The teenager is one of the more unusual inventions of the 20th century. Humans have been turning 13 for tens of thousands of years, but only recently did it occur to anybody that this was a special thing, or that the bridge between childhood and adulthood deserved its own name. The term teen-ager dates back to the early 1900s, but the word didn’t stick. Even until World War II, there are hardly any instances of teenagers in the popular press.

In the last few decades, however, the national media has nurtured a growing obsession with teenagers, in the sort of way that is neither lewd nor, perhaps, fully healthy. The press exhaustively tracks the apps young people use, the music they listen to, and the brands they follow. In the last few years, the fastest-growing large companies have been software and technology firms whose first adopters are often young people who know their way around a computer, smartphone, or virtual reality app. If most ancient cultures were gerontocratic, ruled by the old, modern culture is fully teenocratic, governed by the tastes of young people, with old fogies forever playing catch-up.

The teenager emerged in the middle of the 20th century thanks to the confluence of three trends in education, economics, and technology. High schools gave young people a place to build a separate culture outside the watchful eye of family. Rapid growth gave them income, either earned or taken from their parents. Cars (and, later, another mobile technology)

gave them independence.

1. The rise of compulsory education

As the U.S. economy shifted from a more localized agrarian society to a mass-production machine, families relocated closer to cities, and — at least initially — many sent their children to work in the factories. This triggered a countermovement to prevent kids from being forced to toil in mills.

The solution: compulsory public education for kids. Between 1920 and 1936, the share of teenagers in high school more than doubled, from about 30 percent to more than 60 percent. As young people spent more time in school, they developed their own customs in an environment away from work and family, where they could enforce their own social rules. It is impossible to imagine American teenage culture in a world where every 16-year-old boy is working jowl-to-jowl with his father on an assembly line.

2. The postwar economic boom

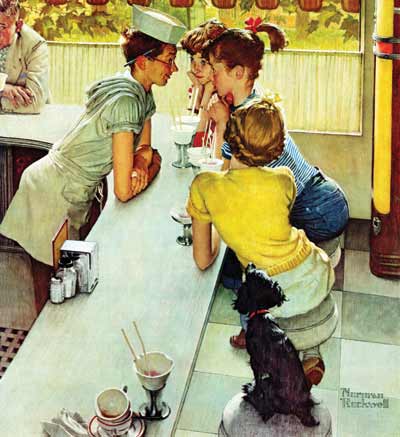

A serious commercial interest in teenagers didn’t begin in earnest until after World War II. To entice marketers, teenagers needed money, and that money would come from two principal sources: the labor force and parents. The 1950s saw one of the great periods of economic expansion in American history. With full employment came rising wages for unionized adults and older teenage workers.

Meanwhile, parents gradually had fewer children and spent more per child, as befits any scarce and valuable investment. Birth rates declined across the advanced world in the second half of the 20th century due to both the rise of female education and the legalization of the pill. Since the 1970s, the richest 20 percent of U.S. households have more than doubled their spending on childhood “enrichment,” such as summer camps, sports, and tutors. As the modern marriage has come to revolve around children, young people emerged as the chief financial officers of family spending.

3. The invention of the car

It might be a horrifying consideration for today’s singles, but a first date once meant an introductory chat in the living room with a girl’s parents. This might have been followed by a deliciously awkward family dinner.

But cars emancipated romance from the stilted small talk of the family parlor. Just about everything a modern single person considers to be a “date” was made possible, or permissible, by the invention and normalization of car-driven romance. The fear that young men and fast cars were upending romantic norms was widespread. The chorus of the 1909 Irving Berlin song “Keep Away from the Fellow Who Owns an Automobile” is instructive:

Keep away from the fellow who owns an automobile

He’ll take you far in his motor car

Too darn far from your Pa and Ma

If his 40 horsepower goes 60 miles an hour say

Goodbye forever, goodbye forever

If you think Tinder and dating apps are destroying romance today, you would have hated cars in the 1900s. Cars didn’t just hasten a historical shift from teenage codependence to independence. They fed the growth of a high school subculture. When buses could drive students farther from their homes, one-room schoolhouses gave way to large buildings filled with teeming hordes of adolescents and their hormones.

The fall of the farming economy and the rise of mandatory education combined to create a teenage culture that Americans viewed with deep anxiety. Fears of “juvenile delinquency” were bicoastal, inspiring Hollywood films, such as Rebel without a Cause and Blackboard Jungle, and galvanizing Washington subcommittees on the terrible problem of teens.

These forces conspired to unleash an abundance of leisure time, a temporal vacuum that teenagers filled with experimentation. “The abolition of child labor and the lengthening span of formal education have given us a huge leisure class of the young, with animal energies never absorbed by tasks of production,” wrote one New York Times critic in 1957. Even in the early years of their classification, teenagers were regarded as cultural nomads. Rather than settle into the established rituals of American society, they were roving vagabonds seeking out new frontiers of tastes and behavior.

Kids These Days!

Hand-wringing about American youth is nothing new.

The problem with teens is that, well, they’re just a pain in the you-know-what and always have been. With all those wild hormones surging, and little of the self-control that a mature person naturally possesses, they’re bound to cause trouble, as these 20th-century excerpts from our pages reveal.

We Made It Too Easy for Them

What could have happened 40 years ago that took the stamina out of the men and women who were to become the parents of these amorphous youths whose accent of conscious superiority indicates so clearly immature minds? We ourselves had lived as pioneers, abstemiously, obediently, with few pleasures, and under hardships that produced strength of character. The idea was to give our children more happiness and a better chance. We have made it so easy for them that too many of them have become unfilial and egotistical.

But these young people are of the same stock that wrought a civilization out of a wilderness. The recent panic sent some of them to work, and what sends all of them to earning their bread will not be a panic — however it looks on the ticker — but a national blessing.

—“Parents and Children, Yesterday and Today” by Corra Harris, May 28, 1932

Lost Generation

The 5 million kids who were between 10 and 13 years old when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor six years ago are a lost generation and are rapidly becoming America’s major sociological problem. Everywhere on applications the classification “Check here if a veteran” haunts them.

Because they were born too late to fight, the feeling of not belonging has created a serious morale problem for the lost generation. Accustomed during the war to his own spending money and a feeling of social independence, the young nonveteran today finds himself literally an outcast.

The need for some kind of immediate action is pressing. The lost generation asks only for the chance to belong.

—“Our ‘Lost Generation’ Wants to Belong” by Arnold L. Horelick, August 2, 1947

Rush to Judgment

“Boys will be boys,” we used say, when the neighborhood kids jumped on the back end of the streetcar and pulled the trolley off its overhead wire. We said it again when they broke out with a black eye after a fight behind the barn. Now all the neighborhood kids are juvenile delinquents, whether they belong to the switchblade set under the Brooklyn Bridge or to the baseball team that plays in the Smiths’ empty lot at the corner of Elm and Pine. … Granted, juvenile delinquency — especially in our cities — is a serious problem, but why continually drag in that dispiriting phrase every time a teenage activity is mentioned?

—“You’d Think It Was Unconstitutional to Be a Teenager” by Carol Spicer, September 20, 1958

Teen Spirit

“Our youths now love luxury. They have bad manners, contempt for authority, disrespect for older people. Children nowadays are tyrants. They no longer rise when their elders enter the room. They contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble their food, and tyrannize their teachers.”

This remark sounds like the beginning of a letter to a metropolitan newspaper or the lament of an old-fashioned parent of the 20th century. In fact, it was made by Socrates in the fifth century B.C.

Are these comments any more valid now than they were in Socrates’ time? I am inclined to think not. What the young person of today needs above all else is peace — peace with himself. Most of them, left alone, come to some sort of armistice with themselves sooner or later, but one is never sure that hostilities are over. This sort of peace involves recognition; and it is our job as teachers and parents to see that this recognition comes in a way which will lead to happiness in the future.

—“Why Do They Misbehave?” by Edward T. Hall, September 10, 1960

In 1953, J. Edgar Hoover published an FBI report warning that “the nation can expect an appalling increase in the number of crimes that will be committed by teenagers in the years ahead.” The message reverberated in Congress, where President Dwight Eisenhower used his 1955 State of the Union to call for a federal legislation to “assist the states in dealing with this nationwide problem.” Fredric Wertham’s international bestseller Seduction of the Innocent relied on sketchy forensics and hysterical prissiness to argue that comic books were a cause of juvenile delinquency. On the one hand, Wertham’s consideration for art’s influence on young people is noble in the abstract. But his specific recommendations were priggish in the extreme; he complained, for example, that Superman was a fascist and Wonder Woman turned women into lesbians. He called comic books “short courses in murder, mayhem, robbery, rape, cannibalism, carnage, necrophilia, sex, sadism, masochism, and virtually every other form of crime, degeneracy, bestiality, and horror.”

As soon as teenagers were invented, they were feared. Many social critics made no distinction between the young car-jacking thieves and the comic readers. To an old worrywart, they were all feral gypsy sprites.

The last 60 years have made teenagers separate. But are they really so different? Or are teens just like adults — but with less money, fewer responsibilities, and no mortgage?

There is some evidence that, as many parents quietly suspect, teenagers are chemically distinct from the rest of humanity. They suffer uniquely from loosely connected frontal lobes, the decision center of the brain, and an enlarged nucleus accumbens, the pleasure center. So where adults tend to see the downsides of risky behavior in high definition, teenagers see the potential rewards as if projected onto an IMAX screen with surround sound. The result is sadly predictable: Teens take more risks and suffer more accidents. Americans between 15 and 19 have a mortality rate that’s about three times higher than those ages 5 to 14.

For Laurence Steinberg, a career investigating the teenage mind started with a common observation that is self-evident to parents, teachers, or anybody with even the faintest memories of high school: Teenagers often act dumber around other teenagers. Steinberg, a psychologist at Temple University, put people of various ages in a simulated driving game with streets and stoplights. Adults drove the same, whether or not they had an audience. But teenagers took twice as many “chances” — like running a yellow light — when their friends were watching. Teenagers are exquisitely sensitive to the influence of their peers. The precise definition of coolness may change over time, from cigarettes to Snaps, but the deep, animal need to possess it does not.

But what is coolness, anyway? In sociology, it is sometimes defined as a positive rebellion. It means breaking away from an illegitimate mainstream in a legitimate way. That might sound like a fussy definition. But it has its uses. My high school had a dress code, and when you’re 14 years old, violating a repressive clothing regime is a beautifully obvious way to signal to other kids that you’re noncompliant. But not always. What about sagging your slacks at a school memorial for war heroes? Or proudly untucking your shirt at a funeral for the school’s favorite teacher? The same group of people can consider an outfit cool or deeply disrespectful, depending on how legitimate people view the norm that it’s violating.

At the end of the 20th century, many teens gravitated to logos. The long economic expansion from the 1980s and the 1990s gave them the means to spend lavishly on clothing emblems. A fashion hit like Ralph Lauren was based not only on the quality of the garment, but also on the logo’s talismanic power in high school hallways.

In recent years, the smartphone screen displaced the embroidered logo as the focal point of teen identity. It was once sufficient to look good in a high school hallway, but today, Snapchat, Facebook, and Instagram are all high school hallways, where young people perform and see performances, judge and are judged. Many decades after another mobile device, the car, helped to invent the teenager, the iPhone and its ilk offered new, nimble instruments of self-expression, symbols of independence, and better ways to hook up.

And so, in half a century, teenagers went from being a newfangled classification of awkward youth to an existential threat to American security to a valuable consumer demographic and a worthy topic of research. Teenagers are the market’s neophiles, the group most likely to accept a new musical sound, a new clothing fashion, or a new technology trend. For adults, especially those with power and money, the rules are what keep you safe. When you’re young, every rule is illegitimate until proven otherwise. It is precisely because they have so little to lose from the way things are that young people will continue to be the inexhaustible motor of culture.

From Hit Makers by Derek Thompson, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright 2017 by Derek Thompson.

Derek Thompson is a senior editor at The Atlantic magazine, where he writes about economics and the media and is a regular contributor to NPR’s Here and Now.

This article is featured in the January/February 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

What a fascinating exploration of the evolution of teenagers throughout history! It’s interesting to see how societal changes have shaped the identity and experiences of youth. I particularly enjoyed the anecdotes about the different cultural milestones that have influenced each generation. Thank you for shedding light on such an important topic!

This article really sheds light on how the concept of “teenagers” has evolved over the decades. It’s fascinating to see the societal changes that have shaped youth culture and identity. I loved the examples you provided — it makes me reflect on how different things were compared to today’s world. Thanks for this insightful read!

This was such an insightful read! I had no idea how much the concept of being a teenager has evolved over time. The historical context really adds depth to our understanding of youth culture today. Thanks for sharing!

What a fascinating exploration of how the concept of being a teenager has evolved over the years! It’s incredible to see how cultural, social, and economic changes have shaped the youth experience. I especially loved the section about the emergence of the teenager as a distinct social group in the 1950s. It really makes you appreciate the complexities of adolescence today! Thank you for sharing this insightful piece!

curiosity may have killed the cat but made the teenager and a poodle skirt,sock hop ball whatever that is.

i loved your essay, it was great

This is so true. Being a teenager myself, I can definitely agree with almost everything that is said here. We are indeed on of the most targeted audience for almost any product. I just never realized why, I always taught that it was just because we were the ones who made our parents buy the things.

But now I realize, after reading this, that it is true that we are more open to new things, new experiences than the older generation. And it only makes sense that the companies target us to make their “new and innovative” products a success.

This is so true. Being a teenager myself, I can definitely agree with almost everything that is said here. We are indeed on of the most targeted audience for almost any product. I just never realized why, I always taught that it was just because we were the ones who made our parents buy the things.

But now I realize, after reading this, that it is true that we are more open to new things, new experiences than the older generation. And it only makes sense that the companies target us to make their “new and innovative” products a success.