Fashion, music, home appliances, automobiles, the economy — with so much changing in American society during the Jazz Age, it’s not surprising that the diets of Americans were changing as well. New foods and new meals were showing up on Americans’ tables.

One big influence was that the stout figure, once admired in the 1900s and 1910s, had become unfashionable. Americans wanted to emulate the trim, athletic young man, or the stick-figure flapper. Dieting became a common theme in the press. Fad diets began sprouting up. People went on the Hay diet, celery diet, or the grapefruit diet. The media reported on how Hollywood starlets lost weight. Hollywood actress Bebe Daniels ostensibly followed an exercise regimen that might have been beyond the average home maker: swimming, fencing, golfing, and horse riding. Another recommended a diet of only lamb chops and pineapple.

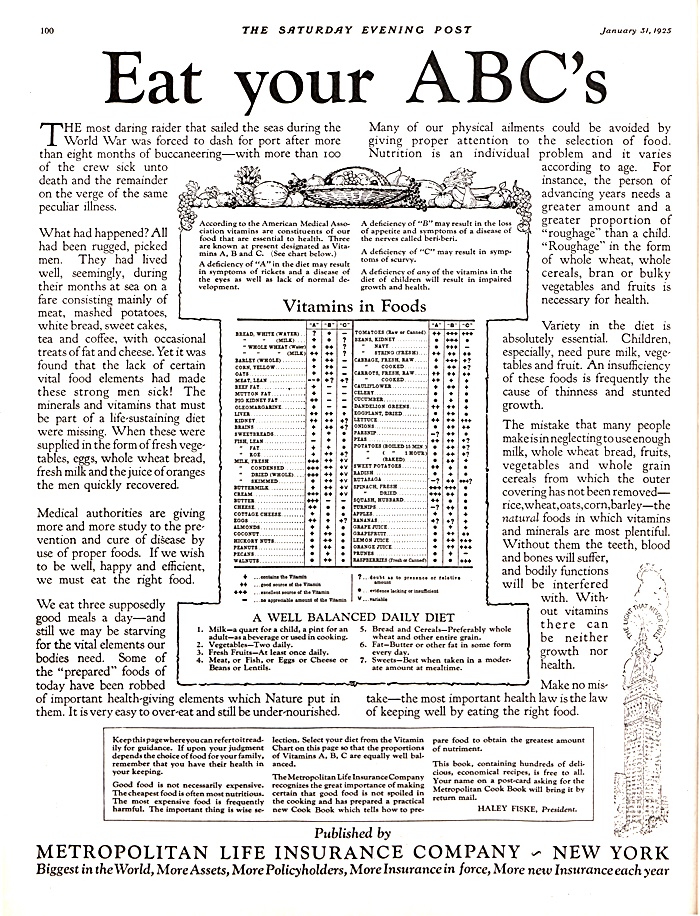

With a new awareness of fattening foods, cooks were cutting back on fats and starches and putting smaller portions on plates. They were also looking for food that was promoted for having vitamins. The term was new and no one was quite sure what they did, but shoppers knew it was something healthy.

Here’s how many family’s meals were changing.

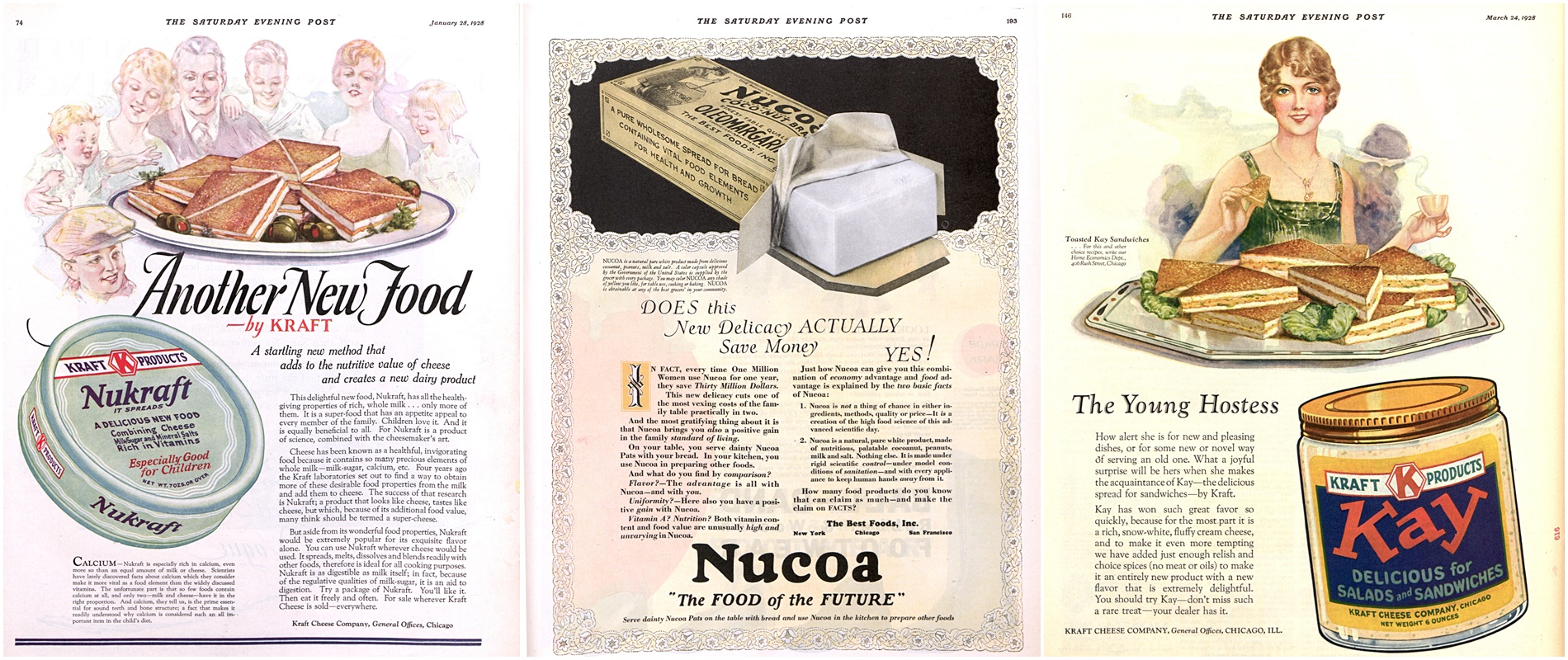

Processed Food

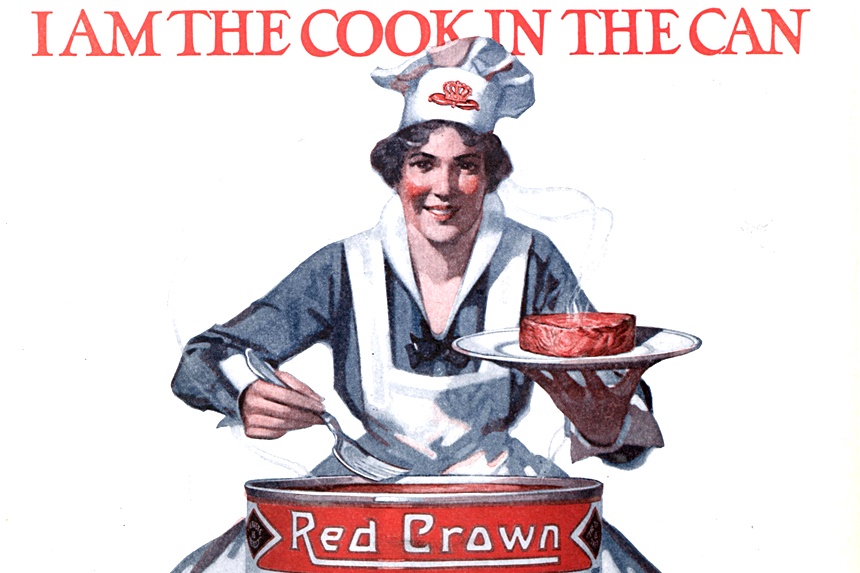

Once, home makers had prepared all meals from basic, raw ingredients. It involved hours of work like shelling peas, peeling potatoes, plucking chickens, creating sauces, and grinding coffee. But now companies were offering ready-to-cook, ready-to-serve entrees, easily and quickly prepared. The biggest manufacturing industry in America was not steel or automobiles, but food processing.

Processed foods made their first big impact on breakfast. Up until the 20th century, traditional morning fare had been meat, potatoes, and more meat. Now Americans were switching to lighter, healthier breakfasts, like an egg, toast, and one of the new, processed breakfast cereals. And food processors kept turning out a growing number of them: Kellogg’s Corn Flakes (1898), Puffed Rice (1909), Post Toasties (1908), bran flakes (1915) Wheaties (1924), and Rice Krispies (1928).

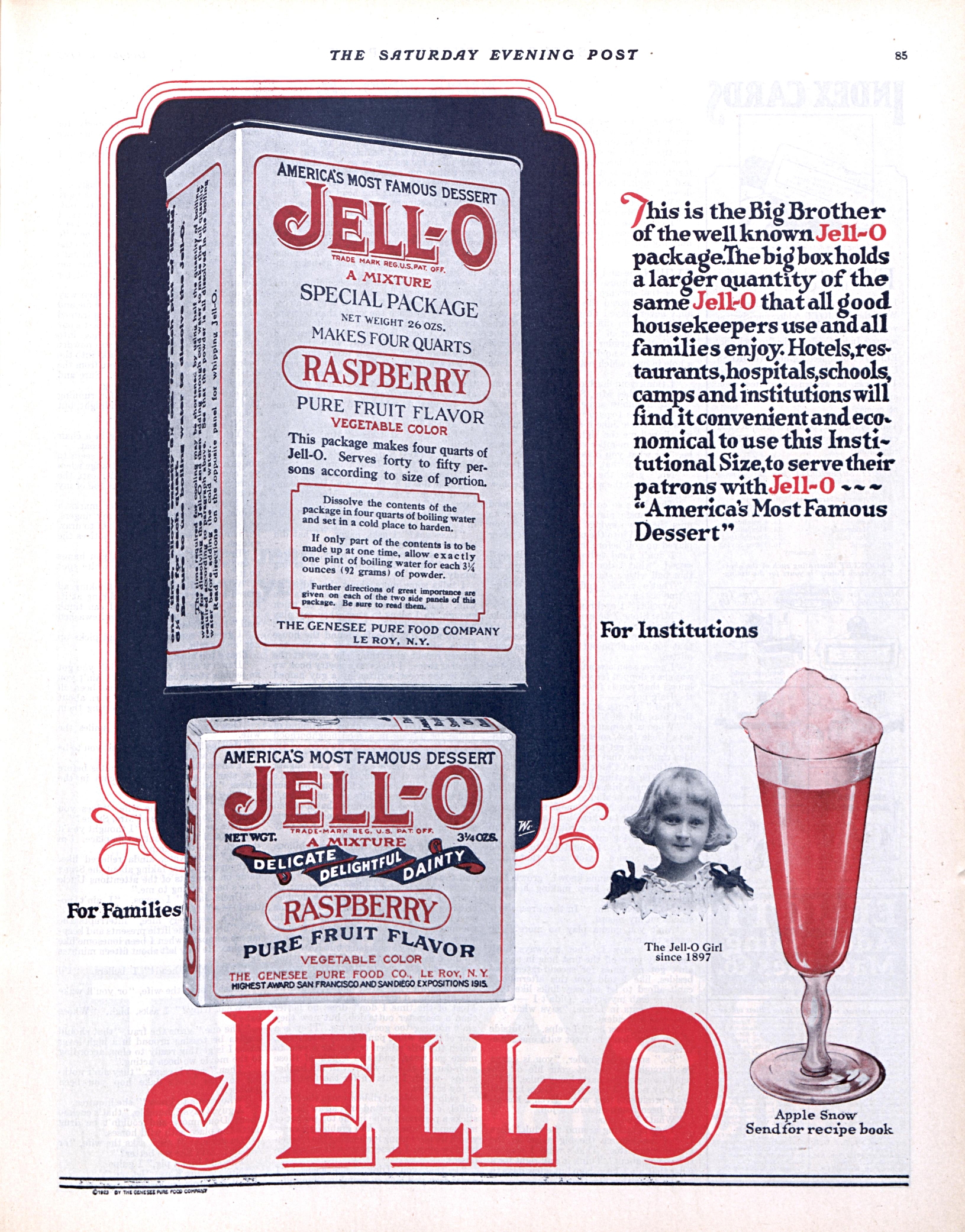

Jell-O-Mania

Salads were a common feature of lunches, along with sandwiches and soup. But the more creative cooks would serve a Jell-O® salad on leaves of lettuce.

Cooks had made gelatins before Jell-O came along, but it had been a long, arduous process. Jell-O — a combination of granulated gelatin, sugar, and fruit flavorings — made it much easier. Jell-O had languished on store shelves for several years until company salesmen began distributing Jell-O cookbooks in 1902. By the 1920s, many home makers were using it to make Jell-O salads. These were dishes often made with the new lime Jell-O, into which was dropped celery, chopped cabbage, red peppers, carrots, nuts, cottage cheese, cream cheese, or fruit cocktail.

Experiments

Thanks to new household appliances like vacuum cleaners, washing machines, and electric irons, home makers had more free time to experiment with new recipes. For the brave-hearted, this meant trying a more difficult dish like bœuf à la Bourguignonne. Sometimes the experiments took bizarre turns, like the salad with popcorn, bananas, and mayonnaise (which was revived not long ago). Or the shepherd’s pie with meat, potatoes, vegetables, and a marshmallow crust. Or an appetizer of fruit cocktail covered with powdered sugar.

New Vittle Venues

One of the first industries to feel the effect of prohibition was fine dining. Gourmet restaurants, which had stayed in business on their profits from alcohol sales, were now being shuttered.

Yet, the number of restaurants tripled in the 1920s. About half were lunchrooms. Cafeterias — where the food was inexpensive and instantly available — were also popular. They offered familiar fare with no gourmet experiments. The owners’ focus was on “quick and clean” service. It was reported in 1927 that about a third of all meals in cities were eaten in restaurants (and most of the diners were women).

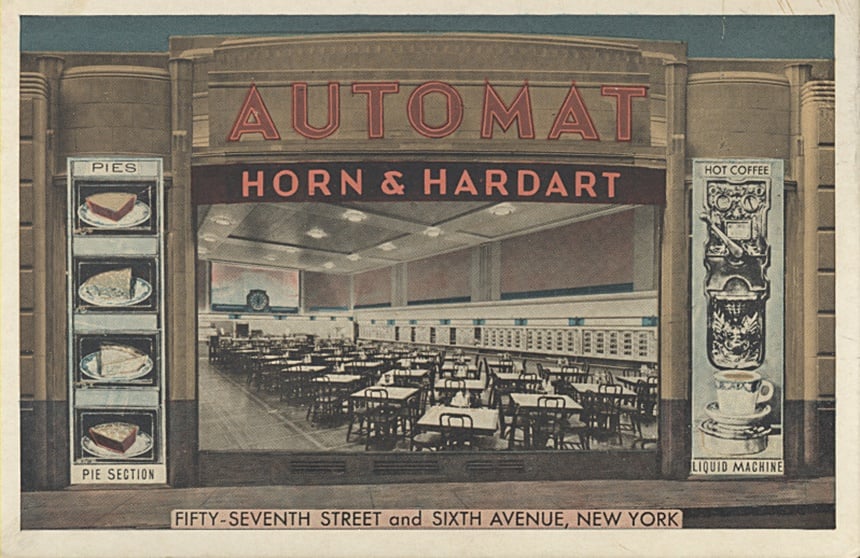

Food was available even faster at automats: self-service systems that dispensed food by machines.

Drive-in restaurants were only getting started in the ’20s. They were typically located on the shoulders of main travelled roads, and, at this time, sold more hot dogs than hamburgers.

Speakeasy Snacks

Before prohibition, many men dined in saloons, where food was set out on the bar for patrons. It wasn’t healthy, but it was free. It might include deviled ham, fish, beef tongue, pickles, radishes, and maybe sandwiches. Patrons suspected the food was of low quality, but they might not have noticed how heavily salted it was to encourage patron to drink more.

Now that serving drinks had gone undercover, free food was offered in the speakeasies. Owners wanted drinkers to have some food in their stomachs to offset the alcohol; an obviously intoxicated client weaving out of a door would attract unwanted attention.

But speakeasy food was a bit more refined, perhaps because only customers with connections (and, hence, password) were admitted.

Customers in the “Speaks” reached for canapes with ham, crab, or caviar garnished with peppers, paprika and lemon juice. Or the bar might offer stuffed mushrooms, crab cakes, egg rolls, meatballs, or deviled eggs. There might also be stuffed celery (with cream cheese mixed with tuna, lobster, crab, olive, or pimento.

The better speakeasy drinks were often mixtures with syrup, bitters, soda, and maybe even with garnishes, all of which helped hide the awful taste of the illegal hooch. These mixed drinks were called cocktails, named, according to some, after the term for cock-(rooster-like) tailed horses of mixed parentage.

In time, these snacks would become mainstays of home cocktail parties when drinking was legitimate again.

Many New York speakeasies introduced Americans to Italian cooking, according to Fashionable Food by Sylvia Lovegren. Italian immigrants had brought their recipes from the old country, but had little opportunity to share them with mainstream America. But when they opened a speakeasy in a basement room, they would serve native dishes cooked on site. With growing popularity, the food came out of hiding and into main-street restaurants. Sicilians who’d been cooking with plain, inexpensive fare in the old country were now encouraged by their American customers to enrich their sauces, be more generous with seasonings, and use more meat.

Incidentally, Chinese food also became more popular in this decade. This might have been due to the American craze for playing the Chinese tile game, Mahjong and because of the introduction of La Choy brand chow mein.

Dinner at Home

Of course, most families still ate dinner at home, cooked by mom. A typical 1920s home-cooked dinner might offer Chicken a La King (a recipe for this dish is found in many 1920s cookbooks) along with vegetables and some sort of salad. Dessert might be icebox cake (cookie wafers inside frozen whipped cream), devil’s food cake, or pineapple upside down cake (encouraged by improvements in the canning process and a rise in pineapple imports from Hawaii).

For after-dinner indigestion, there was Johnson & Johnson digestive tablets. Alka Seltzer wouldn’t arrive until the 1930s.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

TV dinners arrived in the ’50s, along with increasing presence from fast food outlets.

The changes that occurred in regards to all aspects of food had greatly accelerated after World War I in the ’20s, including diners and restaurants of course. The Soda Luncheonette ad I found particularly interesting. After World War II, the changes continued, but unfortunately that included the wide usage of unhealthy artificial ingredients we’re still dealing with to this day. The good news is there is a significant awareness of this problem, and stores like Sprout’s offering healthier versions of a lot of our favorite foods and drinks.

They may still be around and in urban or big-city areas but I like the idea of the AutoMat. Bring them to small towns and rural areas for guys like me who can’t cook. I could do this every evening followed by a dose of digestive tablets.