Although Samuel Hopkins Adams was best known as a muckraking journalist who exposed patent medicine frauds, he also had a knack for fiction. The investigative journalist wrote mysteries, romantic comedies, and even a series of risqué novels under the pseudonym Warner Fabian. F. Scott Fitzgerald commended Hopkins’s fiction for authentically depicting 1920s flappers and sexuality. Adams’ fiction also provided the plots of several films in Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Published March 19, 1910

THUMP! went Thaddeus B. Drumgoole’s fat fist on his desk. So sharp was the impact that the telephone receiver leaped in the clutch, and the switchboard girl, hastily responding, learned of something to her disadvantage. As private secretary to the president of a growing trolley system I knew my cue. I sat tight and looked sympathetic.

“She says, ‘Next time it will be buckshot,’” he exploded, glaring at the note in his hand.

“It was salt last time, wasn’t it, sir?” I asked.

“And pepper,” he snapped. “Gleason got it. Serve him right, the lawyer’s cub!” He gave up one minute to a devastating frown. Then he continued in his most ponderous and presidential voice: “Curtis, do you know what it will cost to carry the road around the Massinger farm?”

“No, sir,” said I, lying as per indications.

“Twentee-five thouz-zand dol-lars,” he rasped, as if his throat was rusty. “And all on account of a dried-up, pig-headed, little wizened-faced weasel of an old maid.”

“Gleason’s description, sir? Did he get to see her, then?”

“Nobody’s seen her. When any one so much as says ‘trolley’ in the front yard she crawls into a hole and only comes out to assault the employees of my road with a shotgun, and to insult the president” — he thumped himself on the chest like a gorilla — “with jeering notes and messages. And here I stand, ready to offer her a hundred dollars for the right-of-way. She ain’t a woman at all. She’s a demon. She’s a serpent. She’s a — a — clog on the wheels of progress and of the A. B. & C. system.” Thump!

The inkwell went up in the air, fell in a faint and rolled into the presidential lap. When I’d got the Old Man mopped off and he was able to speak stenographer’s English again, he gave the C. Q. D. call for Stanley Carroll.

“Why isn’t he back?” he shouted. “Does he think a vacation is a life term? What do I pay a right-of-way man a big salary for if he’s never around when he’s needed! Where is he? When’s his time up?”

“Today, sir.”

“Then why the devil isn’t he here?”

“He is, sir. He’s been in the office since nine o’clock.”

“Then why the devil don’t you say so? What do I pay a fool secretary thirty dollars a week for if he can’t tell me what I want to know without waiting to be asked?” He lifted his fist to soak the desk again, but happened to notice the pastepot getting ready to leap for its life, and changed his mind. “Ring for Carroll!” he said.

Stanley Carroll came swinging in in his big, easy way, looking like a fresh-minted coin and wearing more kinds of clothes than a flower-bed. He always had a rainbow faded to a frazzle on pattern, anyway; but, somehow, you didn’t mind it on Stan. He wore his clothes like a butterfly.

“Hello, Curt,” Carroll said to me. “Brought you back a couple of new bass flies. Stingers! Good morning, Mr. President.”

“Wrrmph!” said Old Taddles, that being his notion of a gracious and dignified greeting to an underling. Then he tried to smile pleasantly, which was worse.

“Carroll,” said he, “I’m glad to see you back. Very glad.”

Stan took a long breath and braced himself.

“A situation has arisen, Carroll, calling for tact. Tact, I may say, is the lubricating oil of the trolley business, as executive genius — ahem! — is its electric current. You possess tact, Carroll, in a marked degree.”

“Thank you, sir,” replied Stanley. “But would you mind telling me the worst at once? I’m feeling strong today.”

“It’s the Massinger farm matter, Carroll. A vurry, vurry troublesome problem.”

“What! Hasn’t old Massinger come to time yet?”

“Mr. Massinger is dead and buried these three weeks and more. The farm has gone to his nearest surviving relative, a Miss Massinger. She may be — indeed, I do not doubt she is” — he swallowed hard — “a vurry estimmubble old lady. But difficult, Carroll, difficult!” His roving glance paused and fixed itself wistfully upon a bottle of patent insulator varnish above the desk. “We’ve simply got to have that right-of-way, Carroll,” he said. The insulator varnish was labeled “Poison.”

“In her tea,” said Stanley thoughtfully to the varnish bottle. “Personally, though, I’d mistrust a coroner’s jury. They’d be hard to get at; not like a board of aldermen.”

“I don’t know what you mean,” cried the Old Tad, jumping in his chair. “Our lawyers have done their best.” Stanley snorted. “Now, the matter rests with you. The question is, can you get the A. B. & C. through that farm or — or —”

“Or?” Stanley inquired with an accent of polite interest.

“Or not?” concluded the Old Man, limping badly at the finish. What he wanted to say war “Or shall I get somebody who can?” but he hadn’t the nerve. Stan is the one out of the whole lot of us he never dares bully, for the boy hasn’t his equal in the business as a land-grabber.

“If your lawyers haven’t muddied the water too much,” said Stanley, “I think I can. Anyway, I will, if I have to marry the old girl to do it. But it ought to be worth something special. Which brings me to a point of some importance to my unworthy self. Now, Mr. President, I’m a modest little person, if I do say it as shouldn’t. And not wishing to hang any May-day garlands on myself out of season, nevertheless and notwithstanding I may state, without impinging upon the boundaries of verisimilitude, accuracy and terseness, that when I go out after a right-of-way, that right-of-way might as well furl up its ‘No trespassing’ signs and build fences around its livestock. Failure is a word which has seldom, if ever, sullied these manly lips. It’s so, or isn’t it, Mr. President?”

“It’s so, Carroll,” agreed Thaddeus B., leaning forward and patting him on the knee, with his nose cocked in the air.

“Loving caresses are balm to a wounded soul, Mr. President,” said Stan. “But I spot this display of affection as an abortive attempt to tell from my breath whether I’ve been drinking or not. Frankness is best. I haven’t.”

“Then what the devil makes you talk like a kinematograph barker?” growled the Old Man.

“A coy but natural desire for a twenty-five percent raise of salary. Now, wait! Don’t begin while you’re feeling like that or your lips’ll get blistered.”

After swallowing a couple of times, our beloved president was able to speak without choking. Of course, it was the usual song-and-dance about the necessity of consulting the directors (dummies) and other well and favorably known lies. But he ended up with a lame sort of half-promise.

“Which is more than I really expected, Curt,” said Stanley, as I followed him into the anteroom. “Now, you tell me what’s already been done, if nothing?”

“Worse than that. The lawyers have been in the game. Young Gleason went down there, and the old witch made a pepper-and-salt design out of a perfectly good pair of white flannels with a shotgun. Then Musgrove himself undertook the cause. She parleyed with him through the door. That’s as far as he got. Before he could open up she had sprung a catechism of her own private manufacture on him. She asked him if he smoked and he said he did, and she asked him if he drank, and he said he did, and she told him to go to — — , or maybe only advised him not to — he wasn’t very clear on that point. Anyway, he remarked that he hadn’t come to discuss the future life, but a business proposition. Then she said she was going upstairs to pray for him. Goodbye. Finis!”

Stanley whistled. “That’s what Our Taddles means by ‘a vurry estim-mubble old lady,’ is it? Doesn’t sound in character to me. Well, I’ll go home and get into my frock coat and silk hat.”

“With the thermometer at 90? What for?”

“To dress the part right, Curt,” sighed the big chap. “I’ll land at the kitchen door, all figged up like a church sociable, and it’s good for a profound impression on the country old maid type of mind. They’re struck by your elegance and, at the same time, tickled to death because you don’t go hauling the front-door bell out by the roots, but act folks-y and come around back like a neighbor. Psychology, Curt, psychology!”

“Good luck,” I called after him. “And don’t forget to

Then T. B.’s bell buzzed and I had to go in and listen to him burble about what he’d do to “my right-of-way man” in case “my road” didn’t get its title clear toa pathway through the farm. It’s a curious job private secretarying to Thaddeus B. Much like hiring out as the top hinge to an escape valve.

II – BEING THE UNOFFICIAL REPORT OF STANLEY CARROL OF THE A. B. & C.

If there’s anything I don’t love it’s a cat. If there’s anything that does love me it’s a cat. Cats are always that way. Anybody who everlastingly hates ’em they lose their yearning hearts to at first sight and their one love-sick ambition is to come around and nestle against that unfortunate object of their misplaced affections. The very first thing I saw as I drove into the Massinger place was a twenty-five-pound feline, black as the ace of spades and with yellow, soulful eyes. The second object I noticed was the signpost the animal was rubbing himself against. It had been done by some amateur with a lot of time and paint to spare, that signpost. It read like this:

The border was in heavy black, and the word “Here” was bright red, with drops oozing away at the corners very suggestively. As high art it may have been a masterpiece, but as a human document I didn’t care much about it. So I stared haughtily over its head and drove up to the hitching-post. While I was hitching my mare Pussy sneaked quietly up from behind and sent a thrill of electrified ice water up my spine by rubbing against my leg. I smothered a yell the best I could and side-stepped twenty feet or so in one jump, landing about opposite the big kitchen door. The door opened conversation in a calm and precise female voice.

“Is Tom disturbing you?”

I hastily backed off a couple of yards and wondered if the sun had got to my brain. “Is the man deaf!” snapped the door. “I asked you if Tom was disturbing you.”

“Yes’m,” said I, making a leap for the newel-post. “That is, no’m. I love cats. Scat, you brute!”

“In that case,” pursued the voice of the door, “suppose you stand up like a man and state your business instead of teetering like a straddle-bug on a toadstool.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” said I, directing my remarks toward a little, dark-curtained opening about shoulder-high in the panel, “but I’m perfectly comfortable where I am. Except,” I added hopefully, “that it’s a little hot out here.”

The hint didn’t take. “You’ll find a breeze down on the highway,” suggested the voice.

Unfavorable as the situation was, I saw nothing for it but to try her with a sample of that gift of oratory which is my chief professional asset. Preparatory to turning loose an oration in my best commencement stage manner I removed my hat with a flourish, and the blamed cat reached up and clawed about two dollars’ worth of nap off of it. I made a note on my expense account and opened up.

“That which has brought me to your calm and peaceful retreat, my dear madam, is a mission of the deepest importance to all parties concerned. Upon my unworthy shoulders has fallen the mission of acting as the forerunner of a magnificent —”

“Stop right there,” interrupted the voice. “Are you a missionary or a quack doctor?”

“The noble and altruistic profession of healing,” I began, sparring for time, “is one which has ever —”

“Never mind,” said the voice. “That’s enough for a beginning. Such lovely words! Do you wish to come in?

“Do I?” I cried, almost falling off the post in my joy.

“Then wait in patience for fifteen minutes. When I am prepared to receive you I will summon you.”

It seemed more like an hour that I sat and fried on that post while my whiskered friend below begged me to come down and be petted. Just as I had begun to despair of my high collar the door said:

“Come in, young man. You will find a chair in the center of the floor. Take it. Remain quietly there.”

“Crazy as a live wire,” I said to myself as I made a quick entry, but not quick enough to shut out Furry-Purry, the cat.

There was nothing crazy about the kitchen in which I found myself. It was a great, sunny, high-ceilinged, old-fashioned room, with everything in apple-pie order. Shiny pots and pans were all over the walls. There were long brackets full of china, hanging shelves to hold all kinds of glassware, swinging doo-dabs loaded to the guards with pickles and preserves, and sprangly-armed windmills all white and fluffy with the week’s wash. In the middle of it all was the chair, set for me like a trap; a roomy old-timer, weighing fifty pounds and facing a closed door.

I sat down and remembered the Inquisition. The door swung open and showed me a dim, cool sitting room. Back in it, looking as fresh as a bunch of mint in a goblet of ice, sat the cause of all the trouble.

What’s that passage in the Bible about being not afraid with any amazement? I was so amazed that I was almost scared to death. Instead of the long, gaunt, gimlet-eyed old harridan that was all framed up in my mind, I saw the dearest, fluffiest little old fairy godmother that ever darned a sock. Her hair hung in white corkscrew ringlets all about her temples and ears. Her cheeks were round and pink. Behind her specs I could see that her eyes were big and I could guess they were brown and bright. She was a preserved peach; that’s what she was, and well-preserved at that! To and fro, swing-back, swing-forth, went the huge old rocker that could have held two of her as easily as one, for there wasn’t much more than five feet of her. I sat there and stared like a hypnotized man.

“Drat the ninny! Has he lost his tongue?”

I came out of my trance, pop! “If you are doing me the honor to address me in those soft words, ma’am, I answer ‘No,’” I said. “But I’ve lost my bearings. Have I come to the right place, or is this your enchanted castle that I’m sitting in?”

“You’ve come to Massinger’s farm, and this is my kitchen you’re sitting in. And, perhaps, you’ll have the goodness to tell me why.”

“Because you asked me. And wouldn’t it seem more home-y, more neighborly, so to speak, if you were to go a step further and ask me into the sitting room?” What I wanted was to get away from the condemned cat, who was at that moment playing pitapat with my shoelaces. Fairy Godmother would none of it.

“You’re put,” said she. “Stay put.”

“This is a lovely and entrancing kitchen, ma’am,” said I, looking all around me and arresting my glance with a bump at the point where half a dozen pairs of stockings were waggling gently in the breeze. “But,” I began, in a shocked and grieved tone, and stopped short, looking away hastily. Then I gave a frightened glance in the other direction where the white, frilly goods were rustling on the stretcher. “Oh” I said, with an embarrassed cough. “Ahem!” And I looked at the ceiling quite pointedly and blushed. It can be done by holding the breath tight in the throat, if you don’t mind a little headache afterward. The blush passed on. Fairy Godmother had one with me. The pink went clear up to her little ears. She stamped her foot. My strategy had won. “Come in!” she snapped. “And shut the door after you.” I came. The cat came, too. In a leap. He wasn’t going to lose any of my precious company — not if he knew himself. Obedient to orders I sat down over by the window. “Now,” said the Preserved Peach, “account for yourself. Do you partake of strong liquor? Are you a Methodist? Do you use hair oil? Is it your habit to bet on —”

“Hold on, ma’am,” I begged. “Spare an innocent young man that never did you any harm. I’m informed and furnished on that question game. You sewed up our legal light in a mess of queries and then shot him more full of strange seasonings than a Pure Food Law label.”

“He trampled on my begonias and swore at my cat,” she said, looking a little confused. “Anyway, I didn’t aim to hit him. I only meant to scare him.”

“You did it,” I assured her.

She caught me up, sharp as a needle. “Your legal light, you said? Then it’s as I expected. You’re one of those trolley sharks.”

Open confession was the only way now. “I am, madam, Stanley Carroll, confidential representative of the Absalomville, Bobbittstown and Cayoopany Interurban Trolley Company, Limited, very much at your service, and, with your kind attention, I beg to place before you propositions looking to our mutual benefit.”

And before she could cut in I was off in a flight of my very best style of spellbinding. I drew, for her benefit, a living and poetic word-painting of her property as it would look after the A. B. & C. had described graceful loops through the best part of it. I talked augmented real estate values in figures that no one had ever met outside an arithmetic before. I quoted from a speech that the Secretary of Agriculture never made, to prove that an electric current passing through a plum orchard not only killed all the doodle-bugs but also increased the yield of fruit from seventeen to sixty-four and five-eighths percent. I expatiated in rounded periods upon the superior advantages of having but to step over the doorsill and wave a haughty hand in order to be whirled at lightning speed to the uttermost bounds of the county, and I tactfully omitted to mention that after said haughty hand waggle the following move would be to walk half a mile to the stopping-place and wait for the next car. Finally, I promised that we wouldn’t charge her a cent for running our line through her place and that we’d even give her our handsomely-printed time-tables free. And all this time I was trying to prevent the cat from kissing my ear.

“Sign this paper, madam,” I cried, shaking the animal off for the sixth time, “and make yourself one with the mighty world which throbs and glitters on the horizon. Sign, and join hands with the pulsating forces of Absalomville. Sign, and connect yourself by bonds of steel and fire with the progress and culture of Bobbittstown and with the classic shades and metropolitan refinements of Cayoopany. Once for all, without money and without price, for the love of humanity, patriotism and our glorious nation’s commercial supremacy, sign here and — For the love of Heaven, ma’am, haven’t you got a mouse for that cat to play with?”

At that, she just tilted back her head and laughed. Such a laugh! It was all little silvery thrills and trills and quivers of pure, rollicking joyousness. A beautiful outburst of music worth going miles to hear. But — with a big, big B — there was something very far wrong with it as emerging from the face of a Preserved Peach.

As I drank it in I did some swift and suspicious thinking. I thought of the fact that Miss Massinger, of Massinger’s farm, had kept herself out of range of the human vision up to now. I thought of the delay at the doorway, and the darkened room, and the unbidden brightness of the eyes behind the glasses. And dark resentment of the wile of woman and the wrongs of man welled in my soul.

“Excuse me,” I said. “There’s a hornet in your hair.”

In two steps I was beside her, looking at the neck behind the ear. Just as I suspected; not a wrinkle to be seen. With a heart full of wrath I made a grab at the spectacles, and the wig came off, too.

Let me mention right here that the removal of the preservatives from the Preserved Peach did not in any degree affect the quality of the fruit. She might have been twenty-one, possibly twenty-two, as she turned her head slowly and with a little gasp; turned it until the brown eyes were looking directly up into mine, until the red lips, warm with laughter, were just beneath my own, and — well, I did it. That’s all; I just did it.

For a minute I thought someone had hit me from behind with a club. Then I saw the other hand coming and ducked back. The Peach got to her feet and faced me, her eyes spitting fire like a short circuit.

“Beast!” she said. “Go away! Quick! Or I’ll take the gun to you.”

“I wish you had,” said I, rubbing my ear. “You might have missed with the gun. For a bantamweight you’ve got a husky punch.”

“Will you go! And never come near this place again!”

“Thanking you for your kind invitation, I beg to decline and to inform you that I’ll be here tomorrow at the same time.”

“You dare!”

“Miss Massinger, if that really is your name

“It is. Never mind my name!”

“Fairy Godmother; found only to be lost!” I could see her mouth beginning to twinkle at the corners. “Will you grant one last favor to a martyr wounded unto death by a hand he loved not wisely but too well?”

“What do you want — idiot?” Her voice broke on the last word.

“Bid me back to learn what it all means. And then, ah, then! let me sink to rest with a soul satisfied and at peace!”

The delicious laughter came again, fullthroated, full-hearted. Knowing I had won my point I beat a hasty retreat, followed by the cat, who wailed for a vanishing hope as I drove blithely down to the main road.

That night I picnicked with the mosquitoes of Gill Center, having sent two telegrams. One was to the office:

Job will take a week. Maybe two. Satisfactory progress.

The other was to my sister:

Send full outfit white man’s clothes Gill Center. Also three pounds assorted chocolates every other day.

The next day I called at Massinger’s farm.

And the next.

The day following that, the same.

The succeeding day, ditto.

On the morrow, likewise.

The morrow’s morrow, no change.

And the seventh day was like unto the first.

Report to office: Progress.

Report to sister: Continue candy; charge to office.

Net result of assiduous devotion to interests of A. B. & C., a brand-new, wholly delightful, extremely-painful and highly-sensational experience for its loyal employee.

By the end of the week I was tying pink string around my fingers to keep me reminded that I was on the job for the line and not for myself. What I really wanted was Miss Betty Massinger, and be jiggered to her farm! As far as I got was a permit to sit in the kitchen with the cat — “That’s for penance,” said Betty — and, little by little, extract from my hostess, rocking in the peaceful inner room, the reason for her grouch against the A. B. & C. It was no real reason, after all; just that she didn’t like trolleys. She said that they spoiled landscapes, and now that Cousin Ben had left her a landscape of her own she was going to keep it unspoiled. In particular, she didn’t like the A. B. & C. They could go around her farm if they wanted to, and she wouldn’t be above riding on their line at times. But as for going through it — “Never. Never! Never!! NEVER!!! NEVER!!!!” That was her little formula.

“If they had come to me out-and-out,” she said. “But they didn’t. They snooped. I hate snoopy people.”

“I don’t snoop,” I said indignantly.

“You do. What else do you call it, coming here disguised in a silk hat and a funeral coat?”

“Well, if it comes to disguises!”

She had the grace to blush. “It was such a lark!” she pleaded. “For the lawyer people I just put on the voice. Through the door, you know. Then, when I saw you, looking so idiotic, curled up there on the post, I couldn’t resist going through the whole role. The part was copied from my aunt. She’s upstairs. Like to meet her?”

“Not particularly,” I said politely.

“There are only the two of us. Farm life is awfully dull,” she added, sighing. “I’m getting bored to death. That’s the only reason I let you come around. And I thought it was going to be so idyllic. I just leaped at the chance of getting away from the profession.”

“The profession ?”

“Yes. You didn’t think mine was an amateur performance, did you? I’m an actress. Do you object?”

“I don’t object to actresses. But I object to the way you act.”

“That’s always the way with people who come in on free passes!

“Couldn’t you go a little farther and make it a reserved seat?” I begged, looking longingly at the inner room.

“No, I couldn’t,” she returned decidedly. “You aren’t safe! That is”— she mused, and then laughed a little — “it might be arranged. As a reward for valor. Do you want to be Saint George and slay the dragon?”

“I’d rather slay the cat,” I said, shoving that enterprising animal off my knee. “But show him to me.”

“He’ll be here in a few minutes, I expect. He’s big; even bigger than you are. I don’t like him. I’ve told him not to come — seriously. He doesn’t pay any attention. Sometimes I’m — I’m afraid.”

“So’m I,” said I. “What am I to do to him?”

“Make him understand he’s to stop coming here. I hope you don’t get hurt,” she added maliciously.

“Thanks. Hope not,” I responded. “Meantime?”

“Meantime, Auntie will come down and sit with me, inside. You can keep Tom with you.”

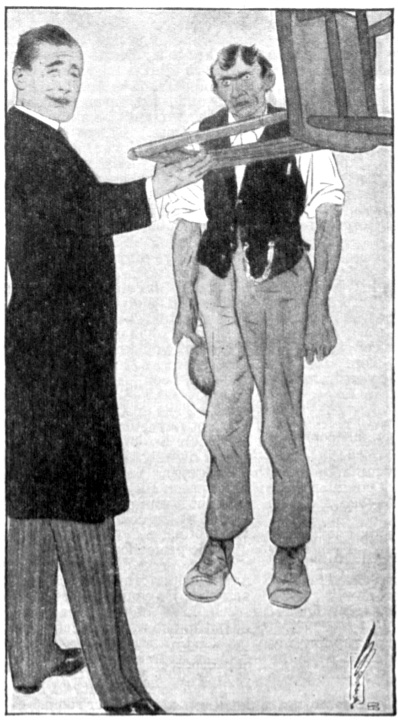

The door slammed and I was left to figure out my play. Now, I’ll do almost anything to keep out of a fight. Somebody’s sure to get hurt, and frankness compels me to admit that it’s usually the other fellow, which makes bad feeling. So, when a full-freckled, husky, six-foot-two product of the locality came hulking in with all his joints swinging loose and demanded to know what I was doing there and why, I said I was giving a physical-culture exhibition, and to prove it I picked up the fifty-pound chair and did a little juggling with it that made even the cussed cat respect me for once.

“Now,” said I, “I’m Miss Massinger’s long-lost brother Claude. I hate to scrap but I love to argue. If you’ll go away now and not come back I’ll meet you at the grocery this evening and we’ll talk crops.”

He didn’t even say good-by. But he tried to show his feelings by slamming the door after him, and that’s where, with the kind assistance of chance, he got even with me. For the cat peered out to say farewell at that moment, and the door came to on his head with a horrible scrunch. There was a stifled wail and a scrabbling of claws on the floor.

“There goes the last of my troubles,” I thought, pulling the door back as quickly as I could. “Taps for Faithful Tom.”

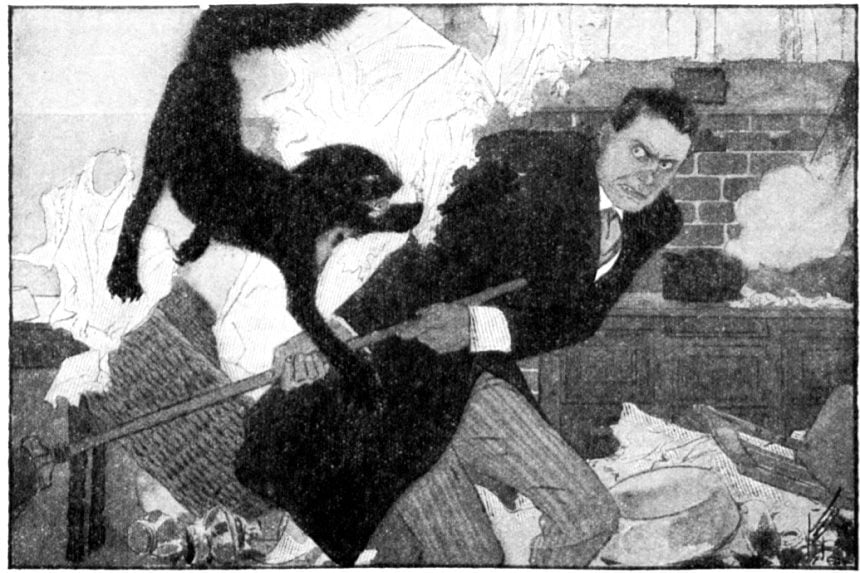

Not so. The supposed remains rolled over, did a flipflap back into the room, and the riot began. He never said a word, did that cat. He just started in to loop the loop. As a stage setting the kitchen had everything the heart could desire to bring out the fine points of the ensuing performance.

Tom’s first flight took him to the preserve shelf. About thirty-seven dollars’ worth of preserves and pickles came down and made a design on the floor that would have done finely for a canner’s coat-of-arms. The cat’s next tackle was a kerosene stove on a shelf. That left home without a minute’s hesitation and added some oil flavoring to the chowchow. Then he circulated. Glass and crockery were his specialty on the first round. The second was mostly tin and metal. It didn’t make any difference what it was; he had the magic touch. Everything he approached took a day off and joined the performance. In the midst of the uproar a shiny, swinging lamp let go all holds and fluttered down to earth, followed by one of those thumping big pans about the size of a bass drum and full of the same kind of music. While they were still rolling Pussy tried to do a circus-hoop jump around and through both of ’em, with results that outclassed a thunderstorm. As soon as he untangled himself there he sailed up after a swing full of cups and saucers. All down, the first ball. Something resembling a faint scream sounded from the inside room. As I hustled over to the door to listen a mop came out of the corner and caught me a whack over the nose that made me weep like a child. Meantime, Tom had helped himself to some lingerie off the line and was doing the Salome wiggle in the sink.

Every continuous performance has an end. It seemed up to me to furnish a curtain for this one, so I grabbed the mop, wiped the tears from my eyes and started across the room. But before I could reach him my feline friend tore his way out of the flurry and landed on the stove, with a frill over one ear. Crazy as he was, his emotional insanity had not obliterated his sense-perceptions, as the murder experts say. He knew that the stove was hot, all right. And he mentioned it in a yell that would have been human if it hadn’t been so loud. This time there was a sure-enough echo from the other room. Off he went again in the opposite direction, and, the very first lap, two soft-boiled pies floated down and spread themselves on my neck. That let out my stock of Christian patience. The next time Flying Thomas came around I made a swipe at him that would have finished the little game of one-old-cat right there if it had landed. It missed. One strike. Give you my word, the cat turned in midair like the Wright brothers and reached for me as he went by on the return trip.

Were you ever sideswiped by a cat? It’s very painful and disfiguring. I tried a counter with the handle end of the mop. Strike two, and the cat swearing at the umpire in four languages. By this time I was growing dizzy, but my eyesight was still good. Believe it or not, I saw, plain as day, my little friend pick a broomstick off the wall and sail clean across the room on it, like a witch.

Heaven’s blessing on the man who invented fly-paper! There was a sheet of it lying on the table, waiting for something to happen. Tom, the feline air-navigator, tried to soar over it, and it just simply reached out and folded him to its bosom. In a second I was on the spot with a double handful of tablecloths and towels, and in two seconds a big, white, floppy bundle was rolling around the back yard, uttering muffled and bloodcurdling yells for help.

Well, that kitchen! It looked like a pawnbroker’s sale-shop the day after the earthquake. I picked my way through the debris and put an ear to the sitting-room door. Not a sound. I opened it up a crack and looked in. In the far corner lay Auntie, her poor old toes turned up and quivering. Betty was leaning over her, rubbing her forehead with a lump of beeswax from the workbasket. I suppose she thought it was camphor.

“It’s all over,” I said in a soft, reassuring sort of voice.

Auntie took one look at me and emitted a moan from The Two Orphans. “Is he dead?” she gasped.

“I don’t think so, ma’am,” I answered.

“Just, crazy. He was still wiggling when I threw him out.”

Betty’s eyes were all big and frightened as she lifted them to me. “You’d better go,” she said stonily. “I didn’t know you were a brute.”

That fairly got on my temper. At the same time I remembered that, after all, I was working for the company.

“I’ll go,” I said, “when my papers are signed.”

“I’ll sign anything to get rid of you for good,” said Betty viciously. “Of course, it’s the company all the time. I might have known. Well, Mr. Right-of-Way Man, what’s it worth?”

Even then I wasn’t going to give her anything less than a fair price.

“Five hundred dollars,” I said, with a heart like lead. “And fifty extra to cover damage. Sign here.”

She hesitated a bit, stealing one quick glance at me and looking away again. Then she signed. “Much good may it do you!” she said.

The shivering old aunt put her name down as witness.

“It seems like blood money,” she wailed. “Our poor, martyred neighbor! Though I couldn’t abide his freckles!”

“Freckles? Neighbor? “I almost yelled. “Did you think that four-corners hayseed put up any such fight against me? It was the cat!”

After that — the deluge. Something told me that the time to depart had arrived. I made two jumps of it for my rig. As I drove out of the place with my romance dead in my heart and my neck all botched up with pumpkin pie like a Sunday-school picnic ground, I heard a noise from the ridgepole of the woodshed. There sat Indestructible Tom, the nine-lived wonder, with his whiskers done up in fly-paper and two feet of white ruffle half-masted on his tail, trying to tell me what he thought of me between spits.

III

The office force of the A. B. & C. Interurban Trolley Company, Limited, sat up as one man and took notice when Stanley Carroll’s final wire in the Massinger right-of-way affair came in. Brief and businesslike it was:

Got it. Sidetracked for minor repairs. Back in a week.

Before the time was up the story of the cat had drifted into headquarters. I suppose old Auntie had leaked it at some sewing circle. From Thaddeus B. Drumgoole down to the newest office-boy everyone in the place was loaded for Stanley. I had a few choice gibes saved up myself, but I forgot them when I saw the boy. He didn’t look right. It wasn’t the court-plaster arabesques scattered about his face. It was something underneath the court-plaster.

“Hello, Curt!” he said as he came in. “Is the Old Man here?”

“Yes,” I said. “Glad to see you back, Stan. You turned the trick, eh?”

“Yes, I turned the trick — at a price.”

“Not so bad, either,” I observed, “at five hundred and fifty dollars.”

“I wasn’t thinking of the company,” he answered with a sigh. It was the first time I’d ever heard Stanley Carroll really sigh. Immediately he perked up and turned a grim sort of smile on me. “Nice, funny crowd of cute little jokers we keep about this place,” he remarked.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“Nothing much. Only, when I came in, three lever-pushers, waiting to answer to complaints, mewed. You’ll find the biggest one at the bottom of the stairs unless the others have carried him away. In the main office our handsome corps of pink and perfumed ledger-blotters were all busy earning their pay, to look at them; but a toy rat came out of a corner and buzzed around the floor real playfully. It’s waiting in my pocket till I can find the proper person to feed it to. The head bookkeeper is out buying a poultice. He made a mistake of licking his paw and pretending to preen down his fur when he saw me coming. Know of anyone else hereabout having some merry japes up his sleeve?”

“Why, Stan,” I said, “it isn’t like you to fly off the track this way.”

“Isn’t it? If you had lain awake six nights running, thinking — Never mind. Come in and keep me from murdering the Old Tad in case he says ‘cat’ to me.”

In we went, and Our Beloved President whirled around on his chair, stroked his whiskers and purred. I’ll bet he never knew how near he came to being a martyr to a sense of humor!

“Ah!” said he. “The hero of the catastrophe. The originator of the five hundred-and-fifty-dollar fee line.”

Stan was game. “Ha!” he said. “Ha!” said he, like a man paid to do it. “A joke is a joke, Mr. President, at times. And yours aren’t any worse than some I’ve given up gate money to hear. But what I want to ask is: Was that deal worth the money, or wasn’t it?”

To be good-natured for one whole minute at a time, even at someone else’s expense, wasn’t in Thaddeus B. Drumgoole.

“It wasn’t,” he snarled, all his meanness sticking out on him like a rash. “You ought to have had it for a fifth the price.”

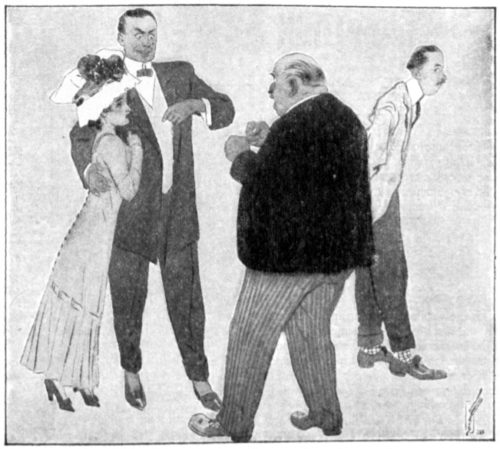

Stanley took one step forward. I went along, too, because I was hanging to his arm at the time. What might have happened next I don’t know. I saw the Old Man’s eyes fix, not on Stan, but on the door. Then I heard a very clear, self-possessed little voice say, “My entry,” and whirled around to see just about the daintiest and prettiest little five-foot-nothing of femininity that ever gave a man something to dream about.

“Mr. Drumgoole?” she inquired.

“That’s me,” admitted Taddles, giving her a winning smile that would have scared a fly off a bald head.

“I am Miss Massinger.”

“Pleased to meet you, Miss Massinger. Er — you may go, Mr. Curtis. And you, Mr. Carroll.”

“They may not,” countermanded the vision, looking at the head of the A. B. & C. with obvious disfavor. “I want your right-of-way man to hear what I have to say. You employ him, as I understand, to wheedle unsuspecting women out of valuable privileges. He thought he had done his work well this time, under pretense of — of —” Miss Massinger got pink and neglected to formulate the charge. “He’s mistaken. The farm was sold the day before the paper was signed.”

“Sold!” It was a trio by male voices.

“Here is your five hundred dollars. Fifty I retain for damages to my cat and my kitchen. Gentlemen” — accent on the first syllable — “I bid you good-day.”

“Oh, no, you don’t,” said Thaddeus B. Drumgoole, and I’ve never seen him look so vicious. “You’ll stay right here for the present. Sold the farm, have you, and then taken our money! Grand larceny, I believe they call that. Curtis, ’phone to Mr. Musgrove and tell him to bring a detective with him. Take a chair, my dear,” he added, leering at her with his little pig’s eyes. “We can’t afford to lose the pleasure of your company.”

She went quite white under his look. Instinctively she turned to Stanley, then hesitantly to me.

“Is it true, what he says?” she asked.

I nodded — and I hated to do it, too.

“I think you’d better go, Miss Massinger,” spoke up Stanley.

“And I think not,” sneered the Old Man. “Give me that paper, Carroll.”

Stanley didn’t, even look at him. “Are you going or not, Miss Massinger?” he asked impatiently.

“No, I’m not,” she retorted, and her little chin went up in the air, though the lips above it quivered pitifully.

He drew a cigar from his pocket. “I only asked because I want a smoke,” he remarked.

“You’ve grown very solicitous of my feelings suddenly,” she returned.

“Sorry I can’t return the compliment,” said Stanley. He took out the right-of-way document, scratched a match, applied it to the paper and, as the signatures blackened, curled and melted in flame before our eyes, held the fire to his cigar end and took a deep, satisfying whiff. Our Honored President rose from his chair with a sound like a broken-hearted toad. Miss Massinger fairly flew across the room and put her two tiny hands on Stanley’s big arm.

“What have you done?” she cried.

“I’ll tell you what he’s done,” squawked Old Taddles. “He’s destroyed our only evidence. He’s betrayed his employer like the dirty, low-lived traitor he is. He’s been bribed, that’s what! Bribed!” He stuck his ugly chin out and straddled over to her. “Was is money, my beauty?”

“If you’ve got to talk, Mr. President,” cut in Stanley very coolly, “talk to me.”

“I’m through talking with you.”

“Well, if you won’t talk, then listen.” Stanley drew himself up and stuck his hand in his coat front, in position for his swan-song of oratory. “Mr. President,” he said in his deep, rounded, professional voice, “I respect you for your scant gray hairs. As the head of a profitable, progressive and conscienceless corporation, I admire you. I honor and revere you as a ma e-factor of great wealth. But, unofficially between us two, and speaking as brother man to brother man, you’re a measly sort of a second-rate liar and chump, and if you were half your age I’d make over your outlines into something that more nearly resembled a human face!”

“You’re fired!” spluttered the Old Man.

“Again, you’re a liar!” said Stanley. “That makes two. Count ’em. I’m not fired. I’ve resigned. Here’s my resignation.” He scrawled two words on the back of the smoking paper and thrust it under the puffy Drumgoole nose. “Is it accepted or will you eat it?” he inquired sweetly.

What happened next I never could have sworn to before a jury, because I got awfully interested in a stalled auto outside the window at that moment. But I discerned a shaky sound to the reply, “Accepted,” as if it had been jarred out from between reluctant teeth. I looked around in time to see Stanley turn to the girl.

“Betty is the farm really sold?”

“Really. Was it very wrong?”

“Does the cat go with it?”

“Ye-e-e-s; if you say so.”

“Before you give up possession I’d like to sit in that inside room just once more,” he said, looking her full in the eyes.

The eyes fell. All the color that had gone out of her face came back and brought some more with it. “You’ll be welcome,” she said very softly.

And they went out together.

The offices of the A. B. & C. Interurban Trolley Company, Limited, have seemed dull and lifeless to me since then, except for one occasion. That was the morning that Old Taddles received the Massinger- Carroll wedding cards.

Featured image: Strike two, and the cat swearing at the umpire in four different languages. (Illustrated by Gustavos C. Widney)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now