Sacrifice.

That word embodied World War II — at the battle front and on the home front, served up with large helpings of prudence and patriotism.

Sacrifice was rendered in the posters that encouraged Americans to buy War Bonds, do without and/or with less, posters that have become collector’s items. They were embodiments of the big issues of the war years and small things to remember to do (or not do) each day.

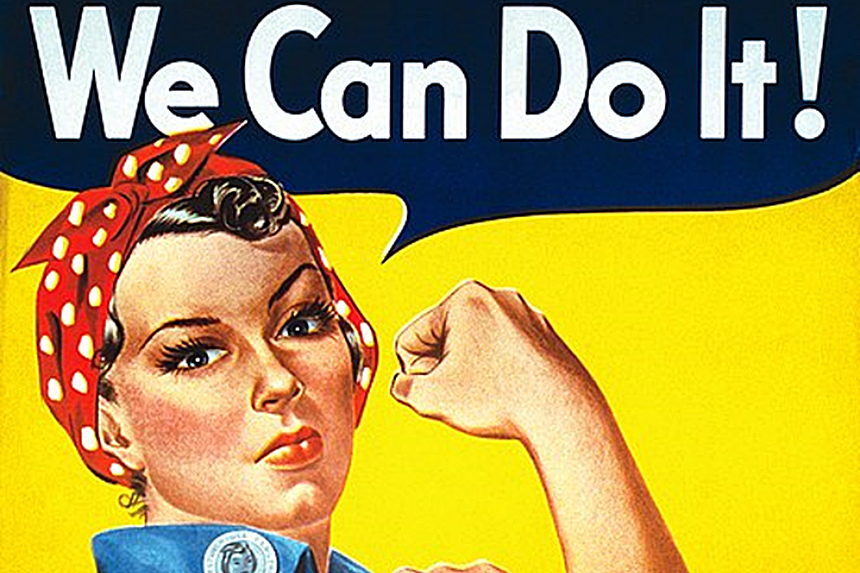

I remember them well. Rosie the Riveter was the most famous of all — the embodiment of the Can Do spirit, epitomizing the sea change of women replacing men in the workplace, in this case the factories that turned out the war supplies.

Rosie first appeared on a Norman Rockwell cover of The Saturday Evening Post, May 29, 1943 — not the same girl, though, on the poster that came to be as familiar to Americans as the pin-ups of movie stars like Betty Grable. About the only thing the two Rosies have in common is their blue work pants and shirt. In the poster, Rosie’s sleeves are rolled up for work, her hair covered by a red and white polka dot bandana. It’s the more colorful of the two. It’s Technicolor-bright — the yellow background, blue coverall, red and white bandana, an icon of World War II.

The World War II posters were not only a highly visible part of the war but a highly important one.

So much so that General George C. Marshall, Army chief of staff, the man to whom the supreme commanders in Europe and the Pacific reported, had to approve each poster. I learned this some years ago when I was working with the executive director of the George C. Marshall Museum and Library at Lexington, Virginia., on an exhibition of the museum’s collection of World War II posters. He told me that General Marshall reserved the right to approve all posters. My friend didn’t say when the policy started, just that it was in effect for most, if not all, of the war.

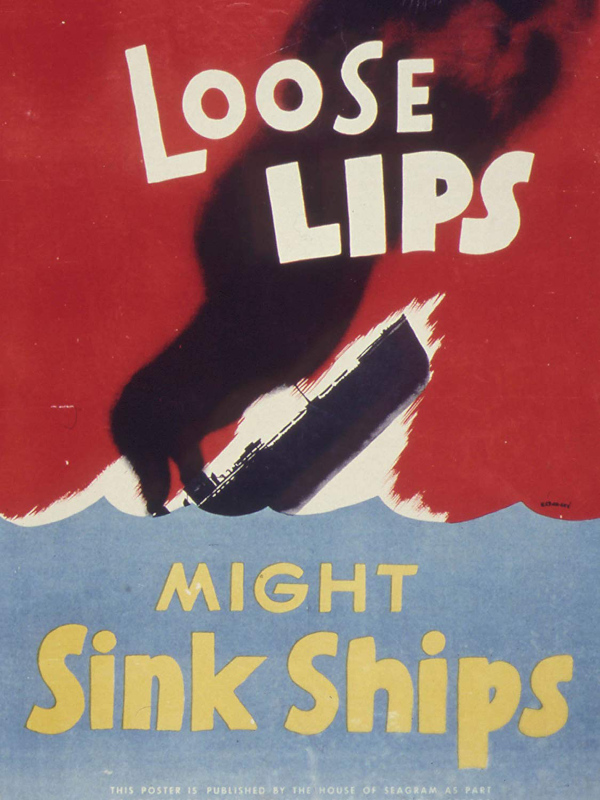

Probably the best known poster after Rosie the Riveter was one directed to those of us at home: Loose Lips Sink Ships. This one expressed the concern by authorities that we might inadvertently help the enemy.

In an America where we’d grown up in a land of free speech and friendliness — how-dee-do and what’s new? — we had to be cautioned not to in any way pass along information — part of our otherwise casual conversation about a neighbor’s son or the guy who’d delivered our groceries — that might reveal troop movements.

The drawing in the background showed a ship, its smokestacks and aft deck about to disappear beneath the water. The white letters spelled out the words that would become so familiar they slipped into the language.

When the House of Seagram printed posters for display in taverns — noting that “This Poster is Published by the House of Seagram as part of its contribution to the National Victory Effort” — it used the same illustration but added the word Might. Many a poster is out there with the qualification, but the phrase that came down to us is Loose Lips Sink Ships.

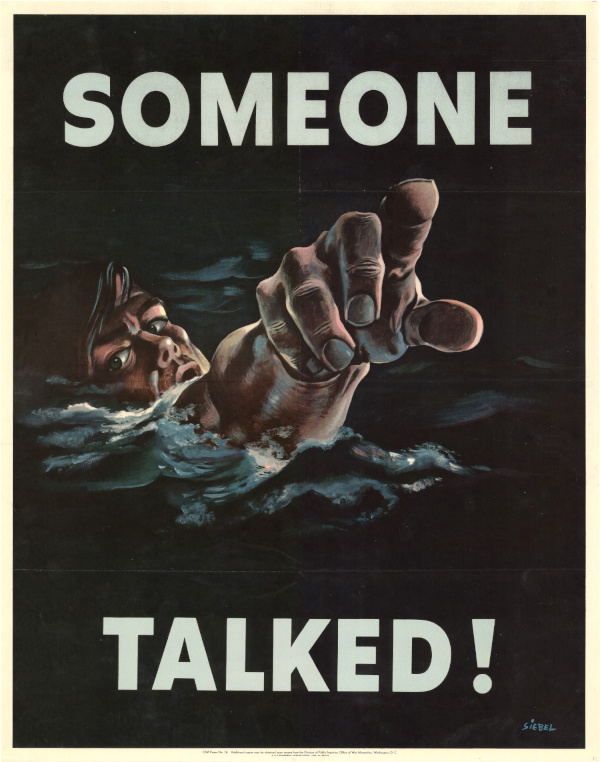

Another poster reminding us to be careful about what we said depicted a young man’s face barely visible above the dark water, his right arm outstretched, fingers extended, desperate for something to grasp, cling to, keep from slipping beneath the water and drowning. The message driven home: Someone Talked!

It should be understood that while the posters have been labeled propaganda in some cases, they basically offered guidance, encouraged certain activities, and spurred us on. We didn’t need to be wooed. Or won. We supported the war. Wholeheartedly.

We knew what the guys out there fighting were going through. We might not have had television then, but we had newspapers, radio, and newsreels. We knew the guys were storming beaches, taking hills against heavy machine-gun fire, getting shot down … too often in flames or over enemy territory.

We wanted to do our part. Help. Do what we could.

The posters helped us to know what that was, or how to do it better. And, no small thing, they made us feel that what we were doing was important. Was contributing to the war effort.

Victory Gardens, for example. Our soldiers were spread across the globe — formerly unknown islands in the Pacific, across North Africa, in Sicily, Italy, then Normandy, pushing into Belgium and Germany. If they were aboard ships or stationed at land bases, such as men in the Air Force, they had dining rooms or, if not actual cafeterias, first cousins to same. Take a tray and slide it down the chrome rails. But the food was hot and, if not Michelin 5 Star, good old American chow.

Not so the men on the front lines. They had meals-to-go. K-rations. Fresh, like hot, a faint memory.

If the demands of the battlefront took their toll on the cuisine, there was wholehearted, full-throated support by the military and those of us at home to ensure they lacked for nothing, despite the fact that the nation suddenly — with 16 million men off serving their country — had two families to feed.

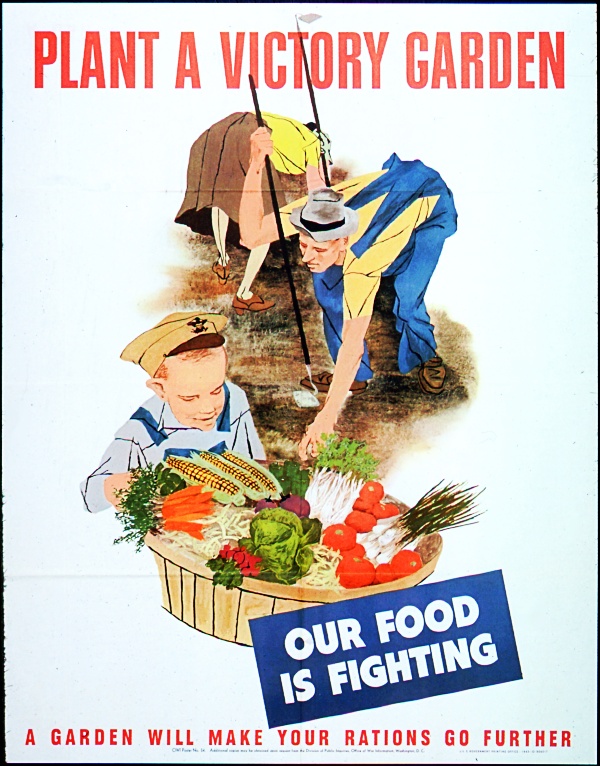

We were encouraged to plant gardens and grow our own food, or as much of it as we could. PLANT A VICTORY GARDEN was the headline over a drawing of the planting of seeds and a basket of vegetables.

And new emphasis was put on canning. A common practice at the time, partly to save money during The Great Depression, partly to store food from the summer for the winter. One of the posters shows a woman canning, with the slogan “AM I PROUD…I’m fighting famine by canning food at home”

My favorite, with apologies to Toulouse Lautrec and the Montmarte section of Paris, a poster showing a glass Mason jar with the label CAN CAN.

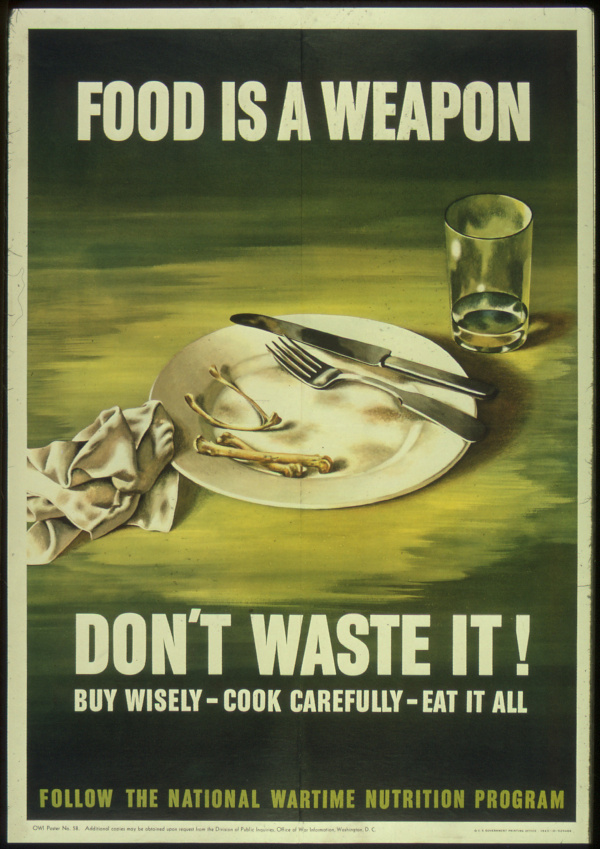

We were encouraged not to waste food. One poster showed a dinner plate, a knife and fork across it, the wishbone and drumsticks licked clean. The heading: FOOD IS A WEAPON. Beneath the illustration, DON’T WASTE IT! And beneath that: Buy Wisely – Cook Carefully – Eat It All.

Many such posters were linked to the rationing that was a big part of the war. We were each given a stapled booklet with stamps; when we went to the store to buy butter or sugar or meat, the grocer or butcher tore out the stamps to match the purchase. I remember the summer we had weekend guests and splurged on steaks. I was sent to the store to get them and remember the butcher tearing out the stamps from all three of the family’s books — Mother’s, Daddy’s and mine — for pretty much the rest of the month. I forget whether we then had to eat scrambled eggs or corned beef hash (canned).

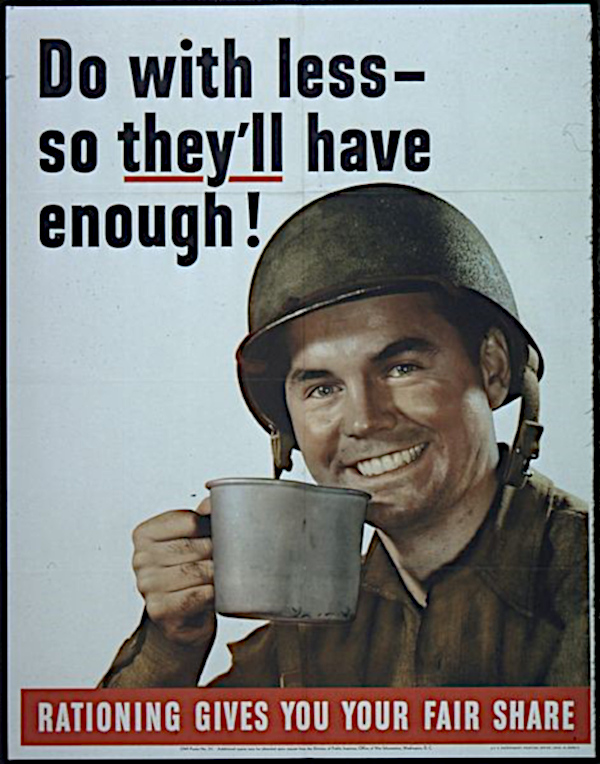

A number of posters linked the rationing to the troops. One had an illustration of a soldier holding a king-size tin cup for coffee, no doubt, with the slogan DO WITH LESS — SO THEY’LL HAVE ENOUGH.

Those 16 million men not only had to be fed, they had to be clothed. Fabric became an item to be restricted, if not rationed. Women’s skirts were suddenly straight (all pleats and fullness gone), just barely covering the knee. The cuffs on men’s trousers were sacrificed to the war effort. And a poster showed a mother mending a tear in the seat of her son’s pants as he bent over, illustrating the motto: USE IT UP – WEAR IT OUT – MAKE IT DO.

We were urged to save grease. We collected the excess fat and then took the containers to a designated site, so the glycerin in the fat could be used in making explosives. We also contributed to scrap metal drives, and saved rubber by driving less (gas rationing helped there).

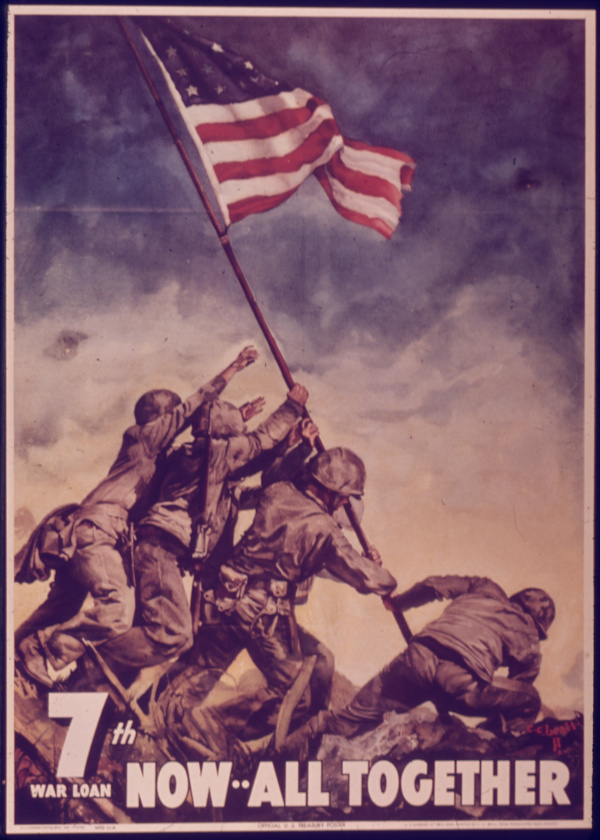

A principal goal of World War II posters was to boost sales of War Bonds, also called Victory Bonds. In the last year of the war the famed flag raising on Iwo Jima became background for the slogan NOW··ALL TOGETHER as a new War Bond drive was launched.

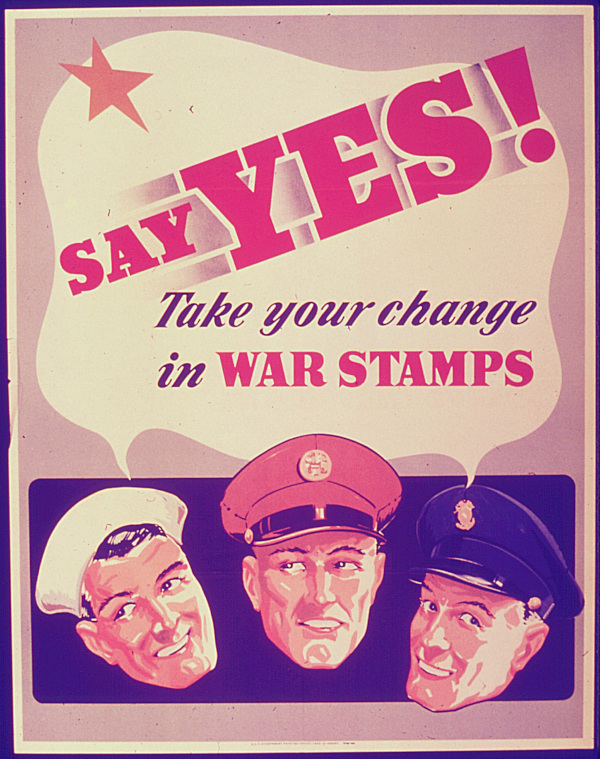

For those of us like me, a college student and then a copygirl at the Chicago Daily News, with a weekly salary of $15, there were war stamps. You bought them, not unlike postage stamps, and pasted them in a booklet. When you had enough for a bond — $18.75, as I recall — you turned in your stamps for the bond. (I never did cash mine in as the book was lost somewhere in the years of moving and growing up.) There was a poster for that, too. SAY YES! Take your change in WAR STAMPS. And the faces of three servicemen were lined up below, representing their respective services.

Whatever the message, the World War II posters are part of the war’s history. They were a big part of keeping up morale, financing the war, blending the rationing at home with the needs at the front. Sacrifice, as noted, on both fronts.

Sacrifice is the actual title of one of the posters.

It shows a father in uniform who has boarded the train that will take him back to his base and, eventually, no doubt overseas. As the train is about to pull out, he gives his young son, who has come to see him off, a hug.

Did he return? Almost 500,000 of the 16 million did not.

The ultimate sacrifice.

Featured image: National Archives

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I like the article, but really the “We Can Do It!” poster was not known until it was re-discovered in the 1980’s.

Tom

Wonderful article, and fascinating, because the reader senses the inspiriting effect that these posters must have had. They acknowledged desperate crisis, but at the same time, asserted implicitly that common sacrifice and a communal, essentially non – materialistic approach to life would get us through it all.

I think this view of things has a general, great appeal to the vast majority of people even today, but we’re postmodern: empty, lacking a sense of God, and of the preciousness of each other; driven by advertising and so heterogeneous, in fact, fractionated, that it’s hard for me to believe today’s Americans could adapt to it as readily as they did eighty years ago.

There is a Greek word, which I cannot remember now, which stands for the mysterious matter of nostalgia for a time one never knew, and I believe it accounts for most of the fascination, even longing, which these posters stir in us.

I hate to criticize the great Rockwell, a national treasure indeed, but my gosh, his Rosie looks like she’s been using anabolic steroids. I’ve always thought Rosie’s appeal was in the improbability, at least for those times, of a young American woman’s doing what had generally been thought men’s work. ( My mother was one of them. ) I qualify it with “generally” because there had been Rosies, though fewer in number, during World War I., and even during the War Between the States.

It’s obvious to me that the drowning man of the great “Someone Talked!” poster is pointing accusatorily at that unknown someone.

Ms. Lauder, you really continue to enlighten me and everyone who reads your first hand accounts of World War II as a woman who lived it then, and as a contemporary woman of today!

Most of us think of the Rosie the Riveter Post cover first when recalling a World War II image, or the ‘We Can Do It’ poster, but there were so many others that were really a matter of life and death. ‘Loose Lips Might Sink Ships’ and ‘Someone Talked’ showing the dire consequences.

Several of the posters were about frugality, sacrificing for the common good during that crucial time. Planting a victory garden, not wasting food, use it up-wear it out-make do, taking your change in war stamps. The bottom line was sacrificing, not ‘greed is good’. Look where THAT toxic mindset has us as a divided nation today!

In closing I wanted to say the Dick Williams ‘canning’ poster was not familiar to me as a World War II poster previously. Frankly I only knew the image as a brief moving image in the original 2004 opening sequence of ABC’s “Desperate Housewives”. Being the modern woman you are, you’re probably familiar with it. If not, you can find it on You Tube. NO television shows of today would have an elaborate, one minute opening like that. ‘DH’ itself in fact replaced it with a quick replacement after the 2nd season or so. I know you’ll like the images and the music.