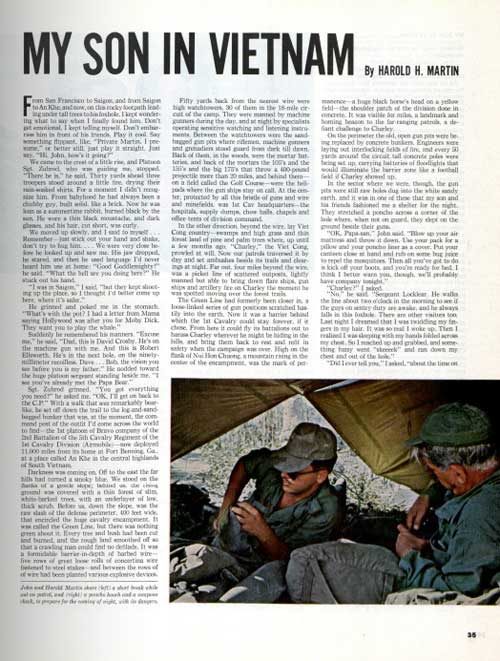

Heroes of Vietnam: My Son, the Soldier

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

—This article is excerpted from “My Son in Vietnam” by Harold H. Martin, originally published July 16, 1966, in the Post. The complete story as it appears in the original magazine is available at the end of this article. —

From San Francisco to Saigon, and from Saigon to An Khê, and now, on this rocky footpath leading under tall trees to his foxhole, I kept wondering what to say when I finally found him. Don’t get emotional, I kept telling myself. Don’t embarrass him in front of his friends. Play it cool. Say something flippant, like, “Private Martin, I presume,” or better still, just play it straight. Just say, “Hi, John, how’s it going?”

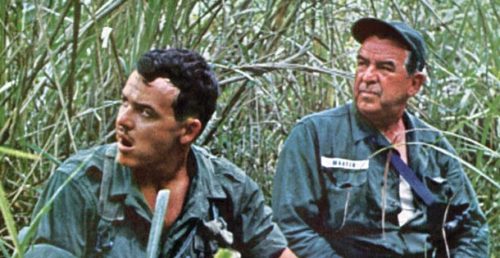

We came to the crest of a little rise, and Platoon Sgt. Zubrod, who was guiding me, stopped. “There he is,” he said. Thirty yards ahead, three troopers stood around a little fire, drying their rain-soaked shirts. For a moment I didn’t recognize him. From babyhood he had always been a chubby guy, built solid, like a brick. Now he was lean as a summertime rabbit, burned black by the sun. He wore a thin black moustache and dark glasses, and his hair, cut short, was curly.

We were very close before he looked up and saw me. “Good Goddlemighty!” he said. “What the hell are you doing here?” He stuck out his hand.

“I was in Saigon,” I said, “but they kept shooting up the place, so I thought I’d better come up here, where it’s safer.”

He grinned and poked me in the stomach. “What’s with the pot? I had a letter from Mama saying Hollywood was after you for Moby-Dick. They want you to play the whale.”

Suddenly he remembered his manners. “Excuse me,” he said. “Dad, this is David Crosby. He’s on the machine gun with me. And this is Robert Ellsworth. He’s in the next hole, on the 90 mm recoilless. Dave … Bob, the vision you see before you is my father.” He nodded toward the huge platoon sergeant standing beside me. “I see you’ve already met the Papa Bear.”

Sgt. Zubrod grinned. “You got everything you need?” he asked me. “Okay, I’ll get on back to the C.P.” With a walk that was remarkably bearlike, he set off down the trail to the log-and-sand-bagged bunker that was, at the moment, the command post of the outfit I’d come across the world to find — the 1st Platoon of Bravo Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) — now deployed 11,000 miles from its home at Fort Benning, Georgia, at a place called An Khê in the central highlands of South Vietnam.

Darkness was coming. We stood on the flanks of a gentle slope; behind us, the rising ground was covered with a thin forest of slim, white-barked trees, with an underlayer of low, thick scrub. Before us, down the slope, was the raw slash of the defense perimeter, 400 feet wide, that encircled the huge cavalry encampment. It was called the Green Line, but there was nothing green about it. Every tree and bush had been cut and burned, and the rough land smoothed off so a crawling man could find no defilade. It was a formidable barrier-in-depth of barbed wire — five rows of great loose rolls of concertina wire fastened to stakes — and between the rows of wire had been planted various explosive devices.

Fifty yards back from the nearest wire were high watchtowers, 30 of them in the 18-mile circuit of the camp. They were manned by machine gunners during the day, and at night by specialists operating sensitive watching and listening instruments. Between the watchtowers were the sandbagged gun pits where riflemen, machine gunners, and grenadiers stood guard from dark till dawn. Back of them, in the woods, were the mortar batteries, and back of the mortars the 105s and the 155s and the big 175s that throw a 400-pound projectile more than 20 miles, and behind them — on a field called the Golf Course — were the helipads where the gun ships stay on call. At the center, protected by all this bristle of guns and wire and minefields, was 1st Cav headquarters — the hospitals, supply dumps, chow halls, chapels, and office tents of division command.

In the other direction, beyond the wire, lay Viet Cong country — swamps and high grass and thin forest land of pine and palm trees where, until a few months ago, “Charley,” the Viet Cong, prowled at will. Now our patrols traversed it by day and set ambushes beside its trails and clearings at night. Far out, 4 miles beyond the wire, was a picket line of scattered outposts, lightly manned but able to bring down flare ships, gun ships, and artillery fire on Charley the moment he was spotted.

The Green Line was a barrier behind which the 1st Cavalry could stay forever, if it chose. From here it could fly its battalions out to harass Charley wherever he might be hiding in the hills, and bring them back to rest and refit in safety. High on the flank of Nui Hon Chu’o’ng, a mountain rising in the center of the encampment, was the mark of permanence — a huge black horse’s head on a yellow field — the shoulder patch of the division done in concrete. It was visible for miles, a defiant challenge to Charley.

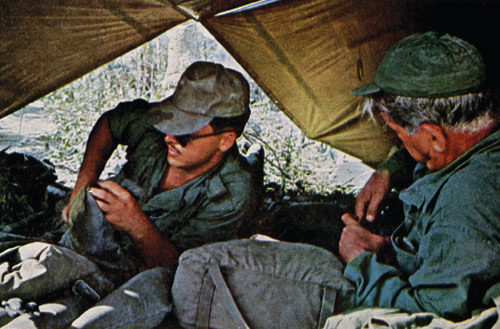

In the sector where we were, the gun pits were still raw holes dug into the white sandy earth, and it was in one of these that my son and his friends fashioned me a shelter for the night. They stretched a poncho across a corner of the hole where, when not on guard, they slept on the ground beside their guns.

“Okay, Papa-san,” John said. “Blow up your air mattress and throw it down. Use your pack for a pillow and your poncho liner as a cover. Put your canteen close at hand and rub on some bug juice to repel the mosquitoes. Then all you’ve got to do is kick off your boots, and you’re ready for bed. I think I better warn you, though, we’ll probably have company tonight.”

“Charley?” I asked.

“No,” he said, “Sergeant Locklear. He walks the line about two o’clock in the morning to see if the guys on sentry duty are awake, and he always falls in this foxhole. There are other visitors too. Last night I dreamed that I was twiddling my fingers in my hair. It was so real I woke up. Then I realized I was sleeping with my hands folded across my chest. So I reached up and grabbed, and something fuzzy went ‘skeeeek’ and ran down my chest and out of the hole.”

“Did I ever tell you,” I asked, “about the time on Okinawa when the rats ate Captain Buchanan’s moustache?”

“Yes,” he said, “you told me.”

“It just goes to show,” I said, “that down on the rifleman’s level, wars don’t change very much.”

All up and down the defensive line, though, as the platoon got ready for night, it was evident that this war had changed from anything I remembered. In a cleared place in front of the platoon C.P., helicopters were whirring in, dropping their loads of weary, sweat-soaked troopers. They’d been out all day, John explained, working out a new way of dropping men in rough terrain. Before, they had been going into clearings, or open paddies in the valleys. In forest country, these clearings were rare, and Charley had rigged them with booby traps and encircled them with guns.

“It makes for a pretty hairy operation,” John said. “The choppers go in low and flare out over the drop zone. If the drop zone’s full of logs and brush and downed trees, you have to jump from the chopper while it’s hovering maybe 6, 8 feet off the ground, and with all the gear you are carrying, you hit with a hell of a thump. Being the machine gunner, I’m the first out, and as I jump out, I feel the chopper begin to lift. Sometimes the ammo bearer, who is the third guy out, jumps from a chopper that’s already 12 feet in the air. He hits like a watermelon rolling off a kitchen table.

“Since there’s a good chance Charley’s got a welcoming committee waiting, there’s always a lot of shooting before we get there,” he said. “The artillery’s first. Then the gun ships go in with rockets to beat up the brush around the drop zone, and the gunners in the choppers are firing as they come in. Sometimes, when the landing zone is too rough, we go down rope ladders, but this takes longer and the chopper pilots sweat it. It keeps them in the area too long.”

The newest technique, he explained, gives an airmobile outfit a great deal more flexibility in its assault landings. The choppers now hover over the forested hilltops, and the troops slide down into and through the tree canopy on long nylon ropes, using the same rappelling technique which enables mountain climbers to bounce down the sides of steep cliffs. This frustrates Charley, who can’t guard every hilltop in the highlands.

It was nearly dark as the last helicopter landed. John brought his machine gun down from the tower to set it up for the night. A slow drizzle began to fall as he set up the gun. Fascinated, I watched him, a stranger to me now — a professional working at his trade.

Through the drizzle a slim, blue-eyed sergeant appeared, trailing a thin wire behind him. Beside the gun he laid a rubber-covered device that looked like a hand stapler. John introduced us. “Sergeant Richardson has been out in the wire, arming the claymores,” he explained. Richardson reached into a sandbag and pulled out a putty-colored curved device, the size and shape of the back of a stenographer’s chair. “It’s a plastic explosive,” he said, “with little lead balls imbedded in it. You can burn it, shoot it, stomp it, or drop it and it won’t do anything. It takes an electric charge to set it off. That’s what this thing here is for. It’s the detonator. You attach it to this wire that leads to the claymore and squeeze it, and blam — old Charley gets his butt full of marbles.”

Off to the east, a bright star suddenly blazed in the sky, hung for a moment, and began a slow descent, silhouetting the distant hills.

“Flares,” John said. “Somebody out on the picket line thought he saw something, or heard something, so he asked for some light. You see that gap over there? The highway from here to Pleiku runs through it. Charley loves to set ambushes there. And we love to set ambushes for Charley there. So nearly every night there’s a lot of shooting in the pass.”

A shadow loomed above the hole.

“How many fillers you need?” a voice said.

“Three,” John said.

“You get two,” the voice said. Then, in a hoarse whisper, “the password’s ‘Coffee — Song.’”

The big shadow moved away, leaving two smaller shadows standing in its place. They were the “fillers” — clerk-typists from the artillery batteries who pulled guard duty on the barrier line with the shorthanded rifle platoons.

I stood the first watch with John. We talked in low tones, while behind us the mortars coughed and the howitzers banged, and the deep explosions shook the hills. I remembered the decision that had brought him here.

“I guess that answers a question I was supposed to ask you,” I said. “About how you’d feel about transferring out of this outfit. I know a guy …” I stopped, and there was a long silence.

“No,” he said. “Leave it alone. I appreciate it. But I trained with these guys, and I came over here with ’em, and I fought Charley with ’em. I was in the hospital with a bunch of them. So I think I’ll see this through … with these same guys … as long as I’ve got to stay over here.”

I asked him how long that was, and he said he didn’t know for sure. The tour was a year, and every man can tell you, to the day, how much of the year he still has to serve. But, John told me, there was a big fat rumor going around that, for the guys who had been in combat, it was going to be cut to 10 months. “If that’s true,” he said, and you could hear the hope in his voice, “I’ve got it made. My tour started the day I cleared San Francisco — November 28, 1965.”

The length of his tour is about the only facet of U.S. policy that profoundly concerns the foxhole soldier. He does not waste time philosophizing about whether this is a just war or not. He’s in it, and there’s nothing he can do about it but fight, and survive if possible.

“What do you think about when you are standing guard out here?” I asked.

“Home mostly,” he said. “Wondering if the reality of getting back will be anywhere near as good as the dream.”

We talked on. He seemed to feel not anger, but a pitying contempt for the anti-war demonstrators. “People say they ought to be drafted and sent over here,” he said. “We don’t want ’em. Nobody would want to go into combat having to depend on one of those guys.”

“Actually,” he said, “I’ve got more respect for Charley than I have for those people. At least Charley will fight, and when you think about what he’s got to fight with, you wonder how he keeps resisting. No air, no real artillery except anti-aircraft weapons, nothing but small arms and a few mortars. No way to get about except on his two flat feet, wrapped in old tire retreads.”

“The time your platoon got ambushed — was there anything you didn’t tell us?”

“Not much,” he said. “We came down off the ridge into a dry paddy, and Charley let loose. I got zapped in the leg and crawled down a ditch toward a big water-filled hole where old Papa Bear was assembling the wounded. I found another guy in the tall grass and pulled him along. We finally got air strikes in there, and they smashed Charley, and the medevac choppers came in and lifted us out.”

By now it was 11:15. John moved off in the black dark to wake the artilleryman who would take over the guard.

Dawn came like a Chinese painting, with a gray mist drifting in the hollows of the distant hills. David Crosby, who had the last watch, went out to disarm the claymores, and the men of the night patrol, their green fatigues black with rain, came home through the mists like tired ghosts.

At the end of the company street, John peeled off the muddy, sweat-stained greens he’d been sleeping in for a week and stepped under the thin warm trickle of the improvised shower. Just above the knee, on the side of his left leg, I saw the long, red scar where the bullet had gone in, traveling upward through the thigh muscle. Just below the hip joint was a longer scar where the doctors had cut the bullet out.

“Judas Priest!” I said. “You did get zapped.”

“Yeah,” he said. “Next time it’s my turn.” He soaped happily. “Don’t get the idea, though, that I’m thirsty for revenge. If I never see Charley again, it’ll suit me fine.”

Late that night the platoon got the word that it had been looking forward to, half in eagerness, half in dread. The safe, but boring, days were over. The 2nd Brigade, to which the battalion was attached, was leaving the Green Line. The next morning, Bravo Company would move out on a 10-day search- and-destroy operation in country somewhere north of Pleiku.

“‘Search and destroy’ is like killing sharks in the Gulf Stream,” a trooper from Florida said. “You chum some bait and throw it overboard, and when the shark comes around, you shoot him. But he usually gets a bite or two of the bait before you kill him.”

In these operations the infantry serves as bait. Since Charley is essentially a guerrilla, he will not do battle unless he is sure he has the advantage. To tempt him to show himself, therefore, the searching units are small. When he does reveal his position, the world falls in on him. Planes and helicopters roar in with napalm and rockets, and artillery pounds him mercilessly. The Viet Cong dead may number 40, 50, 100, or more. American losses will be described as “light” or “moderate,” which they well may be in terms of the division, the regiment, or the battalion engaged. But the squad or the platoon which ran into Charley in the first place may have been pretty well wiped out. The planes and choppers don’t always get there quick enough.

On the night before the operation, Capt. William A. Taylor, commander of Bravo Company, called his platoon leaders to his tent to brief them on their mission. The area the brigade would be going into, he said, was supposed to contain a corps headquarters, protected by at least a company — perhaps by a battalion — of Viet Cong. There were Montagnard villages throughout the area, he said. They were fortified and believed to be unfriendly.

“But,” he added, “remember this when you check out the villages — DO NOT FIRE UNLESS YOU ARE FIRED UPON. I repeat: Do not fire on any village unless you get fire from there.

“Another thing,” the captain went on. “There will be no fraternization. Nobody will go into a native hooch for any purpose except to check it out.”

It was almost midnight before the briefing ended. In the BOQ tent, Lt. Keith Sherman, age 23, commander of the 1st Platoon, sat down to write his wife a letter. Down the company street the word of the company’s mission had spread fast. From the squad tent where John slept came the sound of singing. As I came into the tent, John looked up and saw me. “Come in, Papa-san,” he said jovially, making room for me on the bunk. “Sit down.” He took the canteen cup from another trooper and handed it to me.

The gulf that lies between the generations betrayed me. “You better get yourself physically prepared,” I said. “Why don’t you guys knock off the yodeling and get some sleep?”

There was a sudden silence. In the dim light of the candle, they looked very young, but they were not children to be scolded and sent to bed. I tried to cover up. I stood up and pretended to yawn. “Sorry,” I said, “I keep forgetting that you guys are about 30 years younger than I am. At your age you don’t need sleep.”

He followed me as I went out into the company street. We stood there for a moment in the dark. Finally, “Look, Dad — about tomorrow,” he said. “Patrolling off the Green Line is one thing — that country around there is pretty well secure. Tomorrow will be different. We’ll be in Viet Cong country. And if you get in tall grass and lose the man in front of you —”

“I get the message,” I said, “but don’t worry. I didn’t come out here to try to fight the war with you. I’m not that stupid. I wanted to try to tell the people back home how the plain old dog-faced, dragtailed, dead-eyed, bone-tired, foxhole soldier lives as he fights this war.

“So, about tomorrow — don’t sweat it. I’ll make the assault landing with you. Then I’ll stay in the landing zone while you guys strike out through the boondocks. And unless something comes up, I’ll leave you tomorrow night.”

I thought, when he said good night, that he sounded relieved.

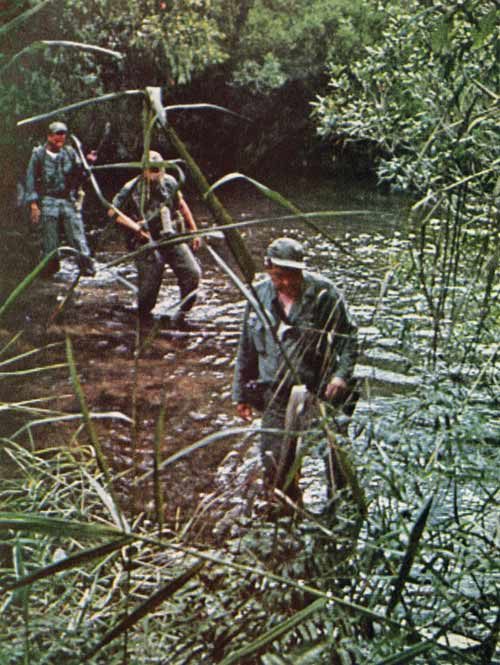

Morning came early. To a chorus of birdsong, the company moved out along a rocky road to the field where the helicopters waited. Climbing aboard, the troopers fell strangely tense and silent. There was no wisecracking, no horseplay. For many of them this was their first operation. For others, including John, it was the first since the ambush at Bông So’n had decimated the 1st platoon. Out of 37 men, two had been killed and 24 wounded; of the wounded, John and eight others had returned to duty. Silently they climbed in, settled back against the bright-red nylon web of the backrests, dropped their chins on their chests, and went to sleep.

There was a roar and a blast of blessedly cool air as the choppers lifted. In the open ports, machine gunners hung on their safety straps, watching the ground below.

I stood up and peered over the chopper pilot’s shoulder. Soon below us we saw the gun ships swimming back to base. Ahead was the landing zone they had just finished pounding. Dust and smoke rose from it, and there was fire in the brush, for the preparation had been thorough. Artillery, fixed-wing planes, helicopters, each in turn had pounded it. Now, as the gun ships pulled away, the lift ships roared in. We flared out, touched down, and the troopers poured out the back of the Chinook and landed running, headed for the brush. The chopper lifted and was gone. And all at once I was alone in an open field, in an eerie silence.

I headed for the bushes to the east of the field. Soon I saw men with weapons moving ahead of me in the thicket. The battalion sergeant major came up. The colonel was asking about me, he said. I followed him to where Lt. Col. E.C. Myers, the battalion commander, was making a quick check of the area. Back with troops after a tour in the Pentagon, he had the look of a happy man. Nearby there was the muffled boom of an explosion and a billow of yellow smoke. The troops, moving through the brush, were tossing smoke bombs into the openings of a network of tunnels. When the smoke cleared, he said, men would go in to check them out. But they looked as if they had been abandoned. Everywhere, in the open field where we landed, there were square holes, hip-deep, dug in the red earth, and in the bottom of these holes, sharpened bamboo stakes had been set in place. But the holes had not been covered over with the thin covering of twigs, earth, grass, and leaves that would turn them into deadly traps. Charley, it was obvious, had recently been here, and in considerable numbers. But he had gone.

“Souvenir,” he said. “Take it home for me, please, and hang it on the wall in my room.”

Pretty soon there was nothing else for us to talk about.

“Well, so long,” I said. “I’ll be seeing you around Christmas, I guess.”

“I hope so,” he said. “Give mother my love.”

“I will.” I stood there a minute, trying to think of something else to say. “You guys take care of each other, David,” I told his friend.

“We’ve done it so far,” Crosby said. “We’ll keep on.”

As the chopper soared up, heading for Pleiku, I saw among the shattered trees below the raw earth of a new foxhole. A trooper was standing beside it. It might have been him. I couldn’t be sure, for it was getting dark and beginning to rain. He, or one of his buddies, it didn’t matter. They are all good men.

Postscript: John Martin made it home safely the following year and finished out his military career with distinction, training new recruits for their own tours in Vietnam.

—“My Son in Vietnam,” July 16, 1966

Therapy Dogs and Healing

The small shapes lay motionless, each cocooned in a protective sheath of wires and tubing as a team of nurses ministered to their needs. On this day, the pediatric intensive care unit at UCLA Medical Center was filled to capacity. Above the low hum of voices and the occasional squeak of a rubber shoe on polished floors floated the hypnotizing bleeps of monitoring equipment. A blue fluorescent light washed over everything and seemed to magnify the smallest detail—a few drops of blood here, a splash of yellow fluid there, the pale skin of a seriously ill child farther on. Parents hovered in corners, not wanting to get in the way, but fearful to leave.

Into this sanctum stepped Laura Berton-Botfeld with her therapy dog—a 70-lb blond poodle named Apollo. The father of one of the patients spotted them and came quickly to her side. “Over here,” he said, tugging on her arm. Laura and Apollo moved to the bed of his 10-year-old daughter, whom we’ll call Sophia to protect her privacy. The delicate, wan figure under the sheets had bacterial meningitis—an inflammation of the brain that can be fatal. By the time Laura and Apollo arrived, the girl had been in a coma for seven days, and things were not looking good. Doctors had told the parents to prepare for the worst.

Sophia’s dad propped his daughter up with pillows. Her unseeing eyes were wide open, a beautiful blue, framed by lank blond hair.

Normally, with a patient’s permission, Laura has Apollo jump up on a chair beside the bed then onto the bed itself. He’s trained to sit with his broad back to patients so they can stroke him and nestle their fingers in his fur. In this case, because Sophia was not conscious, Laura urged Apollo only to sit on the chair, a position that left him practically nose to nose with the patient. “It was the weirdest thing,” says Laura. “Sophia’s eyes seemed to just lock onto Apollo’s, and the dog’s gaze was so intense I thought he was going to kiss her—something therapy dogs are trained not to do.”

Eventually, Laura moved Apollo to the foot of the bed where he continued to watch the patient intently with his intelligent, poodle eyes for a good 20 minutes. But Sophia was unresponsive, and eventually Laura and Apollo moved on to other patients. A few hours later as she sat in a parking lot waiting to pick her daughter up from school, Laura’s phone rang. It was Jack Barron, director of UCLA’s People Animal Connection (PAC), the volunteer organization responsible for Laura, Apollo, and 49 other therapy-dog teams at UCLA.

“He said, ‘Sophia just woke up,’” recalls Laura. “‘And her first words were, “Where’s Apollo?” How fast can you get back here?’”

In hospitals across the country, stories like Laura’s are common. “I see miracles here every day,” says Barron as he talks about the PAC program in the medical center’s cafeteria. “People who just wake up. People who start eating. People who finally take their meds. People who are paralyzed and then suddenly move a couple of fingers to wave at a dog.”

But if the healing associated with these dog visits is stunning, so are the sheer numbers of dogs and their humans now certified to provide Animal Assisted Therapy (AAT), the technical term that refers to using trained dogs intentionally as a therapeutic healing tool. The Delta Society, a non-profit organization that evaluates and certifies teams across the U.S., has gone from 700 AAT teams to a staggering 10,000 plus in less than 20 years while Therapy Dogs International, a non-profit that also credentials dogs, reports that it has fielded 20,000 teams in the U.S. and Canada.

Although dogs have been used for therapeutic purposes around the globe for years, today, particularly in the U.S., their use is driven by mounting evidence that dogs truly can heal. One look at a therapy dog strolling into a hospital room and a patient’s blood pressure drops, heart rate slows, and the corrosive hormones generated by stress that damage arteries and play a part in so many diseases and disorders plummet.

In a study at the University of Southern Maine researchers found that therapy dog visits calmed the agitation of patients with severe dementia. At UCLA another group of researchers found that therapy dog visits had a significant effect on heart patients. The study looked at 76 patients with heart failure and their responses to a 12-minute visit from either a therapy dog or a volunteer, then used blood tests to compare the patients’ responses to other patients who had no visit of any kind. The results were unequivocal: There were essentially no changes in those who did not receive a visit. Visits from volunteers lowered anxiety levels around 10 percent, and didn’t do much else. But visits from therapy dogs reduced pressure in the heart and lungs by 10 percent, reduced stress hormones by 17 percent, and lowered anxiety levels by a startling 24 percent. A similar study at Massachusetts General Hospital supported those results and extended them. In this report, visits from therapy dogs markedly reduced patients’ pain levels as well.

“Blood levels of endorphins generated by the body increase dramatically after dog visits,” says University of Pittsburgh neurologist and pain specialist Dawn Marcus, M.D., author of The Power of Wagging Tails. “That’s why pain levels go down. Endorphins block stress chemicals—the body’s natural narcotic.”

Nor are the physiological effects of a therapy dog visit fleeting. Other studies have found that the benefits last a full 45 minutes. “It’s not just that the dog walks in and does its stuff,” says Marcus. “Even very brief encounters produce a helpful effect. There’s a profound, biological change. And the change is associated with better health. So when you see changes in someone who connects with a therapy dog, something’s really behind it. We’re not just crazy dog nuts. Real science proves the dogs make a difference.”

To get a sense of just how therapy dogs work their magic, this reporter pays a visit to the UCLA medical center early one morning where I meet Charley, a personable, 79-pound “goldendoodle” (golden retriever/poodle mix) therapy dog and his handler, Ellen Morrow.

It takes me about two seconds to fall in love with them both. Charley has long, straight, creamy-beige fur that falls in shaggy lines from the top of his huge head to the bottom of his equally huge feet—and a sparkle in his eyes that suggests he’s up for anything. At the other end of his leash—complete with ID badge and carrying a navy cloth bag stuffed with everything from treats and collapsible water bowls to doggie-wipes, balls, biobags, hand sanitizer, and a brush—his teammate Ellen is a tiny powerhouse of positive energy with hair about the same color and cut as Charley’s.

The three of us take the elevator up to the 4th floor to visit the adolescent psych unit. There, on an outdoor triangular roof patio sheltered on two sides by the medical center and on a third by 20-foot, clear, shatter-proof panels, a dozen kids between 14 and 18 are gathered in the sun. Some lounge in twos and threes on benches, others pace back and forth, and a few simply wander around. One kid stands alone up against a wall, looking down at his feet, shifting his weight back and forth from one foot to the other. Tall and thin, with creamy café-au-lait skin and beautiful dark curls, he is completely withdrawn, isolated as if alone on a desert island.

Except for this one young man, the kids light up when they see Charley. Ellen calls out, “Do you want to see Charley do some tricks?” and the patients gather around the two, petting the dog, shaking his paw, answering Ellen’s questions about their own pets, and asking questions about Charley. Eventually they perch on benches while Ellen folds her legs under her and sits on the ground, nose to nose with Charley.

She puts Charley through his paces—speaking in his regular voice, his quiet hospital voice, his big voice, and finding a circular cut-out on the ground as kids shift it around. But his big crowd-pleaser is the way he shakes hands, literally curling his paw around the kids’ hands and squeezing. “It’s like he’s holding your hand,” chuckles Ellen. “It’s a very personal connection. They just light up!”

The kids bond instantly with the dog. As Ellen draws kids, dogs, even staff into the interaction, each begins to open to the other: kids to dog, then to Ellen, then to staff. The process is beautiful to watch.

But the quiet young man by the wall never looks up.

Then something happens. Ellen asks Charley to give her a high-five, and the dog joyfully leaps straight up into the air, smacking both of Ellen’s raised hands with his shaggy front paws.

The kids squeal with delight, and suddenly the silent young man is paying attention. His eyes come into focus and he stops rocking back and forth. A few minutes later he rigidly stretches out a hand in Charley’s direction. Ellen, seeing the invitation, moves the dog closer. For the next 10 minutes, the young man is anchored to reality by a shaggy dog.

In the psychiatric world, breakthroughs are often made from far less.

“I love these dogs,” says unit nurse Coleen Moran. “They know when someone needs love. And that’s better than any medicine.”

Charley, Ellen, and I walk down another corridor toward the neuro trauma unit where Charley and Ellen are scheduled to visit Lois Kearney who recently had a stroke. When we arrive on the otherwise sunny unit, Lois’ room is pitch dark except for the red, white, and green lights of monitors measuring every sign of life.

Ellen checks with a nurse to see what’s going on. The nurse enters the room and quietly asks Lois if she’d like to see Charley. “Oh yes,” a faint voice murmurs from the bed.

“Come on in,” the nurse calls as she opens blackout drapes and flips on some lights.

Lois is sitting propped up on a high bed, wires taped to her head and neck, a tube taped to her nose, an oxygen mask dangling to her shoulder, IVs and other tubes running every which way to more computers, monitors, and wires than I’ve ever seen in my life. Her eyes are dull, her face pale, and she is clearly a very sick woman.

Ellen quickly surveys the situation, approaches the high-tech bed with Charley, and asks if Lois would like Charley to lie on the bed with her. The woman nods, a small smile taking shape as she looks at Charley. She watches as Ellen carefully spreads a fresh sheet over the bed where Charley will lie. Her soft “Oh!”s of amazement and delight as Ellen helps Charley onto the bed are a gift to Charley, Ellen, and the smiling staff clustered around the door, peeking in from the hall.

It’s nothing short of a love fest. As Charley lies next to Lois, she gently strokes his head and begins to tell Ellen about a dog she had for 12 years. Ellen listens, Charley connects, and Lois talks, her voice gaining strength and energy with every word.

“He’s such a love,” she says in wonder.

From floor to floor, room to room, patient to patient, the story’s the same. Charley comes in, he and the patient connect, and someone’s healing process gets a boost.

But exactly how and when did this human-dog connection happen?

Part of the answer may be rooted deep in our shared past. One theory holds that when people stopped hunting and began forming villages, early dogs—descended from wolves—started hanging around the edges. “The dogs were attracted to the trash people threw around,” says Alan Beck, D.Sc., director of the Center for the Human-Animal Bond at Purdue University. “Dogs were useful. They ate the trash, alerted residents when predators were around, helped with hunting, and provided companionship. And people found the puppies fascinating so they kept them around.”

As time passed, the connection between dog and human evolved with each growing more tightly attuned to the other’s needs. The bond between therapy dogs and the humans they visit may be the next step on that evolutionary journey, says Beck. But, in effect, the dogs are only doing what they’ve been programmed to do for centuries: help us out.

Although the theory behind the dog-human bond is plausible, there’s a real, measurable explanation for the healing that occurs, says Rebecca Johnson, Ph.D., director of the Research Center for Human-Animal Interaction at the University of Missouri, Delta Society board member, and president of the International Association of Human Animal Interaction Organizations. She points to studies defining the neurochemical changes in our brains triggered by the dog-human connection. “The vagus nerve that runs from brain to gut is stimulated when you see, hear, touch, and smell the dog,” she explains. “That triggers the relaxation response.”

The result: the amount of the stress hormone cortisol drops and oxytocin and prolactin—two feel-good hormones—increase. “When that happens,” says Johnson, “the body can switch over from a deterioration state”—a state of illness—“to a growth state” in which healthy new cells emerge that can promote healing.

“It’s the magic of animal-assisted activity,” she adds. “Actually, it’s not magic at all. It’s medicine. Good medicine.”