News of the Week: A Mission to Mars, a Magnum Sequel, and a Mix-Up in Astrology

This is Elon Musk to Major Tom …

Elon Musk doesn’t do things small, and that includes space exploration. This week, the billionaire CEO of SpaceX revealed at the International Astronautical Congress in Mexico his plans to not only fly humans to Mars but also build a self-sustaining city there. It sounds fantastic, but a lot of people are skeptical of the plan, including Bill Nye the Science Guy. He doesn’t think anyone wants to live (and die) on the Red Planet.

Musk says that the first colony ship will be called Heart of Gold, which is the name of a ship in the Douglas Adams classic The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

Lily Magnum, P.I.

I’ve been waiting for a Magnum, P.I. movie for a while. Years ago, Tom Selleck hinted there might be one, maybe even a big-screen adventure written by Tom Clancy; it never came to be.

But we might have a Lily Magnum coming to television. That’s the name of Thomas Magnum’s daughter, and ABC is readying a sequel that will feature her as the lead character trying to solve the mystery of what ended her military career. (The original Magnum, P.I. aired on CBS.)

At first I thought this was a terrible idea, but the more I think about it, the more I like it. It’s better than a full reboot of Magnum, P.I. because then we’d have someone else playing Magnum and the other characters from the original, and it would be updated. As approximately 400 TV show reboots have proven, it just wouldn’t be as good. But with his daughter being the focus of the new show, that means this sequel will actually take place in the same universe as Magnum, P.I., which means the events of that series did happen, and it opens the door for Selleck and his co-stars to make an appearance.

Hopefully, it will be filmed in Hawaii, or what’s the point?

Wait…I’m a Taurus Now?!?

In other space and sky news, everything you believe about astrology (you believe in astrology?) is probably wrong.

NASA freaked everyone out this week when it announced that our astrological signs aren’t the same as they were centuries ago because the constellations have changed, which means that we might not have the astrological sign we thought we had. Also, there are actually 13 zodiac signs. For some reason, we’ve been ignoring Ophiuchus all these years.

But if you believe in and follow astrology, NASA says not to worry. Nothing has really changed. If you’ve always been a Capricorn, well, you can continue to be a Capricorn. In fact, be the best Capricorn you can be!

This isn’t even a new story; it’s only coming around again. I remember this same exact story 5 or 10 years ago, and it caused a hubbub then, too, and everyone was talking about it. I don’t know why repetition of news stories like this irritates me, but as a Gemini, I’m not supposed to get along with Pisces, Cancers, Virgos, or Scorpios, so maybe that has something to do with it.

Cereal Killer

Here’s a side effect of global warming you might not have thought of: the disappearance of Lucky Charms.

That’s the finding of scientists who say that global warming is happening 5,000 times faster than grasses like wheat, rice, barley, and rye can adapt, and in the next 40 years or so, we could see them gone. This would affect the production of cereals. Of course, these grasses are used in a lot more foods than your breakfast cereal, so it could become a major problem worldwide.

Fortunately, it won’t happen until around 2070, so Jerry Seinfeld doesn’t have to freak out.

RIP Agnes Nixon: 1927–2016

I’ll tell you something if you promise to keep it a secret. I watched Guiding Light from 1980 until its final episode in 2009.

Agnes Nixon passed away this week at the age of 93. She wrote for Guiding Light from the late ’50s until the mid-’60s — long before I started watching it — and later went on to create both All My Children and One Life to Live (two other shows I watched because my mother watched them, but they weren’t as good as Guiding Light). She also created Loving and its spinoff The City and produced and wrote for Search for Tomorrow, Another World, and As the World Turns.

There aren’t many soaps on TV these days. They used to rule the daytime, but now only four remain: The Young and the Restless, The Bold and the Beautiful, General Hospital, and Days of Our Lives. The networks got rid of the soaps to fit in more programs like Dr. Phil, The Talk, and those shows where people throw chairs at each other.

RIP Phone Calls

According to Slate, the phone call died in 2007. Which must mean that it’s ghosts or time travelers who keep calling me.

In a piece about what’s lost when telephone calls go away in this age of texting, email, and social media, Slate says that phone calls still live on “in roughly the same way swing dancing lives on, or Latin declension, or manual transmission.” Now, maybe I’m living in a bubble (one where I don’t know what Latin declension is), but have people really stopped making and receiving phone calls that much? (Also, there are plenty of cars with manual transmission.)

Nielsen says that in 2007, the average monthly number of texts was more than the average monthly number of phone calls. And those text numbers are probably even greater in 2016. Everyone has a mobile phone now, and many people have gotten rid of their landlines. If you’re in your 20s, there’s a very good chance you’ve never even had a landline. And if you notice, a lot of people don’t actually make phone calls anymore on these devices; they’re just texting. Texting, texting, texting, texting, texting all day long.

The Slate article is worth reading, though, especially the section where the writer talks about how phone etiquette has changed, how our expectations regarding phone calls have changed, and how these new rules affect our relationships in ways we might not even think of.

Is it weird that I don’t think I’ve ever sent or received a text and that I still love and use an answering machine? I still have my landline too, and I plan to keep it until the phone company comes and rips it out of my wall and arrests me for communication nostalgia.

This Week in History: First American Newspaper Published (September 25, 1690)

Publick Occurrences Both Foreign and Domestick — which would make for a great album title — was the first multipage newspaper published in the United States (before that, newspapers were one page). It was edited by Benjamin Harris and was launched in Boston, Massachusetts.

This Week in History: George Gershwin Born (September 26, 1898)

The writer of songs like “Rhapsody in Blue” and “An American in Paris” and the opera Porgy & Bess was born in Brooklyn, New York. He was only 38 years old when he died, and it’s rather amazing what he did in such a short time.

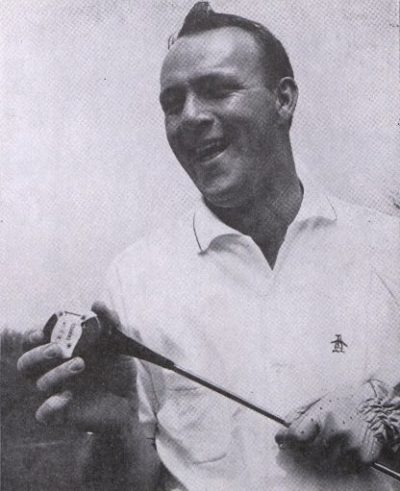

The Arnold Palmer

In honor of golfer Arnold Palmer, who passed away this week at the age of 87, here’s the recipe for the drink he invented in 1960 while playing at the U.S. Open in Denver, Colorado. Palmer liked it this way: three parts unsweetened tea mixed with one part lemonade. A lot of people like it with half tea and half lemonade, and if you do it that way it’s called a Half & Half.

National Homemade Cookies Day

Saturday is National Homemade Cookies Day. Here’s a recipe for Cherry Oatmeal Cookies, and here’s one for Cream Cheese Cookies. Hallmark Channel has several recipes for the day, including Pumpkin Walnut Cookies.

If you just don’t have the time to make them yourself, you can always buy some Girl Scout cookies. You can even find out which one pairs best with your astrological sign — unless your sign is Ophiuchus.

Of course, it says my favorite cookie should be the Tagalong. Oh please. I’m a Samoa guy all the way.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Supreme Court term starts (October 3)

Cases the Court will be looking at this term involve Apple, service dogs, religious schools, and cheerleader outfits.

Customer Service Week (October 3–7)

Yup, this is the week we honor all those who help us, so call up a customer service rep on the phone and talk to them for 30 or 40 minutes.

Vice Presidential debate (October 4)

Governor Mike Pence and Senator Tim Kaine square off this Tuesday at 9 p.m. ET at Longwood University in Farmville, Virginia. The moderator is Elaine Quijano of CBS.

The Belles of the Brawl

The football game is the place to be in Huntsville on Friday night, but my sorry butt isn’t in those bleachers. Blair guilt-tripped me into babysitting Grandma instead. So here I am, stuck in a muggy warehouse on the outskirts of town, biding my time while “Gram” hangs out with her friends.

The crowd erupts in a chorus of cheers and boos. I close my eyes and rub my temples, reminding myself that I’m doing the right thing. “Your grandma isn’t as young as she thinks she is,” Blair said as she packed the minivan just a few hours earlier. “I’m counting on you to look out for her.” The kiss of death came when she gave me the look. You know, the one moms everywhere use to make you feel all crappy and selfish for wanting to do your own thing. “I’m working, Mary, or else I’d be there.” Her harp snug and secure, she closed the trunk and headed for the driver’s seat. “Besides, if you kept an open mind, I bet you’d even have a little fun.” With that, she’d blown me a kiss and pulled out of the drive.

I snort at the memory. Big. Fat. Chance. Watching a group of chicks skate around a beat-up old rink isn’t exactly my idea of a killer time. Still, I’d rather sacrifice an evening here than spend the entire weekend at a highlands festival with Blair. My bright red hair serves as a constant reminder of my heritage. I don’t need to traipse around a field in period garb, warding off a bagpipe-induced headache, to feel connected to my roots.

A huge guy with more piercings and tattoos than I can count accidentally elbows me in the face as he tries to squeeze past. “Sorry, hun!” he pats my arm apologetically as I tenderly probe my forehead. Great. I can already feel the beginnings of a goose egg.

Time to drown my sorrows in Diet Coke and sour Skittles. I clank down the bleachers and head for the concession stand. The skaters round a bend in the track, pushing and snarling at each another as they roll past. Cyndi Lauper blares from the loudspeakers, and I cut wide to avoid the team mascot, a panther attempting to pump his arms and jerk his hips in time with the music. It’s kinda funny, but I can’t afford to stick around and watch. The last time I got stuck on grandma duty, I swear the thing stalked me. Twice I turned around to find it standing right behind me, breathing all heavy and staring at me with those creepy yellow eyes.

The comforting smell of warm butter and nacho cheese sauce washes over me and I sigh in relief. I shove a crumpled $5 bill at the sleepy-eyed attendant and place my order. While he shuffles off, I drum my fingers on the countertop and look at the clock. My heart sinks. It’s not even halftime yet.

Four sharp whistle blasts pierce the air, followed by a roar from the crowd. Someone just got fowled big time. I cast a quick glance over my shoulder, but the bleachers block my view of the track.

Finally, cantina boy hands over the goods. Sugary remedy in hand, I turn around only to smack straight into a wall of fur. Soda drenches my shirt and my candy goes soaring. Thinking black thoughts, I cross my arms and wait for the jerk to apologize.

The mascot removes his feline head, and I think I might die. It’s Nick Abbot. Nick freaking Abbot! He’s a junior, the hands-down heartthrob of St. Bartholomew High. My mouth falls open, and my face burns with heat. He’s saying something, but I can’t make sense of the words. It’s like I’ve fallen into a weird, alternate reality. Beautiful Nick, with his devastatingly blue eyes and linebacker physique is the mascot? And he’s here? Talking to me?

“Mary.” He grabs my shoulders with his oversized paws and shakes. “Mary Calhoun.”

“Whaaaaa…” I croak, shocked that he actually knows my name.

He gives me a confused look.

I snap my mouth closed and curse my awkwardness.

“Sorry to scare you,” he tries again. “But you gotta come quick. Its your grandma.”

“What?” My head clears as the stars instantly fall from my eyes. “What happened?”

“One of the She Devils gave her one heck of a J-block.”

I give him a blank stare.

“Your grandma is hurt. She got body slammed by a girl from the other team.” He takes my hand in his giant paw and leads me to the rink.

I shove past the spectators and climb over the rail onto the slick banked track. My grandmother is on the ground, surrounded by her teammates. Please be okay please be okay, I chant over and over again in a silent prayer. My breath hitches in my chest, and I fall to my knees by her side, but she’s … smiling?

“Mary, darling,” she purrs and pets my arm. “I’m fine! Just took a wee tumble.” Her hair pokes out in wild bright red tufts from under her helmet, which sits askew on her dainty little head.

“Can you get up?” I ask apprehensively. Her thin legs are tie-dyed with bruises.

“No need.” She waves her hand dismissively. “That handsome young man will carry me,” she says, pointing at Nick.

“Sure thing, Gram Slam,” Nick replies cheerily. The rest of the team looks on with concern as he scoops her up in one swift movement.

My grandma bats her eyelashes.

I bite the inside of my cheek. Oh God. She’s hitting on him. I glare at her in silent reprimand.

She ignores me and leans against his chest, only to jerk back with a frown. “You’re all wet and sticky, dearie.”

Nick shoots me an amused look over her helmet. My face burns. I guess some of my soda hit him, too.

“Put me next to the action,” she commands, pointing a sparkly black fingernail at the base of the bleachers.

Nick hesitates. “Gram, I think —”

“I will cheer on my team.” She scowls at him, her bright red false lashes and sparkly eye shadow making her look like a crazed, elderly fairy. “The doctor can wait.” She sets her fuchsia lips in a firm line.

Nick shakes his head, his oh-so-kissable mouth splitting into a crooked smile. I watch with a mixture of horror and relief as the boy I’ve been crushing on for the past year carries my cougar of a grandmother to the sidelines.

A tap on my shoulder brings me back to my senses. I turn to face a massive woman with a wicked-looking eyebrow ring.

“Okay, Mary, you’re up,” barks Lady Harmalade, the team captain.

“What?” I ask, tilting my head to look up at her.

“You heard me. We need five gals on the track at all times. Ferocia has a bum knee, and Katie Karnage is out with a stomach bug. You’re our only back up.”

I look over her shoulder to see the two women in question leaning on each other as they hobble to the exit.

“Me?” My voice shoots up a few octaves, and my legs wobble. “Out there?” I vehemently shake my head. No. Fricking. Way.

“You’ll do fine. You’re here almost every other weekend, so I know you know the rules.”

She towers over me, hands on hips. I stare at the glittery pink team name — Belles of the Brawl — emblazoned on her skin-tight tank top. Her six-pack is visible through the thin fabric, and her biceps are big enough to crush my skull in a single curl.

“Well?” she demands, tapping the toe of her neon pink and green roller skate against the wooden floor with impatience.

“I … I’m not that coordinated,” I protest, casting my eyes about the room as I fumble for a plausible excuse. “And I haven’t skated in ages …”

Harmalade rolls her eyes at my excuses. “Go suit up.” She jerks her chin toward the locker room. “Just switch clothes with Gram … you guys are about the same size.”

I open my mouth to make a final plea, but she’s already turning away, clapping her hands to call a huddle with the other Belles.

Shell-shocked, I stand there staring at the track until a gentle voice murmurs in my ear and a big furry paw guides me toward the restroom. Nick. Sultry, unattainable Nick is actually helping me. I pinch the inside of my wrist; this has to be a dream.

“You’re gonna do great,” he gushes with excitement as he deposits me by the bathroom door. “It’s simple. Use your shoulders, butt, or hips to block. Do whatever you can to stop the girl with the star on her helmet from making it through.”

Easy for him to say. I don’t stand a chance against those raging glamazons. I blink and wipe my hands on my jeans.

“Sorry, you probably knew that already.” He shrugs, his gaze darting between my face and his feet. “I mean, you’re always here, and your grandma is just the coolest …” His voice trails off and he rubs his paws together nervously.

I nod, despite my confusion. My grandma? Cool?

“Well, better hurry,” he says in a rush. “I told Spanx I’d bring more Gatorade. Can’t keep my big sis waiting.” He runs off before my brain can signal my mouth to speak.

I take a deep breath and step into the locker room. As I don the ridiculous uniform my grandma chatters on and on, offering tips and reminding me of the rules, but I can’t focus on her advice. The words slide over me as I concentrate on keeping my fingers from shaking. Falling on my face while clad in sparkly fuchsia booty shorts would be plenty embarrassing, but with Nick there to witness my glittery demise, I could practically hear the nails being pounded into my coffin. Social. Suicide. I put on the knee-high pink socks, the black kneepads, and the neon green roller skates. Grandma tosses me her tank top, a little black thing emblazoned with rhinestones and the team name in pink cursive lettering. The back of the jersey sports her roller name, Gram Slam.

Soon I’m lining up on the track with the other girls. The Belles smile at me through their mouth guards, at once terrifying and beautiful. I accidentally make eye contact with the She Devil next to me, who grimaces and runs a finger over her throat in a cutting motion. That’s it. I’m gonna die. Or throw up.

The players around me still, their muscles tightly coiled in anticipation of the whistle.

I cast a wary glance to the sideline where Nick leans on the track’s railing, his chin atop his hairy cat arms. Gram sits beside him, legs propped up on a chair. He catches my eye and winks. My heart, already frantic with worry, skips a beat. Gram blows me a kiss and then whips her head around to flip off a passing She Devil.

The whistle sounds and my guts jump into my throat, but I somehow manage to remain upright. I make it a quarter of the way around the track before realizing I’m not half bad. I just need to take it one lap at a time. I narrow my eyes and focus on the Belle in front of me. It’s Nick’s sister, Spanx. She could level an opponent with one bump of her brutal booty, and I don’t want to be caught anywhere near that action.

Suddenly, a sharp blow to the side has me stumbling forward. Once I regain my balance, I snap my head around to find the same She Devil who threatened me. Her black lips twist into a nasty sneer, and I realize she’s snuck in an illegal hit.

But … I’m not doing too great at watching her and watching my feet at the same time. My skate catches and I trip into her, arms outstretched. I close my eyes and brace for impact, the She Devil’s crazed scream filling my ears. Another elbow pokes my side and a knee rams me in the back, but the fall isn’t as bad as I’d anticipated.

I crack one eye open to find I’ve somehow taken two She Devils down with me. Two! They lay there, pounding the floor and wailing as the pack speeds past, leaving us behind. I scramble to my feet, eager to avoid getting run over as the pack comes back around. In the next instant, however, the She Devil’s jammer makes it through to the front of the line, and the ref blows his whistle to stop the play.

We line back up again, and I lose track of time. Round and round we go, a blur of sweat and shouts and hunger. I fall again. I get up again. A She Devil makes a nasty comment about Gram, so I hip check her. This isn’t so bad. I catch myself smiling. The whistle sounds for halftime, and the Belles pull me into the hurdle. They pat my back, congratulate each other, and down thirsty mouthfuls of Gatorade between grins. My whole body tingles with the high of competition. It seems like only seconds pass before the buzzer sounds, telling us to line up for round two.

The rest of the night passes in a haze of unexpected happiness. We don’t win, but I’m too elated to care. I shake hands with the She Devils, and then turn to the sidelines to find Gram. The minute my skates touch the cracked cement of the warehouse floor, she springs up from her chair and comes flying, arms outstretched.

“That’s my girl!” she screeches, enveloping me in a hug so tight it’s hard to breathe.

I step back and give her a long look. She bounces in place, beaming from ear to ear. “How’s your leg?”

“Oh … that.” She stills and gives me a sheepish look. “Well, you never can be too careful at my age.”

“Looks to me like you could’ve skated just fine.”

“Looks like you had fun.” She glances past me, her voice dropping to a whisper. “And it looks like you have an admirer, too.” She turns on her heel and struts off to find her teammates.

I turn to find Nick, sans costume this time. My mouth goes dry.

“Hey.” He shoves his hands into the back pockets of his jeans. “You were great out there, Mary.” He smiles tentatively.

“Oh, uh … thanks.” I tug at the hem of my shorts and try to come up with something else to say.

“The uni looks good on you, too.” A slow red creeps up his neck to his ears. “You’ll need a roller name though,” he babbles on, trying to cover the awkwardness between us. “For your jersey, I mean …”

At that moment, Lady Harmalade and the rest of the team roll up. “Mary, Queen of Knocks!” She bellows in an awful imitation of a Scottish accent before giving an extravagant bow. The other girls follow her lead, bowing and curtseying with mock adoration.

“That’s perfect!” Nick nods, his smile more relaxed this time.

“So?” Gram arches her eyebrow. “You Scots enough to be a Brawler?”

I throw back my head and laugh. “Only if I can tie the tartan ’round my arm.”

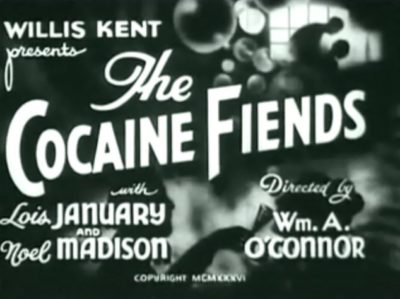

Long before Trump: The Unsettling Popularity of Huey Long

The 2016 presidential campaign season doesn’t have a monopoly on charismatic, polarizing candidates with unconventional political ideas. Although this election cycle is legitimately unprecedented in a number of ways, the presentation of radical policies isn’t one of them.

One such presidential hopeful with radical ideas appeared in the 1930s. Louisiana senator and former governor Huey “The Kingfish” Long felt President Roosevelt hadn’t gone far enough to address income inequality. Claiming that 2 percent of Americans owned 60 percent of the wealth, he proposed a “Share Our Wealth” program to put more money into the hands of the poor.

Long argued that no family should earn more than 300 times the average income nor hold more than 300 times the wealth of the average American fortune. Under his program, the government would tax all incomes over $1 million on a rising scale, so that any income greater than $8 million would be taxed at 100 percent. The program also guaranteed every family a homestead valued no less than $5,000 and an annual income of $2,000 (one-third the average family income, according to Long).

Long, whom The Washington Post called “the most entertaining tyrant in American history,” came up with this plan in 1934 while weighing a run for the White House. To gauge voter support, he sent Rev. Gerald Smith across the south to start Share Our Wealth clubs. The response was so enthusiastic that by 1935, 27,000 clubs had been formed and 4.6 million members had signed up.

Though he was solidly supported by impoverished Southern voters, who felt they had a champion in the senator, Republican and Democratic politicians, alarmed by his dictatorial style as governor and his growing popularity, considered Long a threat.

The threat was removed on September 10, 1935, when Huey Long was killed by an assassin’s bullet.

In a biographical sketch written for the Post, and excerpted below, Hermann B. Deutsch detailed several of Long’s bolder political maneuvers, some of which skirted the law. The author conceded that Long brought improvements to the state and redistributed some of his state’s wealth, but Deutsch still considered him a “benevolent despot.”

Huey Long — The Last Phase

By Hermann B. Deutsch

Excerpted from an article originally published on October 12, 1935

The political history of Huey P. Long embraced three cycles which, though interlocking, preserve separate identities in time and space. For convenience they may be labeled: Louisiana, Washington, and Share the Wealth. Each had its share in making the others possible. Each contributed toward the absolute control his laws gave him over Louisiana, just as this control made it possible for all three to continue to function.

In all three cycles, Huey Long exacted unquestioned recognition of his authority.

“The only kind of a band in which Huey Long can play,” Marshall Ballard, editor of The Item, once observed, “is a one-man band.”

From top to bottom, the Long political machine was composed of those who acknowledged his absolute leadership and would dance to any tune of his piping. He asked no more of them and would accept no less. For those who refused, he passed this year the amazing series of laws in seven special sessions of his legislature which constitute what has been termed his Putsch-Over.

The rank and file of the Huey Long political army in Louisiana was content to let him run the whole show because he won battles, and thus led them to the Promised Land of Patronage. The followers of Long the Apostle were content to overlook the practical manifestations of the sublimated precinct politician.

Touching Off a Bombshell

When Huey Long became governor of Louisiana in 1928, the two principal proposals of his program were an increase in the severance tax on natural resources to provide free textbooks for all school children, and an increase of the gasoline tax from one to two cents a gallon — it is seven cents a gallon today — the additional cent to be funded into bonds for the purpose of paving the main highways of the state.

Both proposals were bitterly attacked by the anti-Long politicians; the former on the ground that the state’s money was being dedicated to private institutions in supplying free textbooks to private and parochial schools; the latter because there was no guarantee that the bond money would be expended in actual road construction and not merely in swelling the payrolls of the highway commission for political purposes.

The schoolbook law was validated by the Supreme Court of the United States. The gasoline-tax bond issue was validated by an overwhelming vote of the people, who were heartily sick of gravel highways, and who turned a deaf ear to the sound argument that the fulfillment of so ambitious a plan on the money available was a physical impossibility. Each community hoped that its roads would be paved, and devil take the hindmost.

However, it soon became evident that more money must be provided for the state treasury. Thus, 10 or 11 months after his inauguration, Governor Long called the legislature into special session to levy a tax of five cents a barrel on the business of refining petroleum products, to “enable us to take care of the sick, the halt, and the blind in our state institutions, and of the children in our schools.”

The target of this tax was Mr. Long’s ancient bête noire, the Standard Oil Company, which maintained a huge refinery just outside of Baton Rouge, an industry which at that time maintained a payroll numbering some 7,000 persons. The company promptly announced that the imposition of such a tax would force them to close their Louisiana plant, and immediately began to curtail operations. Along with this there was a roar of protest from all sections of the state. Manufacturers, accustomed to special inducements to bring payrolls and industries into a state, rose up in arms. It became evident almost at once that Mr. Long would not be able to muster a legislative majority for his tax, and, alarmed by a rising tide of personal opposition, he decided to adjourn the session. Anti-administration leaders, on the other hand, insisted there be no adjournment until the legislature had gone on record as opposing any tax on industry.

In order to shut off all such debate, Speaker John Fournet, of the House, had been instructed to recognize only the administration floor leader when the House met, and put the question of adjournment at once. When the chamber convened, the roll was called for a record of those present. This was done by an electrical voting machine which automatically locked until photostatic copies of the vote had been made. During this interval, the chaplain intoned a brief prayer. The moment the final “Amen!” was uttered, all bedlam broke loose. Amid the din, the Speaker put the adjournment motion, which no human being could hear in the hubbub, and the electrical voting machine was once more opened. The whole thing occurred so quickly, however, that the machine was still in the position of the “present” vote of a few moments before, and consequently, regardless of whether members voted yes or no, the machine flashed “yes.”

That fired the powder train. The house went into a riot. Half a dozen fist fights broke out. Members charged the Speaker’s dais. One of them was knocked down and his scalp laid open by a blow. At the height of the tumult, Representative Mason Spencer, of Tallulah, made his way to the front of the House and bellowed:

“In the name of sanity and common sense!”

Legislative Hairsplitting

The rioting was momentarily checked. In the lull, Spencer called on the Speaker to take another vote of adjournment, but the latter refused, declaring the House was already adjourned. Before this could bring on a fresh outburst, Spencer declared he would call the roll himself. He did so, and the vote stood 72 to 7 against adjournment. All but that handful of administration adherents hastened to disclaim any connection with what was then assumed to have been some sort of fraudulent vote-machine operation. Further action was deferred until the following day, when a resolution of impeachment, setting forth 19 specific counts, was filed with the House. A committee of inquiry was appointed, a series of hearings was conducted, and in the end, eight impeachment counts were adopted and sent to the Senate for trial.

The special legislative session had been called for but 15 days, and only one count was voted before the expiration of that period. Over the protest of the Long floor leaders, and on the theory that once it became a court of impeachment, the Assembly was no longer bound by legislative limitations, the lawmakers continued in session until the remaining counts were disposed of.

A New Word in Louisiana

The one passed on before the expiration of the original session limit was voted down by the Senate, where graver charges were still to be taken up. On the following day, however, a remarkable document was laid before that body: A round robin signed by 15 senators — two more than enough to block a two-thirds conviction — to the effect that since all charges voted after the expiration of the legislative time limit were, in the opinion of the signers, illegal, they would refuse to vote conviction on any of them, regardless of evidence. That ended the impeachment proceeding between clock ticks and added the word Robineer to Louisiana’s political vocabulary.

Far from being chastened by this experience, Mr. Long immediately announced he intended to “grow me a new crop of legislators.” To this end he initiated recall proceedings against those who had opposed him. Anti-Long leaders from all parts of the state delivered a counter to this thrust by meeting in New Orleans to organize the Constitutional League, dedicated to the restoration of constitutional government. Mr. Long promptly labeled it the Constipational League, and declared it was composed of those who sought to sacrifice the schoolchildren, the halt, the sick, and the blind on the altars of the Standard Oil Company.

Nonetheless, the courts ultimately upheld the League’s contention that the recall provisions of the constitution did not apply to legislators. The League further brought suit to compel those pro-Long legislators who held highly remunerative places on the state payroll, such as special attorney for the highway commission or warden of the state penitentiary, to vacate either the positions or their legislative seats. This, too, was upheld by the Supreme Court. The following day, 18 pro-Long legislators resigned state jobs.

Ultimately the business interests of the state stepped in to insist upon a political truce. One of its terms was a pledge by Governor Long to impose no manufacturers’ license tax during his term. In return, the business interests were to cooperate with him in a survey on how to raise money for the more effective conduct of state institutions.

Mr. Long’s idea of what the state needed was a great program of public expenditures. This was early in 1930. Pundits still declared oracularly that prosperity was just around the corner. Mr. Long’s position was that all effects of the depression could be fended off from Louisiana if $100,000,000 or so were devoted to permanent public improvements.

The requisite funds were to be raised by adding three cents a gallon to the gasoline tax, dedicating one cent for division between the port of New Orleans and the public-school system of the state, and funding the remaining two cents a gallon, and certain other taxes, into bonds.

The opposition immediately protested that this would do no more than place at the disposal of Huey Long a $100,000,000 fund with which so accomplished a spoilsman might well consolidate his political machine for the state elections of 1932, and thus perpetuate himself in power. Once again the demand was for “safeguards” to keep the money from being politicalized.

The legislature met in May 1930; and a nagging, dragging session it was. Governor Long had won over to his standard, after the impeachment of the preceding spring, a majority of the members, but not a two-thirds majority. Yet the bond issues he contemplated could not be put into effect without constitutional amendments, which required a two-thirds vote of both legislative houses. Since no constitutional amendment could be passed, His Excellency shrewdly hit upon the amazingly simple expedient of calling a constitutional convention, which could be done by a simple majority, to rewrite the entire organic law so as to include the desired amendments. Under the terms of the proposed call, he would control a majority of the delegates.

The opposition could not block a majority vote. So the anti-Long leaders began a sort of “strike on the job,” arguing endlessly among themselves over unimportant pending measures, to keep what was by that time dubbed the “con-con bill” from coming to a vote; but it was finally passed and sent to the Senate for action, with just about enough time left to get it through that body before the expiration of the session.

The Senatorial Toga

In the Senate, however, matters were on a different footing. Here the presiding officer was Lieutenant Governor Paul Cyr, a dentist, who, though elected on the Long ticket, was now one of Huey Long’s bitterest foes. Doctor Cyr made it possible for a filibuster to keep the con-con bill from coming up for consideration in the upper chamber, so that it died on the calendar. The day the legislature adjourned, Mr. Long announced his candidacy for the United States Senate.

“My platform,” he said in effect, “will be the public-improvement program that the people want, but that the legislature killed. If I am elected, that will mean the people approve my program. If I am defeated, that will mean they approve the action of my enemies. But … when I am elected I will not go to the Senate until after my term as governor is finished. I will not permit Paul Cyr to serve as governor of Louisiana for one holy minute. This will mean that one Senate seat from Louisiana will be vacant for two years, but that will make no difference. It has been vacant ever since the man who now holds it was elected.”

And so the issue was fought out. The Constitutional League supported Senator Joseph Ransdell for reelection, and rallied the anti-Long forces to the cause. Mr. Long jeered at the efforts of the Constipational League, spoke of its candidate as “Feather Duster” — a reference to the latter’s neat little brush of a white beard — and said that “the elements trying to defeat me and keep me from paving your roads and building up the prosperity of this state are the same old Standard Oil crowd that tried to keep me from giving your children free schoolbooks, and improving the hospitals, the insane asylums, and the other state institutions.”

“A St. Bernard Count”

The campaign was different from the gubernatorial race of two years before. At that time, Huey Long had had no political organization; only a personal following. The city machine had been aligned with one of his opponents and the state machine with the other. Now he had his own state machine, a vastly improved model of power and efficiency.

Long defeated Ransdell for the Senate by the overwhelming tally of 149,640 to 111,451. One rather unusual feature was the vote of St. Bernard Parish, which adjoins New Orleans on the downstream side. Mr. Long received 3,979 votes there, as against Senator Ransdell’s total of 9. This was the year 1930. A census had just been completed. Yet one ward in St. Bernard Parish, where the census listed a total population of 912 — men, women, and babies, nonvoting Negroes as well as whites — counted 913 votes, all of them for Mr. Long. This added still another expression to Louisiana’s political vocabulary. It is: “A St. Bernard count.” However, Huey Long would have been overwhelmingly elected even if every St. Bernard ballot had been thrown out. Thus, none of the reformers who later clamored for other election investigations raised their voices at this time. There was also a general feeling that “the people have spoken.” At any rate, all opposition to the Long proposals was withdrawn.

A special session of the legislature was called at once, and in a shrewdly worded opening message, the governor suggested that “if we must fight, let’s all fight for only 30 days on full stomachs 15 months hence, instead of starving ourselves while we fight for 16 months between now and the next election.” As an earnest of his readiness to let bygones be bygones, he stood by his original proposals to finance a Mississippi River bridge and aid the New Orleans port authority out of new gasoline taxes, and to give Baton Rouge a $5,000,000 new capitol. The only condition he made was that the impeachment charges, still technically pending against him, be withdrawn. Some 20 die-hards in the House refused to accede to this, but the overwhelming majority did, and thus one stormy chapter was closed.

The legislative program went over with scarcely a hitch, and the era of construction began. There was considerable eagerness to get some of the bond money into circulation, for 1931 was a dreadful cotton year, marked by a 10,000,000-bale carry-over, a record crop, and a price of five and six cents a pound for staple that had cost eight cents a pound by the time it left the gin. Proposals for acreage reduction, for plowing under every third row of the current crop, and similar curative measures were suggested. While the agitation was at its height, Governor Long proposed a law forbidding the growing or ginning of any cotton at all during 1932, the law to become effective when enacted by states representing three-fourths of the country’s cotton production.

At a conference of delegates from cotton states, Senator-Governor Long explained that acreage-reduction laws could be invalidated by the no-cotton law, if enacted as a measure to control the boll weevil or check the spread of root rot would be maintained. Texas, representing one-third of the country’s cotton production, was called upon to be the first to enact the holiday plan, since, if Texas rejected it, there would be no possibility of securing the requisite three-fourths concurrence.

However, Texas refused concurrence, which evoked from Louisiana’s executive the public statement that “Texas legislators were bought to kill the cotton-holiday plan like you’d buy a slot machine.” Mississippi likewise refused. Both passed acreage-reduction laws which came to nothing.

Two Men in One Chair

Meanwhile, Mr. Long found other fish to fry in Doctor Cyr’s sudden move to seize the governor’s chair, on the allegation that Huey Long had vacated it when he forwarded the credentials of his election to the United States Senate. To lend point to this contention, Doctor Cyr took oath as governor before the clerk of court of Caddo Parish, October 13, 1931.

The Statehouse immediately became an armed camp under constant highway police and militia guard, to keep Doctor Cyr from taking physical possession. For the rest, Huey Long chuckled joyously and said: “We’re going to send the Doc back to his tooth shop in Jeanerette now. By taking oath as governor, he vacated the office of lieutenant governor. That means I can go to Washington as soon as the courts settle him.”

The amused regard of the entire nation was focused on Louisiana during the legalistic marches and countermarches that followed. Unemployed men in parks and along water fronts whiled away the tedium of waiting for prosperity by administering to one another the oath of office as governor of Louisiana. Alvin O. King, president pro tempore of the state Senate, was sworn in by the Long administration as lieutenant governor; and the moment the Supreme Court upheld this step, Mr. Long hastened to Washington to take his seat in the Senate, just 17 months after his election to that body. On the same day, in a Statehouse surrounded by militiamen, Lieutenant Governor King became governor. Doctor Cyr continued his protests, and went so far as to open “executive offices” in a Baton Rouge hotel, from which point he issued a proclamation calling upon Mr. King forthwith to abandon the “armed insurrection he was maintaining” at the statehouse. But the move was little more than a gesture, for by that time the entire Long ticket had been elected by something very like a landslide, and was awaiting inauguration in May.

The First Step in Wealth-Sharing

The new governor was Oscar Kelley Allen, boyhood friend of Senator Long. John D. Fournet, the speaker who had sought to adjourn the House of Representatives during the riot of 1929, was lieutenant governor. They had headed what was known as the Complete-the-Work ticket; with both state and city machines solidly behind them, they polled a majority of something like 56,000 votes. St. Bernard Parish, chafing under the stigma of having counted 9 votes out of 3,988 against Senator Long in 1930, set a new high by tallying exactly 3,152 votes for every candidate on Mr. Long’s Complete-the-Work ticket, and not one single solitary ballot for any one of the 23 opposition candidates.

As always when confronting a new audience, “antics” were expected of Senator Long when he reached Washington, but none developed. Washington began to wonder whether, after all, this stuff about pot likker and green pajamas and “them birds” had been anything more than highly colored publicity. Then Mr. Long took the first step toward what he called “redistribution of our national wealth” by proposing a resolution to limit individual incomes to $1,000,000 a year, and bequests to not more than $5,000,000 to any one child, the balance of all incomes or fortunes in excess of those figures to go to the national treasury. The Democratic leader, Senator Joe Robinson, of Arkansas, rejected the resolution. Then and there Washington learned about Huey Long, for his response was an immediate resignation from all Senate committees, with the explanation that he would take no further assignments or honors from a party leadership he refused any longer to follow.

“I met myself very quickly on the proposition of Robinson for President,” he stated. “Right now I’m for Robinson to be Hoover’s running mate, since they both stand for the same thing.”

But it was a cartoon in the Chicago Tribune, showing Joe Robinson beneath an American flag and Huey Long under the red banner of Communism, which really set off his ire.

That was the prelude to the delivery of the speech which has since been reprinted by the millions, under the title of “The Doom of America’s Dream.” It was the first official utterance in behalf of what is now the Share-the-Wealth program.

The Steam Roller at Work

With the Choctaws and the Long organization still solidly welded, Overton was elected to the Senate, in the primary election, by a vote of 181,464 to 124,935. Broussard and a newly organized Honest Election League — “Every time I beat ’em in a campaign, they go get ’em up a new league!” — attacked the validity of the primary, not on the ground that Broussard could or would have won, but on the allegation that enough corruption had been practiced by the Overton supporters to taint the title of their candidate to a seat in the Senate. There were three public hearings by senatorial subcommittees, and the record of the proceedings covers 3,886 closely printed pages. While condemning such things as Louisiana’s lack of a Corrupt Practices Act and the use of dummy candidates to get control of polling-booth commissioners, the committee refused to unseat Senator Overton.

Flushed with this success, the state and city machine coalition pitched in to put over a series of constitutional amendments at the same election at which Franklin Roosevelt defeated Herbert Hoover for the presidency of the United States. The casual count of votes on these amendments brought on a probe by District Attorney Eugene Stanley, of New Orleans, and ended in the indictment of some 513 polling-booth commissioners, whom the state administration freed from their predicament by a new law which halted all further prosecutions.

Within a month, the city and state organizations broke the entente that had linked them for more than two years. Senator Long demanded that District Attorney Stanley be not endorsed for reelection in the approaching municipal primary. By a vote of 12 to 5, the Choctaw caucus rejected his demand. He immediately put out a city ticket of his own to oppose the regulars and the reform ticket as well, but his slate was soundly trounced and the regulars won.

Voters in Revolt

Prior to this time, however, an even more serious blow had been struck against his prestige in the Sixth Congressional District. Bolivar Kemp, congressman, had died in June, and because of the disaffection of the voters in that region, the Long organization had sought to evade the test of strength there by refusing to call an election to fill the vacancy. In November, a mass meeting of indignant citizens in Baton Rouge called an unofficial primary of their own and announced the winner would be given credentials to represent the district in Congress.

The state administration swung into action at once, through a district Democratic committee on which the Long forces held a majority. After refusing for six months to call an election, Governor Allen now called one for a date only a week hence. On the plea that this allowed no time to hold a primary, the district Democratic committee then arbitrarily named Mrs. Bolivar Kemp, the late congressman’s widow, as Democratic nominee. In Louisiana, Democratic nomination is tantamount to election. Usually, in such a contest as this, there is not even a Republican candidate in the race. Throughout the district citizens went into literal — not figurative — revolt.

“Never before has such a scoundrelly attempt been made to defeat the expression of the people’s will,” wrote Hodding Carter, editor and publisher of the Hammond Daily Courier. “If our stern protest is not answered, let us read our histories again. They will tell us with what weapons we earned the rights of free men. Then, by God’s help, let’s use them.”

In Amite, in St. Francisville, in Denham Springs and other parish seats throughout the district, ballots, tally sheets, and other election paraphernalia were seized by force and publicly burned. In the three parishes of Tangipahoa, St. Helena, and Livingston, District Judge Nat Tycer issued an injunction forbidding the election. Adding that “it’s a poor court that can’t enforce its orders,” he began to swear in and arm deputies, his own 82-year-old father being the first to take the oath. He instructed these deputies to go out and deputize others to help enforce the court’s ruling. A truck that sought to bring election supplies into the district was driven off by gunfire. In Hammond and in Plaquemine, Senator Long was hanged and burned in effigy.

Something less than 5,000 votes were cast for Mrs. Kemp in a district ordinarily polling more than 42,000, although she was the only candidate. Hers was the only name on the ballots. Three times as many votes were cast a fortnight or so later in the citizens’ election, at which J.Y. Sanders Jr. was the only candidate. However, the House of Representatives at Washington refused to recognize either election as valid. A new election was called, close upon the defeat of the Long ticket in New Orleans. Once more J.Y. Sanders Jr. was victorious.

That succession of victories over the redoubtable Huey sent the anti-Long contingent into full cry. Achilles really did have a vulnerable heel apparently. They began to rally their forces and confected a new sort of round robin, a pledge to oust Speaker Allen Ellender when the legislature convened in May, with the idea that this would be followed by removing Fournet, and later, perhaps, by the impeachment of Governor Allen. With the legislative machinery in their hands, the opposition would soon be in control of the state.

Of the 51 signatures needed to show a pledged majority in the House of Representatives, 48 were secured. The fact that the other three could not be gained was due primarily to the personal popularity of Ellender. Once it became definitely known, however, that the Long forces would remain in power, there was a regular stampede from the opposition to the administration. The Long political fortunes swung upward as swiftly as they had plummeted toward the depths. From a position where not more than three legislative votes stood between him and political extinction, Huey Long rose to a more complete absolutism than ever, and the Putsch-Over of 1934–1935 was begun.

From all parts of the state had come a demand for a reduction of automobile-license fees. Very well. The Long forces acceded to that demand, but coupled with it a proviso that would take away from New Orleans and its anti-Long city administration $700,000 a year in highway revenues. In order to reduce their auto taxes, the country members had to deprive New Orleans of this income, which gave them no pause whatever. Similarly, a bill authorizing New Orleans to regulate private boathouses along Bayou St. John was changed by amendment to take away, in addition, all control by the city authorities over the local police force.

A Law Mill in High Gear

At this point the Putsch-Over was abandoned for the time being, because the Long-Allen administration had its own legislative grist to grind in the way of a promised tax-relief program, under whose terms the first $2,000 of the assessed value of all owner-occupied homesteads was to be exempted from property taxes. To make this possible, it was further proposed that the revenue thus lost be made up by levying six new taxes — an income tax, an insurance-premium tax, a tax on stock-exchange and cotton-exchange transfers, a tax on newspaper advertising, and the like — thus shifting a portion of the burden of government from real estate. Much of this legislation required a two-thirds majority. Not until it had been securely consolidated was the real Putsch-Over begun.

Special session followed special session; half a dozen in the space of less than a twelvemonth. No need to mince matters now. Forty or more laws would be shoveled in a few minutes before midnight of the opening day of each session. Without regard to subject matter, all would be referred at once to the ways-and-means committee, where the Long forces had a majority of 15 to 2. Following a consideration which averaged two and a fraction minutes per new law, this committee then reported all administration bills favorably, after which the House would enact them and rush them over to the Senate, where the same procedure was followed. In this fashion, a law was passed giving the state supervision over the appointment of every nonelective employee of every parish, city, or village in Louisiana. In this way a law was passed providing that the governor would henceforth have the right to appoint all polling-booth commissioners in every primary election. Thus the law was passed providing for the appointment of an unlimited number of state police, permitting the governor to call out the militia at pleasure, ousting hostile local administrations, giving a state board control of the appointment of every schoolteacher in Louisiana.

Bills Passed in a Few Seconds

As a matter of cold record, even this procedure was speeded up during one session after the legislature was thoroughly broken to the idea of unquestioning enactment of any bill proposed by the Long administration. Laws were passed with only a few seconds of total consideration, under regular rules of procedure, by doing something no one else had ever thought of doing before. A bill may be amended at any time before the moment of its final passage. Thus an innocuous codification of existing laws would be introduced. After this had been passed by the House, and a moment or two before the Senate was to take final action, the Long floor leader would introduce an “amendment” which was the real new law. In one case such an amendment was 200 pages long and was adopted in less than a minute of elapsed time. It was then rushed to the House for concurrence, and was laid on Governor Allen’s desk for his signature within a matter of minutes after its first appearance in the legislative assembly. In precisely this way the manufacturers’ license tax, which had brought on the impeachment proceedings of 1929, was enacted in 1934; the only difference was that it had now been made more far-reaching, since it no longer applied merely to the refining of petroleum but to every other manufacturing industry except the processing of bread, milk, and ice.

This kindled the flame of revolt once more; not among the members of the legislature but among the employees of the Standard Oil Company, 1,000 of whom were laid off within the week; the great refinery cutting its operation to a minimum as a prelude to shutting down. Along with a number of sympathizers, they finally armed themselves and seized the courthouse at Baton Rouge, which had just been annexed to the Long organization by the simple process of enacting a law authorizing the governor to appoint enough additional police jurors — the Louisiana name for county commissioners — to give the Long side a majority over the elected commissioners. Short shrift was made of this rebellion. Baton Rouge was put under martial law, a number of leaders were charged with conspiring to assassinate Senator Long, and a number of others, who armed themselves and gathered at the Baton Rouge airport for action, were dispersed by militiamen without a single shot being fired save for the discharge of one shotgun, which was not in the hands of a uniformed soldier, but severely wounded one of the revolters. The situation was eased off when the five-cents-a-barrel tax was compromised for one cent a barrel.

Plot and Counterplot

Another “murder plot” was bared in the summer of 1935 by Senator Long, and laid to a group of five anti-Long congressmen, who met in New Orleans several months ago to confect an anti-Long ticket for the approaching state and congressional primaries. Two members of the Long organization moved into the hotel room adjoining that of the congressmen and recorded the conversation through a concealed listening device. Gossip has it that the records thus made were to have been reproduced over the loudspeakers of the Long fleet of sound trucks, during the campaign this winter. The senatorial primary had been moved up from early autumn, the usual date, to January, 1936. Senator Long planned to have his senatorial campaign nicely out of the way before the presidential conventions of next year, with every municipal employee, every state employee, every schoolteacher, and every polling-booth commissioner in Louisiana a part of his state machine; with the militia, the state police, and an unlimited number of special polling-place deputies at his beck and call.

It was just before the past year’s Putsch-Over, which made all this possible by law, that the Share-the-Wealth cycle of Mr. Long’s political history had its inception. The Reverend Gerald Smith had just quit his pastorate in a Shreveport church over differences with his board concerning social liberalisms advocated from the pulpit. Struck by the tenor of Huey Long’s speeches for the redistribution of wealth, he sought out the senator, and the two spent some time together. Doctor Smith was with Mr. Long on the fateful January night in 1934 when the returns of the city election spelled such decisive defeat for the Long municipal ticket. The throng that had milled about campaign headquarters early in the evening, cheering, jostling for a chance to shake hands with Huey Long, melted away as the returns were tabulated. By the time victory for the opposition was conceded, the rooms were almost deserted.

Doctor Smith remained with Huey Long that night, endeavoring to comfort him. He accompanied him to the national capital a day or so later, and, indeed, was mistakenly assumed by Washington reporters to be a new bodyguard. Early one morning, about three o’clock according to some versions of the incident, Huey Long summoned his secretary, Earl Christenberry, and the Reverend Smith to his rooms, and excitedly explained that he had just thought of a national organization, without dues of any sort, to be known as the Share-the-Wealth Society; something to be welded into a national Huey Long political unit on the basis of a platform whose principal plank was the decentralization of fortunes.

A Political Jack-of-All-Trades

He gave Louisiana good roads — miles and miles of them. He succeeded in providing funds for building bridges, equipping hospitals and other eleemosynary institutions, enlarging a university, founding new colleges in conjunction with it, and, in short, putting into physical effect a construction program of vast expenditures at a time of general financial depression. He succeeded in raising the state’s revenues to figures of previously undreamed-of scope by adding new taxes and increasing old ones, but apparently without incurring the hostility of a voting majority of his electorate thereby. His Putsch-Over deprived Louisiana communities of any semblance of local self-government, but in the main he was a benevolent despot to all who acknowledged his autocracy.

And finally, he managed to crystallize about his genius for political evangelism the general feeling of worldwide unrest, the vague discontent evoked by the thought: “Why does the fact that we produce more than ever at less effort than heretofore mean that we must have less to enjoy?” He did this through his Share-the-Wealth movement, whose principal organizer said that this movement consciously deified him to ensure the success of a new economic and social philosophy.

On August 30, 1935, the man who manifested himself on the national stage as a sublimated precinct politician, as a notable Washington personage, and as a nascent apostle was 42 years old.

Less than a month later, he was shot and killed by Dr. Carl A. Weiss, Jr., in one of the ornamental marbled hallways of the lavish state capitol he had built as governor of Louisiana.

Senator Long had just convened another of his amazing special legislative sessions. The New Orleans Choctaws had surrendered at discretion. Money withheld from the city treasury for months was now to be made available. Along with this, bills virtually depriving two anti-Long district judges of places on the bench were tossed into the legislative hopper. One of the judges, gerrymandered into a district where, as a practical matter, he could never have been reelected, was the father of Doctor Weiss’ young wife. Friends and foes alike flout the idea, however, that this could have aroused the studious 30-year-old physician to the pitch of homicidal vengeance.

A Legislative Tribute

By agreement among his supporters, the legislative program of the session he had initiated was carried out “just as if Huey was still here with us,” this being held a deeper tribute of respect and affection than any formal adjournment. The only impromptu feature added to the assembly’s program was the joint resolution authorizing the interment of Huey Long’s body in the spacious grounds of the Capitol his administration had built.

A week after this article was published, the Post published the editorial “The End of a Chapter.” While remarking on Long’s “remarkable qualities of wit and outspokenness, together with rare showmanship” and roundly denouncing political assassination, the editor’s relief that the Share-the-Wealth movement had come to an end is almost palpable.

The End of a Chapter — The Death of Huey P. Long

Shortly after the assassination of Huey P. Long on September 10, 1935, the Post published the editorial “The End of a Chapter.” While it raises up Long’s “wit and outspokenness” and his “rare showmanship,” it openly denounces his radical “Share Our Wealth” campaign, which, sought to put a cap on personal fortunes and provide a base-level homestead for every family.

Learn more about Huey “The Kingfish” Long’s politics, life, and legacy in “Long before Trump: The Unsettling Popularity of Huey Long.”

The End of a Chapter

Editorial

Originally published on October 19, 1935

Men and events have a way of quickly becoming dim memories, but it will be many a day before the American people forget the strange career and colorful personality of Huey Long. He had remarkable qualities of wit and outspokenness, together with rare showmanship. Yet in wide and not unintelligent circles his violent death met with rather perfunctory expressions of regret.

Assassination under any circumstances or for any reason is not to be condoned, but it is the natural result or child of despotism. It has no place in our system of government, but neither has the type of government that was shaping up in Louisiana any place in our system.

Even before Long was killed, it was frequently pointed out that his whole career showed how mere laws do not insure or protect democratic institutions. Even while maintaining its legal and ostensible forms, he pointed the way to their destruction. Once again we are forcibly reminded that each new generation needs to be educated in the values of liberty and self-government, and that our whole political system requires constant revitalization from the bottom up.

Finally, any gifts which come to the people as the result of despotism are paid for with too great a price. Long was at times a searching and relentless critic of the present administration, but the cynical and ruthless way in which he ran his own state detracted from the sincerity of his strictures; no one could be sure of his motives or purposes.

He posed as a great friend of the people and made promises to “share the wealth” so absurd that any but the most gullible should have seen through them. It has never been suggested that the political machine under his personal management was a purely altruistic organization. Public men, like all others, must be judged by actions, not by words.

Huey Long was a friend of the poor and oppressed only to the extent that he led his own state along paths of enlightenment and progress, and within the framework of democratic institutions and self government.

If he did not do this, he was no friend of the people at all, no matter how inflated, exuberant, and grandiloquent his promises of what he would do if elected president. The only leaders in public life who should be listened to and followed are those whose promises square with their past performances and whose speeches are consistent with their actions.

Arnold Palmer Introduces the Grand Slam

In 1960, Arnold Palmer became the first professional golfer to win mote than $75,000 in a single season. More than halfway to this goal in June, the 30-year-old talked with the Post about how he planned to make his mark on the sport.

I Want That Grand Slam

By Arnold Palmer as told to Will Grimsley

Originally published June 18, 1960

Ever since I was able to walk I have been swinging a golf club, and ever since I was big enough to dream I have wanted to be the best golfer who ever lived. At one time I was certain that someday I would duplicate Bob Jones’ “grand slam” of 1930 — that is, sweep the United States Amateur and Open Championships and the British Amateur and Opening a single year. Then I found out — to my disillusionment — that to devote the necessary time to golf, yet still remain an amateur, I would need either tremendous wealth or a high-paying job with no responsibility.

For me, such prospects were as far away as the moon. I concluded that if I were going to reach the top in golf, I would have to do it as a professional. It was then that I started thinking about a professional “grand slam.”

When I got off to such a fast start this year — winning five of my first thirteen tournaments, including my second Masters in three years — I determined to make my bid. Now my sights are fixed on winning the four biggest tournaments open to a pro — the Masters, the U. S. Open, the British Open, and PGA (Professional Golfers Association of America). Ben Hogan won the first three of these in his great year of 1953, but had to pass up the PGA. No golfer ever has taken all four in the same year. The odds against it must be at least 1,000 to 1. Yet I feel confident that, with a little luck, it can be done. I want to be the man to do it.

Many people felt that Hogan’s 1953 achievement was at least equal, and maybe even superior, to Jones’ 1930 sweep because of the keener competition Hogan met. I agree. I believe Bob Jones, a wonderful sportsman, also might agree. In his heyday Jones had to beat only a small handful of top-flight players. In a big tournament today, anywhere from 30 to 40 men are capable of winning. Jones always has acknowledged that in his time it was possible to win a tournament with three good rounds and one bad round, whereas now it generally takes four good rounds to come out ahead. I think one major victory today is worth two in the Jones era.

The next major test for me is the National Open at the Cherry Hills Country Club this week in Denver. From there I go directly to Dublin, Ireland, to team with Sam Snead in the Canada Cup matches at Portmarnock Golf Club next week. These matches should help me get adjusted to the new playing conditions I’ll face in the hundredth anniversary British Open at St. Andrews in Scotland beginning July 4. After that comes the PGA championship, which opens at Akron, Ohio, on July 21.

Frankly, I am very excited about the British Open, whether or not I still have any chance for my grand slam by the time I get there. The United States has had only two British Open winners in the last 26 years — Sam Snead in 1946 and Ben Hogan in 1953. Our top golfers seldom compete in this championship; they don’t like to leave the rich American tour for an event which offers a first prize of only about $3,500. I’ll miss tournaments worth about $100,000, but I don’t care. I got into this business primarily to win championships. Money is important to me, certainly, but mainly as a means to an end. The money helps make it possible for me to go after the big titles, and I won’t be happy until I win them all.

If I miss out on a slam this year, I intend to keep trying. I am 30 years old — five years younger than Hogan was when he won the first of his four National Opens — and fortunately I am healthy and strong. I believe I have at least 10 more good years of tournament golf ahead of me. Pap — my father, Milfred Palmer, who taught me almost everything I know about golf — insists I’ll be playing competitively until I’m 50.

“The main thing is to take care of yourself, boy,” he keeps telling me. “A man’s body is like a tractor. Keep it in shape, and it will be serviceable for years.”

I seem to play my best in the big tournaments. For one thing, my game is better adapted to the tougher courses. For another, I can get myself more keyed up when an important title is at stake. I like competition — the more rugged the better. When I get on a hard, exacting course, I feel as if I’m wrestling a bear.

Such a course is the Augusta National, where the Masters is played every year. It’s a course that will snap back at you — even swallow you — when you least expect it. I won there in 1958, then kicked away the 1959 tournament on the final round by taking a six on the par-three 12th hole and missing putts on the 7th and 18th. Art Wall Jr., who birdied five of the last six holes, beat me out by two strokes.

Because of that 1959 disappointment, I went to the Masters this year more determined than for any other tournament I can remember. I passed up the Azalea Open at Wilmington, North Carolina, in order to arrive at Augusta a week in advance. I think I startled Mrs. Helen Harris at the registration desk when I checked in.

“Well, this is my 13th tournament of the year,” I told her. “Why don’t you enroll me as number 13?”

Mrs. Harris did — a bit reluctantly. So, my caddie, Nathaniel Avery, better known as Iron Man, had to wear a big 13 on his back all week. He didn’t like it, but he stuck it out; he has been my caddie there for six years.

I found myself installed as the six-to-one betting favorite for the tournament. Masters tradition has it that the advance favorite seldom wins. Newspapermen kept asking me how it felt to be put on the spot as the man to beat.

“It doesn’t bother me,” I told them. “What the bookies and sports writers say doesn’t affect the way the ball bounces. I never think of such things.”

It looked for a while as if my defiance of superstition might backfire. On the Sunday before the tournament I caught a flu bug and was miserable. I didn’t practice at all on Monday. I got a shot in my hip and stayed in bed the entire day. On Tuesday I played 14 holes. On Wednesday, the day before the opening round, I played only four.

However, when I went to the first tee on Thursday, I felt fresh and eager. I shot a five-under-par 67, with an 18-foot putt on the final hole, and led by two strokes. I putted poorly the next day for a 73, but stayed ahead by a stroke. In the third round, I shot a 72. That sent me into the last round with a one-stroke edge over five tough professionals — Ben Hogan, Ken Venturi, Dow Finsterwald, Bill Casper, and Julius Boros. I now had a chance to equal the 1941 feat of Craig Wood — the only man in the previous 23 Masters tournaments to lead every round.

The final round quickly developed into a three-way battle among Venturi, Finsterwald, and myself. Venturi andFinsterwald, playing four holes ahead, both had two strokes on me at one stage. I was on the 14th hole when Venturi finished with a fine 70 for a score of 283. Finsterwald missed a tricky eight-foot putt and wound up at 284.

In our business they say it’s best to be in the clubhouse with a good score — as Venturi was — and make the guys on the course come and get you. I needed to play those last four holes in one under par to tie, and two under par to win.

The best I could do at the long 15th hole and the short 16th was to stay even with par. As I moved on to No. 17, Winnie, my wife, came out and put her arm around my shoulders. “You’re doing fine, honey,” she said consolingly. Pap, who had come down Saturday from our home in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, gave me a wink and a sign as if to say, “Go get ’em, son.” Iron Man, my caddie, was almost in a state of shock. He fumbled nervously with the clubs, and every time he tried to say something, the words clogged up in his throat.

As for me, I wasn’t nervous. I was keyed up, of course, but the juices in my system were flowing normally. I read later that Venturi said he played the final round without once looking at the scoreboard or checking on what I was doing. With me it was just the opposite. I got reports at every hole. I knew exactly what I had to do. I was confident I could get at least one birdie on the final two holes to tie him — somehow, I always feel I can get a birdie when I need it.

The 17th is a par-four hole of 400 yards. I hit a good drive, but my eight-iron approach sat down too quickly and left me well below the cup — about 30 feet away from it, I would say. I remembered that the year before, on this same hole in the final round, I had missed an easy three-foot putt because I failed to read a slight break to the left. This putt, although much longer, was on virtually the same line. So I struck it boldly, intending that if the ball stayed up, it should break a little left at the hole. It did. It plopped into the cup for a birdie, and half my job was done.

There was high tension and wild excitement all around me at the 18th tee. The only sensation I felt was that my mouth was awfully dry. I would have given 10 bucks for a sip of water. But my main interest was in getting my drive on the fairway so I could be reasonably sure of my par. Par on the 18th is four. The hole is 420 yards and uphill, and we were playing into the wind.

My drive was a good one, a bit to the right. Then I punched a six-iron to the green about six feet to the left of the pin. Again I remembered the last day in 1959. I had had a ball in almost this exact spot. I had become disconcerted by the whirring of newsreel cameras and missed. This time I intended to take no chances. I studied the putt very carefully. I asked the newsreel men to stop their cameras. I gave the ball a solid whack. It dropped. That was the tournament.

“How did you do it?” one friend asked me later. “I would have swallowed my Adam’s apple.” Another said, “With that putt on the 18th, I don’t think I could have brought my putter’s blade back.”

Well, I don’t think I have any stronger nerves than the next man. I suspect it’s just the patience I got from my mother and the ornery bullheadedness I inherited from Pap. My mother and father are of stolid German-Irish stock. Both their families settled in the hilly section east of Pittsburgh in the early 1800s and have been there ever since. Originally they were farmers and landowners. Later some of them, such as my dad, drifted into the steel mills and other lines of work.

Pap never had it easy. When he was just a tyke, shortly after he had learned to walk, he came down with polio and was in bed for months. Then he had to be taught to walk again. Today his left leg is about one-fourth as big around as his right, and he walks with a distinct limp. But he developed into a par golfer. He can chin himself with either arm, and 30 times with both. He swims like a fish.

Pap has served at the Latrobe Country Club in various capacities for 39 years. He first worked there as an ordinary laborer when this nine-hole course was carved out of a mountainside. He helped put the roof on the clubhouse. Later he became greenskeeper and took some courses at Penn State to learn more about grass. Then in 1933, in the midst of the depression, he was made combination greenskeeper and pro at the club at a very modest salary. To keep his growing family in groceries, he had to work in the steel mills during the winter.

Latrobe is an industrial community of about 15,000. It is about 30 miles east of Pittsburgh, off U.S. Highway 30. Three independent steel mills provide most of the employment. There also are some thriving construction businesses. The golf course is now in the process of expanding from nine holes to eighteen.

My family has always lived within a brassie shot of the course. I am the oldest child, born September 10, 1929. I have a married sister, Mrs. Ronald Tilley, 28, living in Washington, D.C.; a brother, Milfred Jr., better known as “Jerry,” 15, and a kid sister, Sandy, 12. None of them is very interested in golf.

I couldn’t have been more than three when I got my first golf club. It was an old iron with a sawed-off shaft. The first thing Pap showed me was the proper grip — the Vardon overlapping grip. I vividly remember swinging the club hours at a time as Pap and his men worked nearby. I’d be swinging at some remote spot on the course, and my dad would walk by and tell me what I was doing wrong. I would correct myself and start swinging some more.

Pap says that’s the reason I have such big hands. “They’re the hands of a blacksmith or a timber cutter,” he says. “You can only get hands like that by swinging an ax or a golf club.”

My father always impressed on me the importance of keeping a firm hold on the club and not letting my swing get too loose. Even as a kid I kept my swing compact. I tried to hit the ball so hard I often would lose my balance.

“Deke is ruining that boy,” some of the club members would say. “He should make the kid swing easy.” Pap, who doesn’t know where he got his nickname of “Deacon,” or “Deke,” never let this criticism bother him. “It’ll work out all right as you get older,” he told me. He was correct.

Although my dad was the club pro, I didn’t have free run of the course. On the contrary, the club maintained the old British aloofness toward professionals and other employees. I wasn’t permitted on the course except on Mondays, when it was closed to members.