When you think of the iconic directors of horror movies, it’s usually male filmmakers like Wes Craven, George Romero, John Carpenter, Tobe Hooper, and David Cronenberg that come to mind. The best-known women in horror tend to be “scream queens,” actors like Fay Wray and Jamie Lee Curtis, whose characters are frequently relegated to perpetual victim status and who may be occasionally awarded the role of villain. But women are rarely talked about for their off-screen contributions to horror.

So it may come as a surprise — though it shouldn’t — to learn that women have always been at work behind the scenes, aiding in the development of the horror genre across numerous media. Milicent Patrick was the costume designer behind the Gill-man from Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954); Daphne du Maurier wrote the short story that Alfred Hitchcock adapted as The Birds (1963); TV horror hosts Maila Nurmi (Vampira) and Cassandra Peterson (Elvira) reshaped how audiences engage with horror films through the lens of camp and kitsch; Stephanie Rothman worked alongside B-movie legend Roger Corman for several years before going on to direct the cult horror exploitation film The Velvet Vampire in 1971. More recently, Nia DaCosta made history when Candyman (2021) became the first film directed by a Black woman to debut in first place at the box office, setting a vital precedent for the future of the horror genre.

Decades earlier, as we chronicle in our new book, Comic Book Women: Characters, Creators, and Culture in the Golden Age, women were also at the forefront of the horror genre. Between the 1920s and 1940s, pulp magazines, seen today as an ancestor of horror cinema and B movies as well as a direct precursor to comic books, emerged as the forum for fantasy, science fiction, and horror tales starring women in peril. While the bylines were dominated by male writers like H. P. Lovecraft and Robert Bloch, it was a woman who defined the aesthetic of one of the most influential pulp magazines during its most iconic and memorable era.

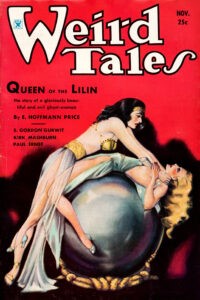

Margaret Brundage, who began her career as a fashion illustrator for various Chicagoland newspapers, began painting for Weird Tales in 1933. Initially hired by editor Farnsworth Wright to produce illustrations for the adventure pulp Oriental Stories, Brundage was soon tasked with providing cover art for Weird Tales, the more popular of the two Wright-helmed publications. In total, Brundage was responsible for 66 of the magazine’s cover illustrations between 1933 and 1945. She is the artist most associated with Weird Tales — and, arguably, the shudder pulp genre.

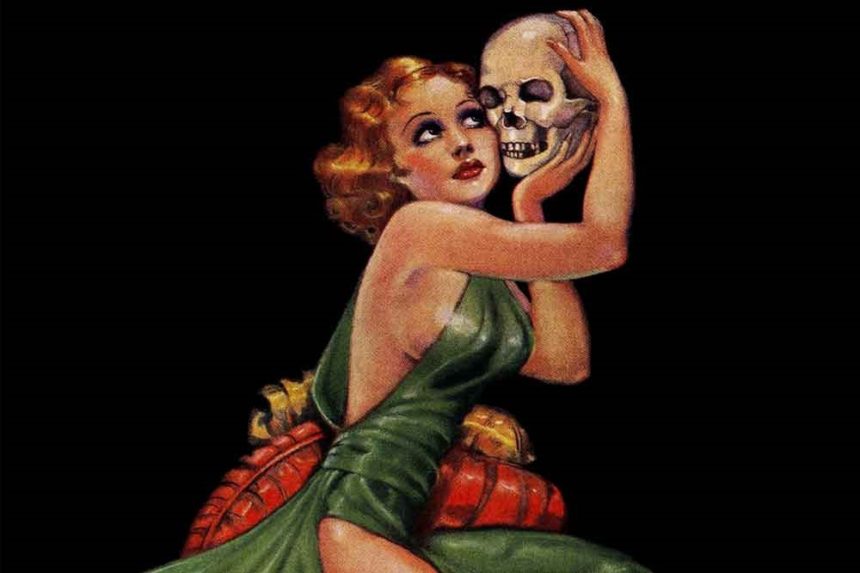

Beautiful women in danger were a favorite subject of Brundage, and the stories published in Weird Tales contained no shortage of damsels in distress to inspire her. While her painterly, colorful covers often feature nude women cowering as they were beaten, chained up, or pursued by some kind of beast; a key element of her style was that she depicted women as aggressors, as characters with power and control, in frequent, if not equal, measure. Her artwork was so popular with readers that authors sometimes wrote scenes into their stories in hopes of inspiring a Brundage-illustrated cover. Nevertheless, she was the one who bore the brunt of criticism for performing the very task that her job called for: depicting eroticized, violent scenes featuring beautiful women. H.P. Lovecraft himself criticized the sexual overtones of many of her cover illustrations as a cheap ploy by Weird Tales’ editors to attract a larger audience. In a letter to fellow sci-fi author Robert Bloch, Lovecraft called Brundage’s covers “irrelevant” and “even worse” than some of the fiction that appeared in the pages of pulp magazines, claiming not to understand the relevance of her work to the weird fiction genre.

Despite such criticism by others in her field for depicting women in vulnerable, erotically charged situations, Brundage never stopped — or paid much attention to naysayers. In a 1973 interview, Brundage commented that she had been asked by Weird Tales to “make larger and larger breasts…larger than [she] would have liked”; otherwise, she seems to not have taken much issue with the work assigned to her by the magazine. In fact, Brundage is alleged to be one of the few Weird Tales illustrators who took the time to read the magazine cover-to-cover, with her eyes peeled for scenes that would make for eye-catching cover art that aligned with her style and interests. Brundage’s legacy as a figure in the history of the horror genre goes far beyond her cover illustrations for Weird Tales, though; as a woman artist who openly created sexually charged, violent works, she paved the way for women with untraditional, perhaps “indecent” perspectives to find homes for their work in the developing horror comics genre.

Brundage is just one of a number of women creators who helped develop the horror genre. June Tarpé Mills was another pioneer, but she had to drop her first name when signing her work in order to create a masculine sounding pen name. Best known for creating the early female action hero Miss Fury (who some argue is the first female superhero), she also created “The Purple Zombie,” one of the earliest ongoing horror characters in comics. Mills’s horror resume also includes “The Vampire” and “The Ivy Menace,” two horror tales that appeared during the late 1930s, well before horror comics gained widespread popularity. “The Vampire” even included a twist ending—an uncommon device for comics at the time, but which became a staple of EC horror comics by the 1950s and in cinema decades later.

EC Comics dominated the horror genre with such well-remembered series as Tales from the Crypt and The Vault of Horror, but it’s thanks to artist Lily Renée that horror comics gained new ground. Renée worked on “The Werewolf Hunter” between 1943 and 1948, creating plot ideas and drawing all manner of supernatural terrors for stories that regularly featured powerful female villains in relatively empowered roles for the era. EC’s distinctive touch was also thanks to Marie Severin, EC’s lone female creator. The colorist for the publisher’s gory, gruesome images, she had a substantial influence on the publishing house. Severin was a pioneer of the genre, often using dark color palettes to define the aesthetic of the most popular horror comics of all time. By obscuring the ghastliest panels with shadowy tones, EC could get away with publishing its most shocking content.

These women are just a few examples of genre pioneers who today have been largely neglected by modern fans because of the male-dominated way in which comic book history has been told. In more recent years, it’s become much easier to identify the contributions women creators are actively making to the horror genre, thanks to the work of directors like Nia DaCosta, Kathryn Bigelow (Near Dark), Mary Lambert (Pet Cemetery), Mary Harron (American Psycho) and Jennifer Kent (The Babadook), and novelists like Anne Rice (Interview with the Vampire) and Alma Katsu (The Hunger). Horror comics are also experiencing a renaissance thanks to the award-winning work of Emil Ferris (My Favorite Thing Is Monsters) and Marjorie Liu (Monstress).

Still, to hear some tell it, horror isn’t a genre that women are interested in. A few years ago, contemporary horror hitmaker Jason Blum caught flack for denying that there were any — or enough — women who wanted to direct horror movies, though he insisted he was “always trying” to find one. As Blum’s comments demonstrate, when it comes to the horror genre, women continue to be thought of as victims first and foremost. But with respect to scream queens like Jamie Lee Curtis — whose latest entry in the Halloween franchise opened this month — we must not forget that women have been in horror from the beginning, using the genre as a forum to have their voice heard in ways that are louder and more resonant than the visceral scream.

Peyton Brunet is a writer and ceramicist living in Chicago, Illinois. She is a graduate of DePaul University’s Communication and Media graduate program.

Blair Davis is an associate professor of Media and Cinema Studies at DePaul University in Chicago. He is the author of such books as Comic Book Movies, Movie Comics: Page to Screen/Screen to Page, and The Battle for the Bs: 1950s Hollywood and the Rebirth of Low-Budget Cinema.

Originally published on Zócalo Public Square. Primary Editor: Jackie Mansky | Secondary Editor: Gabrielle Bruney

Featured image: Detail from a Margaret Brundage Weird Tales magazine cover from November 1933 ( Flickr CC BY 2.0 /Lawren)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

There were plenty of female writers for the horror/sci-fi magazines, who hid their gender behind asexual sounding names. C. L. (Catherine) Moore and Leigh Brackett (who wrote the first draft of the screenplay for “The Empire Strikes Back.” The film was dedicated to her memory. Oh, and as for Weird Tales covers: regular contributor Seabury Quinn always included a woman in peril in his stories so he would get a cover illustration!

That opening shot by Margaret Brundage from November 1933 looks like the breasts were pretty close to maxed-out then, and they wanted her to make them larger, per that interview? Good grief! They would have been as big as Candy Samples. The November ’34 cover is something else too. Most of all? This entire article, Ms. Brunet.