Nine years after his passing, Indianapolis native Kurt Vonnegut is still making a difference in the city that raised him. And if a fundraising effort is successful, the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library plans to do even more good in his name.

In January 2011, in a 1,100-square-foot space donated by a local law firm, the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library opened as “a nonprofit museum and cultural resource center dedicated to championing the life of Hoosier author Kurt Vonnegut and the principles of free expression, common decency, and peaceful coexistence he advocated.” From the beginning, the KVML was active in the Indianapolis community, promoting Banned Books Week, offering classes that teach teachers how to teach Vonnegut, sponsoring the annual VonnegutFest around his November 11 birthday, and hosting numerous arts and humanities events — 70 in 2015 alone. It quickly drew a nationwide audience of writers, artists, scholars, and book lovers.

“When the Vonnegut Library opened five years ago, it introduced a whole new generation to the life’s work of one of our city’s finest native sons,” Indianapolis mayor Joe Hogsett said. “The Library has been recognized as one of the things that makes Indianapolis so distinct. It is such a rare place, and indeed one of our great treasures.”

In partnership with the City of Indianapolis and other organizations, the KVML has announced that 2017 will be the Year of Vonnegut throughout Indiana’s state capital. One major milestone in this yearlong celebration will be the KVML’s move from the historic Emelie Building to its permanent and much larger home in Indianapolis’ arts district. The new location, at 646 Massachusetts Avenue, is just blocks away from both Pamela Bliss’ three-story-high Kurt Vonnegut mural and the Athenaeum Building, which was designed by Kurt’s grandfather.

[UPDATE: Because of some problems at the location, the KVML did not move to Massachusetts Avenue but to a wonderful, three-story space at 543 Indiana Avenue, not far from the Madame C.J. Walker Legacy Center.]

With the change in venue comes a change in name as well. When the new location opens on April 11, 2017, the 10th anniversary of Vonnegut’s death, the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library will be renamed the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library — still the KVML.

About a quarter of the KVML’s collection — which includes family photos, first editions and autographed editions of Vonnegut’s works, the Smith-Corona Coronamatic 2200 typewriter he wrote on during the 1970s, his Purple Heart, and even an unopened pack of his favorite cigarettes his children found behind a bookcase after he died — is confined to storage. The KVML’s current location isn’t large enough to display everything. But their new digs, with 5,400 square feet of floor space, will allow more room to display the collection. The space will also be used for a new, interactive Slaughterhouse-Five exhibit called “Time Unstuck” and a permanent exhibit centered on book banning and censorship.

The new KVML will also serve as a voter registration location.

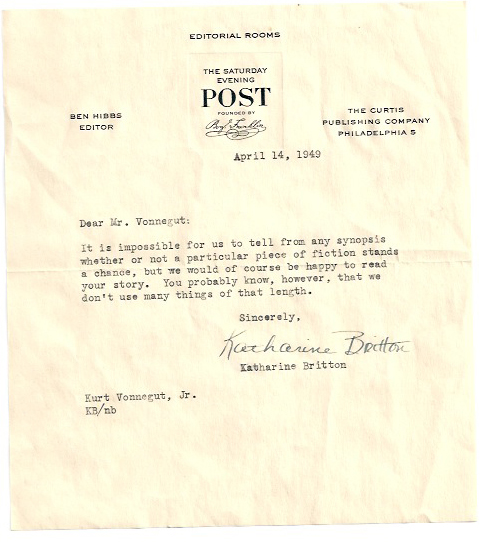

The Vonnegut Collection also includes an assortment of Vonnegut’s drawings and doodles, as well as rejection letters he received from popular magazines — a heartening sight for any aspiring author. One 1949 rejection letter for a story proposal came from The Saturday Evening Post, though it isn’t so much a rejection letter as a send-your-story-in-and-we-will-reject-it-later letter. Unfortunately, we don’t have any records of what story Vonnegut had proposed that prompted this letter.

Over the years, the Post accepted more of Vonnegut’s stories than we rejected — nine in all. The first, “The No-Talent Kid,” was published in 1952, the same year his first novel, Player Piano, hit shelves.

While readers revel in the joy Vonnegut’s stories bring, it’s hard to deny that much of what Vonnegut wrote came from a place of pain and tragedy: from his mother’s suicide in 1944, from the ongoing effects of PTSD and depression brought on by several hellish months as a German prisoner of war during World War II, and from his sister’s death from cancer in 1957 just days after her husband died in a freak train crash.

For Vonnegut, writing was, in part, a form of therapy. In 1973, he told Playboy magazine, “Writers get a nice break in one way, at least: They can treat their mental illnesses every day.” Taking this wisdom to heart, the KVML plans to host a creative writing workshop for veterans to help them express themselves and cope with what they have experienced.

It also plans to team up with Indy Eleven, Indianapolis’ North American Soccer League team, to address the fact that the state ranks No. 2 for teen suicide attempts. Through a suicide-prevention and anti-bullying writing program targeting Indiana’s middle school students, the KVML hopes to teach kids the power of the personal narrative as a more constructive and creative mechanism for coping with their problems.

But the KVML’s plans to continue Kurt Vonnegut’s legacy of humanity, compassion, and free expression are no foregone conclusion. Seeing these plans to fruition hinges on finding the funds to do it. To that end, the KVML has launched a capital campaign to raise $750,000 by July 1, 2016.

Though Vonnegut’s relationship with Indianapolis was complicated, and not always complimentary, the city was at the heart of his writing. “All my jokes are Indianapolis,” he said in 1986. “All my attitudes are Indianapolis. My adenoids are Indianapolis. If I ever severed myself from Indianapolis, I would be out of business. What people like about me is Indianapolis.”

As Indianapolis was an integral part of Vonnegut’s view of the world, the KVML “is becoming an integral part of the City of Indianapolis’ identity,” said Kip Tew, former board chairman and now head of the capital campaign. “We are endeavoring to make Indianapolis his permanent home and the place where Vonnegut fans can make their pilgrimage. This city is where the tribute to one of America’s great writers should be.”

To find out more about the KVML visit vonnegutlibrary.org.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This library sounds very intriguing to me, and a place where hours would go by without realizing it. I’m going to have to, at some point, get back there ‘on business’ and check it out as well as other cool places while visiting this major U.S. city.