Lüdvik shielded his right eye with his right hand. His elbow rested on the table.

The sun had found a spot through the window and into the corner of his vision. He was focused on a full-page advertisement that had caught his attention: “New Free Book – How to Speak and Write Masterly English in 15 Minutes a Day.” He wrote down the address on a small square of paper.

A cloud drifted in front of the sun, and he relaxed his hand back onto the table, stopping to look at his fingernails, which were immaculate. He adjusted the green reading lamp and unfolded the paper to its full span.

It was his habit, every Sunday, his one day off from tinkering with watches in his cage at Gimbels, to come to the New York City Public Library and read The New York Times. Reading the newspaper like this made him feel like a rich man who could afford not only the price of a newspaper, but the time to read the entire thing, front to back. Normally, he’d steal a few words while riding the subway, and then it was mostly upside down.

He began with the front page, left-hand article: “City Greets 1939 with Joyous Din; Vast Crowds Out.”

Lüdvik could still feel a slight throbbing in his feet from last night’s dancing. After Lüdvik’s cajoling and threatening to leave his brother behind in their dingy apartment in the Bronx, Lüdvik and Izak had found their way into a dance hall in Times Square. Lüdvik spotted the prettiest girl and asked her to dance. He laughed as he watched his brother’s shy and pained look from the sidelines. Lüdvik and the girl jitterbugged, cha-cha’d, then took in a slow dance before the crowd yelled “Happy New Year!” and she stole a kiss. Not a bad way to end and begin his first year in New York City.

Winner

Runners-Up

- “Sideshow”

by Sarah Gerard - “Party of Two”

by Mathieu Cailler - “Nothing but the Truth”

by Jim Gray - “1939 Plymouth, or The Bootlegger’s Driver”

by Lisa Trank - “The Three of Us”

by Myrna West

He pulled out the handkerchief from his pocket and unfolded it. In the center was a deep pink stain. He held the cotton square to his nose and breathed in. Cherry, roses, and licorice. In his village back home, he would have been shunned for even thinking of dancing with a non-Jewish girl.

He loved America.

The smell lingered in his nostrils as he caught sight of a headline next to the account of the New Year’s celebration. “Faulhaber Sermon Makes Concessions to the Nazis.”

Lüdvik read each word very slowly.

“Bastards,” Lüdvik spoke out loud. “Bastards.”

“Quiet, please,” a stern voice whispered in his direction.

Lüdvik folded the corner of his handkerchief and daubed his eyes, nodding apologetically.

The sun poked its way from behind another cloud. Lüdvik shook his head and placed the newspaper back on the wooden rod.

Enough bad news for one day.

The cold air hit him even before he opened the door. Pulling his overcoat tightly around his body, he tugged on his hat and tightened his scarf. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a pair of brown leather gloves. His manager at Gimbels had given them to him for a Christmas present. He’d never received a Christmas present before. The funny thing was that his boss was also a Jew, but he was learning that Jews in America were different, very different.

Feeling the soft leather against his cold skin, Lüdvik worried about how to break the news that his hours at work had been cut, since business was always slow after the holidays. Izak was not going to be happy about this.

“At least the rent is paid for January.”

Lüdvik turned the corner just as the sun hit the windshield of a car; Lüdvik stopped and again brought his hand to his eyes.

“She’s a beaut, huh?”

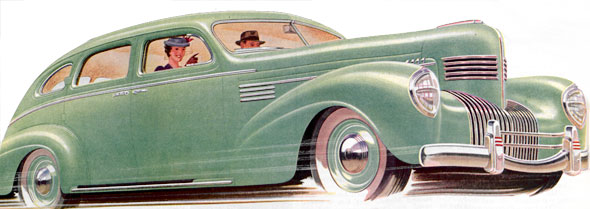

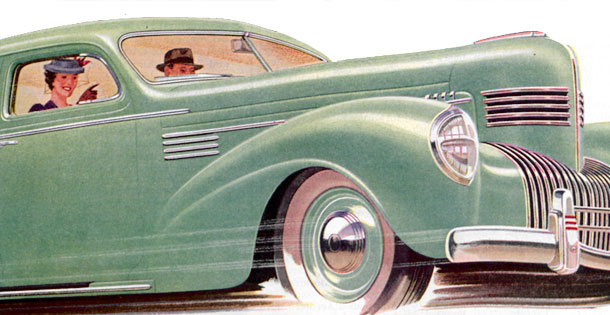

Lüdvik looked up to see a man dressed like Tyrone Power, in a wide lapelled suit with thin white stripes. His shoulders looked as if they could stretch across the block. The man was leaning against the most beautiful car Lüdvik had ever seen.

Sitting in the passenger seat was a woman with white blond hair. She wore a mink coat with the collar pulled up close around her neck. She was attractive in a way that felt familiar to Lüdvik.

“Just picked it up from the show room. Right off the assembly line.”

The car was a buttery green, with bright red leather seats that looked even softer to the touch than his gloves. The hubcaps were chrome and without a smudge. Despite the cold weather, the top was down, exposing an expansive backseat.

“Do you mind if I ask what kind of car is it?” Lüdvik asked the man.

“Do I mind? That’s funny! A 1939 Chrysler Plymouth. Less than 400 made. I’m Cartwright. My wife’s name is Greta. Greta, say hi to the young man. Say, what’s your name?”

Lüdvik liked the man’s short and straightforward answers. He bet he was the kind of man who could spend as much time as he wanted reading the newspaper.

“Lüdvik. Lüdvik Lendl.”

“Hello, Lüdvik,” Greta said softly. She smiled and he saw that she had a gap between her two top teeth.

Polish, thought Lüdvik. He’d recognize that accent anywhere. After four months of sweeping floors and cleaning bathrooms in Danzig to earn enough money for transit to Canada, the lilt and thickness of a Polish voice was forever embedded in his brain.

“Dzień dobry. Jak się masz?”

The woman’s face lit up and she jumped out of the car. She began talking rapidly with Lüdvik, mostly one-sided, as she was so excited to be speaking to someone in her mother tongue.

“Cartwright, Lüdvik’s from my mother’s part of the world. He’s Czech.”

“Well, what do ya know? Small world! Greta here escaped the Nazis by the skin of her beautiful teeth. She got out right after old Adolf took over their country.”

Lüdvik looked away uncomfortably. Greta elbowed Cartwright in the side and shook her head.

“Sorry, he forgets that some things are just too hard to speak of.”

Lüdvik tipped his hat toward Greta and extended his hand to Cartwright.

“Well, Happy New Year. I hope you’re driving somewhere nice. It was good to meet you. Do widzenia.”

His stomach growled and he wondered if the automat would even be open on New Year’s Day.

“We’re driving to California. Hollywood, California. I gotta get Greta out of the city. She hates the city, especially in the winter.”

California? Lüdvik stopped in his tracks. He turned around and spied a large picnic basket in the backseat.

“I’ve always wanted to go to California. I hear there are orange and lemon trees everywhere and all the women,” Lüdvik paused, suddenly too shy to continue.

“Are as beautiful as my Greta,” Cartwright finished for him. “Yessiree, and you can smell the ocean air as far as the mountains. It’s paradise.”

A gust of cold wind blew Lüdvik’s hat off his head. He ran a few steps to catch it and felt the cold hit his chest, through his coat, shirt, and undershirt.

“Say, don’t know if this tickles your fancy at all, but Greta can’t drive a lick and it’s a long stretch to the West Coast for one driver. We’d cover your food and board along the way, as well as some spending dough. Whad’ya think?”

Lüdvik thought of his brother Izak still asleep in their cold apartment. He wouldn’t be up for hours. He never ventured out on Sundays, as if he could catch up on lost sleep and store up some for the coming week. What would he think of this crazy scheme? Think? He’ll murder me, Lüdvik thought, and shook his head slightly.

“I have a brother in the Bronx. I can’t just leave him. He’ll have my head,” Lüdvik said.

“You can send him a telegram. What can your brother do? You’re a grown man and you’re in America now – it’s the land of opportunity! If he has any smarts, he’ll jump on the next train and join you.”

Lüdvik took in the sight of the car for a few more seconds, memorizing its lines and curves, which struck a close resemblance to the curve of Greta’s lips.

Cartwright walked to the driver’s door and opened it. Greta moved to the center of the front seat and patted the driver’s seat with her white-gloved hand.

The seat was warm from the sun. Lüdvik put his hands on the steering wheel and wrapped his fingers around it. He took a deep breath in and held it in for a few seconds, as if he knew it was the last of the city’s air he’d be breathing, at least for a while.

“What’s the fastest way out of the city?”

Cartwright jumped in next to Greta and slammed the door shut.

“Thatta boy, now you’re acting like a real American. We’ll take the George Washington Bridge to Jersey and then just keep heading west.”

Lüdvik turned the ignition key. The engine turned over smoothly. Cartwright pushed a button and the top began to unroll up toward the sky.

Lüdvik put the car in drive and gently pushed his foot down on the accelerator.

Izak stirred in his sleep. The blanket had fallen off the bed and the hissing of the radiator had turned into a steady clang. He threw the thin excuse for a blanket back up over his body and kicked the radiator three times. The clanging slowed and returned to a soft hiss.

Before he settled back to fall asleep, he lifted his head and looked at his brother’s bed. It was empty; the sheet and blanket were pulled tautly over the sagging mattress with military precision. Izak never made his bed; he figured he was just going to collapse in it at night, so why bother? But his younger brother, Lüdvik, was all about precision and timing. A walking timepiece, his brother was.

He knew Lüdvik was at the library reading his Sunday paper. Meshugener. Why would anyone be at the library when you could be warm in your bed? He chuckled to himself and quickly fell back into a deep snore, happy in the thought that his brother would bring him back a kolach and hot coffee.

The car rolled through the indiscriminate New Jersey towns, one after another. It seemed as if the entire state was asleep. No cars on the road, no people waiting for the bus or train. Lüdvik settled in behind the wheel. Occasionally, he’d glance to his right at Greta, who had fallen asleep with her head resting on Cartwright’s left shoulder.

“Wait until we get into Pennsylvania,” Cartwright said. “Past Philly and into farmland. Then you’ll get a real sense of what makes this country so great. We’ll cable your brother from there – what did you say his name is?”

“Izak, but his boss calls him Izzie.”

The mention of Izak’s name made Lüdvik tighten his grip. Now that he was a few hundred miles from the city, Lüdvik felt a sense of dread.

“Izzie, I like that. Maybe we should do the same for your name. No offense, but with the current state of things with the Krauts, you might think about changing it,” Cartwright said.

“What about Leonard?” Cartwright suggested. “That’s pretty close to Lüdvik?”

“I like Lüdvik,” Greta said in a sleepy voice. “It’s a very distinguished name.”

Leonard, Lüdvik mulled in his mind. Like Leonardo da Vinci. He liked it.

“We’ll call you Leonard for this trip and you’ll see how it fits. Or even better, Leo. If you like it, you can make it permanent,” Cartwright said. “That’s the great thing about this country. Anyone can become anything they want. A Lüdvik can become a Leo, just like that.”

He snapped his finger in the air.

“Psst, Leonard, wake up. Hey, Greta, nudge the little guy. I don’t want him to miss this sight.”

Lüdvik had taken possession of the backseat after they’d left Missouri early that morning and had finally fallen asleep somewhere between Oklahoma and Texas. It had been a raucous night with Cartwright and his friends, one that included too much beer, something called a barbeque, and an argument with Izak, whom Lüdvik finally called.

After they arrived and Cartwright and Greta were settled in with their friends and family, Lüdvik excused himself.

“Lüdvik? Lüdvik? Is dat you? Oy, your brother is ready to lose his mind with worry! Have you been kidnapped?”

“No, Mrs. Henshen,” Lüdvik responded, picturing in his mind her standing in her robe and curlers. “I’m on a business trip. Would you mind getting Izak?”

“Izak, Lüdvik’s on the line!”

“Did you get my telegram?” Lüdvik began, but didn’t get very far.

“Are you out of your mind??? Yes, I got your ferkockte telegram. What kind of meshugener nonsense is this?” Izak bellowed. “Where the hell are you? Do you have any idea how sick with worry I’ve been?”

“I’m very, very sorry, Izak,” Lüdvik said. No matter what, Izak was his older brother and the closest thing to a father figure Lüdvik had ever had.

“It’s not like I can go to the police and ask them to look for you,” Izak shouted. “What would I tell them, that my brother who has been in the country for close to 10 years, but hasn’t bothered to become a citizen, is missing? They’d find you and ship you back to stand in line at the concentration camps with the rest of the family, you idiot.”

Lüdvik could hear the panic in Izak’s voice, which had softened enough so that he could hear his older brother choking back tears as well.

“Hey, buddy,” Cartwright said, coming around the corner of the hallway. “I want to introduce you to a few people. You gonna be much longer?”

Lüdvik covered the mouthpiece with his hand.

“I’ll join you in a few minutes,” he said.

“OK, but don’t keep us waiting too long,” Cartwright said. “The party is just getting started!”

“Lüdvik,” Izak shouted into the phone. “Where the hell are you?”

Lüdvik took a big breath.

“St. Louis,” he answered. “On my way to California. Before you start shouting at me again, let me tell you about Cartwright and Greta, and the most beautiful car you’d ever wish to see.”

Lüdvik told Izak about the library, the cold morning, of meeting Cartwright and his beautiful Polish wife, Greta. He told him how much he hated New York City. He told his brother he didn’t come to America to be stuck in a cold, gray city with cold, gray people. They’d left all that behind in their homeland.

“I’ll be all right, Izak,” Lüdvik said. “Cartwright has good connections and I’ll send for you in a month or two; a first-class ticket. We don’t belong in New York, at least I don’t. Don’t worry about me. I’ll be fine.”

“What about your job, Lüdvik? You have a good job and you’re just walking away like a madman?”

Lüdvik took a deep breath. He could still feel the rattle of the pneumonia that had almost sent him back to Europe when he first landed.

“I was going to tell you last night,” he said. “They cut my hours to less than half. Something about after Christmas, it being slow. But I paid the rent for January.”

Lüdvik could hear his brother taking his time answering him.

“You must be very, very careful,” Izak said slowly knowing there was nothing he could do. “Does this Cartwright character know you’re not a ‘real’ American?”

“Don’t worry. I have to go, someone is waiting to use the phone,” Lüdvik said, avoiding his brother’s question. “I’ll call you when I get to California. Please, don’t worry.”

Lüdvik hung up the phone. He felt slightly faint and leaned against the patterned wallpaper. He stared at the family portraits that covered the hallway. Photographs of Cartwright and his family in round, wooden frames, stared back at him.

He reached into the inside pocket of his jacket and pulled out his wallet. He unfolded two photographs and sank down to the floor.

One photograph was of his family. It was frayed at the edges, but he could still make the details: his mother’s elegant and angular cheek line, his father’s round jowls and receding hairline. He and Izak stood together on one side of them, with Herschel, the next oldest, on the other. His younger siblings stood in tight semicircle in front.

Lüdvik took out a second photograph, one he and Izak had taken the day they had arrived in New York City. They were both wearing new suits and hats, but that was where the similarity stopped. Lüdvik’s suit was impeccable, with his kerchief perfectly squared in his pocket, his hat tilted just right. Izak looked ill at ease in his suit, which had become wrinkled in the summer heat.

“I promise you,” Lüdvik said and put the photos back into his pocket. “I will be all right.”

“Lüdvik, Lüdvik,” Greta said softly as she reached into the backseat and nudged his shoulder softly.

“Geesh, Greta,” Cartwright said as he pushed his foot down harder on the accelerator. “That’ll never do the trick.”

The car swerved sharply, knocking Lüdvik over and jolting him out of his deep sleep.

“That’s the ticket, Leo,” Cartwright said, laughing deeply. “Open those baby blues and take a look out!”

Lüdvik rubbed his eyes and thought he must still be dreaming.

The sky was orange and red, and stretched across the expanse as far as he could see. The colors matched the color of the ground in a seamless way. Deep, cavernous canyons went on forever. Lüdvik thought they must have driven off the earth entirely. He shook his head and pinched his thigh to see if he were still dreaming.

Cartwright pulled the car over and turned off the engine.

“Get out and stretch your legs,” Cartwright commanded. “You’ve been sleeping since Oklahoma.”

Lüdvik opened the door and stepped out.

“What is this place?” he asked.

“Why, it’s the Grand Canyon, you knucklehead! Whad’ya think, that we landed on Mars?”

With that Cartwright walked Lüdvik over to a chain link fence; the only barrier that separated the two from falling.

“But how could a place like this happen?” Lüdvik said, and shook his head. “Izak will never believe that this place exists. Never!”

“Greta, get the camera.”

Greta reached into the glove compartment and pulled out a small camera, one just like the Kodak Brownie Lüdvik had wanted, but which he decided was an extravagance.

“Come on, let’s get you looking like a real American,” Cartwright said. He pulled Lüdvik in front of the Plymouth and directed him to cross his arms across his chest. “Yeah, just like that. You know, you’re just good looking enough to be a movie actor. I know some folks who owe me a favor, if it’s a line of work you’d like to try.”

They took a series of photos and stood in front of the canyon until the sun perched just above the top rim.

“We better get going,” Cartwright said and threw the keys to Lüdvik. “Arizona is wickedly brutal, even in winter. Greta, pour the man a cup of coffee and give him some breakfast. I’m going to get some shuteye. Make sure you wake me before we get to Nevada. I have a guy I need to see.”

Greta glanced at Lüdvik in a way that made his stomach clench, and not from the lack of breakfast. He took one last look at the red horizon. Greta slid in next to him and as he turned the ignition, she formed her gloved hand into the shape of a gun against the red leather seat.

“Don’t forget, Greta,” Cartwright said and yawned. “Wake me before Nevada.”

They’d arrived in Boulder City, Nevada, just before dusk. Cartwright instructed Lüdvik to pull into a small coffee shop, where he downed a cold glass of milk and a slice of apple pie before excusing himself to the men’s room. He emerged a few minutes later, clean shaven and smiling.

“Let’s show Leo the greatest engineering feat known to mankind,” he said and left two quarters on the table.

The sound preceded their arrival. Bright white concrete glared and the thundering water seemed endless and was a stark contrast to the countless miles of desert they’d just passed through.

“C’mon, you have to stand close to really experience it,” Cartwright grabbed Lüdvik by the arm. Greta held back and shook her head back and forth with a firm, no.

“She’s afraid of heights,” he chuckled. “Boulder Dam. Took more than 20,000 men to build it. Can you imagine? More than 20,000. You know what you’re looking at, Leo.”

Lüdvik looked at the rushing water and then back at Cartwright, then shook his head.

Cartwright punched his fist onto the rail. “You’re looking at greatest country in the whole damn world.”

The marquee read in tall black letters: “The Girl of the Golden West,” with the names Jeannette McDonald and Nelson Eddy underneath. Cartwright barely waited for Lüdvik and Greta to get out of the car before he peeled away in a dust cloud.

Lüdvik and Greta settled into their seats as the newsreel starting playing. A young starlet, Judy Garland, was on the screen, waving and smiling from a flowered covered float. She was dressed in her Dorothy of Oz costume and seated next to her was a small black dog, whose wagging tail was in contrast to his growling and barking.

The newsreel announcer’s voice took on a serious tone as a subtitle flashed across the screen: “Kindertransport, Jewish Children Leave Prague for London.”

“We don’t have to stay, Lüdvik,” Greta said, taking a sharp breath in.

Lüdvik didn’t respond back. His mind turned into slow motion as he scoured the faces of the children, who were waving. Groups of well-dressed parents, stood along a silver rail. They held and kissed their children. Also wearing their best clothing, the children, in twos, boarded a waiting airplane. The story ended with a close up of the pilot with a halo of blazing light behind him.

“Maybe your brothers are on that plane,” she whispered. “Cartwright knows people in London.”

She put her hand on top of his and squeezed it gently.

“Let’s go get a drink,” she said. “I hate musicals.”

The bar was empty, save for Greta and Lüdvik, who sat at a corner table. Lüdvik cradled a whiskey on ice, while Greta sipped at some brandy.

“Sixteen years old? And why then?”

Lüdvik let the harsh flavors linger on his tongue. He looked at Greta’s round and soft face and could see small puffs of face powder that had settled in the lines above her lips.

He talked about the rabbi who had beaten his younger brother, Shmuel, and how his father had done nothing. Lüdvik explained that the rabbi would never punish the rich children, but instead would find a small infraction that one of the poorer children had done and beat them to send everyone a lesson. He’d been the subject of those beatings plenty of times and he was tough enough to take it, but when he saw the red welts on his 7-year-old brother’s back, it was a different story.

“Your father wouldn’t do anything because he was a rabbi, yes?”

Lüdvik nodded. He took a large swig and swallowed.

“So you decided to take things into your own hands instead, right?” Greta motioned to the bartender for another brandy, as well as a second drink for Lüdvik.

Lüdvik had waited in the bushes next to the rabbi’s house. Behind his hand he held a single ice skate, one that he shared with his brothers and sister to take turns with on the small pond just beyond their street. The blade was cold against his palm.

The rabbi stepped onto his front stoop. With his hands behind his back, the rabbi began to walk quickly down the street. Lüdvik knew he was rushing to get to morning prayers before the school day started.

Lüdvik gave the rabbi a head start.

When the rabbi came to a small grove of trees, Lüdvik caught up with him.

“If you ever touch anyone in my family again, I’ll finish the job,” Lüdvik said. He wiped the ice skate against the snow, leaving a thin, red stain, and threw it toward the trees.

“That was the end of that,” Lüdvik said and pushed his empty glass to the edge of the table. “He never touched anyone again.”

Greta shook her head and put her hand on Lüdvik’s, which sent a soft tingle up and down his spine.

“My father made arrangements for me to learn the watch trade. I apprenticed while he worked to get me to Canada. It was probably for the best,” Lüdvik said, sliding his hand out from underneath Greta’s. “Should we go find Cartwright?”

“He knows where to find us. This is where I always wait for him while he takes cares of his business.”

From the way Greta emphasized the word business, Lüdvik knew whatever Cartwright was up to made her uneasy. He looked at her fingernails, something he did with all women, and saw that there was a reason she wore gloves most of the time. Her nails and cuticles were bitten to the quick.

She withdrew her hands from the table.

“The liquor was one thing; in those days, everyone was dying of thirst and Cartwright had the knack, is that what you call it? The knack of being in the right place at the right time. He’d deliver the booze to the big machers, the big whigs. They paid him in cars, furs and cash. But now that the booze is flowing free again,” Greta said and took a large gulp of her brandy, “he’s moved onto other things. Things that make me nervous.”

Lüdvik remembered Greta’s hand forming the shape of a gun against the red leather upholstery.

A gunrunner. A gangster. Oy, what have I gotten himself into this time?

Cartwright appeared at the bar an hour later, reeking of whiskey and cigars. He reeled toward the table and slid into the seat next to Greta, planting a sloppy and wet kiss on her cheek.

“Ugh, you’ve been drinking,” she said and wiped the kiss off with the back of her hand. “You smell like a brothel.”

“You should have come with me, Leo,” Cartwright said. He motioned to the bartender, but Greta waved him off.

“Sorry, buddy, but we’re closing up. Besides, you look like you’ve had more than enough,” the bartender said.

“You’re a very wise man,” Cartwright shouted back. “I am fairly snonkered. Thank goodness we have our friend Leo here to drive. Where would we be without our handsome little friend from Czechoslovakia? How would my Pollack wife be kept amused from New York to California without him? Hey, I’ve got a great joke – a Pollack and a Czech walk into a bar…”

“Cartwright, please,” Greta said, her face reddening with embarrassment.

Lüdvik bought his glass down firmly on the table.

“Let’s get on the road,” he said, staring into Cartwright’s drunken gaze. “You promised me I’d see the sunset over the Pacific by tomorrow.”

Lüdvik pushed down on the accelerator. He was in no mood to linger in this town, and it wasn’t until they were in the open space of the desert that he was able to get the image of the kindertransport out of his mind.

Lüdvik looked past the windshield to endless sky and open space. Low growing grasses hugged the ground, with sand dunes rising and falling in rhythm with the movement of the car. He felt as if he were Lawrence of Arabia; a book he’d poured over countless times at the library.

“Beautiful, yes?” Greta said. They’d been silent since they’d left the bar.

“Don’t be angry at him,” Greta continued. “He only gets like that when he drinks too much. He saved my life, you know. I was a starving little nothing when we met. Just off the boat and with nothing and no one. He was working the docks and saw me. He gave me the coat off his back. Took me to the corner store and bought me a cup of coffee and a bowl of soup. I hate to think what would have become of me.”

Greta pulled her expensive coat around her tightly.

“Greta?” Cartwright’s voice came from the backseat. “Pour me a cup of coffee, would ya? I’ll give Leo here a break from driving and you can get some shut eye.”

Greta handed the Thermos cup carefully to Cartwright, who was leaning forward between her and Lüdvik. He finished one cup and then another, then tapped on Lüdvik’s shoulder, instructing him to pull over.

“I’m fine, Cartwright,” Lüdvik said. “I don’t need a break.”

“Just pull over,” Cartwright insisted. “I need to see a man about a leak.”

Lüdvik shook his head and eased over to side of the road. Cartwright stumbled out the back and walked behind a large shrub. Greta looked the other way and climbed into the backseat.

“Slide on over, partner,” Cartwright said. “I’ll take us into Los Angeles from here. This way you can take in the view. Besides, we have some talking to do.”

The San Gabriel Mountains surprised Lüdvik. They were jagged and gray, so different than the first mountains he’d seen when he arrived in Nova Scotia a decade before. Those were deep green and rolled out in gentle waves. He lost count of the sage colored yucca plants and twisted pine trees they’d passed and he wanted to stop to look at them further, but Cartwright was too busy talking to be interrupted.

“The liquor was a way out of a trail to nowhere,” Cartwright said. “I was just good looking enough to get the small bits in the movies, but the stuff bored me to tears. And there’s no money in it, unless you’re a Douglas Fairbanks. But I learned quickly that movie stars like their liquor and I knew where to get it. It was that simple. But things changed when the feds opened the gin mills again. Changed, and became more interesting.”

“Did you think about joining the army?” Lüdvik asked.

“Tried to, but the hearing in my left ear isn’t so good. Too close to a gunshot on a set,” Cartwright answered. “But I serve this country in other ways.

“You know, there’re a lot of people in your part of the world who are working ‘behind the scenes’ to stop Hitler and his cronies,” Cartwright said and looked into the rearview mirror. Greta was fast asleep. “I help supply them with what they need.”

Lüdvik jerked his head toward his companion.

“Don’t worry,” Cartwright continued. “I wouldn’t involve you. Unless you really want to learn the business. I could use a man like you. Get the feel of things and think about it. You could end up being a very wealthy man. A real American success story.”

They sped by a grove of trees and Lüdvik took in a deep breath.

“Oranges,” he said.

Cartwright swerved to the side of the rode. He jumped out and ran into the small orchard, returning with his arms full. Laughing, he poured the armful into Lüdvik’s lap.

“Welcome to California!”

“I promised you’d see the sunset in California,” Cartwright said. He and Lüdvik stood on the beach, their pant legs rolled up to their shins.

Lüdvik had no words to express what he was seeing. A huge golden orb rolled along the water’s horizon, lowering a little bit with each breath he took.

“Nothing like it in the world,” Cartwright sighed. “I could afford a bigger house and Greta is itching to have one, but I don’t want to give up this.”

“It’s like a dream,” Lüdvik said.

The two men stood and watched the sun lower, which seemed to take an eternity before it was just suddenly gone, leaving behind streaks of purple, orange, and red.

“C’mon, we’d better head back. Greta’s making a real Polish spread to welcome us home. You’ll have plenty of sunsets to catch,” Cartwright said.

“Izzy, it’s paradise,” Lüdvik whispered into the phone. “Orange groves and palm trees. Anything is possible here, I can feel it. No cold winter, no gray people or buildings. And the light, the light is like silver!”

Lüdvik waited for a response from his older brother.

“When will you be back?” Izak answered. “You’ve probably lost the few hours you did have at Gimbels. Those kinds of jobs don’t grow on trees, despite what your friend will tell you.”

Lüdvik could hear the tension in Izak’s voice.

“It’s late, Lüdvik,” Izak said with a sigh. “I have to go to bed. Don’t get sick on the oranges.”

Lüdvik hung up the phone, which was located in the little bedroom he was staying in. It was the first room he’d ever had to himself. He looked around at the simply decorated room and could feel Greta’s old world touches. He could stay in this room forever.

At first, Lüdvik did odd jobs around the house. He fixed the roof, got rid of the squeaky back door, and sealed the cracks in the driveway. At the end of each week, he’d wire half his money to his brother, putting in an extra dollar or two.

The first real job Cartwright sent him on was simple – deliver gin and cigars to a mansion in Beverly Hills. He’d never seen a place so massive and regal, not one that people actually lived in. He rang the doorbell and a dark-skinned man answered, dressed in a tuxedo. He took the delivery and instructed Lüdvik to wait.

A tall and very handsome man sauntered down the marble stairwell. A movie star. The man shook Lüdvik’s hand with vigor and smiled a broad smile. He handed him a thick envelope.

“Did my man offer you a drink?”

Lüdvik shook his head, no.

“Foster,” shouted the man. “Bring some lemonade. The Santa Anas are making everyone thirsty. So, you’re Cartwright’s new delivery guy, huh? He and I go way back.”

The movie star ushered Lüdvik through the house. He opened a back door to something Lüdvik had never seen before – a swimming pool. It was the shape of a figure eight and had graceful stone figures of unclad men on either side.

“Albert, say hello to Cartwright’s new delivery boy,” the movie star said. A tanned hand rose up and waved to Lüdvik in a way that made him slightly uncomfortable.

“You’re more than welcome to take a dip in the pool to cool off,” Albert offered.

“I have more deliveries to make,” Lüdvik answered.

“Say, I have an idea,” the movie star said. “I could use a good-looking guy like you in my next film. We start in a couple of days. Just come to the lot and tell them Ronnie told them to let you in. And if you have any friends like you, tell them to come too. Whad’ya say your name was?”

“Leo,” Lüdvik said. “Leo Lendl.”

The butler handed Lüdvik a tall glass of lemonade. He drank it quickly and put it back on the waiting silver tray.

Sundays were his days off, so early the next morning, Lüdvik showed up at the film lot. To his surprise, he was allowed inside and instructed to head to Back Lot No. 3, where a bus was waiting.

The bus lurched out of the studio and headed through the streets of Los Angeles until they got to a field. A makeshift factory town had been constructed and Lüdvik saw large movie cameras on stands. A man with a clipboard instructed Lüdvik, and the other men who had also ridden on the bus, to follow him.

Each man was handed overripe tomatoes. They were told to throw the tomatoes in the direction of the lead actor, who was the movie star Lüdvik had met the day before. He was standing on a platform and seemed to be delivering a speech of some kind. Some of the men were holding placards that had slogans on them that Lüdvik didn’t really understand, but he did what he was told to do. He and the others pounded the movie star with the tomatoes, hitting his bright white shirt and pressed pants, but not his face. They’d been given strict instructions to not let even one tomato seed hit his face. Anyone who did wouldn’t get their day’s pay.

Lüdvik was amazed at how long this process took. They’d throw the tomatoes until someone would call “cut,” at which point the movie star would be ushered away and would then return with a newly bright white shirt and pressed pants. They must have used a truckload of overripe tomatoes until another person yelled, “That’s a wrap.”

Lüdvik wasn’t even sure that the movie star knew he had been there.

The house was empty and the Plymouth was gone. A bowl of borscht was on the table with a slab of bread, which Lüdvik finished off quickly. He placed three tomatoes in a bowl and left them on the counter.

Lüdvik was going to call Izak to tell him about his crazy day when he saw a letter on his pillow.

Dear Leo,

You have to get out of here tonight. I’ve booked a ticket for a train back to New York for you; even got you a room, so you can travel in style, plus a little extra for you and your brother.

Things have turned sour for me and there’s going to be a raid. I can handle it and so can Greta, but if you get mixed up in this mess, you’ll be thrown out of the country and we both know what that will mean.

Take care of yourself.

The letter was signed by both of them, and next to Greta’s signature was the imprint of her lipstick. Lüdvik brought the letter to his nose. Jasmine.

Lüdvik exchanged the room ticket for a single seat. He leaned back into his seat and closed his eyes. He put his hand inside his coat jacket and gently tapped at the letter. Should be enough, he thought, enough for two tickets back to California.

He felt the city fade into the valley and then into the desert. It was dusk, exactly the same time he’d arrived almost two months to the day.

He craned his neck and caught the last glimpse of the setting sun, just as the train took a wide turn away from the sinking red and orange ball. ![]()

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Charming story. Reminds me of stories my grandfather would tell us of a much simpler life. To us, in 2015, these events seem unreal, yet in a much earlier time, less populated country, with limited communication, this is how things happened. I could just picture every event as you told it, and especially enjoyed the description of rooms, the car, and train.

Makes me long for the good old days.

I loved reading this, Lisa. Evocative, beautifully written, compassionate, and exciting! I, too, hope that this becomes part of your next book!

Definitely held my interest! I hope this is a book excerpt!

Two men with secrets and a beautiful woman in the middle.

Lisa, right off I enjoyed the newspaper motif. Wow. a shared ice skate? How fascinating. Poverty made fascinating.

Unpretentious and lovely writing, “buttery green… attractive in a familiar way…”

The suggested change of Ludvik’s name is a brilliantly subtle way of getting across a demeaning attitude and a threat. It felt as if something wasn’t quite right.

You prove loss is long-term gain. Experience can’t be discounted. Enjoyed the story. Thank you Saturday Evening Post for printing this story.

Wonderful story – it totally pulled me in on the first page! Great descriptive writing, I felt like I was actually there in New York and on the beach in Los Angeles. Hope to read more of your writing about your Dad’s life soon!

What a ride! Such a beautiful piece Lisa. More is right!! Bravo.

Oh my goodness!!!!! You are so talented!!!!!!!!!!!! Completely pulled in to your dad’s world…unbelievable. I want to hear the rest. Congratulations, Lisa. What a beautiful tribute to your father.

Lisa Trank, this is marvelous

I love the cinematic sweep of large and small details, the transitions, the leaps, the cuts–forward and back–and the joy of him and his meticulous daring to go West

Your sweet mythic Papa, Leonard, is so alive here. I can feel all of the parts –in this story–and the ones to come–spaning forward and back.

What a blessing this is. A gift from him given back: to him, to yourself, and the rest of us

More please!

Jack

An entrancing weaving of history, the beauty of the natural world, fascinating characters who come alive, and a riveting story that leaves me wanting moe! You are an inspiration, Lisa.

Wonderful story Lisa. I hope you think about turning it into a novel. Love the characters, and I want to know what happens next!

Beautifully told, and I am able to visualize it so well…yes, what happened next?

Another story!?

And THEN what happened? :o)

Great story!

Thank you for that wonderful story.It brought to life something of Dad that is so very precious.Beautifully written!

This is great Lisa!

Loved it!

Good job Mama, Lisa Trank, and HAPPY BIRTHDAY!

GOOD JOB!!!!!