“I want to smoke pot,” said Henry Featherless’s wife. Henry did not hear her. He was crouched over a kitchen counter, trying very carefully to open a can of chili without splattering himself. It was a pull-top can. with a tab that unwound a long spiral of aluminum when you lifted it. Some chili always stuck to the spiral, and when the last coil of aluminum pulled away from the rim of the can. it always splattered. It did now, all over the electric blender and the walnut box where the electric knife was kept in its slot beside the electric fork, across the top of the dishwasher, and up the front of Henry’s plaid wash ’n’ wear Father’s Day shirt.

“Henry, I want to smoke some pot.”

Henry held the unwound pull-top by its tail. “What a crazy way to open a can,” he said, feeling angry but sounding uncertain. He had always moved without calamity through the mod world. Marshall McLuhan and the Mamas and the Papas did not bother him, and he did not bother them. But the tiny defeat by the chili can unsettled him. He felt uneasy and, at 42, vaguely obsolete. “What did you say?” he asked his wife, and she told him again.

What should he have answered? What he had said was, “Oh, for God’s sake. Louise.” That was wrong; its tone said, “Act your age.” Louise was thirty-eight. She drove a station wagon, belonged to an international-relations discussion group, and played golf on Wednesday mornings.

Her answer was a tinkly and very hostile little laugh. “Why. Henry, you’re shocked,” she said.

“Of course I’m not shocked,” he said, shocked.

“Yes, you are. I bet you think pot is immoral.”

“It’s illegal, anyway. They send you to jail for something like thirty years.”

“Oh, pooh. That’s old-fashioned.”

“The cops don’t think so.”

“Silly, everyone smokes pot.”

“Who does?”

“The Richardsons, that’s who. Swingers. You just don’t know anyone who swings.”

They had met the Richardsons while visiting friends in Connecticut. She had on earrings made of Ping-pong balls. He wore hair spray, a deep tan, and a scuba-diver’s watch, and had taken Henry aside to explain that it was cheaper to lease an executive jet than fly commercial.

“Those jerks.” said Henry. His wife took a big breath. “Okay, okay,” he said quickly. “Fine. Great. Smoke pot. Swing like a chimpanzee. Who cares?”

“You mean it?” Henry’s wife clapped her hands together like a little girl.

“Why not? The world is crazy,” said Henry, still cross.

“Goody! Bring some home tomorrow night.” She kissed him and danced away. Henry looked at her. In his mind he heard the click of a lock.

The next night Henry drove home through traffic that was no worse than usual, listening as he always did to the noises made by his car’s motor and radio. They were no worse than usual, but Henry felt a terrible foreboding. That morning his wife had said in a low, breathy voice, “Don’t forget, lover.”

“What?” said Henry, although he knew.

“The pot.” said his wife, cocking her head and smiling.

Henry had laughed a rich, appreciative, good-joke laugh. watching his wife carefully. “Ah-haha-ha.” she had said. putting both arms around his waist. “Don’t fink. Henry.”

Now, steeped in finkery, he opened his front door. The hi-fi murmured Billie Holiday. There was a fire in the fireplace, and in front of it stood his wife, wearing hostess pajamas. “Hello,” she said softly. “The kids are staying over at the Prices’. Did you bring the grass?”

Henry stood there for a moment. “Uh, listen, Louise,” he began, not knowing how he would end the sentence. Then a sickening string of words skidded into his mind and out of his mouth. Keeping his face stiff and half-shutting his eyes, he said, astonishing himself, “The connection’s going to take a little time.”

Later, when the chances for a long jail sentence had begun to seem not only good but attractive, Henry wondered what else he could have said. He could have told the truth, of course, but each time he replayed the scene it came out the same way:

HENRY: Listen, Louise, this is silly as hell. I don’t know where to get any pot. The Yellow Pages haven’t got it listed. I don’t know any flower children, and except for Charlie’s fourth-grade teacher I don’t even know anyone under thirty-two. I could wear blue jeans and hang around the college, but they’d think I was a cop. Let’s drop it and get up a sky-diving group.

LOUISE: Ah-ha-ha-ha! (The tinkly laugh, showing great amusement.) Henry, you’re priceless! All you have to do is call Dirk Richardson.

HENRY: I wouldn’t call that phony charmball if I —

LOUISE: (Interrupting her husband’s search for an appropriate figure of speech.) Pooh to you. I’ll call him myself.

There the scene always faded out, leaving Henry where he had started: potless. He had stalled, not knowing what else to do, and for the first day or so it was easy. “Things are tense; there’s fuzz everywhere. The city’s up tight,” he told his wife as they drove to dinner at the Prices’ a couple of nights after the pot affair started. Louise had been impressed. “Henry’s going to get some grass, but the heat’s on,” she told Ethel Price. Ethel said, “I think it’s wonderful how you keep up with things.”

For the rest of the evening Henry accepted the situation and, he thought, underplayed nicely the role of a man who knows when the heat is on. Later, full of brandy and self-regard, he drove the baby-sitter home. Were things pretty wild at the high school, he asked — a lot of kids freaking out on pot, blowing their minds, that sort of thing?

“Hah?” At sixteen, Mary Lou was not a flower child. She was taking a preoral-hygiene course, because you could make “a hunderd-sixty, hunderd-eighty a week, and it’s steady; people always have bad enamel.” She chewed sugarless gum, and it cracked now as she worked her jaws.

But she was the only teenager Henry knew, and so he went on, “Oh, nothing. It’s just, you know, you hear there’s a lot of kids these days smoking pot.” Henry waited for a moment. “Uh, marijuana.” Mary Lou did not say anything. He went on, craftily, “I imagine it’s just talk. I wouldn’t even know how to find marijuana if I wanted it, would you, Mary Lou?”

“You’re talking funny, Mr. Featherless. I have to tell my father if anyone talks funny. Well, good night.” She got out of the car and her shoes scraped, slop-slop, as she walked across the driveway to her front door.

Henry Featherless worked for Omnicorp, a firm that, as the result of mergers, made spark plugs, women’s shoes, and foreign language textbooks. He was assistant personnel director, and although the job was not a simple one, there were stretches of his day which consisted mainly of repeating two sentences. These were, “Now, Mr. Jones, why do you want to work for Omnicorp?” and, “Suppose you tell me something about yourself.”

Ordinarily, after he had spoken one or the other of his sentences, Henry would fill in the time, as the job seeker answered, by writing letters to the editor of The New York Times in his head, or trying to remember the Vice Presidents of the United States in chronological order. Now he could think of nothing but his terrible enslavement to marijuana. “Well, now, Mr. Jones,” he had caught himself on the point of saying, “suppose you tell me where I can get some pot for my wife.”

Late one afternoon, after a day of brooding, Henry realized that the man across from him had stopped talking, and he said in an encouraging tone, “Suppose you tell me something about yourself.” The man looked at him in surprise and mumbled, “Yes, uh, well, as I said . . .” and Henry realized that they had already gone through the something-about-yourself part of the interview. As soon as he could he telephoned his wife. “Louise,” he said, “I’ll be tied up for a while. Don’t hold dinner.” With the efficiency of which a man under great stress is sometimes capable, he grabbed his coat on the run, found a bar, and ordered a drink.

Louise had been understanding on the telephone. “Is it the you-know-what?” she had whispered very loudly.

No, he had said, he just had to work late.

“It’s okay. I know you have to be careful what you say. Make Art give you the good stuff. And Henry,” she said in a voice that now sounded very small and brave, “don’t let anything happen.”

Henry had invented Art two days before, an imaginary connection, hard to find, suspicious. Art would be a good stall, he had thought at the time, until Louise gave up the nonsense about pot.

It had not worked out that way. Art’s deviousness and unreliability had made Louise angry. “Stand up to him,” she had told Henry the night before, quite sharply. “Tell your friend to make Art do what he promised.” An unnamed friend was supposed to be arranging for Art to sell pot to Henry. Louise had doubts about him, too. “I don’t trust either one of them. I don’t think they’re honest,” she had said.

Oddly enough, Louise did trust Henry. He had never had any experience with elaborate lying, and had always supposed, without thinking much about it, that a liar inevitably becomes trapped as complications are followed by inconsistencies, pursued in turn by panic, public exposure, shame, and swift expulsion from the society of man. Apparently this was not so. His own feeble lie had grown like a baby pterodactyl into a great, flapping falsehood that fed equally well on inconsistencies, good intentions, and young green shoots of cowardice. It was real; Henry himself felt queasily unreal. “I’ll have another,” he told the bartender, “and one for my problem here.” The bartender looked at him carefully, like a man deciding something, and poured one drink.

Later, or earlier, that night a small, sharp-faced man sitting next to Henry at the bar turned and said, “I suppose you have heard that the New York City sewer system has alligators in it?” Henry had not heard that, but the man had spoken quite loudly, and so Henry said yes.

“Well, it’s not true,” the small man said severely. “The animals are caymans, not alligators.” Without giving Henry a chance to comment, he went on, “Did you know that in the last six months the Kennedys have bought up every skywriting plane in the U.S.?”

“No,” said Henry.

“Of course you didn’t,” the small man said, nodding his head in a satisfied way. He slammed his hand flat on the bar, making an astonishing noise. “When you order scallops in a restaurant, what do they bring you?”

“I don’t know,” said Henry, picking up his change and edging off his stool.

“Halibut!” the man yelled, his face red. “They got a guy in the kitchen making scallops out of halibut with a cookie cutter! Want to arm-wrestle?” As Henry left, the small man was juggling ashtrays.

Henry found an all-night restaurant and ordered coffee. He noticed scallops on the menu. Halibut? Probably not, but it would be hard to tell. Why should anyone be suspicious? Halfway through his coffee Henry realized that his pot problem might be solved. He took out his address book, and under “P” he wrote, very carefully, “Halibut?” Then he drove home, playing the radio as loudly as it would go.

The next morning at breakfast he told Louise, who was not smiling, that he had missed Art again. Taking a slight risk, because he felt good, he added, “His kid was in a school play. and of course he had to be there.” His wife did not say anything. “Anyway, today’s the day. Art left word, and we should have some pot this evening.”

On his way to work Henry bought a pack of cigarettes, a folder of cigarette paper, some Worcestershire sauce, a half-ounce bottle of men’s perfume called Chainsaw, and a sun lamp. In his office he broke open four of the cigarettes, added a few pencil shavings to the tobacco, soaked the mixture with Chainsaw and Worcestershire sauce, and plugged in the sun lamp to dry the mess. He sat back, pleased. For the first time in several days he had his life firmly by the collar.

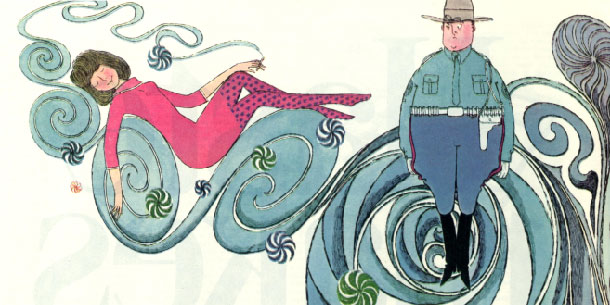

The Featherless house was raided two weeks later. “Your friend Carl drove by earlier,” Henry’s wife told him when he got home that evening.

“Carl who?”

“Carl — I forget — the state trooper. You used to go bowling with him. It’s funny, he came by in his police car a couple of times, hardly moving at all. I thought he was going to stop, but he didn’t.”

A few minutes later the door chimes rang. “Hey, here he is now,” said Henry’s wife. “Come on in, Carl.”

“Carl, sit down, have a beer,” Henry said as the policeman came into the room.

“Sorry, Mr. Featherless, this is official. I’ll have to ask you to come with me.”

The trouble was, of course, that things had gone too well. With some trouble Henry had hand-rolled his fake pot into four lumpy cigarettes. “Five bucks’ worth,” he told his wife that night as he passed them to her. “I’ll shut the curtains.”

He had watched as she lit up. He wouldn’t smoke, he had told her; someone had to stay at ground level to keep an eye on things. She nodded, looking scared. “Art said to start with a good. deep drag,” Henry said. When her coughing fit was over he asked how she felt.

“I’m not sure,” she said, looking sick. “I think I’ll smoke the rest of this later.”

Henry slept well. But the next evening things began to fall apart. “Henry,” his wife said to him shyly. “could we afford to get some more, uh, stuff, from Art?”

“You mean you smoked that junk?”

“Well, no. I have almost a whole one left. But Ethel Price is dying to come over and try some. She can pay for half.”

“Louise, listen. Wasn’t that pot awfully strong?”

“Boy, you know it,” she said, giggling. “They ought to have training wheels for beginners.”

“But it did make you feel high?”

“Well, I think it did. My eyes are still watering. Wow!” She gave Henry a hug. “Promise to see Art?”

The next day Henry got the sun lamp, the perfume, and the Worcestershire sauce out of his desk drawer again. “You did that the other day,” his secretary said, looking distrustful. Henry said something about helping his ten-year-old son with an experiment. It did not sound convincing.

As far as he could make out later, Louise and Ethel spent the entire next day aloft. They smoked four halibuts each, and during the evening, after Ethel had gone home, Louise wandered around the house giggling and saying “zonk.” Henry cooked dinner.

After his wife had gone to bed he tried some of his own pot. Was it possible that he had stumbled on a mixture that actually did have a psychedelic effect? The answer turned out to be an unpleasant no. His eyes watered and his head ached slightly, but that was all. The information did not help much. If Louise were really aviating on nothing but imagination, a full confession was the only thing that would bring her down. And she would land, of course, on Henry.

He tried to cool things the next day by saying that the heat was on again. “It’s a ghost town. Art’s visiting his mother in Buffalo.”

“That’s okay,” said Louise, untroubled. “I was going to phone Dirk Richardson anyway. He gets his from a freighter captain.” That night Henry came home with four more Worcestershire cigarettes. “Make these last,” he said, looking tired.

“I will, but I hope the heat’s off by Thursday,” said his wife. “My international-relations group is studying the drug traffic, and they all want to try pot.”

Henry did not sleep that night; his pterodactyl was now full-grown. and it swooped about his bed threatening to carry him off. “You look terrible. What’s wrong?” asked his wife the next morning, kissing him on the nose.

That night the police made their raid.

Carl Schuller pulled his cruiser up behind the station. “That do it, you think?” he said, turning to Henry.

“It should. Carl.”

“If you want I could have a couple of guys pull a search.”

“That might be pushing things, Carl. I think this ought to take care of it. You made it look like a real pinch. Thanks a lot.”

“What thanks? I pick you up on my way off duty, we go bowling. You want to get some Italian food first?”

Very late that night Henry came home. Louise was waiting, sad and small. He looked at her, holding his face stiff and his eyes half shut. “Henry! Are you all right?” she said.

He gave a little laugh. “I’ll live.”

“What did they do to you?”

“They wanted to know about pot. I told them, ‘You’re detectives, you find out.’”

“I’m sorry, Henry.”

“It’s okay, baby. Just fix me some chili.”

Some weeks later Henry’s wife looked at him thoughtfully and said, “Whatever happened to Art?”

“Art who?”

“Art, you know.”

“Oh, sure — Art,” said Henry, thinking. “Didn’t I ever tell you?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Well, you wouldn’t believe it. He got called down to the White House. He’s an adviser on urban blight. That Art,” he said, shaking his head. “A connection with connections.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Turn on, tune in, turn your eyes around. Very entertaining story that just screams “1968”! I knew right away the cover that week was the red & black burning draft card. My late parents and grandparents would NOT be happy I recently bought this cover from art.com to adorn my wall—at all, and understand completely! 🙂

Anyhow, I love how Henry was willing to practically turn himself into a pretzel, and “knew” what to do to please Louise! Insane brilliance of ‘placebo pot’ combined from the above ingredients* he bought, and she actually got high! Who would have that?!

The writing style here is clever, fun and very realistic within the context of the craziness. It would be fun to see it performed on stage as a play. I can almost picture a ’68 era Ed Asner and Jo Anne Worley as Henry and Louise. How’s that for terrific, off the cuff casting?

*Chainsaw men’s cologne? And people think Joop is a weird name!