This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

When we learn about women in the American Revolutionary era, from our elementary school classrooms to rest stops on the New Jersey Turnpike, the focus is on figures who contributed to the new nation’s iconic imagery: Betsy Ross and her design for the first American flag; Molly Pitcher and her presence on the battlefields that helped bring the nation into being. Far less present in our collective memories are figures like Annis Boudinot Stockton, whose home safeguarded vital Revolutionary documents and who challenged patriarchal stereotypes through her poetry; and Abigail Adams, who wrote to her husband John during his time with the Continental Congress that if he and his fellow framers did not “remember the ladies” in the “new Code of Laws” they were crafting, “we are determined to foment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.”

We better remember figures like Ross and Pitcher because they fit more easily into our celebratory patriotic narratives. In my new book, Of Thee I Sing: The Contested History of American Patriotism (available now through Rowman & Littlefield and March 15th everywhere), I trace the origins and legacy of such celebratory American figures, but also highlight other stories from across American history. The clearest alternative is what I call critical patriotism, the form expressed by figures like Stockton and Adams who critiqued the nation’s flaws and failures in order to help push America closer to its ideals.

American history is full of exemplary critical patriots who provide an inspiring legacy for our 21st century critical patriotism. For Women’s History Month, here are a handful of such critical patriots to commemorate:

1. Hannah Griffitts and “The Female Patriots” (1768)

Stockton and Adams’ contemporary, Griffitts was a Philadelphia Quaker who contributed dozens of poems to her cousin Milcah Martha Moore’s voluminous commonplace book. Her poem “The Female Patriots” links feminism to the era’s incipient Revolutionary patriotism particularly clearly, bemoaning men who “supinely asleep, & deprived of their Sight/Are stripped of their Freedom, and robbed of their Right,” and calling upon her fellow women to take up the mantle: “If the Sons (so degenerate) the Blessing despise/Let the Daughters of Liberty, nobly arise.”

2. Catharine Maria Sedgwick and Hope Leslie (1827)

In an Early Republic period defined by expansion and concurrent policies such as Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act, national narratives seemed to have no place for Native Americans. But the novelist and activist Sedgwick offered a different vision of that foundational American community, creating in her historical novel Hope Leslie a case for what she called (in the book’s preface) “their high-souled courage and patriotism.” And her character Magawisca, a young Pequot woman who narrates to an English audience her own account of the 1637 massacre at Mystic, offers a “new version of an old story,” what Sedgwick calls “putting the chisel in the hands of truth, and giving it to whom it belonged.”

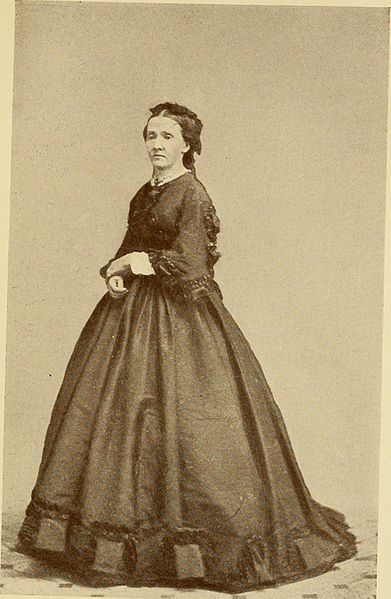

3. Julia Ward Howe and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” (1862)

Written as a marching song for Union soldiers during the Civil War, Howe’s military anthem could be seen as expressing celebratory patriotism. But the abolitionist activist Howe was initially inspired by the song “John Brown’s Body,” composer William Steffe’s abolitionist tribute to a man whose violent resistance to both slavery and the U.S. government itself comprised an extreme form of critical patriotism. And in her final verse, Howe presents a striking vision of the Civil War’s radical and righteous purpose, linking Jesus Christ’s sacrifice to the war’s goals of abolition and justice: “As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free.”

4. Ida B. Wells and The Reason Why (1893)

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago embodied celebratory patriotic visions of American greatness. And like too many of our national celebrations, it largely excluded Americans of color. In response, the journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells worked with colleagues (including Frederick Douglass) to produce and distribute on the exposition grounds the pamphlet The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition: The Afro-American’s Contribution to Columbian Literature. In the pamphlet’s final chapter, “The Reason Why,” Wells’s husband, the lawyer and activist Ferdinand Lee Barnett, expresses their hope that the text “will so inspire the Nation that in another great National endeavor the Colored American shall not plead for a place in vain.”

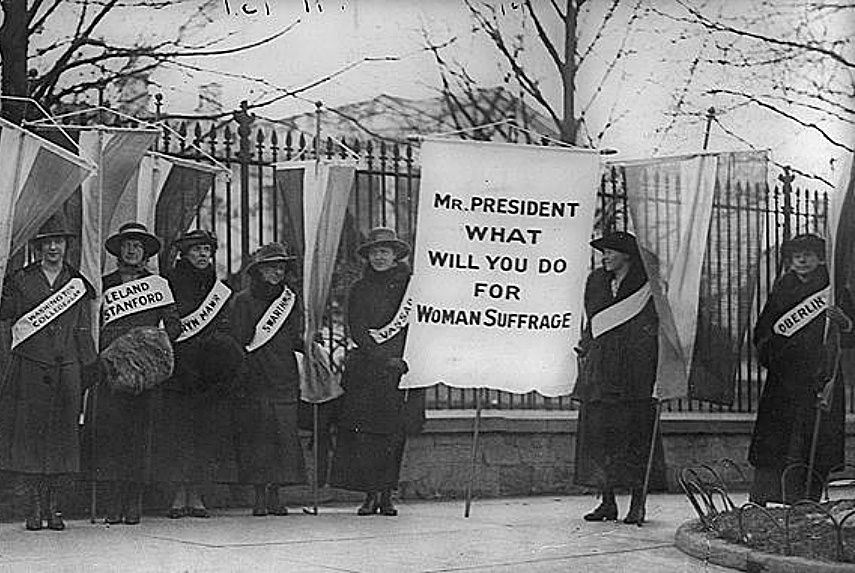

5. The Silent Sentinels

Over the last year, the nation has commemorated the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote. But sometimes lost in those celebrations have been the histories of radical, critical patriotic protest through which suffrage activists pushed the government and nation toward that groundbreaking amendment. A case in point were the Silent Sentinels, the suffrage activists who protested silently in Washington, D.C. for two-and-a-half years (between January 1917 and June 1919). They were met with official brutality and violence, including the horrific November 1917 “Night of Terror” in which more than 40 guards beat and arrested protesters in Virginia’s Occoquan Workhouse. But as a government physician noted of Alice Paul, one of the Sentinels’ leaders: she has “a spirit like Joan of Arc, and it is useless to try to change it. She will die but she will never give up.”

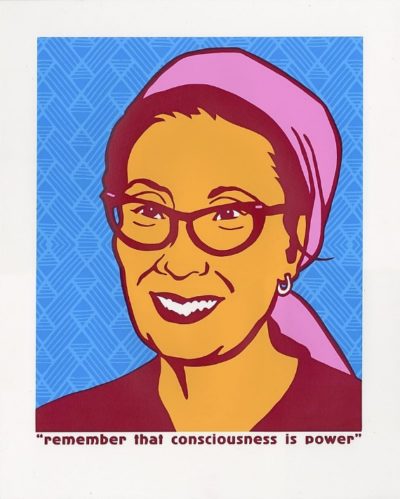

6. Yuri Kochiyama

The hundreds of thousands of Japanese Americans interned during World War II have exemplified patriotism on numerous levels, from the soldiers who volunteered for the army from internment camps to former internee George Takei’s contributions to the recent musical Allegiance (2012). One of the 20th century’s most impressive critical patriots was also a former internee: Yuri Kochiyama, who during the war helped her fellow interned young women write letters to Japanese-American soldiers and who went on to contribute to countless civil rights and activist movements, from leading the successful campaign for internment reparations to her friendship with Malcolm X and her solidarity with the Puerto Rican independence activists who occupied the Statue of Liberty in 1977. If, as Howard Zinn famously put it, dissent is the highest form of patriotism, no 20th century American embodied that form better than did Kochiyama.

Featured image: Silent Sentinels picketing the White House in 1917 (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

These are definitely all very remarkable American women. I appreciate the research and links you include here. Each and every one of these women in her own way and own style worked to make life better not just for women, but everyone.

Much has been written about the destructive divisions in the U.S., particularly over the past year. It starts at the top. With two dysfunctional political parties (one especially) working against the American people at any and every turn, it makes the January insurrection ironic.

How can I not feel our own government doesn’t want to exterminate the average American? We’re paying these people who are supposed to be “civil servants working for us”. The irony of the January 6th insurrection (which was awful on all levels) is that what they wanted to do the vice-president and so many others there, is what the government has already done to millions of our own citizens, and continue to do. All quietly, in suits and ties.

The insurrectionists put a realistic unvarnished look and sound to what our “leaders” are doing to us. I don’t know if you’ve ever noticed this Professor Railton, but no Democrats or Republicans EVER identify themselves as Americans. They’re Democrats and Republicans only. “Americans” are the people they look down on with everything from just not caring to disgust, to downright hatred. Not even trying to hide it! All America is to them is a country to rape and pillage for their own financial gain.

Until THIS situation is completely overhauled and fixed (I don’t see how) the divisions will continue to accelerate preventing any healing from ever happening. You can’t keep callously and viciously smothering most Americans financially without these problems continuing to get worse, be it racial and everything else. To turn things around would mean putting people first (like Canada and Europe) instead of Wall Street, corporate donors, the military keeping us in endless wars and more. Like I said, I can’t foresee that ever happening, but would love to be wrong.

PS. If folks are interested in buying the book, please feel free to email me ([email protected]) as I have a discount code for 30% off both the print and e-book versions. Thanks!

Ben