The Rocky Horror Picture Show: Still Doing the Time Warp 45 Years Later

Having performed in both the touring and London productions of Hair in the early 1970s, Richard O’Brien combined his love of science fiction, horror, and comic books with his stage background into writing the musical The Rocky Horror Show. The play rapidly grew in popularity, moving from theatre to bigger theatre in England. When the opportunity came to take the tale to the screen in 1975, little did anyone involved know that their film would still be playing around the world 45 years later. I would like, if I may, to take you on a strange journey . . . this is the story of The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

O’Brien was born in England in 1942 and moved to New Zealand with his family in the 1950s. After college, he went back to England in 1964 and began working on stage and in film. O’Brien played both an Apostle and Leper in the London production of Jesus Christ Superstar; the director who cast him was Jim Sharman. Sharman would cast him again, and O’Brien shared his idea for They Came from Denton High, a musical send-up of the things that he loved, like 1950s science-fiction movies. Sharman came on board as director and gave O’Brien the idea for a new name: The Rocky Horror Show. In June 1973, the show kicked off at London’s Theatre Upstairs; it quickly became a hit, moving to bigger venues until making it to the U.K’s equivalent of Broadway, the West End.

Lou Adler was already a big name in American music when he saw Rocky in London. Adler had produced Carole King’s Tapestry, the Monterey Pop Festival, and six hits for The Mamas and The Papas, including “California Dreamin’.” He bought the U.S. theatrical rights, taking the show to the Roxy in L.A. Soon after, Michael White, who had produced the London shows, Adler, O’Brien, and Sharman were collaborating on a film version. Adler and White produced with Sharman directing and co-writing the screen adaptation with O’Brien.

The trailer for The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Uploaded to YouTube by 20th Century Studios)

In terms of casting, several members of the London cast made the jump to screen. Tim Curry (Dr. Frank-N-Furter), O’Brien (Riff Raff), Patricia Quinn (Magenta), and “Little Nell” Campbell (Columbia) had all been in productions in England. The ostensible lead roles of Brad and Janet were trickier, as studio 20th Century Fox wanted American actors in the parts; those ended up being filled by Barry Bostwick and Susan Sarandon. Charles Gray, a two-time Bond villain, played the criminologist/narrator and Jonathan Adams was cast as Dr. Scott. Marvin Lee Aday, better known as Meat Loaf, was a veteran of Broadway’s Hair and had played Eddie in the L.A. cast; he reprised Eddie for the movie, two years before the release of his massively successful Bat Out of Hell album. Background character Betty Munroe (whose wedding Brad and Janet attend early in the film) was played by Hilary Labow, which was the screen name of Hilary Farr, known today as the designer on the long-running renovation series Love It or List It.

Much of the Gothy, classic horror mood of the film came from the location at Oakley Court. The estate had been used in several Hammer Studios films, including The Brides of Dracula and The Plague of the Zombies. In Sharman’s direction, you can occasionally note some of the same wide angles and sudden zooms prevalent in Hammer features, which were meant to echo styles prevalent in the genre. Richard Hartley produced the soundtrack and handled musical arrangements on the songs that O’Brien had written. The soundtrack lists 21 official numbers, although “Once in a While” came from a deleted scene and “Super Heroes” was only seen in the U.K. until the eventual video release.

A portion of “Sweet Transvestite” from The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

The film opened 45 years ago this week in London, with the U.S. opening a few weeks later. It was not an immediate success. Outside of L.A., it was quickly pulled from theatres. Tim Deegan, a Fox executive, suggested an alternative strategy; figuring that the film might do well on the midnight circuit, as John Waters films had, Deegan got the ball rolling in New York. The Waverly Theater became ground zero for a cult phenomenon, fostering audience participation in the form of recited remarks and props. Audience members began coming to the show in costume, and screenings started to have live casts that would act out the film as it ran on the screen. Within a couple of years, the movie had become a legit cult sensation and defined the notion of the “Midnight Movie.”

The movie has actually never closed, making it the longest-running release in the history of film. Some fans and film history buffs were concerned about the status of the film when the Walt Disney Company finished its acquisition of 20th Century Fox in 2019. However, even though Disney “vaulted” a number of Fox titles, they were conscious of Rocky’s status and fandom and decided to keep it in release so that the screenings would go on.

A portion of “Hot Patootie Bless My Soul” from The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

So, just what has made it endure? At the top, the music is insanely catchy, particularly “The Time Warp.” The notion of attending a movie as a sort of costume party is fun, and the props and interaction make it a shared experience that you can join in over and over. But a deeper undercurrent is that Rocky Horror celebrates the outsider. It’s been embraced by the LGBTQ+ community, theater kids, punks, goths, comic book fans, horror and science fiction fans who get the in-jokes, and more, all of whom find connection to the film. Its influence has reverberated through the years, turning up in sitcoms like The Drew Carey Show or a 2010 episode of Glee or in films like The Perks of Being a Wallflower or Fox’s 2016 TV remake. It has endured for four-and-a-half decades, and there’s no sign that it will go away anytime soon. One supposes that it’s comforting to know that as much as some cult phenoms come and go, there will always be a light over at the Frankenstein place.

Featured image: UA Cinema Merced. The Rocky Horror Picture Show, opening night, January of 1978. (Photo by Robin Adams, General Manager, UA Cinema, Merced California, 1978. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.; Wikimedia Commons)

Pride’s Proud History: Remembering Marsha P. Johnson

There was more rainbow at my first Gay Pride than I had anticipated. I had expected some, of course, but the bandanas, the face paint, the abundance of waving flags — the sheer volume of color was startling. Still more striking was the number of people. Thousands joined in the city to celebrate the LGBTQ+ community, some wearing “I am proud of my gay son” T-shirts, some same-sex couples unapologetically kissing or holding hands, and everyone taking a stand to support the historically marginalized community.

I was a 16-year-old then, in 2016, trotting through Indianapolis with my family and friends. Even though I chose to attend Pride, it would be another year before I realized my own bisexuality. And while I understood that Pride was part of a social movement, I was shocked to learn about the violent origins of Pride and struggled to reconcile those dark days with the joyous, colorful event I had attended.

The first Pride event was held in New York on June 28, 1970, as a way to remember the Stonewall Riots that had occurred the year before. On that day in 1969, police raided the Stonewall Inn — a gay bar that was refuge to many members of the community who had been rejected by their families — arresting and aggressively handling 13 people. As a woman was shoved into a police car, she called to the bystanders to do something — and they did. The Stonewall Riots lasted six days.

A notable figure in these protests was Marsha P. Johnson, a 23-year-old, transgender black woman who was an important activist for the LGBTQ+ community. Johnson is often credited with throwing the first brick in the Stonewall Riots, though she later told a historian she arrived after it started. Born in 1945, Johnson began wearing dresses at age five but stopped because of the criticism she faced. In adulthood, she was known for her amazing, colorful outfits that were occasionally decked out with fake fruit or Christmas lights.

Her advocacy began in the 1960s after she graduated from college and moved to New York City’s Greenwich Village, the most tolerant place for LGBTQ+ people at the time — but still not a safe one. Until 1966, serving alcohol to gay people was illegal in New York City, and even afterward, public displays of homosexual behavior — including same-sex dancing, holding hands, and kissing — as well as cross-dressing, were prohibited. Places that allowed LGBTQ+ people to openly socialize, like Stonewall, were often raided by police.

Like many other LGBTQ+ people, Johnson was unable to get much work and was homeless for most of her life, making money as a sex worker and later a drag queen. The term transgender did not exist at this time, but Johnson used she/her/hers pronouns and dubbed herself Marsha P., for “Pay It No Mind,” as a response to the numerous questions about her gender.

The gay movement took off after the Stonewall Riots, and Johnson evolved with it. She opened the first homeless shelter for LGBTQ+ people and started Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, or STAR, with the help of her friend and fellow activist Sylvia Rivera, a Latina drag queen, while also supporting the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activists Alliance. STAR was established as a home for transgender people as well as a community that advocated for equal rights. Johnson and Rivera worked for their money on the streets so they could support and house other LGBTQ+ people. STAR lasted only until 1973, but it is still considered a model for other advocacy groups.

Despite her selfless work, Marsha P. Johnson — “Saint Marsha” to her friends — was met with discrimination from both the straight and gay communities. Some gays and lesbians distanced themselves from the transgender community in hopes of gaining wider public support. During early Pride parades, Johnson and the other members of STAR were placed in the back, and Rivera was even booed off the stage when she tried to speak. Still, Johnson continued to support the LGBTQ+ community, working as an AIDS activist in the ’80s and ’90s until her death.

Johnson’s body was discovered on July 6, 1992, in the Hudson River. Her death was initially deemed a suicide, but after protests from her loved ones, the cause of death was changed to drowning from unknown causes later that year. The case was eventually reopened in 2012, largely due to the work of transgender activist Mariah Lopez. Many believe it was a murder — the case is still open.

Johnson’s death wasn’t publicized much when it happened; however, with time, she is getting her deserved recognition. In 2019, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and the public arts campaign She Built NYC announced plans to build a monument honoring Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera for their work as LGBTQ+ activists. It was scheduled to be finished in 2021, but the coronavirus pandemic may push that date back. It will be the first statue depicting transgender people in the United States.

For 50 years, Pride has been a manifestation of its original chant — “Say it loud, gay is proud” — as LGBTQ+ members and allies gather to march, chant, and show the public the LGBTQ+ community. Pride has evolved from a protest to a movement: President Clinton established June as Pride Month; President Obama declared the area around the Stonewall Inn and nearby Christopher Park a national monument; celebrities, including Madonna, have performed in Pride events; and companies like Nike have produced rainbow apparel in support of the movement.

Each year I am swept up by the dancing, the free hugs booths, and the colorful, often sparkly outfits. These parts of Pride are great in their own right, but in the midst of this excitement, it is easy to forget the struggles early LGBTQ+ people faced and remember that Pride is not just a celebration: It is an ongoing struggle for equality. Even with our progress, we are still working to create a society where Marsha P. Johnson could live without judgement.

Featured image: Illustration of Marsha P. Johnson, Joseph Ratanski and Sylvia Rivera in the 1973 NYC Gay Pride Parade by Gary LeGault (Dramamonster (Gary LeGault) via the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.)

The Unknown Architect of the Civil Rights Movement

When an individual is protesting society’s refusal to acknowledge his dignity as a human being, his very act of protest confers dignity on him.

-Bayard Rustin

In 2013, while awarding a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom to civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, President Obama told a story about the organizer on the day of the 1963 March on Washington:

Early in the morning the day of the March on Washington, the National Mall was far from full, and some in the press were beginning to wonder if the event would be a failure. The march’s chief organizer, Bayard Rustin, didn’t panic. As the story goes, he looked down at a piece of paper, looked back up, and reassured reporters that everything was right on schedule. The only thing those reporters didn’t know was that the papers he was holding were blank.

Obama praised Rustin’s “unshakeable optimism” and “nerves of steel,” crediting him for living a life spent on a march toward equality. But he also recognized that the organizer’s story has been relegated to obscurity because he was openly gay.

Just last month, California governor Gavin Newsom pardoned Bayard Rustin, overturning a 1953 conviction in which he was targeted for “lude vagrancy” and marked a sex offender.

The renewed attention to Rustin’s legacy and unfair treatment comes decades after his death, but it proves the progress that he fought for is closer than ever. As a Quaker, communist, African American, homosexual, pacifist, and leading architect of the civil rights movement, Rustin’s identity and convictions afforded him the perspective to see clearly the country’s societal ills. Unlike Martin Luther King, Jr. or Malcolm X, his contributions to sweeping social justice reform were largely forgotten. Without him, it might not have been possible.

Rustin’s path to activism wound through stints with various radical groups and people. He joined the Young Communist League in 1936, but then severed ties after the Communist Party turned its attention to World War II upon Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. Rustin refused to serve in the U.S. military during the war and spent two and a half years in federal prison.

Rustin saw around him people objecting to war and injustice in strokes either too violent and radical or too passive and liberal. He found the perfect mentors in pacifist activists A.J. Muste and Asa Philip Randolph, and he went to work for the Fellowship of Reconciliation. As leaders in the labor movement, Muste and Randolph instilled in Rustin both the importance of nonviolent protest and the power of mass action. He believed these could be used to challenge discriminatory laws and economic inequality that oppressed African Americans.

After organizing the first Freedom Rides on interstate buses in the South in the 1940s (and spending 22 days on a chain gang for his civil disobedience), Rustin traveled to India to meet Mohandas Gandhi. Unfortunately, by the time he made it there, Gandhi had been assassinated. Still, the Mahatma’s teachings on combatting injustice stuck with Rustin as he continued his efforts in the U.S.

Rustin began advising a young Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on nonviolent campaigns during the successful Montgomery bus boycott in the ’50s. He had learned about the effectiveness of strikes and boycotts from the labor movement. “Our power is in our ability to make things unworkable,” he said in a speech in 1956. “The only weapon we have is our bodies, and we need to tuck them in places so wheels don’t turn.”

In 1963, the two worked together again to organize the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. A. Philip Randolph had first conceived of a mass protest in Washington, D.C. for African Americans in 1941, but his event was canceled. With Rustin at the helm, they would attempt to bring thousands of people to the city in the largest demonstration for civil rights in the country’s history.

As the date of the march approached, South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond attacked Rustin’s history of “sexual perversion,” draft dodging, and his affiliation with the Communist Party, but King defended Rustin’s invaluable place in the movement. His experience with organizing groups of people for various causes would prove instrumental in the success of the March on Washington.

Video footage from the march shows Bob Dylan and Joan Baez singing “When the Ship Comes In” as Rustin walks behind them, dragging from a cigarette. When he took the stage, Rustin began, “Ladies and gentlemen, the first demand is that we have effective civil rights legislation; no compromise, no filibuster, and that it include public accommodations, decent housing, integrated education, FAPC, and the right to vote. What do you say?” The crowd answered with a thunderous roar. The iconic event gathered more than 200,000 people in the National Mall and permanently altered the struggle for racial justice.

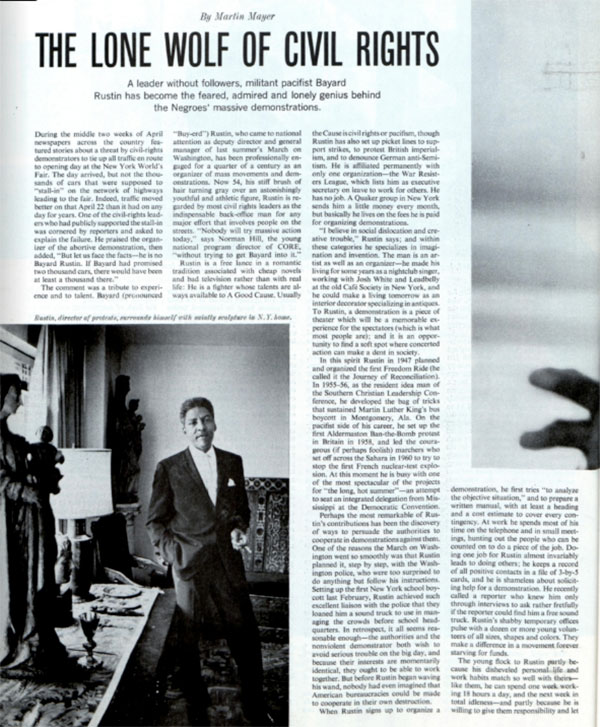

The spring after the March on Washington, this magazine published a profile of Rustin (“The Lone Wolf of Civil Rights”), calling attention to his long career in troublemaking. Rustin was decidedly nonviolent, but his approach to public protest was strictly tied to results: “Rustin insists that every demonstration he runs will be related immediately to a specific objective. Freedom rides and lunch-counter sit-ins are ideal, because they call attention directly to the evil being fought and at the same time establish a strong bargaining position for the negotiations which must be the result of any successful demonstration.”

In the Post’s report, author Martin Mayer notes Rustin’s apparent outsider status in many organizations fighting for civil rights in the ’60s. Mayer claims Rustin’s independence at the time was an organizing strategy or, perhaps, a consequence of his difficult personality, only once mentioning his “morals charge” in California. In hindsight, Rustin’s living openly as a gay man for most of his life (as anyone who met him would attest to) cost him dearly in his relationships and his ability to lead organizations. He broke off with the Fellowship of Reconciliation after several years of defending his sexual orientation to Reverend A.J. Muste, and he faced a short stint of dissociation from Dr. King for fear of sullying the leader’s reputation.

After King was assassinated, Rustin found himself at odds with the more radical Black Power movement (particularly the gun-wielding Black Panthers) as he stayed the course of marrying the civil rights movement to trade unions. Rustin became interested in moving from “protest to politics,” as far as civil rights were concerned, but he took on new issues around the world, like the plights of Soviet Jews and Thai refugees. In a 1986 speech called “From Montgomery to Stonewall,” Rustin drew comparisons between the new gay rights movement and the civil rights movement he had orchestrated:

Our job is not to get those people who dislike us to love us. Nor was our aim in the civil rights movement to get prejudiced white people to love us. Our aim was to try to create the kind of America, legislatively, morally, and psychologically, such that even though some whites continued to hate us, they could not openly manifest that hate. That’s our job today: to control the extent to which people can publicly manifest antigay sentiment.

Rustin died the year after giving that speech to a gay student group at University of Pennsylvania. In it, he assured the students that they must continue fighting for their cause no matter how difficult it was. He said that fighting for legislation was crucial, but noted that often liberation emerged from the culture influenced by the movement itself. “We never got an antilynch law,” he said, “and now we don’t need one.”

Featured image by Bert Shavitz

San Francisco, Same-Sex Marriage, and Civil Disobedience

It’s easy to think of individuals committing acts of civil obedience: The conscientious objectors that fled to Canada to avoid the draft. Student protestors staging sit-ins. Bike riders deliberately clogging traffic to protest racial injustice. But it’s harder to think of incidents where a city itself creates an act of civil disobedience. One notable example occurred 15 years ago this week when the city of San Francisco began to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. The action, though contrary to state law, would set the table for later challenges and a landmark Supreme Court decision.

In 2004, newly elected San Francisco mayor Gavin Newsom decided to direct the city-county clerk to begin issuing the licenses. Newsom’s decision came as a reaction George W. Bush’s State of the Union address, in which the president had espoused the possibility of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution to prevent same-sex marriage. With the state of Massachusetts set to allow same-sex marriage to begin in May 2004, Newsom invoked the equal protection clause of California’s state constitution as a reason for the city to begin issuing the licenses as well.

The city made the licenses available beginning February 12, and by the 13th, lawsuits were filed in opposition. On February 19, the city sued the state of California on the grounds that the statute that defined marriage in the state was unconstitutional. The next day, the California Supreme Court refused the stay on licenses that had been requested by the February 12 filings, meaning that licenses could continue to be issued. The city of San Jose waded into the fight on March 9; their city council voted 8–1 to recognize marriages of city employees performed in other jurisdictions (such as San Francisco, which is roughly 90 minutes away).

The availability of the licenses precipitated a rush of couples who wanted to get married, knowing that their window might only exist for a limited time. Reporting from that week indicates that around 900 couples were married in the first three days that licenses became available. Couples from other parts of California, and other states, descended on the area to try to get their ceremonies officiated. From February 12 to March 11, 4,000 licenses went to same-sex couples, some of whom waited in line for 12 hours. Among the more well-known couples to be wed were then-California State Assemblywoman Jackie Goldberg and Sharon Sticker; celebrity Rosie O’Donnell and her then-partner Kelli Carpenter; cartoonist Alison Bechdel and then-girlfriend Amy Rubin; filmmakers P. David Ebersole and Todd Hughes; and screenwriter David Michael Barrett and Mark Peters.

Though the issue had already drawn national attention, it had also begun to shift to the national political stage. By late February, President George W. Bush continued to publicly support an amendment to ban same-sex marriage. Some viewed this move as a pre-emptive strike to draw a line against his presumptive opponent in the next presidential election; that was Senator John Kerry, who coincidentally hailed from the other state at issue: Massachusetts. On March 11, the Supreme Court of California halted the issuance of the licenses; Mayor Newsom agreed to stop while the courts took up the issue.

Cases would travel through various levels of the court on their way to a final decision that August. On August 12, 2004, the Supreme Court of California issued a unanimous ruling that the city had violated state law by issuing the licenses. An additional decision, a 5–2 vote in the case of Lockyer v. The City and County of San Francisco, voided all of the same-sex marriages that had been performed.

The fallout continued for years. After Lockyer, the city and county of San Francisco again filed suit, leading to a 2008 Supreme Court of California decision that denying the licenses to same-sex couples was, in fact, unconstitutional. That decision, and the cases surrounding it, paved the way for multiple cases to follow. When the Obergefell v. Hodges case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, it didn’t represent a single couple; it arrived as a bundled case involving six lower court cases that had included 16 same-sex couples from four states. On June 26, 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court reached a 5–4 decision that all 50 states had to grant same-sex marriages and recognize those marriages in other states.

Today, Newsom is the governor of California. He served as mayor of San Francisco until 2011, and was the lieutenant governor of the state from 2011 until took the oath for the higher office in 2019. Despite the ultimate success of the Obergefell v. Hodges case, some challenges have arisen in court and from politicians who wish to overturn the decision. However, polls conducted by Pew Research Center and others show a consistent growth in support for same-sex marriage among the American people, with a 2018 Gallup poll demonstrating that as much of 67 percent of the population approves.

Feature Image: Same-Sex Marriage (Shutterstock)