Vonnegut Lives!

Kurt Vonnegut will never die.

Oh, he’s dead, all right; Vonnegut, the author of 14 novels and numerous short stories, passed away in 2007. But like Billy Pilgrim—the World War II soldier and protagonist of Vonnegut’s masterpiece, Slaughterhouse-Five—the writer has come “unstuck in time,” popping on and off the world stage, influencing culture from beyond the grave.

Take this summer’s book banning, for instance. The school board in Republic, Missouri, voted unanimously to remove Slaughterhouse-Five from its high school library for allegedly teaching principles contrary to the Bible. The move backfired, prompting protests and a surge in demand for the novel at the town’s public library.

“To hell with the censors!” Vonnegut once said. “Give me knowledge or give me death!”

Seeing the developing situation in Missouri, volunteers at the not-for-profit Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library in his hometown of Indianapolis offered to send every student at the high school a free copy of the writer’s science fiction novel.

No, Kurt Vonnegut isn’t going to go away so easily. This year has also seen the opening of the Vonnegut Library, paperback reissues of his books, and two new biographies in celebration of what would have been his 89th birthday on November 11.

But why do people still care about Vonnegut’s writing? What makes him still relevant? According to Charles J. Shields, author of And So It Goes: Kurt Vonnegut: A Life, one of the two biographies, it comes down to the universality of his message: “His writings, which come from the center of the most violent century in human history, simply ask, ‘Why are we here?’”

For Vonnegut, that was always a loaded question. In The Sirens of Titan he wrote, “A purpose of human life, no matter who is controlling it, is to love whoever is around to be loved.” But this love was tempered by random obstacles thrown in man’s way. Vonnegut viewed man’s struggle as the attempt to find (and give) kindness and love in an otherwise uncaring universe—a world-view shaped by his life experiences.

Born in 1922, Vonnegut was part of a prominent German-American family—until the stock market crash in 1929 forced them to scale back. After struggling for years to come to grips with the family’s reduced circumstances, Vonnegut’s mother committed suicide on Mother’s Day, 1944. The writer later confessed that his greatest fear was that he, too, would commit suicide; indeed, the chronically depressed author would attempt to kill himself 40 years after his mother’s death.

Around the time of his mother’s suicide, a fresh-out-of-college Vonnegut went to Europe to fight in World War II. Captured almost immediately during the Battle of the Bulge, he was held as a prisoner of war in Dresden, a German city known for its art, culture, and architecture. On the night of February 13, 1945, the Allies firebombed Dresden, destroying the historic city and killing between 25,000 and 35,000 people, primarily civilians. Although Vonnegut and his fellow POWs survived the bombing holed up in an underground meat locker-turned-prison nicknamed “Slaughterhouse Five,” they were devastated by the experience. The soldiers were forced to spend the next several weeks collecting the remains of the dead while the local people threw rocks at them.

“Both the Depression and the war taught Vonnegut that we are not nearly as in control of our destinies as our egos and the mythology of the ‘American Dream’ would have us believe,” says Gregory D. Sumner, author of the second recent biography, Unstuck in Time: A Journey Through Kurt Vonnegut’s Life and Novels.

After the war, Vonnegut began writing for magazines, including The Saturday Evening Post. “The No-Talent Kid” (reprinted in our Mar/Apr 2011 issue and available online) was the first of nearly a dozen short stories that he wrote for the Post. Although Vonnegut’s magazine short stories were primarily melodramas and romances, he was also drawn to science fiction. “Vonnegut was convinced he couldn’t write about the issues facing Americans during the Cold War—hydrogen bombs, conformity, materialism—in conventional ways,” Shields says. “But in science fiction, a writer can ask, ‘What if?’ and take a concept to the limit of credibility.”

In the early 1960s, Vonnegut decided to write about his experiences in World War II. But he faced a problem. “When he took shelter in the slaughterhouse, there was a city,” Shields explains. “When he came up again, the city was gone. How could he write a war novel with no middle? The solution, he discovered, was time travel.”

In Slaughterhouse-Five, the main character, Billy Pilgrim, finds himself bouncing uncontrollably through time, living his life out of sequence—including his experience as a POW during World War II and his time as an exhibit in an alien zoo on another planet. Despite the conceits of the sci-fi genre, the book grapples with the very notion of war. Released in 1969 at the height of the Vietnam War, Slaughterhouse-Five resonated profoundly with the American public, reaching number one on The New York Times best-seller list and pushing Vonnegut to the forefront of pop culture.

“Young people in particular embraced its deglorification of war and experimental style,” Sumner says. “But its universal themes transcend period or place. The book is very popular, for example, with solders and veterans of the current conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

Vonnegut used his newfound fame to transform himself into what he called a “responsible elder,” speaking at peace rallies and becoming an opponent of war in all its forms. In an age where the U.S. is still embroiled in conflicts across the globe, his message remains relevant, especially with the young; a new crop of Vonnegut fans enters college each fall.

Again, why do people—young and old—still read Vonnegut?

“Because of his honesty, wit, and faith in people, despite their flaws and the tragedies of life,” Sumner replies. “Because the seemingly ‘childish’ questions he asked, the apparently ‘simple’ style of expression he used, hold a profundity that the critics often missed.”

When released, some prominent critics did, indeed, mistake Slaughterhouse-Five’s simple prose style for plain simpleness, but history sides with Vonnegut’s legion of fans; the book is included in both Time magazine’s and Modern Library’s lists of the 100 best novels of the 20th century.

Not that Vonnegut would have been concerned about his legacy, mind you. “I don’t console myself with the idea that my descendents and my books and all that will live on,” he told a Post reporter in 1986. “I honestly believe, though, that we are wrong to think that moments go away, never to be seen again. This moment and every moment last forever.”

Kurt Vonnegut is dead.

Long live Kurt Vonnegut.

Click here to read “Miss Temptation,” one of the 11 stories that Vonnegut wrote for the Post. To view the writer’s personal artifacts on display at the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library, go here.

Treasures of the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library

The profile on former Post contributor Kurt Vonnegut in the Nov/Dec print issue of the magazine mentions the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library (KVML), which opened its doors earlier this year in Vonnegut’s hometown of Indianapolis. Despite its name, the KVML is much more than just a library. The non-profit organization also serves as an educational facility, art gallery, and community outreach center. And thanks to the support of three of Vonnegut’s children—Mark, Edie, and Nanny—the library also houses an assortment of the writer’s personal artifacts. Here are some highlights of what the KVML has on display.

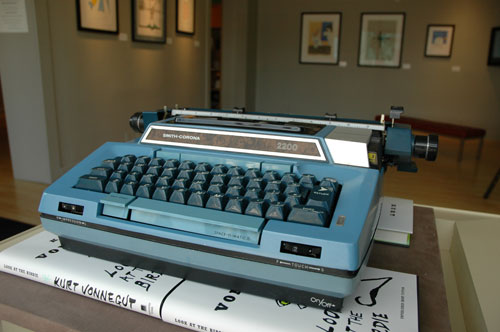

Vonnegut’s Typewriter: Vonnegut used this Smith-Corona Coronamatic 2200 during the 1970s to write books such as Breakfast of Champions and Jailbird. A bit of a technophobe, he never switched to word processors or computers, preferring the tactile nature of the typewriter instead.

Vonnegut’s Purple Heart: Vonnegut sardonically wrote in his final novel, Timequake, “I myself was awarded my country’s second-lowest decoration, a Purple Heart for frost-bite.”

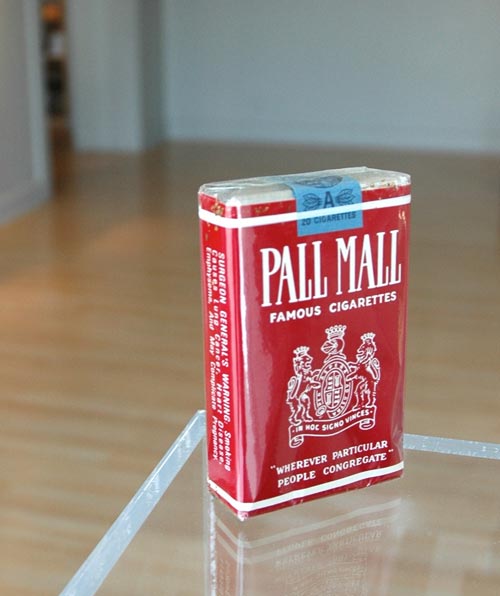

A Pack of Vonnegut’s Pall Mall Cigarettes: Throughout his life, Vonnegut was a smoker, a habit he dubbed “a classy way to commit suicide.” His children found this unopened pack of Pall Malls, his preferred brand, behind his bookcase after he died.

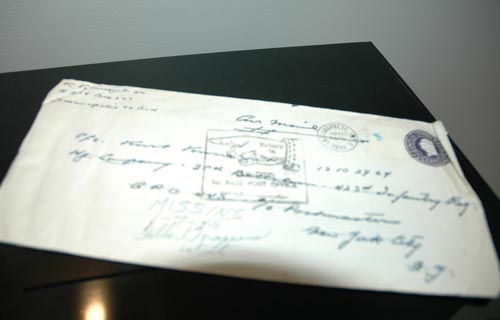

An Unopened Letter from Vonnegut’s Father: Vonnegut’s father, Kurt Sr., wrote this letter to his son during World War II, but it was lost in the mail for quite some time. When Vonnegut finally did receive it, he never opened it—and it remains sealed to this day.

Ceremonial Nazi Sword: Vonnegut wrote in Chapter 1 of Slaughterhouse-Five, “O’Hare didn’t have any souvenirs. Almost everybody else did. I had a ceremonial Luftwaffe saber, still do.”

Rooster Lamp: Vonnegut always wrote by the light of this red rooster lamp. It originated in Indiana, traveled to the east coast with with the writer, and has now returned home to “roost.”

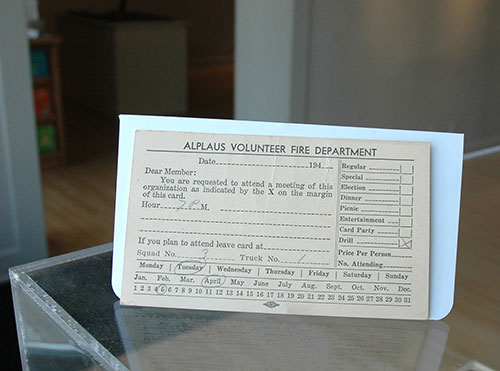

Alplaus Volunteer Firemen Reminder Card: In God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, the title character obsessively joins fire departments, spurred on by a horrific experience in World War II. Vonnegut did the same. He wrote in Slaughterhouse-Five that after the war he became “a volunteer firemen in the village of Alplaus, where [he] bought [his] first home.” This postcard from the Alplaus fire department, dated April 4, 1949, was sent as a reminder for a volunteers’ meeting.

Portrait of Kurt Sr.: This framed photograph of Vonnegut’s father hung on the wall of the writer’s work space for years and years.

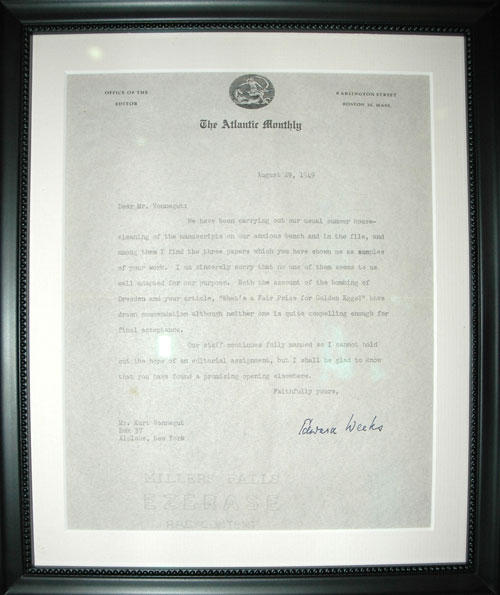

Rejection Letter: The library has quite a few of Vonnegut’s rejection letters—he liked to save them—which are periodically rotated. This one from The Atlantic Monthly is dated August 29, 1949.

To learn more about the life and work of Kurt Vonnegut, visit the KVML at 340 N. Senate Avenue in Indianapolis. The library is open noon to 5 p.m. daily except Wednesdays (closed on Wednesdays). Admission is always free.