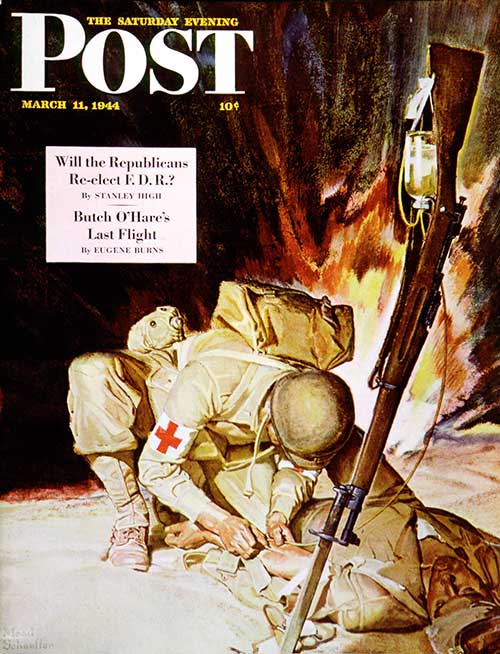

by Mead Schaeffer

March 11, 1944

My Uncle Lyle Sims came home from World War II in the spring of 1946, six months after the war was over. He had been badly wounded early in ’45 when the Allies rolled into Germany, and healing his physical wounds took a year in Walter Reed Hospital. His other wounds, the wounds to his soul, did not heal. They remained open.

Aunt Kate and I went to meet his train at Union Station in Memphis. I was 8 then, and I’d been living with her for only a few months, so what little I knew of my uncle came from photographs in her old family album. She showed me pictures of Uncle Lyle and her at their wedding, and he looked like a tough, wiry, and very happy farm boy. She also showed me shots of my parents at their wedding, and for a long time I could not look at them without crying. Both had died within two years of each other—my dad was shot down over the Pacific in 1943, and Mama had died in late ’45 of flu that turned to pneumonia. I became a sad, sickly boy living with my ailing grandmother, and if Aunt Kate hadn’t traveled all the way to Kentucky to take me to their farm near the town of Ethan, Mississippi, I would have ended up in an orphanage.

Instead I was standing there beside her in the Memphis station as we watched Uncle Lyle step down onto the platform. He was carrying his duffle bag and wearing an oversized uniform, and for a moment he stood looking lost and confused until Aunt Kate cried, “Lyle, oh, Lyle!” and ran to him, nearly knocking him down when she grabbed him. For a long time they held each other, not saying a word, while I stood back, wondering how he would react to the strange kid in his house. Finally he lifted his head from Aunt Kate’s shoulder, nodded at me and said, “So you’re Curtis Spence. I hear you’re a big help to my girl here, and I want to thank you.” He patted me on the back and turned again to Aunt Kate. “How do we get home, honey?”

“I’ve got bus tickets,” she answered. “The depot’s down the street.”

My uncle lived for only eight years after he came home, and I never really got to know him man to man. But when we walked out of the train station together, I remember feeling that I was part of an actual family again.

For several years our life together was good. As I grew older I had chores to do after school, and whenever I could I helped Uncle Lyle with the heavy work, plowing the garden, splitting firewood, cutting hay, repairing pasture fences, so that by age 13 I had become a stringy, 6-foot rail of bone and muscle. My uncle and I worked well together, but during his last years he began to have the haunted look of a man who had experienced something terrible, and I came to the realization that, bit by bit, he was turning much of the work over to me. He would observe my comings and goings from an old wooden rocker on the porch, sometimes nodding at me in approval, but whenever I saw a certain vacant expression on his face and a look of pain in his eyes, I felt that he was slipping away from us.

Winner

Runners-Up

- “Sideshow”

by Sarah Gerard - “Party of Two”

by Mathieu Cailler - “Nothing but the Truth”

by Jim Gray - “1939 Plymouth, or The Bootlegger’s Driver”

by Lisa Trank - “The Three of Us”

by Myrna West

We had entered the 1950s, and the Korean War produced a minor economic boom. Even small towns were offering work in newly built shoe and shirt factories, and you could almost take your pick of jobs in Memphis. Uncle Lyle and Aunt Kate, though, never thought of moving off the land. He had a small pension from the government, and the farm produced eggs, milk, and meat. Aunt Kate home-canned fruit and vegetables, sold eggs to the Liberty Cash grocery, and with help from neighbor Carrie Polk, who was custodian of the only telephone in our end of the county, made marvelous strawberry and blackberry jams. For my part I tinkered so much with Uncle Lyle’s old pickup that I became a fair-to-middling shade-tree mechanic, and I began doing oil changes and tune-ups on Saturdays at Sam Johnson’s service station. Sam paid me $7 for a 10-hour day, and I always had spending money.

Aunt Kate and I did all we could to make it easier for Uncle Lyle. But his health continued to fail, and by 1952, when I was 15, he began waking up in the middle of the night yelling. It took both of us to hold him in bed until he calmed down and lay back on his pillow. “The war,” Aunt Kate told me, “gave him terrible nightmares.”

She was losing hope for him. Now and then, while he slept, she would open a cabinet drawer and remove a battered notebook and a sheaf of documents. In the notebook she kept records of their income and expenses. The documents—tax receipts, the deed to the farm, burial policies, bank books, paid-up loan papers—more or less represented their net worth. There was also a life policy that Uncle Lyle had bought from Hayden Culver, the local agent for TranSouth Insurance. I watched Aunt Kate as she studied the items, adding up columns of figures in the notebook. The total never seemed to please her.

During Uncle Lyle’s last year he began taking walks alone to the pasture down behind the barn. There was a big oak stump near the stock pond where he sat watching the dusk come, and in the late afternoon coolness Aunt Kate and I usually sat together on the porch waiting for him. One evening she said to me, “Curtis, I want to show you something.” She nodded in Uncle Lyle’s direction. “Maybe it’ll help you to understand him.”

She went into the house, returning with a worn envelope. She pulled out a creased and fragile sheet of paper and handed it to me carefully.

“I wrote him a letter every day,” she said. “He answered whenever he could, but this is the letter he wrote me after he first got to the hospital. I’d like you to read it.”

The handwriting was shaky, but readable:

Honey …

I want to tell you what happened to me. The drs. say it’s okay if I want to do it, and it might help me and them. Most of it they know, but I want you to know, too.

Remember I wrote from Camp Shelby about my friends Ken and Donnie; also a fellow named Tom Fowler. We went thru basic training together and then overseas and to the front. We were on a machine gun when the Germans shelled us. It was pure hell. We got blown all to pieces. I couldn’t believe I was still alive. I was half-buried and couldn’t see. When I could see again, Tom had no head, and Donnie’s legs were gone. He died while I watched him. Ken was screaming at me but I couldn’t help him and he died, too.

Finally I dug out and started walking. I had shrapnel in my back and hip, but I don’t feel it because all I could think of was my friends dead. I walked toward the German lines, hoping they would shoot and I would be dead, too. But the Germans were gone, and troops were minesweeping the road and saw me and took me to the aid station. I’m still alive, but I can’t forget what I saw on that day no matter how much I try. It would be better if I was dead so you could collect my insurance, because I won’t be much good for you or anything else now. The doctors let me write this, but I don’t think it will help.

He signed it, “Your husband, Lyle.”

Aunt Kate watched me as I read. When I finished, I knew the letter told of something truly horrible, yet I could not imagine it. In my world people weren’t blown to pieces. The Korean War newsreels showed only columns of soldiers and distant clouds of smoke, or tanks making dust on the roads, or sometimes long lines of refugees. The soldiers who rode by in the troop trucks waved and smiled at the camera.

I handed the letter back and she slipped it carefully into its envelope. For a while we listened to the cicadas in the oak trees, and finally I said. “I wish that hadn’t happened to him.”

“So do I,” she said. “I wrote him back lots of letters. Told him I loved him and to trust the Lord, mind the doctors and get well. But I guess it didn’t help. His other letters were just notes that never said much. Just that he was doing okay.”

I tried to sound hopeful. “He’ll get better someday.”

“Maybe,” she answered. She sighed and looked intently at me. “But I’ll tell you, Curtis; I think sometimes a man can get a wound so bad it kills him, yet he keeps waking up every morning. I think it’s like that for him.”

Just then we saw Uncle Lyle closing the pasture gate, and as he walked toward us Aunt Kate said, “Maybe he’ll eat something tonight.” She pushed herself up from the rocker and went into the house.

For a long time that night, I lay thinking about the letter, and what Aunt Kate had said about Uncle Lyle living with his wound. He had been living with it for years now; but if she was right, it wouldn’t be long before that terrible dream would come for one last time, and he would not wake up again.

But it didn’t happen that way.

On a cloudy afternoon in September my uncle kissed his wife, waved to me, and walked out the back door. As usual he was wearing his old shooting coat, and Aunt Kate and I figured he was heading to the tree stump by the pond. Thanks to Mr. Slade Walker’s bull, we’d had two new calves that spring, and Uncle Lyle liked watching them at play in the pasture. A few days earlier I’d seen him actually smiling at them.

At the time I had said something like, “They’re a fine pair, ain’t they?”

Uncle Lyle had nodded. “Need to watch ’em, though, around the pond. I saw a moccasin the other day.”

“Probably just a black water snake,” I said.

“No,” he’d replied softly. “Moccasin.”

Then on that last day, 10 minutes after he’d walked out the door, I heard Aunt Kate call out from the front room, “Oh, Lord, Curtis! He took the gun.”

I found her standing before the open door of the cedar closet, a frightened look on her face. The shotgun, an old single-barrel J. C. Higgins .12-gauge, was absent from its corner. It was a dangerous worn-out relic with a hair trigger, and I had been warned from my first days with Aunt Kate never to touch it.

“He wasn’t carrying it when he left,” I said.

“Oh, but he’s slick,” she said. “He knew I’d stop him. I guarantee he slipped out sometime this morning and hid it.” She brought both hands to her cheeks. “Listen,” she said, “go find him. Just stay with him and talk to him. Tell him I said not to load that gun. He’ll listen.”

“Yes, ma’am.

But by then it was too late. I was on the porch pulling on my boots when I heard the heavy boom of the gun. Behind me I heard Aunt Kate cry out, “Oh, my God!” and I jumped from the porch and ran for the pasture. I cleared the fence in one bound while Aunt Kate was stopped at the gate, tugging at the latch.

I saw Uncle Lyle as I rounded the corner of the barn.

He was sitting on the stump, bending forward and rocking slightly back and forth. The shotgun lay on the ground at his feet, and as I approached he turned his eyes toward me and shook his head as if to warn me away. Then I saw the blood.

I said, “Hey, Uncle Lyle. What happened?”

“It was an accident,” he said. “Gun went off.”

I moved to his left side and saw where the pellets had struck him. His canvas shooting coat was bloody. He was holding it tight to his ribs with his hand, his blood seeping between his fingers. Then Aunt Kate came running up and knelt in front of him.

“Oh, Lyle,” she said. “Oh, baby, what have you done?”

He looked at her, blinking, and said, “It was an accident.”

“Well, of course it was.” She placed her hand on his cheek. “It’ll be all right. We’ll get you to a doctor.”

He whispered to her, the words barely audible. “I couldn’t bear it, Kate.”

“It’s okay, baby,” she answered quietly. “We’ll fix it.”

“I just couldn’t take it anymore.”

“Sit still now. We’ll talk about it later.” They were talking in a hushed way, as they did in bed on some nights, but I heard every word. She looked up at me and said calmly, “Get over to Carrie Polk’s. Tell her your uncle’s had an accident and we need the ambulance quick!”

“Yes’m,” I said.

I figured cutting across the pasture would be faster than going for the truck, which might not start anyway, so I ran as hard as I could. But it seemed a very long time before I reached Mrs. Polk’s, and it was even longer before the ambulance came, and by the time medics reached him, Uncle Lyle was unconscious. They carried him up the hill on a stretcher while Aunt Kate jogged beside him holding an IV bottle. On the stretcher he looked as small as a child.

She climbed into the back of the ambulance and called, “Curtis, follow us in the truck.”

The old truck started with only one backfire, and I stayed behind them all the way to the hospital in Walnut Grove. They used the siren at first, but then, just outside of town, they turned it off, and I thought, “Uncle Lyle’s dead.” And it was true. He had lost too much blood sitting there with Aunt Kate holding him, and I think she knew he was dead even before we got to the hospital. We sat together in the hall until a doctor, a bald man in a rumpled white coat, came to us and said, “He’s gone, ma’am. I’m very sorry.”

Aunt Kate stared straight ahead. Then she nodded. She didn’t cry then, nor did she cry when we drove back home late that night. She warmed a bowl of vegetable soup for me, ate nothing herself, and was still reading her Bible in the light of a kerosene lamp when I went to bed.

Later, before the sun came up, I heard her cry out from her bedroom, “Oh, Lyle!” Maybe she was awake, or maybe she dreamed and called to him in her sleep. Either way I believe she felt him, maybe even saw him, and was saying goodbye to him.

The summons to the Coroner’s Inquest came by registered mail several weeks after my uncle’s funeral, and I noticed Aunt Kate’s hand shaking as she signed for it.

In essence the letter said:

The following named individuals are required by law to appear at the Office of the Coroner, Layton County Courthouse, on November 9, 1953, to testify concerning the manner of death of Lyle David Sims. Also bring any official documents, law enforcement findings, medical reports, death certificates, etc. that are in your possession and may be pertinent to this hearing.

It was signed: “Charlene Bailey, County Coroner”

Aunt Kate’s name was there. So was mine.

The hearing was two weeks away, and for Aunt Kate it was two weeks of worry. She was sure the reason for the inquest centered on the policy Uncle Lyle had bought from TranSouth Insurance. After the funeral Mr. Culver had given her an “Application for Benefits” form and helped her to fill it out, and she was worried about the policy’s terms. They stated that the company would pay a limited benefit if death occurred within three years of the inception date, but full value after three years, and for accidental death, the double indemnity clause meant that Aunt Kate would collect $10,000. But if the death were a suicide, the beneficiary would only receive the amount that had been paid in premiums.

She said wearily, “I guess those people think he did it on purpose.”

“He said it was an accident,” I said.

She didn’t respond, and I added, “I heard him say it.”

“I know,” she said softly, “But you can’t blame them. Business is business.”

“I’ll tell ’em it wasn’t suicide.”

She sighed. “We couldn’t prove it, though, could we?”

She sounded really despondent, and for a moment I thought of saying that they, not us, would have to prove anything, but I didn’t. I remembered their whispered conversation that day in the pasture; my uncle’s tacit admission that his life had become more than he could bear, and the effort she had made to quiet and comfort him. I remembered Aunt Kate’s earlier words—that a man could be mortally wounded and still live—and I truly believed that if anything other than an accident had killed my uncle, it had to be the war, and to me that made him a hero, not a suicide.

There were several people from Ethan at the inquest: Sam Johnson had closed his station for the morning and sat on the back row in his oil-stained jumpsuit; Mrs. Polk was there, wearing her Sunday hat, and so were others, including Mr. Culver, the insurance agent, sitting beside a blue-suited man who held a briefcase. A jury box on the far side of the room contained six jurors: three sunburned men in short-sleeved shirts, one in bib overalls, and two 50ish women in starched housedresses.

We who had been summoned to testify sat on the front row of the small courtroom: Deputy Tom Blankenship, the officer who responded to Mrs. Polk’s emergency call; Dr. Luke Wendell, the County Medical Examiner, and then the Walnut Grove Hospital doctor who had seen Uncle Lyle at the Emergency Room. Aunt Kate sat beside him, and I beside her. As we watched the court reporter start to unpack her machine, the door behind the front desk opened and a small, bright-blonde woman emerged, smiled at everyone, and sat down in the swivel chair at the desk.

“My name is Charlene Bailey,” she said. “I’m the county coroner, and I thank you all for being here. I promise I’ll do my best to conduct this inquest quickly so you can all get on back home and go about your business …”

She paused, looking directly to us, the witnesses. “Now then,” she said. “Certain questions have been raised concerning the manner of death of a citizen of this county, Mr. Lyle David Sims, and it is my duty to ascertain answers to those questions. So I’m asking all of you who will be testifying to please to stand now and be sworn.”

We stood as a group, and the assistant coroner charged all of us to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Then the first witness, the hospital doctor, sat down in the witness chair and stated his name: “R.W. Caldwell, MD.”

Mrs. Bailey smiled and asked in her soft Southern voice, “Dr. Caldwell, you signed Mr. Sims death certificate, is that correct?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, reaching into his jacket pocket. “I have a copy of it right here.”

“May I see it, please?”

He passed her the document which she unfolded, studied for a minute or so, and handed back. “The certificate shows the cause of death to be a shotgun wound,” she said, “and the manner of death is accidental.”

“Yes, ma’am,” said Dr. Caldwell. “That’s based on the information I had at the time.”

Mrs. Bailey leaned forward and asked, “Have you ever attended any other person who committed suicide or attempted suicide?”

“Yes, ma’am. Several.”

“Is there anything in this case that might cause you to doubt the death was accidental?”

Dr. Caldwell frowned for a moment. “No, ma’am. Usually people who commit suicide do it with a pistol or rifle, and usually it’s a head or heart shot. Mr. Sims’ wound wasn’t necessarily fatal, and he died from shock and loss of blood. It didn’t look to be deliberate to me.”

“In your opinion, might it have been suicide?”

The doctor gave a half-shrug. “I guess it’s possible.”

Mrs. Bailey seemed to mull that over, then said, “Thank you, Doctor.” As Dr. Caldwell stepped down, the coroner said, “Dr. Wendell, if you please …”

The Medical Examiner gave testimony about the internal damage to Uncle Lyle’s body: the severe bleeding, graphic details about what the small-game pellets had done to his vital organs. Sitting next to Aunt Kate I felt her body recoil, as if the words were like whip lashes, but the doctor seemed bored by the whole process. I found myself getting angrier by the minute.

Mrs. Bailey said to him, “I assume you examined Mr. Sims’ clothing?”

“Yes, I did.”

“Tell us what you concluded from your examination.”

Dr. Wendell cleared his throat. “The shot came from very close range, penetrating the jacket he was wearing. It left gunpowder residue on the fabric, and in my opinion Mr. Sims would have died quickly if the cloth hadn’t embedded the wound and partially staunched the bleeding.”

“I see.” The coroner looked thoughtful. “So you’re saying his death was delayed because his coat slowed the loss of blood.”

“I think so, yes.”

“Then do you think Mr. Sims committed suicide?”

“He might have,” said the medical examiner. “He just didn’t do a very good job of it.”

I took a quick look at the jury, thinking the ME’s flippant attitude might have been distasteful to them, especially the women. But they seemed to accept it.

Mrs. Bailey looked out at the three people remaining on the front row. “You’re next, please, Deputy.” As Blankenship sat down, she said, “Now, sir, you were the investigating officer at the death scene?”

The deputy nodded. “Yes, ma’am. I examined the weapon and took pictures,” he said. “The gun’s a .12 gauge. Very old. It had been fired that morning, and the empty shell was still in the chamber. There was also blood on the barrel and stock.”

“Where did you find the gun?”

“In the pasture near the pond on the Sims’s place. There was a stump that had bloodstains, too, so I’m sure that’s where the shooting happened.”

“You took pictures, you say? May I see them, please?”

“Yes, ma’am.” He passed her a manila envelope containing a half-dozen black and white pictures, and she studied each for a few seconds, then picked out one and handed it back to the deputy.

“I see various things lying around the stump. Can you tell me what they are?”

The deputy looked closely at the picture. “Well, there’s the gun, some medical packaging, and a wad of blood-stained gauze. Also Mr. Sims’s shirt and coat. The coat had three unused shotgun shells in the breast pocket. I left them in the sheriff’s evidence room, and I sent the gun and the clothing to the ME’s office.”

“Very well. Anything else you want to add?”

She was talking to Blankenship, but she had turned to look at me with a frown of disapproval, because as I listened to the deputy’s testimony I almost fell from my chair. It happened in a flash, a burst of enlightenment, so that when I actually realized what I’d heard I was so jolted with excitement that my chair did a little dance.

The deputy didn’t notice. “No, ma’am,” he said. He gave a nod toward Aunt Kate and me. “I’d just like to say that Mrs. Sims and Curtis there are fine folks, and I’m sorry it happened.”

As Deputy Blankenship stepped away from the witness chair, Mrs. Bailey looked directly at me. “Now—Master Curtis,” she said. “Are you in disagreement with the deputy’s testimony?”

“No, ma’am.”

“Well, something he said seemed to light a fire under you. Do you have something to tell us?”

I swallowed hard and nodded. “Yes’m, I do.”

The witness chair was just a few steps away, but in the miniscule amount of time it took to reach it, everything came together in my mind. The Bible says, “Thou shalt not bear false witness,” and that I would never do. I had also sworn to tell, as the clerk said, “the whole truth and nothing but the truth,” and that’s what I meant to do. But until the deputy’s testimony, I hadn’t known what the truth was, but now I honestly believed it had been revealed, and I would tell the truth, the whole truth as it was made known to me in that split second, and no one could ever make me believe differently.

I took my place in the chair, and Mrs. Bailey looked at me.

“Let’s hear it.”

I took a deep breath and said, “He went to shoot a snake.”

In obvious disbelief she said, “A snake? And where was this snake?”

“It was in the pond.”

“You know this for a fact?”

“Yes, ma’am. Uncle Lyle told me about it.”

At that point I stopped talking to her. I looked out at the spectators, and the people in the jury box, and they were all watching me intently, all eager to hear what I would say, and they empowered me. I raised my voice and started talking straight to them.

“We had some new calves,” I said, “and Uncle Lyle was real fond of ’em. A day or so earlier he told me he’d seen a big moccasin in the pond, and it worried him ’cause the calves played around there. So that morning he did what any farmer would do. He got his gun and went after that snake. But the gun was in awful shape, old and rusty, and it was hard to thumb the hammer back. And if you weren’t careful with it, it could fire without you pulling the trigger.”

I paused to catch my breath. “He hadn’t been well since the war, and maybe he didn’t set the hammer right. He might’ve stumbled or dropped the gun, but somehow it fired and hit him in the side. And I know he didn’t do it on purpose. We only had four shells for that gun—in a box in the closet. The deputy said he found three shells in his coat pocket, which means Uncle Lyle took all the shells we had.” I turned to the coroner. “He wouldn’t have taken all of ’em unless he thought he might need more than one shot. And he might if he was shooting at a snake.” I looked at the people in the courtroom. “If he really meant to kill himself, he would only need to take one shell.”

For a moment everyone, including the coroner, seemed to ponder the logic of that, and then she looked toward the jury box. A stirring was growing among the spectators, and the jurors whispered to each other. Mrs. Bailey lifted a small gavel and tapped gently.

“Let’s be orderly, please.” She turned again to address the jury. “Would you folks like to hear from Mrs. Sims now?”

The jurors looked at each other, and the man in overalls, taking his cue from the others, stood up. “It ain’t necessary, ma’am.”

“I see,” said the coroner. “Are you the foreman of the jury?”

The man looked back at his fellow jurors, who were nodding. “I reckon I am, ma’am.”

“Then would you like to retire and consider the testimony?”

The foreman remained standing, turning to look, one by one, at the other jurors, each of whom in their turn whispered something to him.

He cleared his throat. “We already decided, ma’am. We find the death of Lyle David Sims to be accidental.”

As Aunt Kate and I walked down the courthouse steps, a voice called, “Mrs. Sims. Just a moment, please.”

It was the well-dressed man who had been at the inquest with Culver. He said, “I’m Hector Bennett, an attorney for TranSouth. Mr. Culver will bring your check tomorrow morning if that suits you.” He held out his hand. “Congratulations.”

For a moment Aunt Kate swayed as if she might faint, but she caught my arm, steadied herself and shook the attorney’s hand. She whispered, “Thank you, Mr. Bennett.”

“And congratulations to you, Curtis,” he said. “That snake story beats all. It won the day.” He studied me for a moment, then turned again to Aunt Kate. “Ten thousand’s a lot of money, Mrs. Sims. What will you do with it?”

“Save it,” she said, looking at me. “I want Curtis to go to college.”

“Well,” he said, “there’s a break for you, young man. Have you thought where you’d like to go?”

Never before had anybody asked about my future, and I hadn’t actually thought about it. But I found, much to my own surprise, that I had an answer.

“To law school,” I told him. “I’d like to be a defense lawyer.”

Again Bennett looked at me, giving me a strange half-smile, as if we shared a secret about something that only he and I understood.

“Doesn’t surprise me,” he said as he turned to go. “No, sir. Doesn’t surprise me at all.” ![]()

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Great story. I have been writing short stories many years, but don’t think I have ever crafted one as good as this. You are a fine writer!

Ed Nichols

As a veteran of war, this brilliant short story hits close to home. I loved it. It has heartwrenching without being heavy-handed. Service members from all conflicts return home with an overwhelming sense of uncertainty, unknowing if they’ll be able to adapt to civilian life again. Nevertheless, this piece of great short fiction shines a beaming light on the darkness that is PTSD. Thank you for writing this wonderful piece of work. That is all.

Congratulations on well-deserved praise.

I thoroughly enjoyed the story.

Thank you for showing us the invisible wounds that veterans often suffer.

Congratulations on this well deserved recognition. Enjoyed the story, especially the ending. If I ever need a good defense attorney, I’ll go lookin for Curtis.

What a wonderful short story. Once I started reading I could not stop. It was a heartwarming story. You should get it published in Readers Digest and Guideposts.

A very accomplished writer & extraordinary story, Mr. Gray!

I was immediately drawn into the characters and enjoyed reading this story.

A great story of good versus the possibility of evil.

America, in this era, produced people who would

do the right thing at any price. Stories like this keep

us thinking.

In my mind this story became a video. Excellent writing, Mr Gray. Give us more, please.

Delightfully written story. I could vividly see each

Character in my mind. Enjoyed so much ! Like to

Read more from Mr Gray !

Wow! I was moved. This story held my interest from the start. I felt the man’s anguish. It was not overdone. It was as though I was there when it all happened. That was engaging.

Very well written piece of fiction. Was growing up during that time in history, and certainly can relate to much of the story details. Would enjoy more from this talented writer. Good job!

I enjoyed this story a great deal. It immediately involves the reader and causes him to keep reading to find out what happens. Clever ending!

A beautifully written and very moving story. I enjoyed it very much.

This is a wonderful, well-written story. The writer deftly involves the reader in the lives of the characters – I was drawn into the plot and felt as if I knew them myself. It would make a great screenplay. Well done, Mr. Gray!

A very good story! So many of our men come home from war with wounds that do not heal as the character in this story. Mr. Gray brings out the fact that seeing buddies and friends die in front of you is something you never get over. I liked the way Mr. Gray brought out how times were hard after the war and families struggled to pay bills. An insurance policy was a big help and for the boy to be able to convince the jury that it was not suicide was a good twist to the story. This story definitely kept my interest and I really enjoyed reading it. Would be good to read more of Mr. Gray’s stories.

This was a very good story and I enjoyed reading it.

Beautiful story. Gives us all something to think about.