She merited a eulogy all her own. Her lifetime of advocacy for those with special needs earned her a reputation far beyond the coincidental fame of being related to two senators and a president.

To fully appreciate the impact Eunice Kennedy Shriver made on our country, we need to understand the fear and misunderstanding that surrounded intellectual disabilities a generation ago. In an article she wrote for The Saturday Evening Post in 1962, she directly addressed this issue, which had become almost unmentionable in society.

“We are just coming out of the dark ages in our handling of this serious national problem. Even within the last several years, there have been known instances where families have committed retarded infants to institutions before they were a month old and ran obituaries in the local papers to spread the belief that they were dead. In this era of atom-splitting and wonder drugs and technological advance, it is still widely assumed—even among some medical people—that the future for the mentally retarded is hopeless.”

She had to address very basic and, to us, almost inconceivable misbeliefs about the mentally handicapped.

“Mort Frankston, director of a work-training center for the retarded in Philadelphia, points up the problem. ‘I still have friends,’ he says, ‘who ask me, “Aren’t you afraid to work around retarded people? Won’t they go berserk?’ This is a misconception which we may as well clear up right now. There are important differences between the mentally retarded and the mentally ill. The vast majority of the mentally retarded are not emotionally disturbed. They do not ‘go berserk.’ They simply lag behind in their intellectual and physical skills, usually from birth. They often strike people as odd in their behavior because the mind of a small child inhabits the body of a much older person.”

Shriver’s involvement with the cause started in childhood with her older sister.

“Rosemary was born September thirteenth at home—a normal delivery. She was a beautiful child, resembling my mother in physical appearance. But early in life Rosemary was different. She was slower to crawl, slower to walk and speak than her two bright brothers. My mother was told she would catch up later, but she never did.

by Eunice Kennedy Shriver

September 22, 1962

“Rosemary was mentally retarded.

“For a long time my family believed that all of us working together could provide my sister with a happy life in our midst. My parents, strong believers in family loyalty, rejected suggestions that Rosemary be sent away to an institution. ‘What can they do for her that her family can’t do better?’ my father would say. ‘We will keep her at home.’ And we did.”

By 1941, though, Rosemary’s condition worsened.

“Rosemary was not making progress but seemed instead to be going backward. At twenty-two she was becoming increasingly irritable and difficult. She became somber and talked less. Her memory and concentration and her judgment were declining. My mother took Rosemary to psychologists and to dozens of doctors. All of them said her condition would not get better and that she would be far happier in an institution where competition was far less and where our numerous activities would not endanger her health. It fills me with sadness to think this change might not have been necessary if we knew then what we know today.”

Shriver’s concern for her sister grew into an awareness of the neglectful, despairing attitude society had developed toward retarded children. She worked to dispel the fear, shame, and ignorance about retarded children. She used the renown that came with being the president’s sister to speak openly and hopefully about the subject. She even managed to get her presidential brother to address the special needs for the mentally handicapped. President Kennedy also pushed through legislation to create The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which continues to study ways of improving infant health.

For all her hope, Eunice was willing to recognize the obstacles these children faced. She spoke of the need for better training, and the opening of job possibilities for mentally challenged adults. She also spoke of the need for the healthy community to seriously address this issue.

“To our surprise and consternation we found out that most doctors and scientists, like the general public, considered mental retardation a hopeless field for research. Established research scientists saw little connection between their studies and mental retardation. Young researchers wanted to do cancer or heart research and get dramatic results.

“We decided to bring the mountain to Mohammed by endowing or building research laboratories in places where ‘our’ problem could not be hidden from the Nobel prizewinners, the young researchers or any other men with ideas. Kennedy Laboratories were established at Massachusetts General Hospital, Johns Hopkins, Wisconsin and Stanford.”

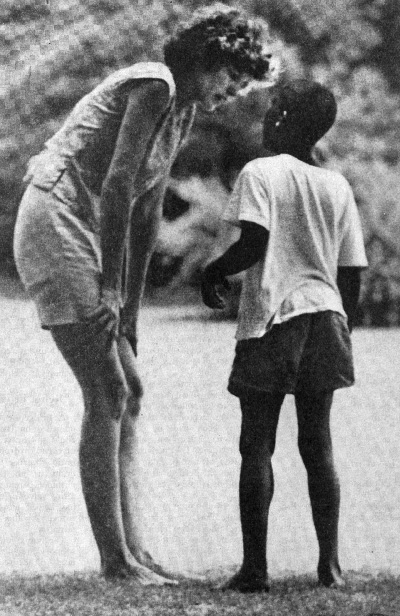

Shriver also launched the Special Olympics program, which gave the world a new view of these children and sparked new understanding and compassion.

Shriver’s words of hope must have gone straight to the heart of parents who struggled to raise a child with special needs.

“Twenty years ago, when my sister entered an institution, it was most unusual for anyone to discuss this problem in terms of hope. But the weary fatalism of those days is no longer justified. The years of indifference and neglect are drawing to a close and the years of research and experiment, faithful study and sustained advance are upon us.”

She concluded her article with a call to others to join the cause and work to improve the lives of the mentally handicapped. Although she was speaking to the public, her words, in retrospect, are highly appropriate for herself.

“To transform promise to reality, the mentally retarded must have champions of their cause, the more so because they are unable to provide their own.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Eunice Shriver was ever bit the leader her brothers were!!!

Eunice Shriver was a blessing for all people.

All of us in the ‘caring’ professions owe an enormous debt to this amazing person. Those who are intellectually disabled now have their needs acknowledged.

She was a giant of a person.

Don Bowen (Sydney, Australia)