“The Undecided Blonde” by Timothy Fuller

Summer is for steamy romance. Our new series of classic fiction from the 1940s and ’50s features sexy intrigue from the archives for all of your beach reading needs. In “The Undecided Blonde,” Hannah is surprised when her past lover Hank, a playwright, turns up to reignite their romance. Her new man, Tom, isn’t so keen on the idea. The 1955 short romance by Timothy Fuller features a classic love triangle with Hollywood types in a small town.

The town of Santuxit, Massachusetts, was just as quaint as Purdy expected. There was a tiny park with old white houses crowded up around it and an ancient church at one end. It was snowing, and each vista was like a Christmas card before they went arty.

Purdy pulled into an early-colonial gas station in the center of town and was surprised that the pumps weren’t finished in knotty pine.

“Say, Mac,” he asked the attendant, “which way to the chowder factory?”

“Yonder,” said the man. “Quarter mile out on the Nubbin Road.”

So Purdy took the Nubbin Road and, sure enough, there was the factory. It had once been a railroad station, but now there was a sign in antique letters reading: The Chowder Works.

“Crickey,” said Purdy.

He’d make this the shortest interview on record just grab the facts and be back in Boston by dinnertime. The place was open, aromatic, neat and, so he thought, empty. It wasn’t until he looked through the grilled window of what had once been the ticket office that he saw the blonde on the cot in there. She was on her back with one arm thrown over her eyes but despite this obstruction the total effect was promising. The chin was good, the lips generous, and what he could see of the nose was upturned. Although Purdy ranked jeans with middy blouses as unimaginative female attire, this pair was well filled and, below, the ankles were nicely fashioned. Also she hadn’t followed the current trend of hacking off her locks with dull shears. Her hair was the color of copy paper left a day in the sun, and it was long, soft and intelligently curled at the end.

Why rouse her, Purdy asked himself. She would then talk, and no talk from a girl whose career was chowder making in an abandoned coastal-railway station could amount to anything. Purdy knew For months now he’d authored that popular newspaper series entitled Your Enterprising Neighbors and few of the neighbors, once away from their enterprise, had proved swift with their dialogue True the twelve-year-old who manufactured seat covers for English bicycles out of imported tartan and the little old lady who knitted bottle socks in your favorite college colors had been full of worldly wisdom, but from the dreamers in between — the gadget and toy makers, the bird fanciers and animal trainers, the jelly brewers and herb gardeners, the clothing designers and all the strange highway entrepreneurs — frankly nothing of interest or value.

On the other hand, Purdy reflected, resting his elbows on the ledge outside the ticket window, this doll might not even work here. His information gave the proprietors of the chowder pitch as two ex-New York City typists who had fallen in love with the area while vacationing the previous summer. This girl looked far too young and unjaded to be a party to any such bucolic deal.

As usual when contemplating a new girl, Purdy allowed his imagination to roam at will. Let’s say it’s low tide, he assumed. The typists are out on the flats in their hip boots, digging tomorrow’s clams, and the blonde here is a niece of one of them. She’s half a year out of Yale Dramatic School and is on for the winter to live frugally and finish writing her play. She’s been up all night with the third act and is worn out and depressed. More than anything else right now she needs advice and encouragement. When she wakes up we’ll seek out some quiet local bar and —

“Hello, Hank,” said the girl, and sat up.

Only the eyes were familiar. They were green, and he was certain at one time in his past he had looked deeply into them, but no bell sounded.

“Madam,” he said, bowing, “you have me at a disadvantage.”

She advanced, laughing, to the grille. “This is your life, Henry Purdy,” she said. “It is June and we are dancing. You are twenty-one and full of great plans for yourself. You will have three hit plays running on Broadway and then you will return to claim me as your bride. I am fourteen and almost believe you. We are in Miles River, Indiana, where you are best man at my brother’s wedding.”

“Hannah Willoughby,” he said, awed. “For it was she.”

“The same.”

He rattled the grille, but it was immovable. “Come out of there, Hannah Willoughby. I desire to kiss you.”

“A splendid idea,” she said, and hurried around through the door.

But he didn’t kiss her. He shook her hand and patted her shoulder, because she was no longer fourteen and she was Horace Willoughby’s kid sister and Purdy had his code.

“Don’t tell me you’re mixed up in this clambake, Hannah,” he pleaded. “The letter I got was signed by a Carlotta something.”

“My former partner. She thought we could use the publicity. But Carlotta went back to New York ten days ago. Claimed she was getting cabin fever. She was sleeping in the baggage room, and it has no window, so — ”

“You live here?”

With her thumb she indicated the ticket office. “Tw o windows. Inside and out.”

“Does Horace know? Won’t he send you fare to get back home?”

“This is a nice little racket, Hank,” she informed him, bridling. “Right now I ‘m clearing fifty dollars a week.”

“Gad,” he said. “And Carlotta gave up her share in this? She must be out of her head.”

Her chin went out, and with it her fine full lower lip. She looked as if she might readily sock him.

“I jest, Hannah,” he said quickly. “ That is Purdy’s way when confronted with imponderables. Believe me, I ‘m an expert in these undertakings, kid, and yours looks sound enough. Sloth alone can keep you from rolling in riches.”

She was mollified. She led him happily around the pots and pans, explaining the intricacies of the plant’s operation. It appeared that she and Carlotta had stumbled upon the fact that no real, fully flavored, old-fashioned clam chowder was commercially available. The catch, they’d discovered, lay in the nature of chowder itself. To be right, it had to be fresh. Why not, they’d reasoned, make up a concentrate of the essential ingredients, lacking only scalded milk, and deliver it fresh to institutions like schools, colleges, hospitals, clubs —-

“Take schools alone, Hank,” she said, with fire now in her wild green eyes. “You’ve heard of the hot-lunch program? Do you realize that within a radius of forty miles of where we now stand there’s at least a hundred thousand school children who must be fed something at noon five days a week?”

“I t’s shocking,” he admitted. “Do you feed all of them all by yourself?”

“Oh, I don’t do it alone. Mrs. Pina comes in mornings to help with the potato dicing, and Charley Shaw shucks clams and drives the truck. We haven’t really touched the potential market, Hank. This could be big!”

He nodded sadly. She was an excellent girl, marred only by the eternal dream of easy wealth. But he had a nice gimmick for his story: Hoosier shows Yankees way to make clam chowder.

“Do you know quahogs?” she asked, holding out a large brown mollusk for his inspection. “ They’re the big brother of littleneck and cherry-stone clams. They live to be thirty years old. The Latin name is Venus mercenaria.”

“A very pretty name,” he said. “A pretty name for you perhaps. Do you ever get out of here? Do you ever have fun?”

“Fun,” she said, and sighed. “That’s you, isn’t it? The fun-loving Purdy. Hankus comicus. Yes, I have fun, Hank. For one thing, I ‘m getting married next month.”

He felt a short, inexplicable spasm in the pit of his stomach, but at once it was gone. All pretty girls grew up and got married. It was in the nature of things. In time, no doubt, he’d get married himself.

“Well, that’s fine, Hannah. Congratulations. Is it anyone we know?”

“His name is Tom Burnett. He’s a veterinarian here. You could meet him, but he’s gone to a meeting in Worcester to read a paper tonight on wood ticks. They get on dogs, you know, and Tom is working on a permanent repellent.”

Purdy couldn’t help himself. “My,” he said, shaking his head. “And there I was thinking you might not be having fun!”

“Very amusing,” she said, and smiled. “ I was about to ask you to stay and eat some lobster with me because there’s something I want to talk to you seriously about, but if ——-”

“Hannah,” he said, “ if there’s something you want to be serious about, I promise to stay and eat your lobster. Is there anything we might need to go with it? Beer, wine, whisky, brandy?”

“I don’t drink,” she said, but he shot her a stricken look and she giggled in spite of herself. “Ordinarily, that is. Oh, Hank, it is good to see you again, and it’s a long cold winter. I’ll write you a list.”

He took her list and found a remarkable store that carried newspapers, drugs, hardware, groceries and a splendid selection of grain and malt beverages. It was run by a laconic character actor in a hard straw hat who thawed a bit under Purdy’s final extravagant purchase of a pint of cognac.

“Tell me,” Purdy asked casually, as he counted his meager change, “who’s the best veterinarian here in town?”

“Doc Burnett.”

“Good, steady man, is he?”

“None steadier. Tom’s been at it now for more’n thirty years.”

Purdy reeled. Thirty years! Why, the man must be nearing sixty, and Hannah, Horace Willoughby’s sister, planned to marry this ancient!

It was all too clear how the match had transpired. Hannah, lonely, far from home, fatigued by her effort to maintain her precarious enterprise, had been carried away by the promise of security and an easy, well-ordered existence with the stolid doctor. It happened every day. Venus mercenaria, indeed.

Driving slowly back through the snow to the factory, Purdy probed deeply into his conscience. Am I, he demanded, old Horace’s little sister’s keeper? What right might I have, if such were possible, to throw a wrench into this mishmash? Do I have a duty here? Or should I keep silent, eat my fill of lobster and slink guiltily away?

He arrived back at the station in a state of flux. In his absence, Hannah had changed her clothes. She had selected a pink blouse, a flaring black satin skirt and golden ballet slippers. She had also combed out her long yellow hair, brightened her mouth and anointed herself liberally with an exotic perfume. The total effect, when she pirouetted for his inspection, was sufficiently charged to cause Purdy to avert his eyes. Clinking with his supplies, he crossed to the counter.

“Hannah, child,” he said, “this serious talk you proposed. Let’s get on with it.”

“O.K . But promise me one thing. Hank. Don’t get sore.”

He laughed easily. “You’ll find I compare favorably in composure with jolly old Saint Nick.”

“Very well, then. Hank, you’re twenty-seven years old; right?”

“Right.”

“You’re bright, witty and talented.”

“All three. Also generous, kind “

“Hank, how many plays have you written?”

He was in the act of removing a bottle by its neck from a paper bag, and now saw his knuckles gleam white. With masterly control, he lowered the bottle gently to the counter and released it.

“To give you a rough total, dear,” he said, “none.”

“You were always going to, weren’t you?”

“A childish whim,” he said easily. “A passing adolescent fancy.”

“Hank,” she said relentlessly, “you’re a liar.”

He was, he felt, equal to the challenge. “ I trust you’re aware, Miss Willoughby, that lobsters are readily procurable all along this coast. Even now some local Boniface is awaiting my custom. I don’t have to take this obloquy from you, a mere chit of a chowder maker.”

“Oh, Hank!” she said and clapped her hands. “Don’t you see? You even talk like a play! You can do it, Hank! All you need is free time, a quiet place to work with no distractions, and a steady income coming in each week! That’s all!”

“Aren’t you forgetting paper and pencils?” he asked, and laughed hollowly. “Those I might be able to supply.”

“You don’t understand,” she said. “Hank, I want you to have this!”

He frowned. Her hands were at her sides and he was at a loss as to precisely what she was offering him. “This?”

“Yes. The chowder works.” Her right hand now waved vaguely at the pots and pans. “Charley and Mrs. Pina could do most of the work, and all you’d have to do is supervise it. Even if you didn’t want to expand, you’d have enough coming in every week and — ”

“Hannah,” he said carefully, “ I am deeply moved.”

A work stool was handy and he drew it up.

She swallowed and her eyes went misty, turning them a shade toward blue. “Well, you were Hod’s roommate in college, and you were nice to me at the wedding, and I want to see you get ahead.”

As ye sow, Purdy thought, so shall ye reap. But he didn’t say it. In the first place, this was no time for another joke, and in the second, he had no great trust in his voice. That this wonderful girl should be pledged to a doddering quack —

“Anyway,” she said, “Tom doesn’t want me to work after we’re married, so you’d better have it.”

Tom, Purdy thought suddenly, won’t be in a position to make such highhanded decisions much longer. Old Tom doesn’t know it, but he’s about through.

It would take time, of course, and plenty of skill. He could hardly hope to lay more than a groundwork this first evening. Tonight would be devoted to brief exploratory maneuvers. After all, he knew next to nothing about this girl, and success would require a complete dossier of her innermost self. Obviously, loyalty meant much to her, hence she’d not lightly abandon this rustic V.M.D.

“Well, partner,” he said, getting up from the stool, “let’s at least have a drink while we talk it over.”

“I feel like one,” she said eagerly. “Hank, this is swell!”

He smiled. Drink, carefully apportioned, could be a handy tool.

“Bourbon?” he inquired casually. On the rocks?”

“Whatever you say.”

Up to and including the lobster, it went very well. Rarely, Purdy had to admit, had he been in better form. He amused her with anecdotes from his college days with Hod, touched modestly on his experiences in Korea, and shocked her mildly with some aspects of his present Bohemian existence on Beacon Hill. In general, the format was meant to instill confidence in himself as a fundamentally sound human being, while doubts grew as to the scope, color and excitement that would be hers, wed to the aged vet.

But while he was preparing two generous cafe diables, Hannah flung an arm about his neck and kissed his cheek.

“Careful, doll,” he said, sensing no danger. “This coffee is hot and the brandy dear.”

“Oh, the heck with that,” she said, and kissed him again, nearer the mouth.

He abandoned his drink making, disengaged her arm and looked clinically into her eyes. Both of them appeared to focus normally.

“Venus, baby,” he asked with some concern, “how do you feel? You’re not getting crocked on me?”

“Hankus pankus,” she said happily, “ I ‘ve only had two little drinks, and that was before supper. I just feel good, is all. Maybe I have a wee touch of cabin fever. What do you think?”

This possibility had not occurred to him. It-might well be the answer, and if so, it required delicate handling. He wanted her to have no remorse following this night’s session. It would be well for him to remember that this presently gay girl was also capable of conducting a going chowder concern, and for her to suspect, in the morning, that he’d taken any advantage would be ruinous.

“You know something?” she asked, and crinkled her nose at him. “You broke a promise to me. When you first got here you said if I came out of the ticket office you’d kiss me.”

“True,” he admitted. This much, properly executed, could do no harm. He extended his arms. “Advance, Hannah Willoughby.”

“Catch me,” she proposed, and went up on her toes.

Very well, he thought, this lighthearted mood is excellent.

She led him a merry chase, indeed. Here a frying pan clattered to the floor, there a pile of cartons toppled. At last, panting, he cornered her by the baggage-room door. She struggled briefly; then went limp and tipped up her chin.

He achieved, Purdy felt, just the right balance between comedy and lust. It was a token, really. No remorse could properly ensue.

“Old Hankus,” she said and her eyes were fading once again into blue. “You’re not so comicus, after all.”

“Honey,” he said nervously, “I think it’s time you told me a bit more about your Doctor Burnett.”

He retired to his stool, but she followed and sat on his lap.

“You’d like him,” she said, and touched his right cheek. “You’ve got lipstick all over.”

He ignored this diversion. “But what’s he like?”

“Oh, he’s New England, I guess.” She put her head on his shoulder, and the perfume of her hair was strong upon him. “Steady, straightforward. He was a nine-letter man at Cornell.”

That would account for his vigor, Purdy mused. Still in those days the competition was less.

“Did you win your letter in college, Hankus?” she asked, and nuzzled his neck.

It was then that a great white light flashed on in Purdy’s mind. She had no intention at all of marrying this Burnett. The vet was a decoy, a ruse, to arouse his jealousy. From the moment he stepped into this chowder mill she’d been playing him for all she was worth. What a rube he’d been to fall for it.

But why? What could she want from him? Marriage, of course. They all wanted that. Oh, there might have been a lingering romantic notion left over from Horace’s wedding day, but he was here on trial. She was looking him over. Why, she had actually sent for him. Carlotta might have written that letter to the paper, but you could bet it was little old scheming Hannah, who put her up to it.

Well, Purdy, what now? A moment ago ‘ you were prepared to marry her, weren’t you ? Desired to, didn’t you?

But the situation is quite different, he argued. Before, we were more or less faced with a crisis here. Now cooler heads can prevail. Are you really ready for marriage? For all its problems and responsibilities? You’re young, boy. Twenty-seven is nothing.

Well, we’ll cross that little bridge when we come to it, he decided sagely. Meanwhile

“Why, yes,” he said, moving her head into a kissable position. “I won my letter in this.”

He kissed her truly and well.

“Now, Hank!” she gasped, twisting away. “Let’s keep this comicus, shall we? Remember, I —-”

This time, as a variation, he kissed her well and truly. She socked him. It was a glancing blow, but it brought water to his eyes.

“I ‘m sorry, Hank. I guess it’s my fault, but I didn’t think you’d do anything — like that. We were having fun and—-”

“Oh, come now, Miss Willoughby.” He grinned at her, holding both her hands.

“No, really, Hank. Let me go. I — oh, golly Moses!”

He followed her eyes to the door and saw it open to admit a small cloud of snow and one large young man in a hunting cap and red-checked woolen jacket.

“Tom,” Hannah whispered. “Why aren’t you in Worcester?”

Purdy froze, but apparently. the man’s eyes were still dazzled by the light.

“They have fourteen inches of snow already west of Boston,” he said. “They canceled the meeting.”

“What about your office hours?” she asked desperately.

“Dad’s taking over tonight. I thought I’d just drop by.” Dad, Purdy thought, old Dad Burnett, the best veterinarian in town. By now, the eyes of the young, the real, Doc Burnett had grown accustomed to the light. Slowly, painstakingly, he detailed the mass of damaging evidence. The bottles, the toppled cartons, Hannah’s tousled hair, Hannah’s lipstick on Purdy’s face.

In a way, Purdy had to hand it to him. They didn’t come any straighter than young Tom Burnett.

“Beat it,” the doctor said.

Purdy couldn’t recall ever having encountered a more massive vet. Clearly, two courses lay open to him: he could go quietly in one piece, or violently in several. He stood up, still undecided.

“This is Hank Purdy, Tom,” Hannah said wildly. “He was my brother Horace’s roommate in college. He — he’s lots of fun!”

It was this line of defense that decided Purdy. For far too long now he’d been lots of fun.

“I believe I’ll stay,” he said, meeting Burnett’s steely eye. “Shall we settle it in here or do you want to step outside, doctor?”

“Outside,” said Tom, obviously a man well accustomed to lightning decisions of this nature.

“Right,” said Purdy. “Take off your mackinaw.”

There was something almost tragic in the manner in which Burnett divested himself of his outer garment. How slowly each arm came out of the coat, how careful the folding, how deadly the light dropping of the cap. He’ll clobber me, Purdy thought. But he stepped outside.

The snow fell, the light was poor and the footing insecure. Let it be swiftly done, Purdy prayed; let one blow decide it.

It did. Burnett closed in, arms cocked, and Purdy shot out his right fist. He felt a stabbing pain along his arm, and saw the hulking form collapse at his feet. Burnett lay as though dead.

I’ve killed him, Purdy thought. The fellow’s foot must have slipped and he fell into my fist, but it’ll be manslaughter at least.

He dropped to his knees and rubbed snow feverishly on the face of the inert body. Miraculously the eyelids flickered.

“Nice punch,” said young Tom Burnett. He worked his chin with his hand. “Fractured again. Never should fight. They warned me. You win, Purdy.”

Suddenly, for Purdy, this chance victory was soured by remorse.

“Doc,” Purdy said, “you misread the picture in there. Hannah’s true blue. I played on her loneliness, plied her with liquor——”

“What’s done is done,” said Burnett. “Such things can’t be mended.”

“Give me a moment to say good-by to her,” Purdy pleaded. “ I ‘ll make things right for both of you.”

He stood up and hurried back to the door. It opened for him and he narrowly missed falling flat on the floor.

“Oh, Hank,” Hannah said. “He hurt you.”

“He may have broken my hand,” Purdy admitted, regaining his balance. “Hannah, listen to me. You’ve got a great guy out there. Go to him now. He needs your sympathy.”

“But, Hank —”

“I ‘m going to run along now, baby. We had our laughs, and the lobster was fine. Give my best to Hod when you write.”

“But, Hank — ”

He brought his undamaged hand to his lips and blew her a kiss. “So long, Venus. You’re the best.”

“The play, Hank. Won’t you —”

He smiled wryly and reached out and rumpled her hair. “ I’ll write that play, kid. I’ll send you tickets for the opening night.”

He lounged for a moment against the door. He felt great. He felt like Gary Cooper in the last scene of a socially significant Western drama. He only wished he had a cigarette drooping from his lip.

She socked him again. This time it was harder, and it staggered him.

“Oh, what a faker you are!” she railed. “Six years ago you said the same thing — and what happened? Nothing! Go on! Get out of here! Beat it!” She was weeping.

He put his arms around her. He kissed her forehead, her nose and both damp eyes. It was all very curious. He saw that Burnett had silently entered, retrieved his cap and coat and as silently departed.

“Oh, Hank, darling,” she sobbed, “I didn’t really mean that! I don’t care if you ever write a play or not! I don’t! I guess I don’t know what I do want!”

“I know,” he said, feeling wise beyond his years. “ It’s sometimes hard to tell.”

“Tom is so nice,” she sniffed, “but honestly he’s not much fun. Not like you. Promise me you’ll always go on having fun.”

“I can manage that,” he told her. “With you I’m a cinch.”

“Then you’ll stay and take over the chowder business?”

“I’m taking everything over. The works.”

“Oh, Hankus,” she sighed. “That’s lovely.”

It truly was.

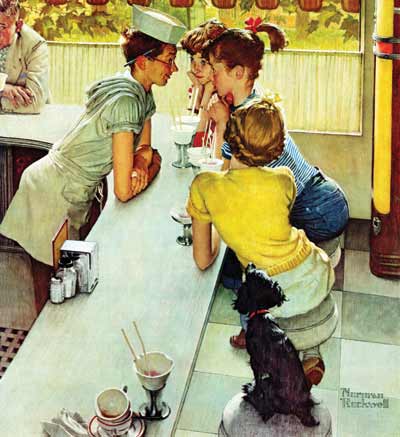

The Rockwell Files: Best Job Ever

Rockwell’s inspiration for this August 22, 1953, cover illustration grew out of stories his son Peter told of working a soda counter one summer. Peter even posed as the young man when Dad painted the scene. When his father showed him the final product, Peter didn’t like it. He claimed he “wasn’t that goofy looking.”

In an earlier draft of the illustration, the counter was more crowded. A gentleman’s balding head was visible in the foreground, and a mother and son sat at the far end of the counter. But Rockwell removed them so he could draw viewers’ attention to the mid-canvas drama, where a boy and three girls stare at each other across a counter with rapt attention.

As always, Rockwell adds numerous masterful details, like the reflection of the sugar dispenser in the napkin holder, the grated floor that would prevent slipping on spills, and the vintage Wurlitzer jukebox just visible at the right edge. And that man in the corner? We can pretty easily guess what he’s thinking: Hot fudge! Ice cream! Girls! Why weren’t there summer jobs like this when I was young?

This article is featured in the July/August 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Your Weekly Checkup: Is Air Pollution Affecting Your Health?

“Your Weekly Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

Information collected by the World Health Organization (WHO) from 4,300 cities in 108 countries indicates that 9 out of 10 people breathe air that contains high levels of pollutants, which are responsible for 7 million deaths annually. The pollutants are a complex mixture of solid and liquid droplets containing sulfates, nitrates, carbon, and other toxins that are inhaled into the lungs with each breath.

Outdoor air pollution contains thousands of components derived primarily from cars, industry, power generation, and home heating using oil, coal, or wood. Such pollutants can lead to health problems including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, blood clots, strokes, inflammation, and heart disease, mainly coronary artery disease.

Pollution concentrations often vary during the day, depending on weather conditions such as wind direction and speed, temperature, and sunlight that affect chemical reactions that produce toxins such as ozone. Traffic-related pollutants, like ultrafine particles and soot, often peak during the morning and evening rush hours, causing high exposure for commuters.

Even though people in most Western societies spend about 90% of their time indoors, predominantly in their own homes, outdoor air pollution infiltrates buildings, and most of the exposure typically occurs indoors. The problem is especially prominent when solid fuels are used for cooking and heating, or from cigarette smoking in the home.

More than 80% of the world’s population lives in areas in which particulate matter reaches or is above thresholds recommended by the World Health Organization. The WHO data show that U.S. cities on the polluted list include Los Angeles, Bakersfield, Napa, Calexico and Fresno, California; Indianapolis and Gary, Indiana; Louisville, Kentucky; and St. Louis, Missouri. More than 40% of the world’s population does not have access to clean cooking technology or lighting, making travel to cities like Peshawar and Rawalpindi, Pakistan; Varanasi and Kanpur, India; Cairo, Egypt; and Al Jubail, Saudi Arabia risky from an air pollution perspective. Cleaner air can be found in some cities in Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Alaska, and Hawaii.

What Can We Do about Air Pollution?

Fortunately, air pollution is a modifiable condition that can be reduced by replacing driving with walking, biking, or taking public transportation. For outdoor joggers, exposure to high levels of air pollution does not reduce the benefits of physical activity on both the incidence and the recurrence of heart attacks. Individuals at risk, such as those with heart problems or the elderly, can stay inside when air pollution levels are high. Installing filtration equipment in the home ventilation system can also reduce exposure.

Finally, we need to urge our politicians to develop standards for environmental risk factors such as air pollution and pass laws to protect us from these health risks.

It’s 50 Years of Franklin, Charlie Brown!

He never kicked that football. His baseball team was historically terrible. He got nothing but rocks for Trick-or-Treating. And he was not a noted director of Christmas pageants. Yet Charlie Brown can count one absolute triumph on his resume. Fifty years ago today, Charlie Brown made a friend. That friend, Franklin, broke barriers, infuriated segments of the readership, and remains a radical statement from a tumultuous time. Why? Franklin was the first African-American character in Peanuts.

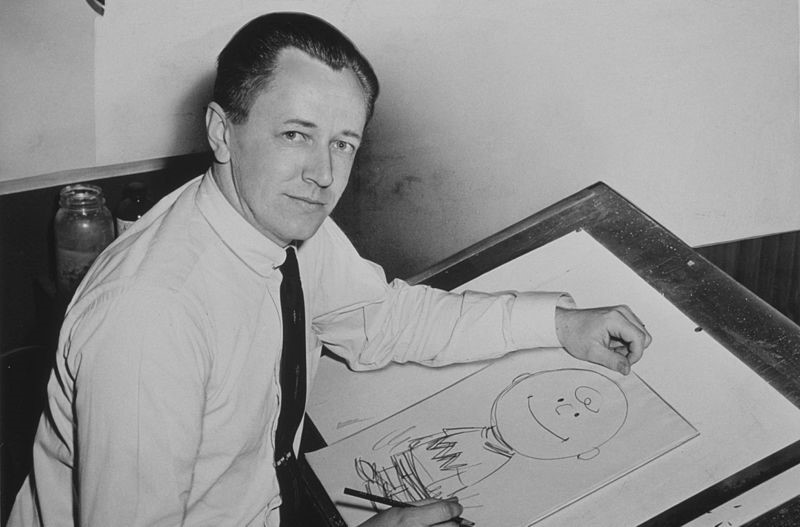

Franklin’s origins began in a series of correspondence between Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz and a school teacher from California named Harriet Glickman in the spring of 1968. Schulz by that time was well established, achieving fame with Peanuts in the years since its launch in 1950; The Saturday Evening Post visited him in 1957, taking a look at the comics’ popularity and merchandising strength. The strip had caught notice not only for its humor and Schulz’s seemingly simple but sophisticated art, but for the creator’s injection of philosophy and social awareness.

Glickman, a mother of three, first wrote Schulz in April of 1968 after considering what positive actions people could take in society following the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. earlier that month. She asked Schulz to consider adding African-American children to the cast, noting herself that it might be a difficult proposition considering the tenor of many institutions, including newspapers, syndication interests, and advertisers. Schulz responded that he and other cartoonists would love to, but was primarily concerned that he might seem “patronizing to our Negro friends.”

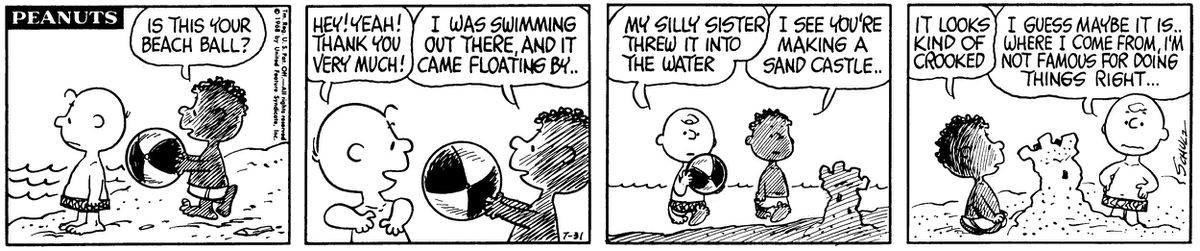

Glickman and Schulz continued to write, with Glickman offering to solicit the opinion of other parents and Schulz weighing his options. By July 1st, he’d written Glickman and told her to keep an eye out for the July 31st strip. That would be the day that Charlie Brown met a new friend on the beach. That friend turned out to be Franklin.

Charlie Brown first meets Franklin while searching for a lost beach ball. Franklin finds it and returns it, and the pair teams up to build a sandcastle. It was simple, sweet, and completely radical. In an interview collected in the book Charles M. Schulz: Conversations, Schulz recalled a “southern editor” who wrote him and said, “I don’t mind you having a black character, but please don’t show them in school together.” Schulz ignored him. In fact, Franklin would later be shown in school, seated in most classroom shots in front of Peppermint Patty.

Schulz recounted some further negative reactions in an interview with Michael Barrier in 1988. Schulz said, “I finally put Franklin in, and there was one strip where Charlie Brown and Franklin had been playing on the beach, and Franklin said, ‘Well, it’s been nice being with you, come on over to my house some time.’ Again, they didn’t like that.” Schulz also recalled a discussion with Larry Rutman, who at the time ran King Features Syndicate (which distributed Peanuts to newspapers). Schulz said, “I remember telling Larry at the time about Franklin—he wanted me to change it, and we talked about it for a long while on the phone, and I finally sighed and said, “Well, Larry, let’s put it this way: Either you print it just the way I draw it or I quit. How’s that?”

Schulz seemed mindful that Franklin would be acting as a sort of representative character. Of all the cast, he’s probably the nicest to Charlie Brown, outside of Linus, and is generally depicted as warm and fair. Schulz seemed to do his best to avoid making the character a stereotype, and even lent him some extra depth and topicality by indicating that Franklin’s father was serving in Vietnam.

Franklin went on to appear regularly in the strip and in media spin-offs. His first animated appearance came in the 1972 movie, Snoopy, Come Home. He would pop up in many specials (notably in A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving in 1973) and subsequent TV series and films; he was among the characters to appear in the most recent big-screen adaptation, The Peanuts Movie, in 2015.

Over time, a number of people would recall the positive impact that Franklin had on them. Chief among them may be Jump Start cartoonist Robb Armstrong. In an interview with Renee Montagne for NPR’s Weekend Edition, Armstrong related that he already wanted to be a cartoonist, and then Franklin appeared, allowing him to see someone that looked like him. Years later, Armstrong would send Schulz a copy of his comic strip featuring a Snoopy gag, and it sparked a friendship between the two. Later, Franklin would be given the last name Armstrong (in animation; his last name never appeared in print) as a tribute to their bond.

It’s true that Franklin lacked some of the defining eccentricities of other cast members, but that didn’t stop his inclusion from being quietly revolutionary. Franklin would inspire people like Armstrong, endure as a character, and gently nudge young readers toward the notion that, as Martin Luther King Jr. famously said, the content of your character is more important than the color of your skin.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Writing It Down Can Help Improve Your Progress

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

As you work on changing your thoughts and “friending” yourself, creating a Thought Log with the ABCDE format will help you analyze events in your life and track progress. You might dedicate a special journal just for this exercise.

- When something upsets you, jot down the activating event (A), dysfunctional beliefs (B), and emotional consequences (C) of your thoughts.

- Consider what thinking category causes you to feel bad (all or nothing thinking, emotional reasoning, etc.).

- Now you can dispute (D) the thought and replace it with a kinder, factual, probable, and useful perspective.

- Finally, you can evaluate (E) how strongly you felt the initial emotion. Perhaps in the beginning you felt frustrated at an intensity of 90 on a scale of 1 to 100.

- Record the new rating of frustration (1 to 100) after you begin thinking differently.

You may not like keeping a journal with this much structure, and that’s okay. But I do recommend you take time to evaluate how this information affects your life.

Sit down with paper and pen, or at your computer, and write about which fallacies of thought have kept you from losing weight and sustaining that weight loss. You don’t need to write a novel. Don’t worry about spelling or grammar and feel free to use bullet points instead of sentences.

I suggest you start with writing how the environment and your thinking influenced you to regain weight in the past. Suppose you gained weight after a combination of events — you hurt your foot in October, followed by the stress and social events of the holidays, and then you felt discouraged and gave up. What if you changed your interpretation of those events — your thoughts and beliefs? Would the story have a different ending?

Write about how you could have changed the environment to ensure better success. Then try writing how you could change your thoughts if you couldn’t change the environment. How could this situation end with a better outcome? While you’re at it, write about several of those possible good outcomes. This will show you how changing your thoughts could lead to much better results.

This writing exercise will be like a dress rehearsal for similar challenges in the future. Instead of falling into the same traps as before, you’ve prepared yourself to respond in a healthier way. As with anything you practice the right way, you’ll soon develop thinking skills and new confidence to overcome future challenges to maintaining a healthy weight.

Let’s End the Civil War

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

—This account appeared in the August 11, 1962, issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

There were more Confederate flags sold during the first year of the Civil War Centennial (1961) than were sold throughout the South during the war itself (1861-1865). One hesitates to estimate the number of Confederate flags that will be sold during the next three years, but the prospects are that the total will be more than all the flags sold in all the wars the nation has fought.

Yet the Civil War Centennial is hardly a promotion dreamed up by flag manufacturers. Nor is the centennial merely a project of the enthusiastic city booster to lure the tourist dollar to his hometown. No city booster anywhere in the south or in the north has any intention of proposing a celebration of other conflicts like World War I or World War II or the Korean War.

We celebrate no other war because essentially we believe those wars are over, their outcomes final, the course of history decided. But there are centennial committees throughout the south which would have us think the Civil War is not completely done with, that it ought to be refought. These fellows grow beards, wave flags, and charge over the few meadows the housing developers have left — hoping somehow by this exertion to sustain the illusion that the South may yet snatch victory from defeat. They do everything to re-create the Old South except save Confederate money.

The war started again in July 1961 with the grand reenactment of the Battle of First Manassas (Bull Run), which the South, not surprisingly, won again. Twenty-three states on both sides sent participants, although a large number of soldiers came from the ranks of the North-South Skirmish Association, an organization founded in 1950 by devotees of the muzzle-loading rifle, whose purpose is to hold shooting contests from time to time. For the First Manassas reenactments the participants wore authentic uniforms and carried old muskets whose blank cartridges often bruised the shoulder, blacked the face, and seared the eyes of the unwary.

The son of a friend of mine, a “corporal” in the Guilford Greys (Greensboro, North Carolina), has been “killed” three times since First Manassas and is perfectly willing to give his life in a fourth reenacted battle. It is nice , indeed, to have more than one life to give to one’s country, although the plane fare to the different battlefields is considerable.

The centennial engenders nothing if not sacrifice. The late Bill Polk, editor of the Greensboro Daily News, once showed me a letter from a North Carolina high-school boy which read, in part: “I wish I had been born before the Civil War and had died at Gettysburg.” These mock recruits, I suspect, secretly hope one day the batteries will load real projectiles in the cannons, and the bayonets will be cold steel, not rubber. And this time they will take Washington, D.C.

On To Washington! On To Yesterday!

Certain centennialists seem to believe that once they take the capital, they can force upon the Supreme Court the decisions that will restore the old plantations, the crinolines, the dueling pistols, the house on the hill with smoke coming out the chimney at twilight, and little Sambo rolling in laughter under the magnolia. Ah, what a glorious dream!

Yet it is not entirely an idle dream. The Civil War centennialists have some vague idea that, if they can mount a sufficient show of force, they may not have to deal with the more aggravating and immediate problems of Southern life — the problems that press upon an urban, industrial area that is leaving behind the old, easy agrarian values.

Thus the centennial has turned into a party rather than a pageant. I have even seen a few automobiles decorated with the Stars and Bars, filled with black students, each of the occupants therein wearing the butternut-gray dinks of Confederate soldiers. No centennial committeeman, no matter how skillfully he ties his bowstring, is completely unaware of what is going on in the business district of his hometown. He doesn’t even have to work behind a store counter to know that, in the states of the old Confederacy, at least one-third of all the purchasing power and one-half of all the credit buying comes from the pockets of grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the black slaves.

That realization is why the centennial is something less than a huge success in the big Southern cities. The plan for my own home, Charlotte, North Carolina, by far the largest city of the two Carolinas, was to commemorate the fact that it was the site of the Confederate Navy Yard. It seems that, after the war broke out, the naval stores at Portsmouth, Virginia, were seized and transported inland to Charlotte. The long boardwalk is still called “the wharf.” But except for the members of the committee itself, few people are even aware of the centennial, let alone a Confederate Navy Yard.

Was the “Old South” A Myth?

The chamber-of-commerce fellows are selling the ideals of the modern industrial world because the ideals of the Old South were only make-believe currency. There were Southerners before 1800, but there was no “Old South.” One of our Southern writers, Wilbur J. Cash, in his book The Mind of the South, recalled that boys who cleared out the Indians in the Carolina backwoods lived to command brigades at Bull Run, which means that the Old South could not have been more than two generations old.

The fact is that the Old South was nothing more than a myth and a poem and, as Jimmy Street, another Southern writer, put it, a malady for which there fortunately is a vaccine — the industrial payroll.

The Civil War started with the Negro in slave cabins. But all of the blanks and muskets and beards will not disguise the truth that Negroes serve today on the Republican and Democratic national committees. The real Confederates found cover behind occasional tar-paper shacks. In their place today, the re-created regiments and brigades have to charge around factories where the skilled workmen inside knock off a few minutes to cheer them on.

The time has come to end the Civil War because we are one country with one economy. We cannot take time out from industrial and urban problems of unemployment, housing, schooling, and civil rights to indulge ourselves in silly excess, celebrating a time that no longer is — and never was. The truth is that, at best, the centennial provides but a minor amusement.

“Lets End the Civil War,” August 11, 1962

When Freedom of Speech Hit an All-Time Low

First-amendment rights hit an all-time low between 1917 and 1919.

As the federal government raced to unite the country behind the war effort, it cracked down on any opposition or criticism. Congress passed the Espionage Act, which prohibited any action that would disrupt the country’s military or aid the enemy. Then it passed the Sedition Act, which outlawed any speech or writing that put the government’s war program in a negative light.

Over the next few years, more than 2,000 people would be charged with violating the new limits on free speech. One of the most famous of these was Eugene V. Debs, a union organizer and socialist.

In 1893, Debs had been president of the American Railway Union when it went on strike after the Pullman Company, maker of railway cars, cut its workers’ wages by 28%. Union members refused to handle Pullman cars or any cars attached to them. The federal government issued an injunction requiring striking workers back on the job, but Debs refused to comply. Ultimately the army was sent in to break the strike. Thirty strikers were killed and Debs was imprisoned for 30 days.

While in prison, Debs came to believe he could do more good as a socialist than a union administrator. Starting in 1900, he campaigned as the socialist candidate in five presidential elections. He never came close to winning, but he raised awareness of the disparity between rich and poor in America and earned some grudging respect from his opponents (as seen in this Post profile from 1908.)

On June 16, 1918, Debs had delivered a speech in Canton, Ohio, that caused him to be arrested and convicted under the Espionage Act. Debs appealed to the Supreme Court, but the court upheld his conviction. It believed Debs was guilty not for what he said in his Canton speech but because of a document he had previously written, “Anti-War Proclamation and Program,” as well as other comments. These showed Debs’ intention was to disrupt military preparations.

A long-time pacifist, Debs had been aware of the Espionage Act and had toned down his speech to avoid making statements that directly opposed the war effort. But Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, who wrote the court’s unanimous opinion, noted that Debs had previously said things like “the master class has always declared the war and the subject class has always fought the battles… the subject class has had nothing to gain and all to lose, including their lives; that the working class, who furnish the corpses, have never yet had a voice in declaring war and never yet had a voice in declaring peace.”

At this point in his career, Holmes had little tolerance for opposition to the government. He believed Debs represented a serious threat to democratic government and the rights of property. And urging others to disrupt the draft was no different from disrupting it themselves. He believed speech, as much as action, had the power to disrupt public order. It was in this opinion that Holmes gave his famous analogy of unfettered speech: “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man shouting fire in a theater and causing panic.”

Justifying the right to abridge the first amendment, Holmes wrote that a statement fell outside of free-speech protection if there was “a clear and present danger” it would bring about a harm that Congress has the right to prevent.

On April 13, 1919, Eugene Debs began his ten-year prison sentence. Far from being a lone, angry radical, he entered the federal prison in Oregon a sympathetic figure, jailed for objecting to a war that was now five months in the past.

In 1920, he announced his fifth run for the U.S. presidency from his jail cell and that November managed to win nearly a million votes.

Had Debs’ trial come before the Supreme Court after 1918, Justice Holmes might have argued for his acquittal. In the months following his Debs decision, he had changed his mind about the limits of free speech. He presented his ideas in his opinion on Abrams v. U.S. The case involved Russian sympathizers who urged workers to impede the manufacture of weapons for the American troops stationed in Russia. The Court upheld the Espionage Act, but Holmes dissented.

This case didn’t involve a clear a present danger, Holmes wrote. America was not officially at war. Moreover, a conviction required proof of specific intent to commit a crime — a reversal of his interpretation of Debs’ intentions.

Holmes went even further, claiming that Abrams’ ten-year sentence followed by deportation indicated he was being prosecuted not for his speech but for his beliefs.

It was here that Holmes recorded another of his memorable concepts. Free speech was essential and should be protected, he wrote, because the “marketplace of ideas” produces better thinking. Good ideas will challenge, and overturn more limited concept. Free speech leads us toward the truth.

Debs’ health began to fail in prison. In 1921, President Harding extended clemency to Debs, but did not issue a pardon. The administration still regarded him as dangerous. In a White House statement, Debs was described as “a man of much personal charm and impressive personality, which qualifications make him a dangerous man calculated to mislead the unthinking and affording excuse for those with criminal intent.”

Yet Debs was personally invited to the White House the day after his release from jail. He was greeted cordially by President Harding, who said, “Well, I’ve heard so damned much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am now glad to meet you personally.”

Though Holmes distanced himself from the “clear and present danger” doctrine, the Supreme Court used it as a precedent until 1969. In that year, the court raised its protection of free speech in its Brandenburg v. Ohio decision. The government, it ruled, can only limit speech intending to produce “imminent lawless action.”

Featured image: Debs and Hanford campaign poster from 1904 (Socialist Party of America)

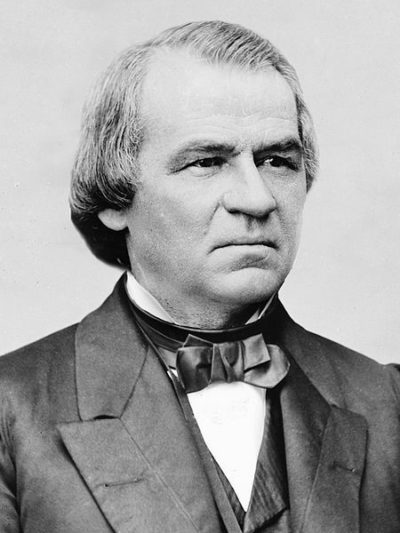

The 14th Amendment Settled, and Started, Citizenship Battles 150 Years Ago

Amending the United States Constitution remains a monumental act, even if such modifications were always intended from the moment that the document was designed. While every amendment has faced challenge and debate, few groups have inspired as much controversy and litigation as the so-called Reconstruction Amendments. Amendments 13, 14, and 15 came in the aftermath of the Civil War, and their implications and legacy have reached further than many expected. The ratification of the 14th Amendment, covering citizenship, due process and much more, and its certification were proclaimed by Secretary of State William H. Seward 150 years ago on July 28th.

The birth of the 14th Amendment came out of a complicated dance of conflicting political priorities. The sudden influx of “new” citizens created by the 13th Amendment (which ended slavery) threatened to upend the power balance in the south in the House of Representatives because a larger population requires more representatives. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 passed Congress, guaranteeing citizenship to every person born in the United States regardless of race, color or “prior condition of servitude.” Andrew Johnson would veto the bill twice, but Congress overrode him, turning it into law. However, not everyone in Congress was satisfied that this solution should lie outside the Constitution.

More than 70 proposals for a new amendment to address citizenship were written. Ultimately, after much debate and a number of counter-proposals, modifications, and compromises, the text of the 14th Amendment was codified and passed. Many in Congress were disappointed that the bill didn’t go so far as to address voting rights for former slaves; fortunately, that would be covered less than two years later with the ratification of the 15th Amendment.

The Amendment contains five sections, and they cover an incredible amount of legal ground. Section 1 covers birthright citizenship, the right to due process, and equal protection for citizens under the law. Section 2 acknowledges that everyone (well, males at any rate) was a “whole person” rather than the three-fifths allotted to black Americans previously; it also establishes some voting protections. The third section works to prevent previous rebels (see: military and elected officials of the Confederacy) from holding office, military rank, or civil service jobs unless they would receive a 2/3 vote of Congress giving them approval. Section 4 more or less tells the South that they’re stuck with their debts in the wake of the war; if they accrued debt from borrowing to fund the unsuccessful rebellion or losses from having their slaves freed, that was, legally speaking, too bad. The final section simply affirms the authority of Congress to enforce the Amendment with legislation.

Since its ratification, the Amendment has figured into elements of at least 90 Supreme Court cases, due in part to the large ground in covers. Some of the cases rank among the most important in U.S. history. The Amendment played a part in the school segregation breakthrough of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 due to the Equal Protection clause; that same clause was involved in the election-deciding Bush v. Gore in 2000. Issues of Substantive Due Process were raised by Roe v. Wade in 1973 when the court ruled in part that the right to privacy included a woman’s decision to have an abortion. Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015 also invoked both Substantive Due Process and Equal Protection on the way to a decision that legalized same-sex marriage.

Today, the issues surrounding the 14th Amendment continue to fuel considerable public and legal debate. As recently as July 19th, Johns Hopkins University historian and author of Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America Martha S. Jones spoke to The New York Times on how the protections of the Amendment figure into the current controversy surrounding immigration. In response to a question about whether or not the lessons of history can solve current problems, Jones says, “I don’t think history is a blueprint. It can’t be. There’s too much that’s particular to our own time and place. But I do think the debate about birthright citizenship is here, and you can’t be well equipped for it unless you are familiar with where it begins.”

News of the Week: Summer Vacation, Comic-Con, and How to Get Free Fries for the Rest of the Year

Dog Days

While the annoying commercials tell me at least 20 times a day that “it’s gonna be a Subaru summer” — I swear one of them just came on as I was typing that sentence — it’s also time to buy school supplies again.

That’s right, kids: Only three weeks after the Fourth of July and you already have to start thinking about math and social studies (is that still a thing?). I’ve started to see back-to-school commercials and store advertisements already. It seems rather cruel to expose kids to these things when it’s still 89 degrees and they’re in shorts. Can’t they at least wait until August to run these things? We’re still in the dog days of summer!

I always thought that the dog days of summer referred only to the month of August, but it’s actually a period that runs from July 3 until August 11. I also always thought it had to do with dogs not liking the summer heat, spending the day laying around the house panting and sleeping. But it actually has to do with Sirius, “the Dog Star,” which rises during the above dates.

But don’t worry, kids, there’s still plenty of vacation time left. Don’t let anyone tell you different. You can go to the beach and to the movies and to the mall and to your jobs to make spending money. Wait until mid- or late August to make your Staples run for notebooks and pens and anything else you’ll need for the new school year. You need to just listen to the car company. It’s gonna be a Subaru summer, and you might as well enjoy it while it lasts.

SHAZAM!

I won’t go into detail about what happened at the Comic-Con convention in San Diego, where fans gather to celebrate their favorite sci-fi/superhero/fantasy films and TV shows — io9 has a good summary of the good and the bad at this year’s show — but I do want to post one trailer that made its debut.

SHAZAM! (and yes, it has to be written all in caps and with an exclamation point) looks like it could be fun. It’s based on the DC comics character — he was also known as Captain Marvel — and it stars Chuck’s Zachary Levi. It looks like a mix of a superhero movie and the Tom Hanks movie Big.

Here’s the Story, of a House for Sale

I never missed The Brady Bunch when I was a kid — it was a Friday night staple, along with The Partridge Family — so I’d like to buy the house used as the exterior on the show. Unfortunately, I don’t have $1.8 million.

But if you have that much and need a second home (and you’re a fan of classic television), you can now buy it. It’s in North Hollywood, California, and looks quite different than it looked in 1970.

The inside, of course, looks nothing like it did on the TV show. Unlike the Brady house, the bathrooms have toilets.

Why Didn’t Somebody Tell Me There Was a New Philip Marlowe Novel?

Raymond Chandler is one of my favorite writers, so I get a little antsy when someone writes a novel based on his most famous character, detective Philip Marlowe. But I’ve been pretty happy with the Marlowe novels written by others, whether it was Robert B. Parker’s Poodle Springs or Benjamin Black’s The Black-Eyed Blonde. They’re not exactly Chandler, but they’re good facsimiles.

I didn’t realize that there was a new Marlowe book released recently. It’s titled Only to Sleep, and it was written by Lawrence Osborne. And here’s a twist: It’s set in 1988 and features an older, retired Marlowe.

Though Chandler once complained to his agent that “slick” magazines like the Post would never publish him, he actually did have a story published in our pages. It’s called “I’ll Be Waiting,” and it appeared in the October 1939 issue.

Free French Fries? There’s an App for That

National French Fries Day was a couple weeks ago, but even if you missed it, you still have time to celebrate. McDonald’s is giving away free medium fries every Friday for the rest of the year! You have to make at least a $1 purchase and download their app, but that’s a pretty good deal.

It might be one of the last times you order from an actual human being at McDonald’s. By 2020, the company wants to put self-ordering kiosks in all of their U.S. restaurants.

RIP Adrian Cronauer, Shinobu Hashimoto, Jonathan Gold, Anne Olivier Bell, Elmarie Wendel, and Gary Beach

Adrian Cronauer was the real-life disc jockey played by Robin Williams in the movie Good Morning, Vietnam. He died last week at the age of 79.

Shinobu Hashimoto wrote several screenplays, including the classic Akira Kurosawa films Rashomon and The Seven Samurai. He died last week at the age of 100.

Jonathan Gold was the longtime food critic for the Los Angeles Times. The Pulitzer Prize winner died Saturday at the age of 57.

Anne Olivier Bell not only edited the diaries of Virginia Wolff, she was one of the members of the Monuments Men, the group that got together to find and protect stolen artwork during World War II. (The story was made into a 2014 George Clooney film.) She died last week at the age of 102.

Elmarie Wendel was best known as landlady Mrs. Dubcek on 3rd Rock from the Sun. She also had roles on The George Lopez Show, NYPD Blue, and many other shows. She died last week at the age of 89.

Gary Beach won a Tony for his role in the Broadway musical The Producers. He also had roles in Beauty and the Beast, La Cage aux Folles, and many TV shows. He died last week at the age of 70.

This Week in History

Ernest Hemingway Born (July 21, 1899)

It may be hard to believe, but the Post rejected all of the stories the writer submitted. But we did publish a story from his grandson John.

Debut of Bugs Bunny (July 24, 1940)

While a Bugs Bunny-ish character made an appearance in Porky’s Hare Hunt, he made his official debut in the Warner Brothers/Merrie Melodies animated short A Wild Hare.

http://www.dailymotion.com/embed/video/x4053d

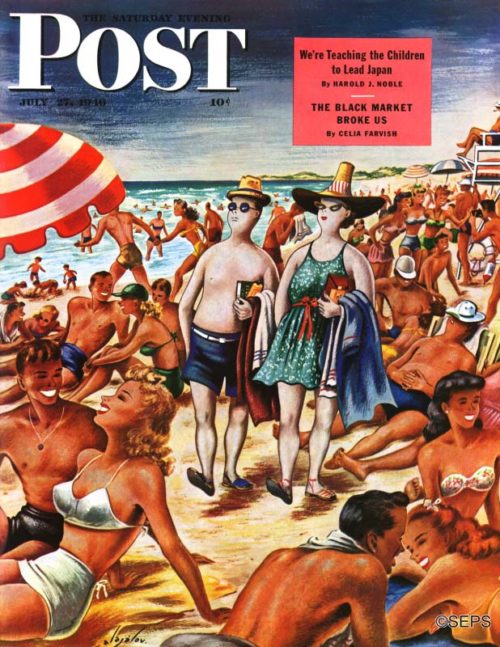

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Palefaces at the Beach (July 27, 1946)

Constantin Alajalov

July 27, 1946

I wonder if today this Constantin Alajálov cover would have to have a different title?

Sunday Is National Cheese Sacrifice Purchase Day

I talk about many different kinds of food holidays here, and I always thought the oddest-sounding holiday I’ve come across was National Sneak Some Zucchini onto Your Neighbor’s Porch Day. But now I think we have a new contender in that category: National Cheese Sacrifice Purchase Day.

No, it’s not some bizarre ritual where you sacrifice cheese to some god. It actually has to do with getting rid of mice in your home by sacrificing some cheese to a mousetrap. I’ve had mice, and I find that peanut butter actually works a lot better.

Come to think of it, Sneak Some Zucchini onto Your Neighbor’s Porch Day is still the oddest food holiday.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

National Day of the Cowboy (July 28)

This is the 14th annual celebration of cowboy culture and pioneer heritage.

International Beer Day (August 3)

If you celebrate the day a little too much, please note that August 4 is International Hangover Day.

Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott: Don’t Miss Mission Impossible and Sorry to Bother You

Is the new Mission Impossible film the greatest action movie ever made? Bill Newcott talks about Tom Cruise’s latest. He also takes a look at Sorry to Bother You, the hilarious, thoughtful, and totally whacked out comedy that picks up where Get Out left off. Bill also reviews the latest home movie releases: Ready Player One, Final Portrait, and A Matter of Life and Death.

Leaves

Every Sunday, Jason and his parents, Scott and Shirley, have steak dinner. The vegetable sidekicks change, but the main performer is always the iron-filled, bloody chunk of filet.

This particular Sunday came with a chill lingering in the air. Whenever Keith was invited to steak dinner, this chill came with him — a tension-lathered gaze steaming from Scott’s eyes, like a fire on the horizon when a sunset was expected.

Scott’s normal Sunday was a grunt here, a mumble there, minimal eye contact, and this night, Shirley and Keith were exceptionally chatty.

Over the years, Scott has tried to see Keith like Shirley and Jason do, but efforts passed unsuccessfully. To Scott, Keith is invisible. To Jason, Keith is his best friend, his forever sidekick. To Shirley, Keith is the love she’s never had before.

“God, that is so ingenious, Keith. Where did you come up with that?” Shirley says.

Scott doesn’t listen. Grunt. Mumble. Repeat.

“Did you hear that, Scott?” Shirley turns to Scott.

“No. No. I didn’t,” Scott returns. He can’t hear him, either. Scott believes that Jason made up Keith when he was four years old, and he thinks that Shirley, with the good heart she hordes, simply cannot admit to Jason that she, too, doesn’t see Keith.

Jason chimes in, “He was talking about dreams.”

Scott shoves an entire radish in his mouth. “Yeah? What about ’em?”

Shirley continues, putting her hand on Keith’s hand while she vocalizes his words. Of course, to Scott, Shirley is putting her hand on a napkin next to an empty plate. “He said he thinks dreams are part of the human subconscious, or,” She looks up at Jason. “I’m going to butcher it. It was so beautiful. What did he say?”

Jason finishes for her. “He said that the human subconscious, or figments of our subconscious, like dreams — that they’re another world where other humans live. That humans enter another human’s dream when they die. That none of it was really real, but it felt so real. That our life is a dream, even if it feels like a nightmare sometimes.”

“Oh, that was it. So interesting,” Shirley says.

“Sounds dumb to me.” Scott huffs.

Naturally, they all collectively feel awkward, looking down at their plates as if they were trying to tell them something. Scott guzzles his Scotch.

Shirley defensively comes to Keith’s aid. “I thought it was pretty.”

Scott grunts. Mumbles. Repeats. Adds in another guzzle.

Scott picks up his knife, looks at Jason, and stabs his filet. Blood spatters up to his cheek and trickles down towards his lips. Scott sticks his tongue out of his mouth and slurps the blood off his cheek.

Shirley’s cheeks look like someone took the beets off her plate and rammed them repeatedly on her face, leaving a permanent mark. Shirley has maintained a PTA middle-aged mom haircut for nearly all of her marriage to Scott. Shirley didn’t care for the way it shaped her face, but it was the one thing she seemed to know for certain that Scott liked about her, so she kept it. The new blond highlights she collected went unnoticed by Scott, but she thought it made her look younger.

She could tell that this moment was the time to sit Scott down and have the tough conversation. Every time Shirley attempted this controversy in the past, Scott didn’t truly hear her. That was clear.

“Scott,” Shirley says, “Can we talk a minute?” She hesitates, per usual.

“Jason, go upstairs,” Scott says, barely looking up to acknowledge Jason’s presence.

Jason goes upstairs. “C’mon, Keith,” he says as they run up the stairs.

Shirley has a nervous twitch that she has perfected around Scott. She twiddles her thumb and first fingers of each hand, making an infinity symbol. “We should talk about this Keith situation.”

“He’s crazy,” Scott says.

She can’t find her voice for a few moments but squeezes it out of her vocal chords like a bulbous item out of a vacuum cleaner, temporarily clogging it. “He’s … not …crazy. He’s just young. Keith is…” She unravels her words like an old-time scroll being read to someone unimportant.

“This isn’t about Keith. This is about Jason. He’s crazy. He thinks Keith is sitting right in front of us, having dinner. We have to buy the imaginary kid a steak, Shirley.”

“You … you still don’t see him?” She finger-infinities again. Shirley has come to recognize Scott’s hostility towards Keith — and Scott’s subsequent perception that Jason is crazy — as repression. Scott doesn’t want to see Keith, so he doesn’t.

“No. And you don’t either. But Jason does. This is a problem, Shirley. You need to cut the act. Doing this little performance with Jason, acting like you see Keith, too, it’s only enabling him — making it worse. We need to take him to be evaluated again.” He speaks with conviction. “We should do it tonight. We can’t wait any longer. He’s going to grow up to be a serial killer. And you’re not helping.”

“It’s too late for the doctor’s.” Her voice trickles out like a waterfall in the distance of a Costa Rican village.

“Jason!” Scott screams.

“Don’t get mad at him,” Shirley mumbles.

Jason descends from the staircase. With Keith. “What’s up, Dad? Keith and I were just about to watch Die Hard.”

“Jason, you’re not going to school tomorrow. We’re going to take a little field trip.”

“Scott — he has to go to school.”

“Keith and I have a biology test tomorrow.”

“I’ll write you a note. It’s final. Be up at eight.”

Jason gets up at eight o’clock for his mysterious field trip. Except, due to experience, Jason knows the plan. Like clockwork, every few months, Scott has this same fit.

His dad is positioned at the kitchen table with eggs and coffee in front of him. Another plate mirror-images his meal across from Scott.

“Sit. Eat. Eggs are brain food. Coffee to wake you up.” Scott’s forehead gains wrinkles daily. His constant downward concocting of his head made his double-chin pronounced. His furrowed-brow made frequent appearances in pictures on the Georges’ mantel over the fireplace.

There is one picture hanging on the wall near the staircase where Scott looks happy. He’s young. He has a single-chin. His wrinkles on his forehead were in hiding then. It was autumn in Alaska. Jason, who was four at the time, is wrapping one arm around Scott’s head, and Shirley stands above them. Leaves drown out the light blue sky in the background. Scott’s eyes match the color of the leaves, and there’s something about the crisp autumn air that is visible in the picture.

“Thanks.” Jason sits down. “What’s Keith going to eat?”

“Keith’s staying home today. Got it?”

Jason turns to the staircase, in which Keith’s elbow is wrapped around the wooden hand rail. “Sorry, Keith.”

Jason walks out of the evaluation room, smiling, as is the doctor. Scott sits in the most isolated chair of the waiting room, ticking his big toes noticeably in his shoes. When he sees Jason exiting the “Are You Crazy?” room, he shoots up as if he sat on a trampoline.

“How’d it go?” he asks the doctor. Jason lingers with them, and Scott pulls the doctor into the room, telling Jason to wait outside. He closes the door.

“My evaluation of Jason is the same as Doctor Mulnay’s preliminary findings. Jason is mentally healthy and right on track.”

“You’re pulling my leg.” Scott laughs as if he has heard that joke about the fungus walking into a bar that makes him chuckle every time.

The doctor repositions the envelope in his hands. “Based on my discussion with Jason, he simply requires more attention—”

Scott cuts the doctor off. “So you’re saying that he’s imagining someone, because I don’t pay enough attention to him. Perfect. The problem is me.”

“No, Mr. George. It is not your fault. Jason is psychologically healthy, and that should be cause for celebration. Excuse me, I have another appointment in a few minutes.” The doctor positions his hands toward the door, opening it and allowing Scott to exit in front of him.

“Jason!” Scott yells. “Let’s go.”

Shirley is home from work when Scott drops Jason off. She sees the headlights in the driveway and watches as Scott backs up and speeds down the street.

“Nice of your father to come in and say hi to me before rushing off,” she says sarcastically.

“Keith wants to know how your big meeting went,” Jason says in return.

She looks at Keith as she answers. “How nice of him to remember. It was stressful. My heart was,” she put her hand on her heart to show a thumping movement. “But, I knew the material, and that showed, so I think it went well.” She turns to Jason. “How’d the…?” She doesn’t finish her question, rather she moves her wrist in a circular motion toward the door.

Jason knew what she meant. “Doc cleared me … again.”

“You know your father … he tries to be thorough.” She moves to the kitchen, knocking on cabinets, dissecting pots and pans from their homes, getting dinner ready.

“He’s the crazy one,” Jason mumbles under his breath.

Keith shakes his head. “It’s not his fault, dude.”

“Jason!” Shirley yells from the kitchen. “Do you and Keith want to play basketball while dinner’s in the oven?”

Scott gets home from work, disgruntled, parking his car on the street while Keith, Shirley, and Jason play basketball.

“Who’s winning?” He asks, trying his best to engage. To Scott, the only ball in sight is the one in Shirley’s hand.

“Keith,” Jason answers.

Scott grunts, sarcastically shaking his head. He starts walking into the house but turns back. “Where is Keith?” he asks.

“Taking a shot at the foul line…” Shirley says. “You should have heard him a minute ago. He was talking about concrete.”

“Concrete, huh?” Scott says. “Sounds invigorating.”

“No, it was really rad, Dad.” He turns to his mother. “Rad, Dad. It rhymes.”

Scott snorts out a laugh as if he is trying to imitate how loud someone was snoring in a bed next to him at a European hostel. “Funny,” he says.

“Anyway, Dad,” Jason calls out to him as Scott tries walking in the house through the garage. He stops. “Don’t you want to hear what Keith said?”

Scott pulls in his lips, clenching his jaw overtop of his closed-mouth. He nods his head up and down.

“Well I asked him for advice about Marley.”

“She’s still seeing you?” Scott asks.

“She is, but I kind of messed up. I don’t need to share all the details, but I made a mistake. And I asked Keith for advice, and he — Keith has this way of relating everything to something else, ya know, like he said that nothing is concrete. Even actual concrete, he said, has a period of time when you can still jump into the molding and leave your imprint.”

Shirley slightly bobbed her head, as if she was listening to The Who’s “Behind Blue Eyes.” “It’s a really great perspective, Keith.” She looks directly at the foul line, where Keith stands holding the basketball. Even though it is night, the Alaskan sky carries light blue trickles of the day with it. Keith’s blue eyes match the cold air — the visibility into his aura through his pupils more powerfully clear and beautiful, to Shirley, than the Northern Lights ever could be.

“I don’t get it,” Scott mutters. Angry and uncomfortable at his wife’s ogling an empty space, Scott turns his body towards the garage door. He opens the door, enters it, and pauses in the house to hear the slam.

Jason sits outside on the porch, seemingly rather upset.

Scott parks on the street, a rusty, dark-blue Giant cruiser bike sprawled out like Bambi on the path to the garage.

“You look sad,” Scott says, walking behind him, rumbling his keys.

“No!” Jason shoots up. “Dad. You can’t go in there.”

He turns around. “Why not?”

“Mom. She’s not feeling good. She’s sick.”

“She was fine this morning,” he says, positioning his key in the lock.

Jason takes the key out of the lock and walks to the front lawn.

“Jason. Come back here with my keys. Now.” Scott is pissed.

“You can’t go in, Dad.”

“Tell me the real reason why, right now.”

Jason hesitates. “She has a surprise for your birthday.” He spits it out like too-chewed gum. “Just give her a little more time, please.” His dad’s pinkish, heated face subsides to his skin’s natural color.

“A surprise for my birthday?” Scott smiles for what seems to Jason like the first time in years. For a fleeting moment, he looks to Jason like the picture on the wall. It’s like 10 years were shaved off in just seconds.

Scott thinks of how they haven’t celebrated his birthday with a party in over a decade. After minutes float into half an hour and darkness engulfs the night, Scott breaks their silence. “Can you go check on her? I have to pee. And it’s freezing out here. I left my good coat at home this morning, thinking I’d have access to a heated house after work.”

Jason gets up and uses the confiscated keys in his pocket. Moments later, he walks back out. “They need a few more minutes. They’re almost finished.”

“They?” Scott asks.

“Oh … a party planner … friend. There’s no car here, because … they live down the street.”

“Oh … is that who’s bike is in the driveway?” Scott asks.

Jason and Scott sit on the porch, close enough that their knees’ body heat is almost felt by the other. “Have you ever thought that maybe life is hell or heaven?”

“What?” Jason asks.

“I was thinking about that today for some reason. I think I heard it somewhere. Or maybe I made it up. What do you think?”

“I think I’ve heard it before, too.” Jason tries to think about movies they’ve watched together recently, and then he remembers that they haven’t sat down to a movie since his childhood. “Where’d we hear that?”

“I don’t know. Wherever it was, it’s genius. Sometimes…” Scott looks up, remembering his audience. “Well, sometimes, it feels like life is a test. That’s all.”

“I know what you mean.” Jason thinks of his psych evaluations. He stands up, looking down at his father.

Scott jolts his head upward to Jason who looks at Scott’s graying hairs on the top of his head. He looks at his eyebrows that are furrowing in a commiserating way, instead of their normal disdainful way.

The porch window reflects Jason’s similarities to his dad — their slightly curly hair, only at the ends; their oval egg-shaped eyes; the barely noticeable curvature of their nose; and their lopsided ear lobes. Jason stares at himself in the window for a few elongated seconds. He shifts his feet away from Scott, still facing him, leaning against the railing of the staircase. They stare in each other’s irises until Scott looks down at his hands. “Son…”

“I’m gonna go check on Mom.”

Jason enters the house, locking the door behind him.

“Mom!” he yells.

He hears movement upstairs. Shirley comes down, pulling her robe tied. Her hair looks disheveled, like she used Bed Head Hairspray.

Keith runs passed him, “Later, dude.”

“Wait.” Jason stops him. “Use the back door. My dad’s on the front porch.”

“Your dad’s here?” Shirley asks. Keith kisses the side of her head. They wave silently as Keith walks out of the back.

“Mom?”

“Yeah?” she asks, her cheeks reddening.

“We have to throw Dad a surprise party for his birthday.”

They stand in their positions in the house as if their shoes are glued, silent, their breathing audible.

They take turns looking at Scott’s smiling picture on the wall — both of their faces pure and joyous. They were a family in that moment. The leaves were falling, and they were a family.

“Isn’t that the day we met Keith?” Jason asks.

“Yeah, he was in the park, playing in the leaves.” Shirley approaches the photograph, standing on the second stair. She touches the picture as if the leaves had texture. “That’s his shoe.”

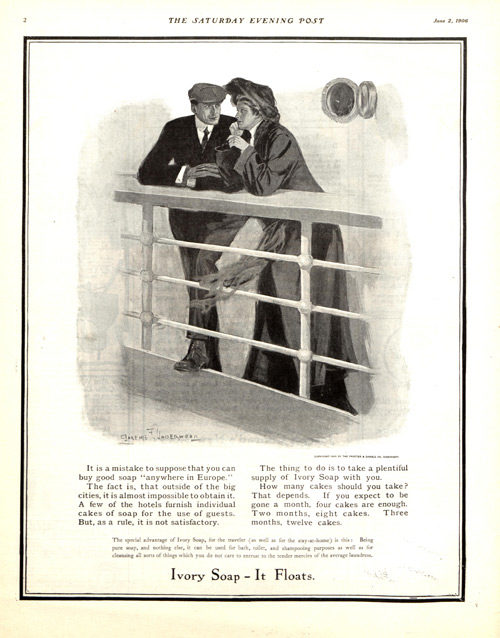

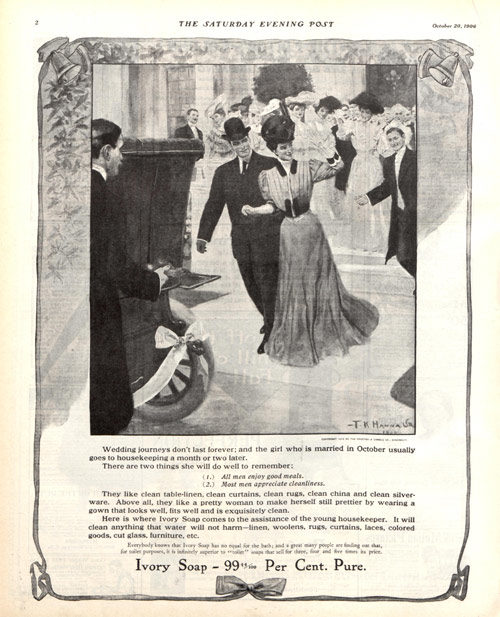

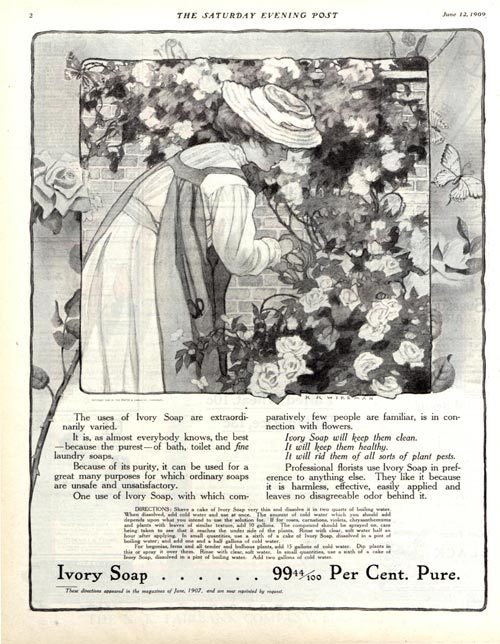

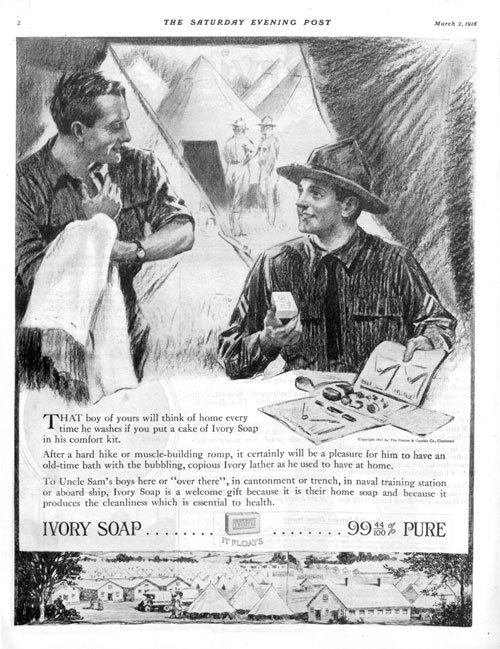

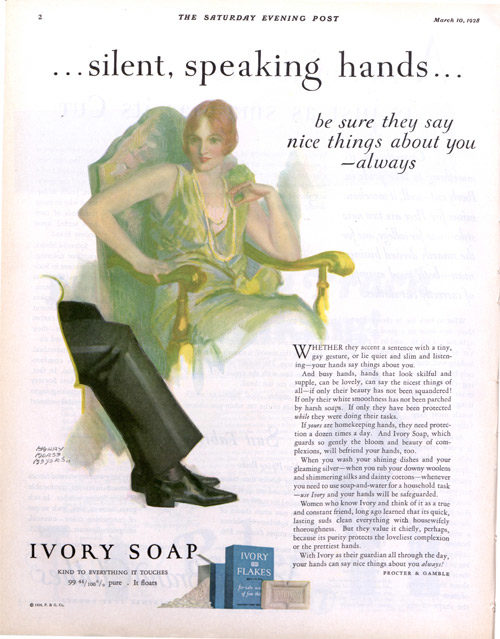

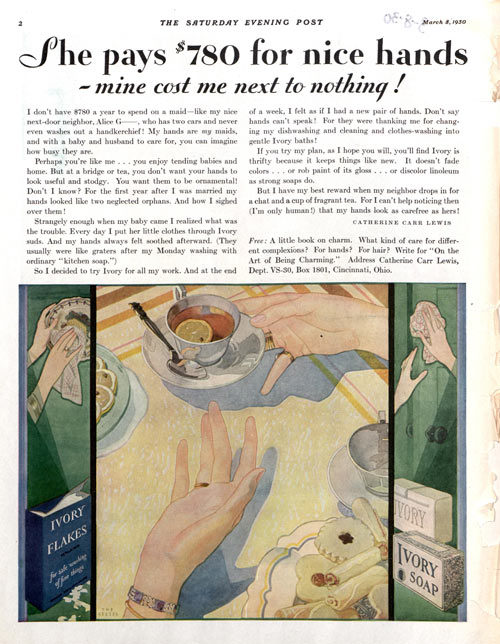

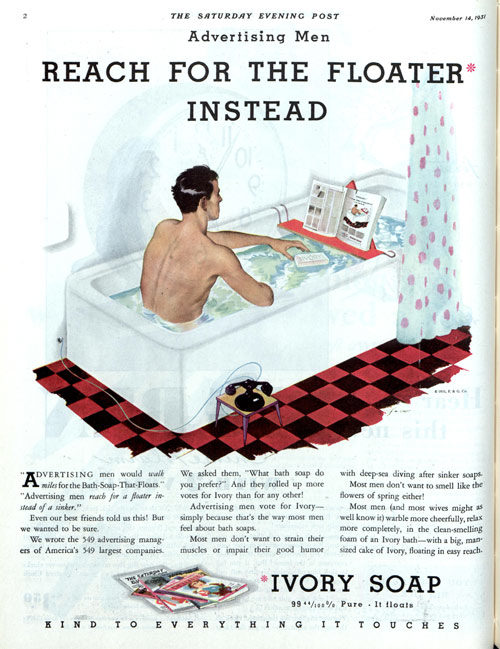

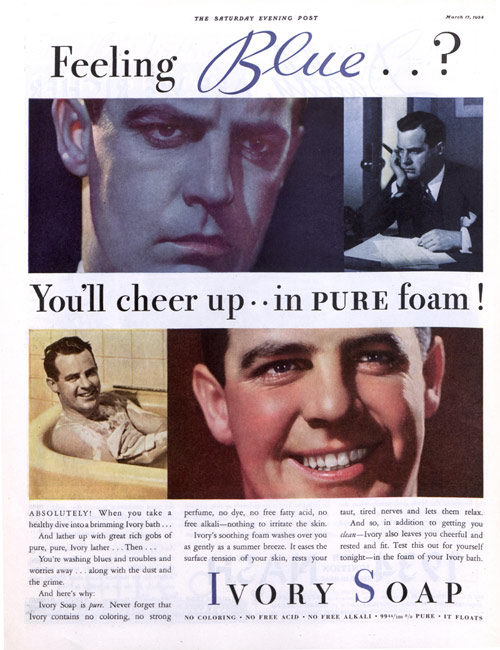

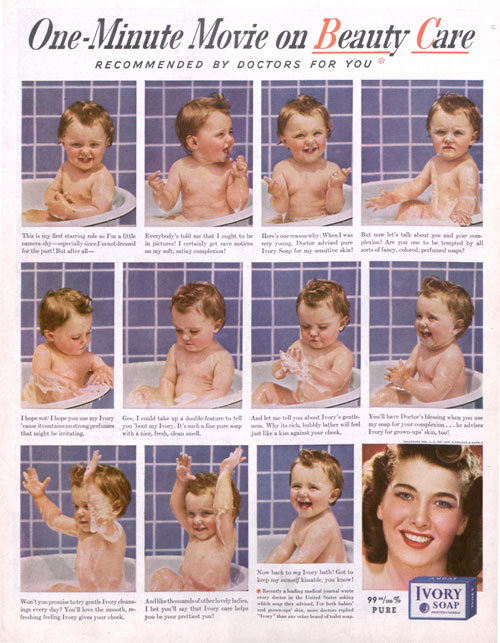

Vintage Ads: Ivory Soap

Ivory Soap was first sold by Procter & Gamble in 1879, and it’s still available today, nearly 140 years later. The Saturday Evening Post has regularly carried Ivory ads throughout its equally long history. While the tactics have changed (one early ad warned Europe-bound travelers to bring their own soap), the basic message never did: Ivory was always “The Soap that Floats” and “99 44/100% Pure.”

(All advertisements copyright © Procter & Gamble)

“It is a mistake to suppose that you can buy good soap ‘anywhere in Europe.’”

“There are two things she will do well to remember: (1.) All men enjoy good meals. (2.) Most men appreciate cleanliness.”

“Professional florists use Ivory Soap in preference to anything else.”

“After a hard hike or muscle-building romp, it certainly will be a pleasure for him to have an old-time bath with the bubbling, copious Ivory lather as he used to have at home.”

“With Ivory as their guardian all through the day, your hands can say nice things about you always!”