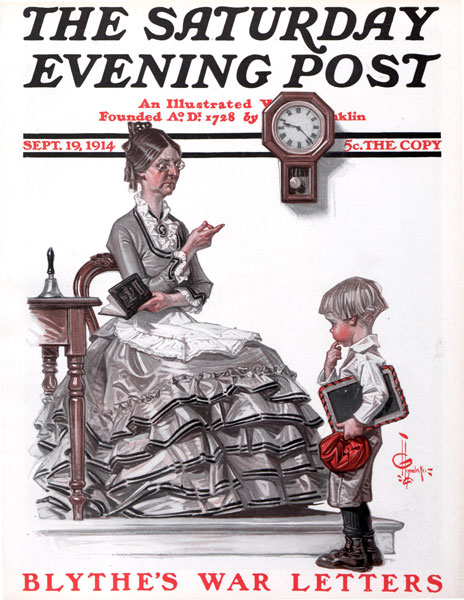

1914: London Goes To War

(Courtesy of The Library of Congress)

This series begins with a surprising eyewitness account of London by Samuel G. Blythe, published in our September 19, 1914, issue. It’s surprising because Blythe’s article contradicts the traditional account of Great Britain’s entry into the war.

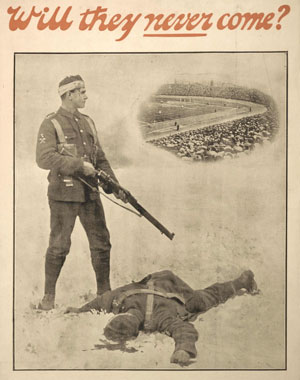

Popular histories and movies would give you the impression that the warring nations sent their soldiers off to war amid scenes of frenzied, jubilant crowds. Documentaries such as PBS’ The Great War and the upcoming exhibit at the National World War I Museum assert that there was a general expectation that the war would be over by Christmas.

Doubtless there were people who were excited and pleased by the thought of war and believed it would end quickly, decisively, and victoriously. But the Londoners Blythe saw were far from exuberant. According to his article “London in War Time,” they “watch their soldiers silently — almost stolidly. Whatever emotions they may have are held in check. … The crowds have stood silently alongside the curbs, saying nothing — not cheering — not shouting — just watching.”

(Courtesy of The Library of Congress)

Furthermore, contrary to the myth that the British expected a quick, easy victory, “the great papers are issuing daily and solemn warnings that the war is likely to be long and bloody.”

Most surprising to me is Blythe’s realization, from the war’s first week, that the coming conflict would have a vast impact. “It will change the map of Europe. It will leave its impress on the destinies of the entire civilized world for years and years to come. No person at a distance can comprehend what it all means. No person can comprehend that even here, at one of the centers of activities, or in Paris or Berlin. The impressions bulk too hugely. The mind does not grasp it all. No mind can.

“A world is being overturned. There is to be slaughter unparalleled in history. There is to be sorrow and woe and distress and ruin. There is to be mourning and weeping. There is to be the glory of arms and the grave of ambition and lust for power. Kings may lose their thrones. Republics may arise where monarchies now prevail.”

Many historians argue that the governments and people of Europe had no idea the war would overturn their world. Well, at least one reporter saw fairly clearly where it was heading, right from the start.

The Saturday Evening Post

September 19, 1914

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago:

Addressing War in Wartime: Post Editorials from the 1940s

It is relatively easy to write memorials to America’s fallen in peaceful days.

But in war time, when your family, your relatives, or your friends are risking death every day in distant lands, you can’t rely on platitudes. In these two editorials, the Post writers tried to keep the big picture in focus, while acknowledge the intense worry and suffering of family members.

The Price of Freedom is High

from September 23, 1944

Those who have lost sons or husbands in this war inevitably resent statements that the casualties are “only” a fraction of what some extravagantly pessimistic people predicted they would be. In the homes which have been darkened by the death of a soldier, or which have welcomed back the shattered remnants of vigorous youth, the burden of war’s tragedy is little lightened by assurance that it might have been worse.

Already there is a heavy toll of sacrifice. On almost any street you pick can be found a home already visited by bereavement. There will be many more before the final accounting. Nevertheless, there are grounds for hope that the awful price will not be as great as many believed. The June invasion of France cost the United States 69,526 casualties, including 11,026 killed, as against the” half million casualties” freely predicted in certain quarter at home. The soldier in England who said to a visitor, “I don’t mind going over there, but I don’t want to be counted out in advance,” is at least vindicated by the result.

There is no cause for overconfidence. Undoubtedly there will be other Tarawas and Saipans in the Pacific. But the overall results so far makes it plain that the business of landing in enemy countries, preparatory to rolling ahead in a 1944 adaptation of the 1940 blitzkrieg, was accomplished with less loss of human life than even the most hopeful prophets believed was possible. For that fact, which in no way lightens the sorrows of the victims of war’s grim lottery, we can all be grateful.

For Many There Will be No Rejoicing

from March 3, 1945

The other day we received a letter which began this way:

“For many months I have eagerly read your articles about returning veterans and your stories about the resumption of life when our loved ones return from battle. Now my eyes search for other words — words of comfort, consolation and advice about how to carry on, knowing that that beloved husband will never return. Haven’t you a special word for us thousands of wives and mothers whose men have made the supreme sacrifice? Won’t you please make an urgent plea for a prayerful reception of the armistice that is to come? Wild and hilarious rejoicing will deeply hurt us, for we have had to pay such a great price for the victory.”

It would be easy enough to write a logical and philosophical reply to that letter, pointing out that grief is, after all, the common lot of man; that millions of others all over the world must shroud their relief at victory in mourning which will follow them to the grave; and that it is for the living to wear their sorrows proudly. But such a reply wouldn’t say much to the writer of the letter quoted above or to anybody who experiences the loneliness of bereavement. Not even the knowledge that the gallant husband who gave his life would want the news of peace received with joy can allay the bitter suspicion that one is surrounded by thoughtless and callous people who pluck the fruits of other men’s sacrifices, indifferent to the price which they paid.

We cannot answer this tragic letter, nor make the dread of the hilarity of heedless people easier for the writer to endure. But it is just possible that publication of this excerpt will point up the fact that a soldier’s name on a casualty list is not just a name, but represents a hurt which will never entirely heal; that the relatives of the men who have died in this war are a special charge on the kindness and decency of all of us; that now is particularly a time when “Teach me to feel another’s woe” should be the heartfelt prayer of everyone.