He was born 150 years ago today, during the Ulysses S. Grant administration, and he died the year NASA was established.

Samuel Hopkins Adams’s millions of words must have reached just about every American during his life, whether through his muckraking journalism, short stories, romance novels, movies, poetry, histories, or biographies. He was a one-man Ford factory for the written word — in every form it could take — for the majority of his long life. But after he died, Adams’s legacy of documenting America’s evolving zeitgeist was relegated to archives and dusty libraries.

Adams’s broad career hasn’t garnered the same lasting attention of some of his contemporaries like William Faulkner, Ida Tarbell, or F. Scott Fitzgerald. He called his own writing “competent,” and others scarcely disagreed. But his mountain of work reveals in relief the humor and gravity of a modern society taking shape in the 20th century: principled antagonism to corporate corruption, sexual freedom, public health innovation, or just one 80-year-old man struggling to put on his socks.

Adams discovered his penchant for writing as a (mediocre and undisciplined) student at Hamilton College when he wrote up a critique of the faculty’s disciplinary actions and was expelled. He transferred to Union College in Schenectady, graduated, and then went to work for The New York Sun as a reporter.

At the Sun, Adams worked alongside a team of young, intrepid journalists scouring the city for its plentiful stories of class and race conflict in the Gilded Age. His use of newspaper writing to call attention to injustice and to hold power to account with hard-sought facts fit squarely with the evolving progressive, muckraking journalism of the era. Adams covered the Port Jervis lynching, the Buffalo switchmen’s strike, and countless other happenings on his night beat at the rough Jefferson Market Court.

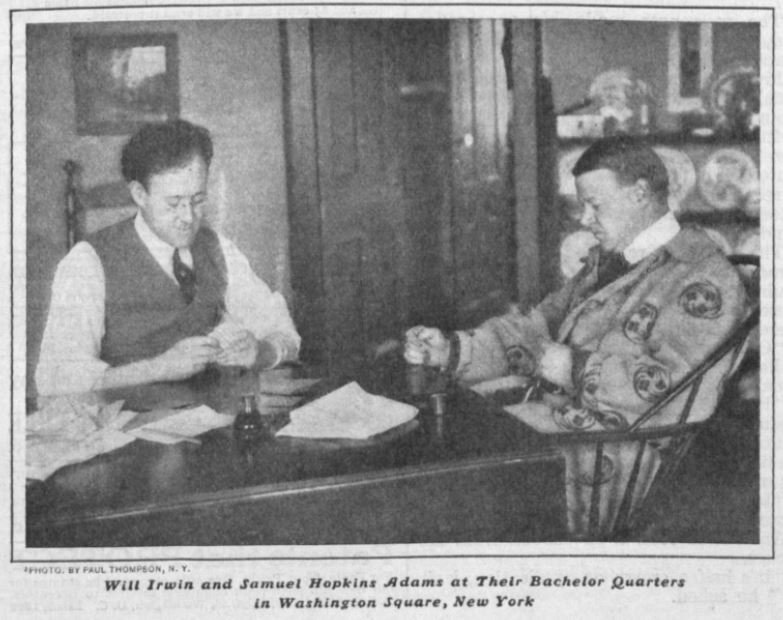

In 1900, he quit the paper to answer the clarion call of the longer art of writing and editing for magazines. While a managing editor at McClure’s Magazine, Adams also wrote for Collier’s, Scribner’s, and others about politics, crime, and labor crises around the country. The story of his career came after a few years: a public health investigation on preventable tuberculosis deaths that would develop into an influential exposé on patent medicines.

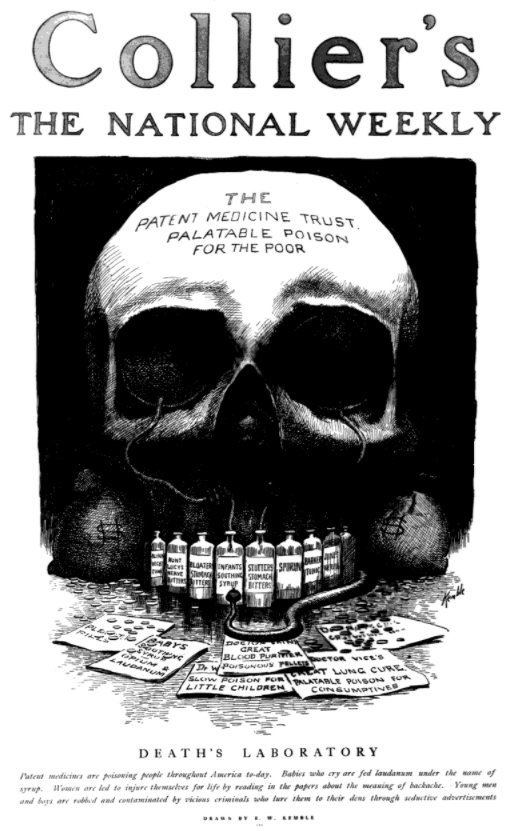

For decades, newspapers and magazines had advertised spurious ointments, elixirs, “blood purifiers,” and tonics that promised to cure ailments from nervousness to meningitis. Adams published a six-part article series in Collier’s titled “The Great American Fraud” that exposed the pseudoscience behind such patent medicines. His investigation found that the many “harmless frauds or deleterious drugs” were either ineffective non-cures or mixtures of alcohol and narcotics. Adams directed blame not only toward the companies that sold such products but also at publishers for advertising them (and protecting them by withholding bad press) and the government for stalling on regulation.

More than 20 years earlier, a consumer protection bill had been introduced in Congress to enforce better advertising and labelling, but it wasn’t until Adams published his series in 1905 (and Upton Sinclair published The Jungle the next year) that the Pure Food and Drug Act passed in 1906.

In the years to come, Adams sold short stories to loads of American magazines while continuing his muckraking journalism in Collier’s. As he was publishing mysteries, adventures, and fantasy stories, his magazine articles decried monopolization, deceptive advertising, and myriad other social problems. As Samuel V. Kennedy wrote in his biography of Adams, “His writing on public health, cancer treatment, and drug addiction was personal and sociological. In all, he displayed an idealism that Americans would right the wrongs if they knew the truth.”

Adams never stuck to a particular subject or wrote for a certain type of reader. If he found a story — or could invent one, as in his fiction — he typed it out. He wrote about chicken breeds for Country Gentleman, big cat trainers for McClure’s, and crabbing in South Carolina for this magazine.

In the 1920s, Adams began secretly publishing racy novels about flappers and bootleggers under the pseudonym “Warner Fabian.” In the foreword to his 1921 best-seller Flaming Youth, he wrote, “Women writers when they write of women, evade and conceal and palliate … men understand women only as women choose to have them.” F. Scott Fitzgerald credited the novel for promoting female sexual independence, and he referred to the popular film adaptation of Flaming Youth as the first and only authentic depiction of the sexual revolution of the Jazz Age.

Adams’s novels — as Fabian or otherwise — sold well, and much of his fiction made its way to the screen. His short story “Night Bus” was the basis for It Happened One Night, and his novel The Harvey Girls was adapted into a movie musical starring Judy Garland. In the ’20s, Adams was making 750 dollars per two short stories from this magazine.

The Adams word machine never stopped or slowed. Throughout his adult life, he would rise each morning at five o’clock and write until noon, with a goal of 1,000 publishable words. He published biographies on Daniel Webster, Peggy Eaton, and Alexander Woollcott; wrote histories on the Teapot Dome scandals, the Erie Canal, and the Warren Harding administration; and he kept writing novels, about small towns, newspapers, and labor struggles.

Adams’s writing was always reliably factual. At its best, it displayed his canny skill for telling subtle stories that revealed authentic American truisms one can only discover from experiencing the country’s many facets, as he did. His own curiosity about people and places guided his prose and his arguments in place of any rigid agenda. “I make hundreds of notes each year for possible use in historical novels,” he told The New York Times in 1945. “Did you realize that mosquitoes were suspected of carrying malaria more than one hundred years ago? Did you know that fingerprinting was talked about as a means of identification early in the last century? Did you know that the word ‘buncombe’ was first used in a laudatory sense?”

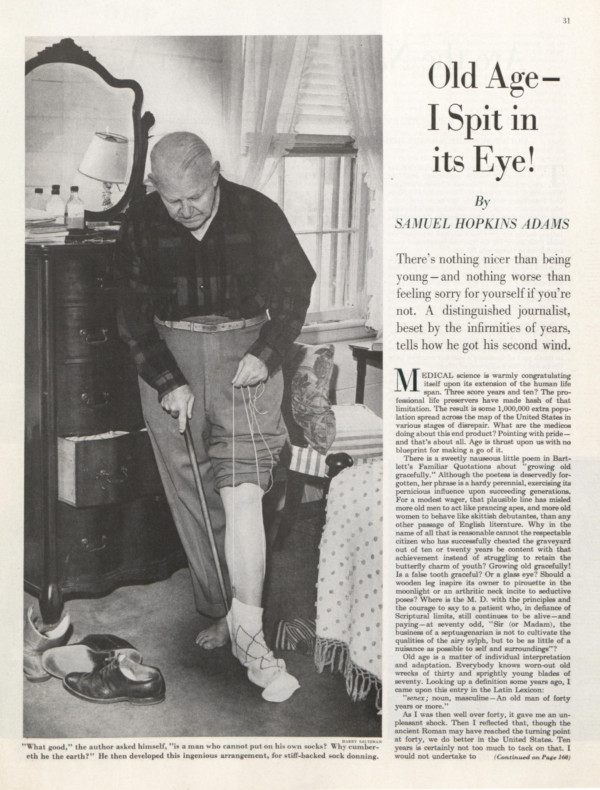

As he was nearing 80 years old, in 1950, Adams wrote an essay for The Saturday Evening Post about the prospect of utilizing the modern, longer lifespan afforded by modern medicine (“Old Age — I Spit in its Eye!”). He discusses his recovery from a hip surgery, after which “the surgeon cracked my shell and poured me out on the bed.” He was forced to learn to go up steps “sideways, like a crab” and seek the assistance of the carefree, able-bodied young. He even developed a contraption for the impossible task of putting on his socks in the morning. “For myself,” he wrote, “I do not want to be told to grow old gracefully; the process is tricky enough without throwing in any dance steps.”

His tale of the humiliations of aging is convincing and hilarious, and it might engender a curious interest in how the author came to tell stories so sober and yet colorful. Mostly, it makes one wonder how we could have forgotten about him.

Look for updates to the weekly classic fiction series for short stories by Samuel Hopkins Adams from the archive.

Featured image: Film Fun, 1922, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1907, The Boston Globe, 1904

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This man is truly fascinating on a multitude of levels. How often do we read of someone that possesses so much such knowledge on so many things, short of Ben Franklin? Almost never! He was kind of like the great general-interest magazines that flourished within his lifetime, personified in one person.

He’s a person I want to learn more about, and his writings on the various topics you mentioned here. He should NOT be forgotten, and I’m going to read his 1950 Post story per the above link for starters. I have to say I was pretty shocked by the 1905 Collier’s cover. This was NOT typical of their covers at all, with this particular one having a tabloid ‘shock value’. I want to read what I can of it though, because we can’t judge a book by it’s cover.

It was probably polarizing at the time, and they got a lot of letters regarding it. Mostly their covers were in the same vein as The Saturday Evening Post, and remained a popular magazine until its closing at the end of 1956.