use during the Colonial Era. Thomas Jefferson, for example, relied on opiates to ease his suffering in his final years. (Ever far-sighted, he planted opium poppies on his property. They continued growing at Monticello until the 1990s, when the Drug Enforcement Agency pulled them up.)

In the 19th century, the most common opiate was laudanum, a mixture of opium and wine. It was widely available (without a prescription, of course) and it cost less than alcohol.

In those early times, there was no stigma attached to its use, or abuse. The Post, in 1833 recommended it for treating bee stings or persistent coughs (combine molasses, vinegar, wine mixed with with 40 drops of laudanum).

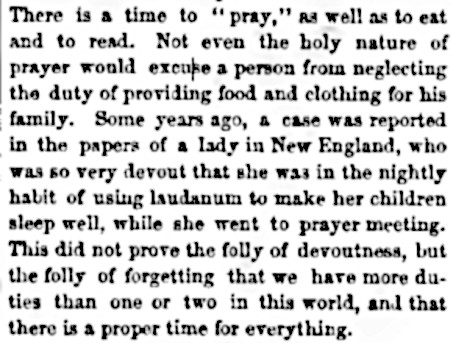

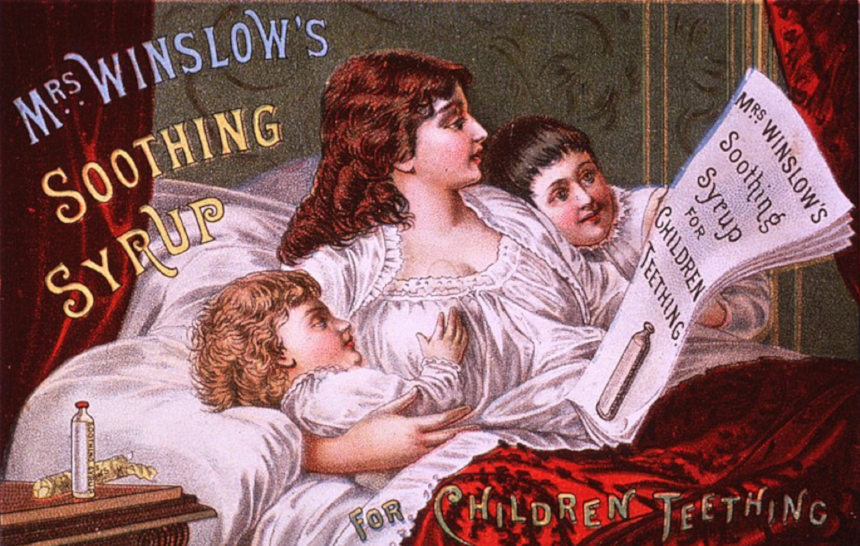

It could also be used on children who were teething. But adults also found laudanum was an easy way to get their infants and older children to sleep, especially since the side effects were little known at the time. In 1858, The Post reported that one lady in New England solved her baby-sitter problem by putting her children into a deep sleep with laudanum so she could attend nightly prayer meetings.

In an 1864 Post article on factory towns, the author described the desperate state of child day care. Working women might leave their offspring with elderly caretakers who dosed the children with laudanum so they’d remain quiet and manageable.

The majority of opiate addicts in the late 1800s were middle- to upper-class women. They turned to laudanum because, in the Victorian era, they had limited access to alcohol. No respectable woman could buy liquor or enter a saloon.

Laudanum was considered a source of inspiration for artists, composers, and, especially poets. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning were all familiar with, if not addicted to, laudanum.

In the post-Civil-War years, opiate use rose sharply. Many wounded veterans, who’d been given the painkiller in military hospitals, became life-long addicts.

But there was even greater use among civilians, some of whom became addicted when trying to escape the pain of a chronic illness, bankruptcy, unemployment, or the death of a loved one. This heavy use of laudanum caused the death of thousands. And deliberate overdosing became the most common means of suicide.

Later in the century, the dangers of the drug were becoming more obvious, as reflected in the Post’s coverage. An April 6, 1872, article stated, “A careful inquiry among druggists reveals the fact that there are in New York city about 5,000 confirmed users” (out of a population of less than 100,000).

In a later article, the editors wrote:

The use of laudanum as a drink is fast increasing. In most cases it is used with alcohol to lessen the irritating effect of this drug, or the result of excessive alcohol, as a sedative, or as a stimulant. In England a favorite preparation used after drinking is called a “Pick me up.” In some large cities, druggists give compounds of laudanum and ginger under fanciful names, and these are resorted to always after, in place of alcohol. This accounts for the enormous sales of opium, of which not over one fifth is used in medicine.

Laudanum abuse wasn’t just a big-city problem, either. An 1894 editorial reported, “Anyone who doubts the continued prevalence of the opium-taking habit would soon be convinced if he glanced over the chemists’ preparations for a rural market-day.” Country folk, it continued, took laudanum not to alleviate pain, but to bring “artificial excitement” into their sedate, rural lives.

Doctors had been alerted to the dangers of addiction starting in the 1870s. But the warnings had little chance of reaching doctors living in the country. Even among physicians who knew better, it was difficult not to prescribe laudanum for their patients in agony; there simply was nothing else. And opiates continued to be the prescription of choice for patients.

Even as America awoke to the dangers of opiates, little was done to discourage its use. Between 1898 and 1902, the opium and morphine business more than doubled. The rate of addiction was nearly three times higher than in the mid-1990s.

A reforming spirit emerged among Americans in the 1900s. One of the chief areas of concern was the unhealthiness of food and drugs, many of which included opiates.

Another factor was an outcome of the recent Spanish-American war. The U.S. had taken over the administration of the Philippines, which had a thriving opium trade. President Theodore Roosevelt requested an international opium commission to exert some control over opiate traffic. But he realized the U.S. couldn’t control drug traffic in the world if it couldn’t control it at home.

In 1909, Congress finally criminalized the importation, possession, or smoking of opium. Later, the 1914 Harrison Narcotics Tax Act required all importers, manufacturers, or dispensers of any opium product to register with the government.

The opioid epidemics of then and now are similar in many ways, but there is one great difference. Doctors and opioid addicts in the 1800s could plead ignorance of the dangers within these substances. We don’t have that excuse today.

Featured image: “The countess, having taken a dose of laudanum nears death” Engraving by Louis Gérard Scotin after William Hogarth, 1745. (Wellcome Collection gallery, CC-BY-4.0)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This frightening feature is sadly simultaneously historic and current. I was not familiar with laudanum before reading about it here. I can certainly understand and sympathize with the desire and need for the opiates in the previous centuries for genuine pain relief, and the good feeling of getting/being ‘high’, for the right and even wrong reasons.

It’s easy to criticize or for one to think they’re ‘superior’ to those that would fall into such a trap of addiction, or even using any of these drugs in the first place. Used in the right amounts at the right times for the right reasons they’re a God send; especially morphine. I was in terrible pain after dislocating my shoulder in a 2008 freak accident at home.

I drove myself to the Sherman Oaks ER, and the next thing I knew it was 4 hours later with no pain. I was given a morphine injection and it was WONDERFUL I got a prescription for the lower dose pain killer (capsule) version which (with therapy) got me through it taken as directed. Although there was a slight ‘high’, I didn’t care about that; just killing the pain. I healed completely but not without a lot of painful therapy. My right shoulder/arm of course. If it had to happen, I wish it had been the left instead, but no. The incident made me realize how and why someone could become addicted to morphine.

The examples cited here of use and abuse especially in the 1800’s show that this is an age-old problem that has had increases and decreases over the decades and centuries and will continue to do so, along with most other age-old problems. Enough people will always abuse drugs with bad consequences. Animals out in the wild know which plants to eat for pain relief, to get high, or both. Unlike people though, they seem to have a lot more sense in not over doing it. No surprise there, unfortunately.