Rockwell Video Minute: Road Block

A lot of detail goes into every Rockwell painting. In this video, we break down how he turned a boring alley into a hilarious scene teeming with many characters and one great story.

See all of the videos in our Rockwell Video Minute series at www.saturdayeveningpost/rockwell-video.

North Country Girl: Chapter 41 — The Playboy from Chicago

I had made my mad escape from Minnesota winter and flown back to Acapulco, where I knew exactly two people, one of whom I was pretty sure hated me.

I took a cab to the other one’s apartment. I had no way of letting Jorge know I was coming, so I sat on my rock-hard suitcase for hours in the shaded passage way outside his apartment waiting for him to show up. I wondered where I would be working; at everyplace I had been, from the pool at the El Presidente to Armando’s disco, the wait staff had been exclusively male.

I was nodding off when I heard “Gay?” followed by a string of Spanish and then a halting “What are you doing here?” It had never occurred to me that Jorge might not be happy to see the silly tourist girl who had publicly jilted his best friend and boss. He sighed and let me into his studio apartment, where every surface was covered with clothes or empty Corona bottles. I tried to look adorable.

“Jorge, remember, you told Mindy you could get her a job here—you could get me one too, right?”

Jorge looked frantically around the room as if there were a job there I could have, and sputtered he guessed so, maybe in a couple of days. Where was I staying?

“Why, right here with you.” I had planned on crashing at Jorge’s till I found a place. Jorge looked even more alarmed and squawked out that he knew somewhere I could move into immediately. I was lucky he didn’t toss me and my Samsonite out and slam the door, leaving me to figure out by myself how to start my new life in Acapulco.

We cabbed across town to an apartment occupied by a passel of pretty French Canadian girls who had come to Acapulco in search of rich Mexican men, with marriage being the elusive, ultimate goal. (I have just this moment realized I should have introduced them to Baldy.) Four of them had set off together from Montreal, but one had given up and gone back home, so the girls had a vacancy in their one-bedroom apartment. Jorge introduced me, dropped my suitcases on the floor, and took off, as eager to leave me as I had been to dump his pal Fito a few weeks before.

These gorgeous creatures and I managed to communicate in a blend of French, Canadian French, Spanish, and English, as they showed me around. I pointed at the one and only bed and asked in three languages and using my fingers, “One? Four?” The girls gave a communal Gallic shrug and explained that on the rare nights any of them came home, they just shared the double bed. Ça ne fait rien, so far the most there had been was three girls in the bed at one time. I was a bit taken aback by this informal arrangement, but I liked these pretty, honest gold diggers, I loved the apartment, and I had no other choice. I found a space to put my bags and fell into that bed exhausted. I spent the night alone without the company of single beautiful French Canadian girl. The three girls showed up at various times the next day to drink coffee, plot their next conquests, and catch up on their sleep, rotating in and out of the bed.

It was a sweet little tropical apartment, perched on a hill a few blocks up from the beach. Only the bedroom was enclosed; the rest of the apartment was open to the salt-tinged breezes. A huge shady patio was surrounded with palm trees and bougainvillea and hibiscus. There was tiny kitchen off to the side, the only appliances were a dorm-size fridge holding nothing but agua con gas and a can of Nido powdered milk, and a hot plate where the girls boiled water for the morning cafe au laits. We weren’t high up enough to see the ocean, but the luxuriant foliage blocked our view of the dusty street below, and we were a cheap taxi ride away from Carlos’N Charlie’s. The girls refused to travel anywhere on foot.

The French Canadian girls spent their time at the apartment changing clothes, reapplying makeup, napping, reporting back on where their dates had taken them, and discussing their marital prospects. The pool of eligible men they swam in was a band of wealthy young Mexicans who could be counted on to pick up the check. It’s too bad none of the girls had read Breakfast at Tiffany’s and so missed out on asking their dates for $50 for the powder room. It would have helped pay the rent, but might also have meant they wouldn’t need the fourth roommate: me.

Not surprisingly, I never heard back from Jorge about a job.

A few days after I moved in with the French Canadians, they invited me along as a spare girl (can’t have too many of those) to spend the day at a private beach club. One of the girls’ main criteria for their dates was membership at Le Club.

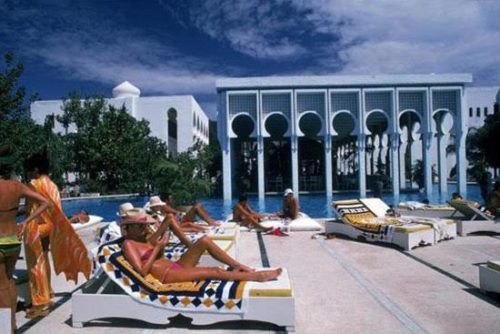

My foolish, glamorous nights at Armando’s disco did not prepare me for the wonder of Le Club; most of the world still pales in comparison. It was as if Disney had decided to redo the Taj Mahal, only making it even more luxurious and for adults only. Huge gleaming white domed buildings, as pristine as one of Fito’s shirts, soaring decorative arches that held up nothing but themselves, ornate fountains with demented dolphins or nymphs spouting rainbows of spray twenty feet in the air, in the center a pool lined with tiles the color of lapis lazuli, a pool that went beyond Olympic to cosmic-sized. Everything was blue and white, coordinating perfectly with the sky, the sea, and the strip of white sand visible over the beach wall. The only other color came from tan girls in bright bikinis. Le Club looked out majestically over the Pacific, turning its back to those unfortunates without money or looks. If it hadn’t been so breathtakingly beautiful, it would have been the worst kind of trashy kitsch.

Escorted by six young Mexican men, who had both the looks and the money, we strolled into Le Club as if we owned the joint. I tried to copy the French Canadians semi-bored sang froid, I tried to be cool. But it was no use. I gasped at the sight of that gorgeous, totally empty pool, dropped my bag and cover up on a lounge chair, and dove in. By the time I had swum one block-long length and back, an army of waiters was arrayed around our group, setting up umbrellas, ice buckets, and tables, and popping corks from champagne bottles. Before I had finished my first glass of champagne, more waiters were bringing beers and margaritas, club sandwiches, shrimp cocktails, French fries, and cheeseburgers. “Gracias! Gracias! Gracias!” I squealed to the waiters as they set down plate after plate of delicious free food. At Le Club I never saw a menu or folding money; the waiters knew the members’ regular orders and everything went on a tab. My French Canadian girls had unerring instincts and I hope they all married well.

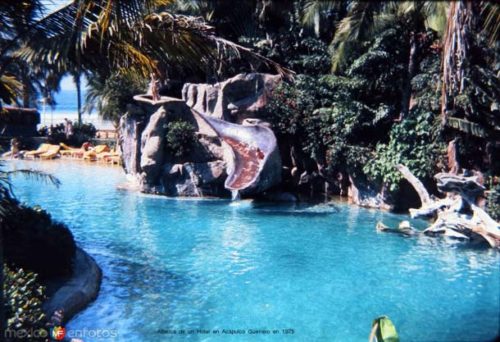

The narrow white-painted iron gate in the beach wall was always locked; no one ever went to the beach at the beach club. The pool at Le Club made the one at the El Presidente hotel look like the Y. It had different sections, one for doing long languid laps, one with a little waterfall and grotto, and a large area surrounded by lounge chairs and umbrella tables where we had set up, drinking and eating the afternoon away. The French Canadian girls, who had spent hours on their makeup and hair, cooled off by sitting on the edge of the pool, kicking their long golden legs in the water, and looking delectable. My mascara and lipstick were long gone, and I was never able to do anything with my hair anyway, so I jumped back in the water and frolicked with the cute young Mexican men. I made it a point not to focus on any one of them, as I did not want to catch the eye of a potential husband and risk being tossed out of the apartment by a jealous French Canadian.

After several bottles of champagne had been turned upside down in the ice buckets (and quickly replaced with new ones), the men decided that we should have luchas de pollo. I hung back for a minute, the man who was gesturing for me to climb up his back and sit on his shoulders might already have been claimed. The French Canadian girls gave a collective sigh, gingerly lowered themselves into the pool, and made their way to their selected suitors. I choose one of the leftover men to mount for the chicken fight.

Being a bit tipsy on champagne while riding on the shoulders of a rich young Mexican guy in a private pool was exactly why I had left Minnesota. And I’m sure the sight of four pretty young women, wet and in bikinis, pushing and shoving each other was excellent entertainment for the rest of Le Club’s clientele, well worth the price of membership.

We played in the water until we were parched from laughing and chlorine. At the suggestion of a champagne break we pulled ourselves out of the pool and into our lounge chairs; attendants hurried over with soft, fluffy towels as waiters hovered with freshly uncorked bottles. The French Canadian girls fell into deep conversations with their potential fiancés, trying to get them to order more sandwiches, firm up dinner plans for that night, or consider shopping for rings.

“You looked like you were having fun out there,” said an American voice, a voice with a deep, husky purr. The voice came from a man who was tanned to a deep brown, like a well-roasted turkey, with a Burt Reynolds mustache and a thick head of black hair. (I later discovered he was as proud of his hair as if he had cultivated it himself on a plot of land.) His face was vulpine, almost devilish, with deep-set brown eyes. Of course he sported a heavy gold chain around his neck. I may have seen thinner men, but never wearing swimming trunks that revealed not an ounce of excess fat. Looking at him I regretted every handful of beer nuts I had ever guzzled while in sundae hell at Pracna.

I laughed and confirmed that yes, I was having great fun. “Which guy are you with?” he wanted to know, tilting his chin towards the group.

“None of them. I’m just here with my friends.” His smile widened, his eyes opened up a bit more and grew darker.

“My name’s James Rodgers.” He plopped down uninvited on my lounge chair a bit too close for having just met and both of us being mostly naked. I told him my name and it was off to the races.

James lived in Chicago, but he spent every winter in Acapulco. At one time he had been a Cadillac salesman, but now he had investments and didn’t have to go to a job everyday. I didn’t ask how old he was. (He was 42.)

James wondered, “Have you been to Armando’s yet?”

Of course I had. I was surprised he hadn’t noticed me on Fito’s arm; later I realized James had a radar that was calibrated to locate only the single girls in a bar or restaurant; his eyes would have skipped over me and locked on to a tourist girl who wasn’t already claimed.

“Would you like to go to dinner and then dancing?” he asked. Dinner on someone else’s dime was a great idea. As no job had materialized for me, I knew I would not be adding, only subtracting, from my bankroll. I would have let the Hunchback of Notre Dame buy me a steak.

A few hours later, under the approving eyes of the French Canadians, James picked me up in an open-roofed red Jeep. We drove high up into the hills, to Coyuca 22, a restaurant perched on the very top, with a National Geographic view of Acapulco Bay. This place looked like a set from one of those movies where the main character is accidentally sent to heaven, everything gleaming white and oversized. The main decorative feature of the restaurant was a ridiculously huge array of columns that towered thirty feet in the air, fighting for attention with the sparkling city lights reflected in the ocean below and the thousands of stars that spangled the inky firmament above.

That night James introduced me to Mouton Cadet Bordeaux, the first wine I ever had that was not fruit-flavored; Steak Diane, which our waiter brought to our table, poured brandy over, and set on fire; and the forgotten practice of giving ladies menus without prices. (James ordered for both of us anyway.) Once again, the universe was reassuring me that the rash decision to escape from my life in Minnesota had been the right one. James was not as handsome as Fito or Javier, and he was old; but he had more conversation than either of them, and I was an empty vessel, eager to soak up new experiences, new foods, new drinks.

Dinner was over and I had to face Armando’s. I knew that James would shudder in horror if I suggested we go to a lesser disco, such as Le Dome. I had come to Acapulco to be a fun party girl; I had to go to Armando’s and face Fito eventually. Better to be seen with an attractive man, even an old one, than with my gold-digging amies, who wouldn’t have been caught dead going there without a date anyway, in case they might be forced to pay for their own drinks.

Just like Fito used to do, James handed the keys to the jeep to a waiting valet and herded me to the front of the long, snaking line of hopefuls waiting to be allowed in, where he slipped the doorman a folded up bill. Once inside, the host led us to the only open table, as far from the dance floor as possible, smashed in next to the wall. James leaned close and brushed his lips against my face, “What do you want to drink?” I had been hoping a champagne bucket would appear. The pulsating roar of “Love Train” forced me to yell ladylike into his ear that I’d like a gimlet. If I couldn’t pose with a champagne coupe, then I wanted an elegant martini glass for an accessory, something that would establish me as the sophisticated habitué of Armando’s I imagined I was.

I had barely swallowed the first puckery sip of my cocktail when James dragged me down to the dance floor. I guess he really had never spotted me there before or he would have not invited me to show off my Minneapolis Shuffle. James was all Chicago Hustle, twisting his narrow hips, snapping his fingers, and trying to make me look good before giving it up as a hopeless case. He watched me do my own made up, ecstatic, goofy dance moves with a knowing smirk.

We drank, we danced, we drank, we danced, until I was quite drunk with success, with happiness, and with gin. Then I spotted my Canadian girls and right behind them, Fito, Jorge, and their cute dates. I swallowed, stood up and waved madly at the Canadians, one hand firmly on James shoulder, willing Fito to look over and see me with yet another good-looking guy. My luck held: Fito and I locked eyes for a millisecond, before he turned away and buried his face in his new blonde’s neck.

Without as much as an “excuse me” I hopped up and made my way over to my roommates’ table. I finally had something to report: Steak Diane, French wine, big ass columns, all paid for by a rich guy. Because the music was so deafening, it took a while for them to share the details of their dates and whether any progress had been made toward that big altar in the Mexico City Cathedral. I cut my eyes over to Fito’s table, where he sat smooching his newest girl. I guess Fito and I could call it a draw.

When I finally got back to James several lengthy disco songs later, he had a bunch of empty glasses on the table in front of him. Somehow in spite of the pounding music I heard him clearly say, “A lady does not do that to her date,” and I knew he was right. He still let me go home with him.

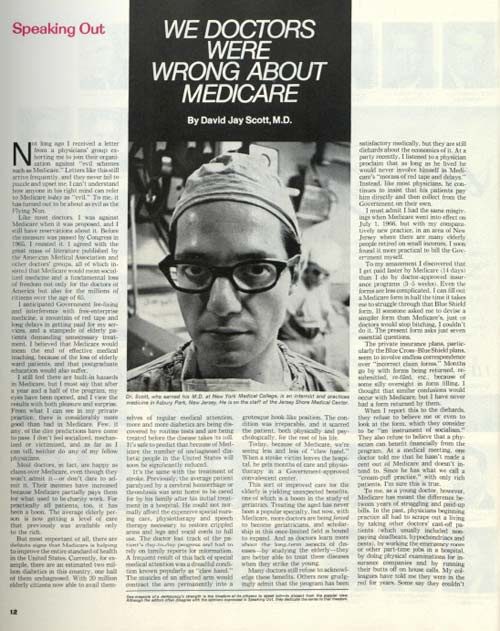

Con Watch: A Dangerous New Twist to Income Tax Identity Theft

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

For years, income tax identity theft has followed a familiar pattern. Criminals use the stolen Social Security numbers of their victims to electronically file phony income tax returns with counterfeit W-2s and obtain a large refund. This scam will only work if the thief files a tax return before the legitimate taxpayer does so. This scam has cost the government billions of dollars each year.

Recently, through the joint efforts of the IRS, state tax officials, private sector tax preparers, and software companies, the IRS has succeeded in decreasing this type of income tax identity theft.

A New Tax Scam

However, the IRS is now issuing warnings about a new, ingenious mode of income tax identity theft being seen for the first time this tax season. The new model starts with phishing emails sent to accounting firms and tax preparers. Phishing emails are emails containing malware-infected links that lure the recipient into clicking on the link. The link then downloads keystroke-logging malware that enables the cybercriminal to gain access to all of the files of tax preparers, including past income tax returns of their clients. These phishing emails often appear quite legitimate and may be directed to the recipient specifically by name. They also are cleverly written to arouse the curiosity or trust of the recipient sufficiently to entice them into clicking on the malware-infected link. Cybercriminals with a knowledge of psychology that Freud would have envied are very adept at crafting successful emails. A recent study by software security company Kaspersky Lab found that the two most popular terms used in recent phishing emails have been “Bitcoin” and “FIFA.”

The cybercriminals then use the information on the clients’ income tax returns to prepare phony tax returns. Because the thieves include much of the legitimate information from past returns, these phony documents are less likely to be detected as bogus by the security software programs used by the IRS to detect identity theft.

But now comes the brilliant part.

The thief directs the IRS to send the bogus refund either electronically to the victim’s bank account or by check. Shortly thereafter, the victim receives a telephone call purportedly from the IRS or a collection agency on behalf of the IRS informing the taxpayer that an error was made and demands that the tax refund be wired back to the IRS immediately or there will be serious repercussions. The call may appear on the victim’s Caller ID as coming from the IRS, however this is easy to accomplish through a technique called spoofing. What makes the call appear truly legitimate is the fact that the caller is able to tell the victim the exact amount of the bogus refund.

The key to avoiding becoming a victim of this scam is to remember that the IRS does not call taxpayers demanding repayments of funds that may have been sent erroneously, and they never demand that tax payments be wired.

What to Do If You’ve Received a Fake Refund

So what do you do if you have already had funds electronically deposited into your bank account by the IRS as a result of this scam? In that event, you should contact the Automated Clearing House (ACH) department of your bank where the refund was sent and instruct them to return the funds to the IRS. Then call the IRS at 1-800-829-1040 to inform them what has happened and to alert them to the fact that you are returning the funds sent to you.

If the refund was sent to you by way of a paper check, you should write “Void” in the endorsement section on the back of the check and return the check to the IRS along with an explanation of what has happened. Indicate in your explanation that you are returning an erroneous refund check related to an income tax return that you did not file. If you have already deposited the check, you should call the IRS at 1-800-829-1040 and explain the situation. They will give you instructions as to what steps to take to return the payment.

“Memoir of a Long, Long War” by Kenneth B. Platnick

Sometimes I’d just lean back against the edge of the broken chair in which I was seated and watch her standing there in La Petite Maison in Saigon alternately laughing loudly and pouting with a mock look of disappointment. Of course, I wasn’t alone in my attentions, but I was certainly apart.

Even the bartender, Tam, a small, nervous man in his fifties with a lock of graying hair bending over his narrow, wrinkled forehead, moved to the farther end of his short and dampened counter to be included in the admiring circle of acquaintances. It was never a large cluster, but it was a perpetual one, with only the individual faces changing occasionally.

She would stand among the tables, resting her ample posterior now and then against one or another of the surface edges, and exchange all the newest local gossip and off-color jokes with the men about her. Invariably, it seemed, whenever one of the more enjoyable stories neared its climax, someone would shout out an order to Tam, and the unhappy little bartender would go scampering back to his regular post to prepare the particular bit of refreshment in demand.

After a while the girl, too, would sit, sometimes on the top of a table, her legs crossed, and her tight dress caught around her knees, sometimes on one of the several chairs that stood unused near the tables. She did not, however, often take advantage of the formal seating arrangements, perhaps because she sought to maintain the only-a-minute-longer posture that kept the others all the more anxious. But when she did, it was a truly grand production. She would pull hard on the end of her skirt with the thumb and two fingers of each hand until she had seated herself snugly against the back of the chair. Then, having made her overtures to modesty and propriety, she would raise her legs to rest atop one of the tables, preferably with her feet barely brushing against someone’s face, and her back to as many others as possible. As soon as she’d chosen her victim for the sport, she would begin twisting her right foot in a clockwise ellipse, pretending not to notice this “automatic” gesture, just to see how long it would be before the officer across the table would raise his face and hurry it back in retreat. (Occasionally, in one of her still-gayer moods, she would manage to kick off her shoes beforehand.) The victim would smile painfully, and all the other men would laugh at his surrender without seeming to realize that they, too, had given in by moving their own chairs around to face the dark Asian beauty.

All this I observed from my dimly lit corner of the room, occasionally ordering another drink when all their laughter had subsided, thus causing her to turn her head slightly toward me. It wasn’t so much a look of reproach as one of curiosity, even puzzlement, that I, presumably a normal and stimulable young man, should impose upon myself exclusion from the fun-and-games circle of which she was the charming and surely stimulating center. I would nod politely back to her, adding a thin, tired smile of thanks for her unspoken, but nonetheless apparently issued, invitation. Then Tam would bring my drink, and I would go on watching. It beat working.

Outside there was always the dull ache of a terrible excitement, everyone wondering where the next big blow would come and just how much longer the fighting could possibly go on. Older women had forgotten what it was like to endure peace, their husbands and sons at their sides, the streets filled only with their compatriots, the sounds of the jungle replacing the sounds of jungle warfare as they slept; young children had never known. The past was like a world that never was, something only faintly remembered, the way one remembers a tale told years ago — and, of course, the ending is past recall. Thousands upon thousands of French soldiers longed to go home, to win this ugly mess of a war and return to the families they had either left or planned. Meanwhile, they would curse the hot sun and filthy marshes and deceptive shrubbery where any attacker could lie in easy wait. They would hate these dirty little people whom they were sent to defend but who cared little for defending themselves. They would taste their homemade white wine and long to hold the bottle; touch the pretty girl with the soft, red mouth and long to feel her breath; smell the brandy-polished crêpes in a Paris café and long to taste their sweetness. It was all so long ago.

But that was far outside, beyond the barely open door.

From my corner, one late Thursday of my remembrance, it began to look just a bit less awful. My story had been filed — after a hot, sticky and seemingly interminable wait at the cable office — and, unless something big broke soon, I was through working for the day. I could afford to sit quietly, and sip my watered drink, and watch.

I had never understood exactly why they called her La Bleue. For some reason, however, it did fit her admirably. Every movement of her lithe body, every decibel of her coarse laugh seemed to betray a sense of loneliness and endless, though quite vain, searching. Running my fingers along the rim of a wet glass, so as to produce a soft, high-pitched whirring sound, I considered at length the inner workings of the girl before me.

And it occurred to me that I knew her by no other name than that of her ambiguous title, which would hardly have served as a form of chance address. I worked awhile on that, certain after my fourth drink that she was nothing she would seem to be and was thus unfit for any name that might sound otherwise suitable.

I called her Charlie. Suddenly, without a hint of warning even to myself, I called her Charlie. When she got up from her chair and walked slowly across the dusty floor to size me up at closer range, I rose half out of my seat and greeted her knowingly.

“Why do you call me that?” she asked in a rough, but not really broken, French.

“Why?” I replied. “What is your name?”

She paused for a moment, presumably in meditation, meanwhile getting herself comfortably situated on the torn cushion of the chair on which she had placed herself in rather elaborate fashion. She glanced about at the uninhabited spaces of the room, then brought her focus sharply back to me.

“Charlie,” she said effortlessly. She repeated it twice more, as though to get the true sense of it, then admitted with obvious pleasure, “Why, yes, it’s a lovely name. It feels so nice on me.”

Tam had come from behind his chest-high barrier to bring her unfinished drink to her. He bumped into the table next to mine on his hurried way. Excusing himself two or three times for the accident, he nervously dropped the glass onto the table, spilling a few droplets and offering again the same profuse apologies for his clumsiness. The girl looked at him with what I took to be something of a cross between outright boredom and utter contempt, and he went running back with the look of a scorned puppy.

“Silly man, is he not?” she asked without caring at all for an answer. “I wouldn’t come here, except that I feel so sorry for him. And I am good for his business, you know. If I ever deserted him, every French officer in Saigon would quit coming here just like that.” She clicked her thumb and third finger together. “Don’t you think I’m pretty, not a little bit?”

I had every intention of assuring her that I found her most attractive, but she had already taken that much for granted. “Then why,” she went on, “do you never join me at my table?”

Certainly, I realized, I could not explain to her my preference for disengaged viewing while she acted out her role. Consequently, I had no answer at all for the unexpected question.

“Yes?” she asked again, then quickly backed off. “Oh, never mind. It’s probably that you’re just shy. Big ears, you know. They say that men with big ears can be awfully shy. But they’re cute, big ears, so you shouldn’t really be.”

I was so taken by surprise with this shameless unmasking that I emitted a short but deep and clearly audible laugh.

“There,” she said, “that’s much better. Now what would you like to buy me to drink?”

“What would you like?” I asked her.

“Oh, it makes no difference. Tam makes them all so bad, you know. But I like to help his business, so you just pick one for me.”

I motioned to the little bartender and sent him rushing back to fetch an arbitrary selection from among his offering. When he returned, drink in hand, he was exceptionally careful to avoid that same adjacent table; and he set the glass down with great deliberation, easily. Then, that feat accomplished, he went back to his own station with the satisfaction of graceful maneuvering.

“Do you like it here?” she asked, explaining further, “I suppose I really mean, how much do you despise it?” She allowed no time for any reply, but traveled on in her verbal wanderings. “You know, it’s a funny thing, but men like you always come out here expecting all kinds of excitement and … ah, the romance of war, the virility of combat, the intrigue of bullet-pierced politics.” She had deepened her voice to heighten the dramatic sarcasm of her rhetoric. “But it only takes a few weeks or months for the glamour to wear off, eh? Then you begin to get moody and melancholy, even bitter a little bit. Trouble is, you don’t ever stay long enough to get like the rest of us, resigned to it, I mean. You too, no?”

I began thinking how close she had come. After six months, there was little enough of the glamour left. When I went home, everyone would be duly impressed with the tales of my exploits, to be sure. But I was living them now, and I hadn’t yet had time to recapture the romantic beauty I had ascribed to them at the outset of my assignment. I began thinking, too, of how my slim period of involvement compared with the years she and her countrymen had lost in the struggle. Could one ever really come to be reconciled with the agonies of those years of terror, as she had indicated? Perhaps. It would not be for me to know, since mine was only a tour of limited duty.

“But this is such depressing talk. Let us speak of more pleasant things,” she offered generously, reinstating for my uplift that wide smile which almost parted her deep red, fleshy lips.

Quickly, scarcely aware of it myself, I cast a curious glance at the small group of uniformed men with whom she had been mingling just a moment earlier. They were still as she had left them, looking a little more serious as they spoke but speaking quite a lot nevertheless, continuing their alcoholic intermission from the martial drama of the outside world, joking still as they had been, going on as if they entertained not a single lack — although each of them undoubtedly wanted dearly to have La Bleue return to keep him company in her diverting and delightfully feminine way. She was surely missed but never recalled; for to recall, even if possible, would have been to spoil the charm.

“For instance,” she went on, “let us speak of you. Are you married, by the way?”

“No.”

“Oooh, that is too bad. I mean, it is good for a man to have someone to think of going home to, no?”

I lifted my shoulders into a slight shrug.

“Indeed, yes,” she explained. “A man, he goes away to another country, and he does not know exactly when he will come home again, or even if he will, and he needs the memory of a good woman who will be waiting for him all the while. Are you not lonely?”

It was such a simple question after she’d spoken it aloud; and yet it was the very one I’d always seemed myself to miss, or from which I’d shrunk, the single question needed to arrange neatly all the miscellaneous and misplaced answers I had accumulated over the longest short period of my life. That was precisely what I was, lonely. Funny how you can feel an emotion so deeply, any emotion but particularly one of a more melancholy flavor, and never come to recognize it for what it is until you no longer possess it, but it possesses you instead. Lonely. Yes, that’s just what I was, above all else in the world; no more the bitterness I had felt or the cynicism I had professed or the realism in which I had cloaked them both. Only the most natural sentiment of all; it was mine to endure.

In an absurdly sudden way, I began to feel deeply sorry for myself. Then, almost before I had got used to it, my cozy mood of self-indulgence was intruded upon, and I heard her speaking to me again. There had, I knew, been only a moment’s pause.

“Yes, of course, you are lonely. How stupid of me to mention it. Tell me about your work instead. It must be so exciting, being a war correspondent and all that.”

I replied with a vague gesture which, however polite, refused to commit me to an opinion of my work. It was, after all, my work, such as I had chosen. Choosing it was itself my final commitment.

“Look, I’ll tell you what. Why don’t you come round to my place this evening? I do have to go now, but I want to talk with you some more. You’re so … well, I like talking with you. You come over tonight. You know where it is, don’t you? My place, I mean. Everyone does.”

“But …” By the time I had managed to express even that single sound, she had risen, patting my shoulder lightly, and turned her back to walk away. She glanced behind her.

“But,” I continued stubbornly, “everyone also knows that your evenings are usually taken. Are you quite sure…?”

“Of course, silly. Do you perhaps think I don’t run my own life? And in my own home especially? You just be a sweet thing and visit with me, eh. I enjoy your company ever so …” and her voice trailed away as she resumed walking briskly toward the door. She waved to the others on her way out, extending only the forefinger of her right hand and the one next to it.

And at once I felt very alone. A buzzing sound again made itself heard, as the party nearby resumed the hum of its own conversation; and I went back to my cupful of now dull warmth, trying to decide quietly — rationally — how I should spend my evening after all.

The colonel, of course, was foremost in my mind. It was he who had set up La Bleue in the comparative comfort which she currently enjoyed, and it was he who regularly commanded the flow of her nocturnal attentions. It was he who, in one rage of jealousy particularly notable for its theatrical absurdity, had promised instant death to any man who might dare to tread upon the sacred ground of his preserve. Monsieur Marais. Monsieur le colonel. Loyalty was to him supreme; he demanded it of his troops and would not suffer the traitor to whom this virtue was any the less important. Of all his legion the finest and the most dear was La Bleue, and from her, then, this loyalty was the more precious.

Still, I knew, as did most others, that it was not he who kept the girl but she who possessed him and could, because of his very obsession with her, lead him and drive him and put him in her pocket when she wanted a recess between the periods of their companionship. She did, in fact, as she had so stoutly insisted, conduct her own life. Of this there was no doubt.

In less than a month after the start of their familiarity she had moved into a new residence and showed herself outfitted with even finer marks of prosperity than she had previously known — in clothing, flashing jewelry and scents of Parisian perfumes. As an enterprise she was beginning to flourish.

For all this she was willing to pay the price of fondness, like so much overhead expenditure; it was the cost of doing business. But she was, nevertheless, in business only for herself; and when Monsieur le colonel presumed to take her over, she set him down at once.

He had objected, it seems, to her almost daily forays into the jungle of masculine desire. If she were his, she must show to him the troop loyalty he expected. Her answer, of course, was a stern refusal to see him further, to admit him through the portal behind which he himself had installed her.

Needless to say, he was stunned by the force of her sudden reply. He begged her to reconsider, to try to understand his position, to remember the fervor with which he loved her. In the end, however, he came round — if not to her way of thinking, at least to her style of living. He wrote to her his deepest apologies and included among them his promise never again to interfere with what he now professed to recognize as her private life. If she would only allow him to come to her, he would be grateful for the opportunity to beg her forgiveness; for he realized how he’d wronged her.

Monsieur le colonel, indeed!

Expressing her inborn sense of boundless generosity, she returned to him the message that she would receive him at her home that very night — at eight o’clock sharp. The audience could not, unfortunately, be a prolonged one; surely he would understand that she had made other arrangements for the remainder of the evening.

He understood. He delighted only in the thought that once again she would be his, and he hers, if not so completely as he might have wished. He poured himself a reassuring cognac and began to practice what he would say to her that night, something properly self-effacing, a statement of deep love which would place her on the pedestal of his imagination. He worked at it all the rest of the afternoon, ignoring even his dinner out of nervous anticipation of the hour of his “confessional.”

At precisely eight o’clock he arrived at her home, his hands moist with anxiousness and his knees quivering just the least bit. When he entered, for the first time in weeks, he saw her sitting on the familiar couch, propped up on her legs with the soles of her feet exposed alongside her. She was dressed in a tight, white sheath of a dress which, because of her casual posture, could not entirely cover her soft, beige thighs.

Around her, much to Marais’s great surprise, was scattered a handful of other men chatting amiably and drinking cheerfully the liquors he himself had stocked for her. She raised her hand as the colonel came through the door and manually ordered him closer to her. Dismissing the formalities of introduction with a few half-spoken words and a short wave of her arm, she turned to the new arrival and bade him fetch her a fresh drink.

He performed the service graciously. Handing her the glass with one of his hands and a present he had brought for her pleasure with the other, he tried to whisper to her quickly an abridged version of the speech he had prepared, but she would have none of it.

“Oh, don’t stand there and mutter,” she admonished him. “These are friends, after all. Anything you feel you must say can surely be said before them.”

Of course, it could not, he thought. All the intimacy he wished to convey in the notes of his rhythmic voice, the emotion of his carefully chosen words, would be made but a mockery aloud before these others. It would be a romantic farce, a cheap barroom melodrama, with himself the leading — the only — player. But, then, was that not exactly what she wanted? In an instant it became painfully clear to him that his audience was to be only a public forum at which he might open himself to the debasement of her whim. Could he allow her to make sport of him so wickedly? He would undoubtedly have considered this question carefully had it not simultaneously occurred to him to ask, “Can I live without this woman?” the latter being more to the point. Clearly, he felt, he could not.

He bent his head and began to address her, raising his eyes to hers only when she insisted she could not hear him. He straightened, cleared his throat and began anew. He could hear the muffled snickers of the men around him as he went along, but he cared little about them once he had got well into his recantation. By the time he had finished, he felt somehow the better for it. He awaited her reply.

“I accept,” she said simply, and it appeared to him that it might be all she intended to say. But there followed her benignant assent a tender promise for the morrow. Eight o’clock again; and she would cancel all her other plans, which meant they would then be alone. Still, for now it was good night. And he left her laughing and drinking and showing various portions of her lovely self to those remaining.

When he had got far enough from the scene of his humiliation to recover a bit of his composure, Marais found that his unsure legs were carrying him directly to La Petite Maison on their own authority. About a dozen paces from the door, where the blistered and peeling paint seemed to pose for him an image of his inner self, he stopped short and refused to be swept further along. He brought his shoulders up high, set his jaw firmly almost to a fault, and turned leftward for his own quarters.

This was the man of whom I now thought, the tortured instrument of a young woman’s successful rise, the latest among a list of successively brighter stars. And now it was my turn, or so I imagined; there had to be a reason. Surely I was not equal to the position of her current suitor. She had passed my level long ago, and there was nothing I could any longer offer her. Or was there?

Here was a girl given to the steady enjoyment of living, seemingly carefree and radiantly alive with beauty and spirit. But if life were for her pleasure, it was also to be made good capital of: the one, in fact, stemmed from the other, and there was no greater joy than the accomplishment of strained endeavor. No, she was not about to fill a void with just any specimen of male matter. Her days were crammed with purpose.

She had worked her way up literally through the ranks, starting at the outset of the war as a sixteen-year-old waitress with the fluid sort of hips that would alternately lull and attract the enlisted men who began to fill this place, Saigon, in rapidly increasing numbers. As her popularity rose, so, too, did her fortune; these French boys — she thought of them always as growing children, whereas she had fully blossomed at an early age — had more money than she had ever imagined. In only a short while she was able to give up her regular — to her, distasteful and even degrading — job in favor of being retained by a constantly shifting group of uniformed patrons. Her own little “Company X,” she called them.

Life was easier then, fun to be with, and she was in complete charge of it. When one of her men got out of hand, he was instantly court-martialed, banished from the field of amorous endeavor. Not many of them, therefore, showed her the least insubordination.

In time, and not too long at that, she had made the necessary acquaintance of ranking soldiers, men instead of mere youths, and she let them ease her into their own circle. She continued to amuse herself with the “little ones,” for they were used to serving, which was as she would have it; but she focused her real attentions on increasingly senior representatives of the military. That, of course, was how she finally got around to Monsieur le colonel.

Now it was my turn, and I could not keep myself from wondering why. Should I accept her gracious nod? I understood full well that I should not, but my curiosity kept nagging from within. At last I reached the reluctant but sensibly firm conclusion that I must not keep the rendezvous, that I must avoid at all costs becoming ensnared like so many others only to end as a possessed and fondness inebriated discard. Whatever her appearance, I knew, her selfish purposes were never far away. I could not allow myself the luxury of deception. I would not go to her.

…

It was already late when I arrived; and I was immediately struck by the exhausting closeness of the room in which she greeted me. Not that there was any measurable lack of space, but something in the atmosphere about me seemed to compress that area into a narrow, almost choking single path leading to the girl in dull white, with the only egress closing in behind me as I moved forward.

“Hello,” she saluted me mildly. “I was wondering whether you would come, but I think I knew you had to.” Something about that vague suggestion of some inner compulsion on my part — perhaps the hint that I could not resist her charm, that I was neither more nor less than any other man — seemed to annoy me more than it should have, and I felt the skin of my cheeks draw tighter.

“You newspapermen are all the same, you know — have to satisfy your little curiosities on every point. Oh, I’ve met a few in my time, and they’re each one the same as the other, just simply must know everything about everybody. I think it’s something of a disease, an obsession, you know, with finding things out.” Her voice was clinically soft as she spoke. But it melted my resentment into plain amusement. “You might,” she went on in that same tone, “at least fix us something to drink — as long as you’re just standing there, I mean.”

“All right,” I agreed, walking across to a small table covered with brandies and whiskey and such. She leaned across the edge of the couch, twisting her body like a lovely serpent, and put a record on the old phonograph beside her; and the scratchy sound of a tired trumpet straining to keep up with the beat of the jazz music it accompanied fast became an integral part of the setting in which it played.

“You don’t like me very much, do you?” she asked, as if it were the next logical matter of business on the evening’s agenda.

“Does it really interest you?” I replied.

“I’m not sure. After I had asked you to come here today, I thought that I cared very much. But now that you ask me so directly, I’m no longer certain that I do.”

There was a moment of silence — not embarrassing, just still. “Oh, well, no matter,” she offered. “Tell me about yourself.”

I began to think of our conversation that afternoon and laughed quietly, thinking that it was she who had just considered me the one filled with inquisitiveness.

“Do you like your work here?” she persisted.

“It’s my job.” I was sipping slowly from my glass of cognac as I watched her variously turn positions in her couch. Her legs were up high now, the snugly fitting dress fallen back to the curves of her middle. “For as long as it lasts.”

“Ah, yes,” she reflected, “for as long as it lasts. And then you will go home, no doubt.”

“Certainly.” And it just did not occur to me that I had answered in the worst possible way.

“What a wonderful thing, to be able to witness the tragedies of life as a spectator and then to leave them and go home when you’ve had enough.”

“That’s not quite the way it is,” I protested mildly. “You see, I — “

“I see only that you come and go.” She was sitting upright now, her legs crossed and her arms partly outstretched, not so much out of anger as from determination. “As you please, come and go.”

“But this is your home, not mine, really.”

“My home? Yes, of course, my home is here. In the midst of all this,” she waved about her lightly, “while men shoot each other like small animals, and no one is sure he will live to see the coming month. The gutter of the world to you, no doubt, but my home still. You will leave, and I will stay; for God knows how many more years of just the same I must stay.”

“But what,” I scratched the back of my head in puzzlement, “has all this to do — “

“I’ll tell you what it means, what it has to do with you.” She raised her voice considerably. “It means that you, while you stand by and look down your polite, well-educated nose at the likes of me, you can take comfort in the fact that for you this place is only a tour of duty which will have a definite ending — soon perhaps. You can afford your disapproval. But me, I must make it here for myself, right here. There will be no one to recall me when I’ve had enough. I must get what I can while I can. That’s what it means.”

I thought I understood her position well enough, but I could not at all imagine her reasons for troubling to explain it to me. Nor could I comprehend the sudden sharpness of her voice. It was an ambush surely, and I wanted to stage my cautious retreat without even bothering to locate the source of this burst of verbal gunfire.

“I’m sorry,” I whispered, which was my mistake. She scooped up the reply as it fell.

“Yes. Yes. You’re terribly sorry. Rome burns to nothing, and you fiddle eagerly on your sorrow.”

“Well,” I suggested in my own defense, “it’s not my fault, you know.” But she didn’t seem to hear me.

“Anyway, now I’ve said it. I suppose you thought I asked you up tonight for other reasons, no? You would, of course. You are that charming, are you? And me, I’m just a little putain? Is that what you were thinking? Is that why you sit so smugly and watch me in Tam’s restaurant for hours? Does it make you feel so good to see the dirty brown prostitute plying her ugly trade — and you, all the time, smacking your sophisticated lips in reproach? Does it make you feel that good?”

It was an unfair attack, I thought, and I was about to counter it boldly when she interrupted once more.

“Go away,” she fairly begged. “I didn’t mean it to be like this, but it is perhaps better that it is so. You did come here tonight to sleep with me, did you not? So, go home now and dream about it. But go home, please.”

I left quietly, without a single word. Outside the door I stopped to light a cigarette and listened for a moment to the muffled sobs from within. I wanted badly to feel sorry for her, but I kept feeling sorry for myself instead. She, after all, had been honest with herself. What was there for me to say?

…

Next morning at nine I was ready to leave for Hanoi. Almost ready, anyway. I was in my room packing a battered piece of light-brown luggage that had never really been unpacked in all the years I’d had it. I was preparing to have a look at the other end of the war.

I knew, of course, in my own mind that this savage war was the same at both its ends, that its only borders were of desperation and hopelessness, that — as before — I would find nothing in the northern sector that I did not already know from elsewhere. Still, there were the small details concerning the administration for mass killing, and these ought responsibly to be covered firsthand; at least, that was the theory behind the move.

I flung a shirt into my bag and mumbled a simple curse. I hadn’t slept particularly well that night, and my head was more than a little groggy, and my eyes burned at the least touch of cigarette smoke. Inside myself I could see a brain that looked strangely like a child’s toy kaleidoscope, except that all its fragments were rendered to the vision through a cast of black and white. At intervals, spaced involuntarily and not at all according to my own moods, this cranial tube was shaken, and a new thought displaced the old one quickly, without even the hint of any resistance. Each new consideration I accepted in its turn, unable to refuse it admission.

Consequently, I did not remember having heard a knock when, after clamping the baggage shut, I turned for my coat and saw her standing there. I do not recall how she looked, except perhaps that her head was slightly lowered, and there was an almost-tear in one eye.

“The door was open,” she excused herself, “so I just came in. I hope it was not very wrong of me.”

“No,” I assured her, managing to maintain the doubtful security of my verbal distance, “not at all. Won’t you sit down?” In my eagerness to keep up propriety for propriety’s and my own sake, I had not noticed as I spoke that the only chair in the room was covered with notebooks, cameras and a large gadget bag filled with various optical complexities and accouterments, some of which I’d yet to use at all. “One moment,” I added hastily, as I scooped the seat clean, and then I waved my arm hospitably from her downward.

“I came to say … that is, well, I did not know you were leaving,” she spoke softly, apparently suspecting that she might otherwise rouse the world.

“Nor did I until yesterday. But, as you said so well, here today and — “

“That’s why I came,” she broke in. “I’m feeling quite a lot better today, and I so wanted to apologize for the way I behaved last night. It was cruel of me, and it was wrong too.”

“Yes, certainly cruel,” I thought aloud.

“And wrong, terribly wrong.”

“No,” I corrected her, “definitely not that. The cruelty lay only in the correctness of your words.” It was true.

“Oh, you mustn’t feel that way. What I said was foolish, like a young girl temperamentally shouting nasty protests at her disapproving father. Anyway, regardless of the reasons why, it was something that need not have been said.”

I smiled lightly. “I’d offer you a drink or something, but I’m afraid it’s rather early. Besides, there’s really nothing to offer.”

“Yes, I see you’re leaving. Probably in a great hurry too, and here I am keeping you — “

“No, please,” I said as she moved to rise; I said it so suddenly as to startle even myself. For some vague reason I was beginning to feel unpardonably close to her, bathing in the radiance of her presence, much as I had wanted it to be quite the other way. It wasn’t anything she had said, I knew, perhaps only that she’d come to me to say it. Sitting quietly in that chair, her knees drawn near to each other and her long, slender hands folded neatly in her lap, she looked the very picture of the mischievous child atoning for her minor wrongs. I felt close to her, indeed — something of a paternal attitude had been sparked inside me.

“No, really, I must,” she answered. “I only came to ask you to forgive me for … oh, I just wasn’t myself. You must understand.” She appeared to be regaining the poise of her former confidence. “You are leaving for the North, no? I shall miss you. Perhaps when you return — you will return? — we can keep that appointment we should have had last night? I was not myself then, you know. I promise you it will not be the same again. Now you must promise me to call when you get back.”

“I promise.” But she was already halfway through the door. She stopped, took a few steps back into the room, and gave me a small kiss on the right side of my freshly shaved face. Then she was gone.

I walked over to a clouded window and looked briefly out at the long miles of Asian misery, wondering what it held for me. In a moment I, too, would be gone.

…

I was away for several weeks, observing in detailed prose the action on another front. And although I had covered it before, I had never before stayed so long. It was the same, the same as previously and the same as elsewhere in the world of abandoned morale. The same people kept dying in the same dirty way.

Skinny little men with boys’ faces clinging to the shrubbery like human stalks, small-scale raids quickly done, ambiguous sympathies strewn along that countryside of peasants whose hopes of peace mingled with an increasing sense of independence, these would beat back the illustrious forces of the French Union; and no one would ever understand why. It had been years now since the bloody contest was begun, and still neither side could claim its certain victory. Soon, I thought. How much longer can it go on?

It did, to be sure, go on just the same for the while I was in Hanoi.

When I returned south, then, I had already sensed within me a bitter, selfish frustration of my own. I was tired. For myself, I wanted a quick ending. Sudden death!

And then there was Dien Bien Phu: Eight weeks of resistance, the long battle approaching the heroic proportions of utter tragedy. The entire war rolled into a month of nights and then some; and when dawn broke, the defenders were badly beaten, ten thousand of their number taken prisoner. The glory of the bewildered French was covered with thick, heavy, plasma-soaked mud.

It was here, too, that my La Bleue lost her general.

Although I never really met him in that while before the holocaust, I did see her a number of times. As she had vowed, that solitary incident that had once come between us was no more. If anything, it was as if that night of stormy bitterness had joined us forever in our loneliness. What confronted me now was only the loveliness I’d remembered, determined never to forget, when we had been apart.

It should have been difficult, indeed, to reconcile the two: the girl whose calculating charms I had known earlier only from my chairborne distance and the pure, unbathed beauty of my presently interminable daydream. That it was not at all so was perhaps a measure of my own life’s unreality, at least for then.

She was truly a friend, an old friend and wonderful. And any desires I may once have held for her in that far-gone world of lifetime moments had melted in their own heat into a perfect love.

We met at Tam’s, appropriately enough, my first afternoon back and spent hours exchanging bits of unrelated narrative to cover over the period of our separation; or, really, I must admit, I listened for hours to her disjointed discourse on the various subjects of her fancy, occasionally offering a line or two of my own. She rambled steadily along, recounting in time every conceivable aspect of her life for my pleasure. Every now and then, apparently becoming aware of the tone of her voice and the turn of her conversation, she would throw back her head of darkened hair in laughter and jokingly address me either as “mon pere” or as “Papa”; and the confessions would resume immediately.

Gradually nearing the present day, she turned suddenly to one side and thrust her arm across the table. Before me flashed a golden bracelet brilliantly highlighting the tender contours of her thin wrist.

“I am doing well for myself, no?” she asked in a voice filled with childish glee, adding with a certain disdain, “Better than before, anyway.”

The “before” referred, of course, to Colonel Marais, whose own well of generosity she had long ago begun to exhaust. The instant of his implied admission that he could no longer afford extravagance naturally dictated his dismissal from among her ranks and with it the erasure from her mind of all but the barest image of the man.

This one was surely better. An untapped reservoir of circumstantial power and wealth, La Farge — Gen. Claude La Farge — had baited his own trap with the unabashed anxiousness of a schoolboy. He held out to her gladly the offer of his position and his fortune, and she was only too respectful of his kindness.

After that first day I saw her on several equally grand occasions, sometimes in my hotel, sometimes at her newly acquired and quite handsome residence. But each time was only as the time before, perhaps even a little more so; and my feeling for her leaped with each encounter. It was as if our life together had been lifted above the locus of objective existence — from the very ashes of destruction our beautifully billowing smoke had risen and reached out now for all the heavens.

Who could account for this change in our relationship, in every sense surely a reformation? Who would even try? For with her there was a liveliness to life, even in that world of death, especially in that world of death.

For we were bound in a universe apart from all others, one remote and distant from the roles we played, each of us in a strictly individual manner. Which is not to deny the essence of those roles and the meaning formerly attached to them, but simply not to take them at all into account, as we performed them but routinely.

Each day was a life in itself, the next entirely uncertain.

She as she was yesterday was too many lifetimes ago to be but dimly perceived in the recesses of a debilitated memory. Myself I had never known well enough to recall.

Even today, as we went about our own pursuits, would be forgotten by the next rising of the sun. And all that would be remembered in tomorrow’s reminiscence would be the unaccountable joys of those precious moments apart, alone, forever alone. The rest, it did not matter.

A child, a dear and dependent child, I took her by the hand and led her along what ways I know not — and knew not then. The going was itself the destination. The long walks, the repose between, so long as they were joined with the other’s, were happy. Only to have her in my care, to have her at my side as a shadow follows its guardian to the setting of a gold and crimson sky, this was my simple delight.

I did not realize the extent of my own reliance on the protection of her love, that which had so readily transported me from within the confines of the absolute and beyond the reach of the actual.

Then, in the summer, I got my notice to return home as soon as the already accepted cease-fire program had gone into effect. But I was not fully anxious for that moment of departure. Somehow the misery and love I had known there in Indochina had been grafted onto my life in the real world, and they suddenly seemed as much a part of me as any other.

I saw her at Tam’s on the tenth of August. She was sitting alone; the first time I could remember ever having seen her wanting for the company of her male admirers. Her back was to the door, and she did not hear my approach.

“Hello.” I spoke low and watched her swing around in her chair, dropping her feet loudly from the table to the floor in turning.

“Oh, hello,” she returned with a vague smile and the swallow of her remaining drink. There was a moment’s pause, then, “I hear you are leaving us, no?”

“Yes,” I answered.

“You don’t sound very pleased.”

“I’m not really sure I am.”

“Oh, but you must be,” she urged, apparently noting the dejection of my quiet reply. “You were not meant for a place like this. You must go back to your own life. You will see, it will be better.”

“Yes, I know,” I said. “It’s just that I can’t help …” She didn’t seem to have heard me at all.

“Do you still perhaps remember that night I was so cruel to you?” As if either of us was ever likely to forget it entirely. “I condemned you for being only a visitor to our … well, anyway, I was wrong, you know. I told you so next day. I was wrong, you see, because I did not stop to realize that it was as it should be. Everyone, I think, is made for his own time and place — even if he does not seem to fit into it very well.” She laughed a thin laugh at this last, and I knew I had to leave. Most likely I should never have come.

“You must not feel you are wrong to go,” she concluded, sensing within me the problem I had not myself yet understood. “You have done your job here, and it is time to leave. That is the way of the world, my dear, and for that the world is filled with memories. Only be sure, if you will, to include me among your own.” A hundred thousand words filled my head at once, but none of them was to be spoken. There was, after all, nothing more to say.

I leaned over and kissed her lightly on her cheek. There was a small, pearl-like tear refracting the colors of the stark light beneath her eye, I saw, but the rest of her face maintained the structure of stubborn serenity.

“Au revoir,” she called to me as I was leaving. “Until we meet …” Outside there was only scattered noise, and I walked slowly back to my room.

Every now and then I received an affectionate letter from her, reminding me of our friendship and recounting for my delight one or another of her further exploits; her words were chosen, it seemed, for their pleasantness and their joy, and her verbal manner held secure the increasingly tenuous bonds between us.

But eight years is still a long time, and after a while even her mail stopped coming. I hadn’t heard from her in more than a year, our lives seeming to have grown farther apart, when there arrived at my office one morning a thin, gray envelope addressed in her own graceful hand. Hurriedly, almost impatiently, I tore it open …

October 11, 1962

My Dear,

Well, my time is finally running out, and I must write this last letter with great haste. Please bear with any faults of penmanship which illustrate my hurriedness. Please forgive also my inexcusable lapse in writing to you these past several months — my God, it must be even longer than that by now. Never feel, please, if only for the sake of my eternal peace, never feel that even for an instant could I bring myself to forget you. Surely you must know that, as my few treasures are counted up, you are by far the most precious. The short while that I knew you here was, for me, a lifetime of happiness. I have no right to ask for more.

And, before I forget, I must offer you my congratulations on your new position. You see, I keep in touch with you without your even knowing it. (Really, I learned the good news from Charles Vosse, the one you always said looked like a kangaroo, when he was back briefly in Saigon right after that horrid palace bombing.) It must be an awful responsibility being the foreign news editor of a big newspaper, but I haven’t the least doubt that you are performing admirably in the job.

You see, I once told you that each of us has his own place. At last, you have found yours, and for that I am so glad. Now I will go to find mine — although a little reluctantly, of course.

It’s funny when you stop to think about it, I who was forever uncommitted now having my commitments made for me. I should have been more careful, I suppose, of my associations, but who expected so high-ranking a man to be “involved”? Alas, my greatest conquest and my surest defeat! And to be made the loser when you have not even played the silly game, what a true pity!

There is so very much that I want to tell you but cannot. This short note, this last, must be sent on its devious way while there is still the time, and I must close it here (oh, how I hate the very thought). Soon, they will be coming for me.

Do not feel sorry, please, for we have shared too much happiness to have it spoiled by this. You must go on with your own life and your work. That is the important thing. Please, please, no regrets. Only memories. Think of me as you will, but think of me forever — as I will dream of you in my eternal reverie.

A demain,

Charlie

Suddenly I had a queer, nagging need for the taste of a cigarette. I wanted, too, to uncross my legs, now tingling with the brisk sensations of muscular drowsiness. I wanted to stand and stretch my back and wave my arms and shake my head and shout that it could not be so.

Instead, I simply sat. Gazing out the window that clear autumn day, I let my mind drift freely with the flow of time. It was a long moment of divorce from the awareness of present time, of swimming through a sea of sentimental bliss and bathing in the delights of another unappreciated day; but it could be no more than a mere pause in the march away from yesterday.

I looked again at the date of the letter. It was five days old. Obstinately refusing to believe what it implied, I immediately contacted our correspondent in Saigon, one Louis Graff, inquiring as to recent arrests and possible executions by the government. I specifically mentioned a lead we had supposedly received on a young woman known to us only as La Bleue.

My cable was answered that same evening:

ONLY FEW ARRESTS RECENTLY INCLUDING WOMAN CALLED LA BLEUE LATE LAST WEEK STOP UNKNOW OFFICIALLY HER FATE BUT GOVERNMENT SOURCES INDICATE EXECUTION OVER WEEKEND ON CONSPIRACY CHARGES STOP NO RPT NO MAJOR FIGURES AMONG RECENT ARRESTS FINIS GRAFF

When I reached the street that night, it was raining — not a heavy rain but a sort of steady, misty spray that covered my head as I walked idly along. A few small droplets began independently to roll down the sides of my face; and strangely, I felt all the better for them. Each of us has his time and place, I unconvincingly and almost mournfully repeated over and over to myself. Every sight, every sound, every bare sensation, all seemed to remind me of that girl I’d once been able to know. Or perhaps, I thought, I had never really known her at all. Perhaps she had been only the beautiful fantasy of my own spiritual lust.

No matter. It was over now, swept away as the incoming tide tears down the sand castles of a child’s dreams. And I was very tired.

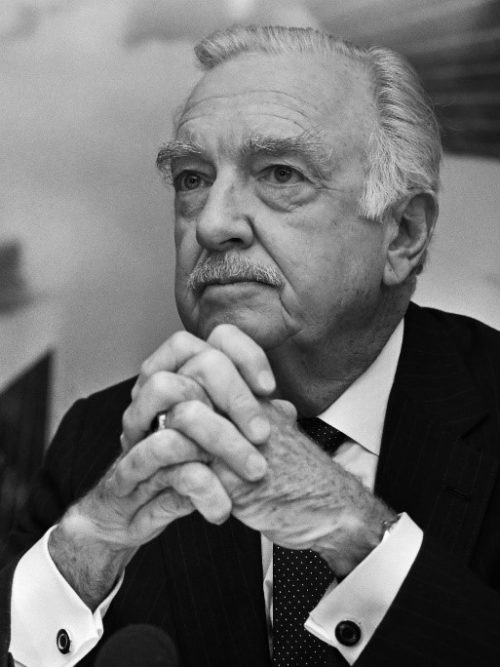

Considering History: Walter Cronkite, David Halberstam, and Two Legacies of Adversarial Journalism

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Fifty years ago this evening, on February 27, 1968, legendary CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite concluded a special report on the ongoing conflict in Vietnam with a striking three-minute commentary. The special report had cast a long and searching look at the haphazard progress and challenges of the “police action” in Southeast Asia, but Cronkite’s closing commentary went much further still.

Acknowledging that his “analysis must be speculative, personal, subjective,” he nonetheless laid bare the stark realities of the situation in Vietnam: “For it seems now more certain than ever, that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate. To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past.”

Cronkite’s sober realism wasn’t just an overarching attempt to counter such optimistic narratives of the war—it was also quite specifically adversarial to the perspectives coming out of the American military and political leadership. “With as much restraint as I could,” Cronkite narrated, “I turned to our own leaders whose idea of negotiation seemed frozen in memories of General McArthur’s encounter with the Japanese aboard the Battleship Missouri. … We’ve been too often disappointed by the optimism of the American leaders.” As he so often did, Cronkite presented this adversarial stance in a restrained and civil way, a tone befitting his role as an elder statesman of American journalism. But his opposition to the narratives coming out of Washington was clear and crucial nonetheless.

That restrained, civil, and statesmanlike form of rebuke could be called public adversarial journalism, and was a key facet of Cronkite’s voice and role throughout his decades on the air. It had the ability to shift national conversations in a gentle but very real way, framing a new way of understanding unfolding histories and issues for both Cronkite’s listeners and the powerful figures to whom he was speaking his truths. Building on the legacy of influential predecessors like Edward R. Murrow, and making this critical tone a more consistent part of his efforts as anchor than any of his contemporaries, Cronkite’s public adversarial journalism became a vital component of the television news landscape throughout the 1960s and 70s.

Yet while such public adversarial journalism has vital roles to play in changing national conversations by speaking uncomfortable truths, it is not necessarily as well-equipped for investigating and uncovering such truths. For that, a more private adversarial journalism is needed, one that confronts leaders and spin artists directly, calls them out on their partial or false representations, and works to find the truth that lies behind them. In the same period as Cronkite’s public stance on the Vietnam War, a young investigative journalist named David Halberstam modeled this form of private adversarial journalism, helping shift the relationship of war journalists to the military effort in the process.

Halberstam told the story of his most striking and inspiring moment of private adversarial journalism in a 2005 speech to the Columbia School of Journalism:

Probably the moment I am proudest of in my career is this: By the fall of 1963, I was one of a small group of reporters in Saigon— we had enraged Washington and Saigon by filing pessimistic dispatches on the war. In particular, my young colleague, Neil Sheehan, and I were considered the enemy. The president of the United States, JFK, had already asked the publisher to pull me.

One day that fall, there was a major battle in the Delta (the Americans were not yet in a full combat role; they were in an advising and support role). MACV—the American military command— tried to keep out all reporters so they could control the information. Neil and I spent the day pushing hard to get there—calling everyone, including Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge and General Paul Harkins. With no luck, of course.

In those days, the military had a daily late afternoon briefing given by a major or a captain, called the Five O’clock Follies, because of the generally low value of the information.

On this particular day, the briefing was different, given not by a ajor but by a major general, Dick Stilwell, the smoothest young general in Saigon. It was in a different room and every general and every bird colonel in the country was there. Picture if you will rather small room, about the size of a classroom, with about 10 or 12 reporters there in the center of the room. And in the back, and outside, some 40 military officers, all of them big time brass. It was clearly an attempt to intimidate us.

General Stilwell tried to take the intimidation a step further. He began by saying that Neil and I had bothered General Harkins and Ambassador Lodge and other VIPs, and we were not to do it again. Period.

And I stood up, my heart beating wildly—and told him that we were not his corporals or privates, that we worked for The New York Times and UP and AP and Newsweek, not for the Department of Defense.

I said that we knew that 30 American helicopters and perhaps 150 American soldiers had gone into battle, and the American people had a right to know what happened.

Through this and many other moments of private adversarial journalism, Halberstam and colleagues like Sheehan were able to uncover the truth of what was happening with US forces and efforts in Vietnam—a truth that became a crucial influence on shifting the perspectives on the war of public journalists and figures like Cronkite.

While they differ in tone, role, and other specifics, Cronkite’s and Halberstam’s public and private adversarial journalism are ultimately complementary, each a necessary part of a journalistic enterprise that pursues truth and presents it to its audiences and society. The legacies of both these men and moments remain vital models for American journalism.

Your Weekly Checkup: Don’t Sabotage Your Health with Ultra-processed Foods

“Your Weekly Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

As I ate my cereal for breakfast this morning, I read the ingredients listed on the box. In addition to the usual alphabet of vitamins, the cereal contained phosphorus, zinc, iron, magnesium, syrup, sugar, fats, and a variety of oils, salt, glycerin, molasses, soy, lecithin, corn starch…and the list went on. Can all these be good for me, I wondered?

According to a recent article in the British Medical Journal, ultra-processed foods packed with artificial flavors, additives, or emulsifiers typically contain more calories, sugar, fats, and salt than non-processed foods. People relying on such a diet tend to be more overweight and more likely to have cardiovascular problems or diabetes. A study in 2016 found that 50-60% of the calories in the average American, Canadian, and United Kingdom diets come from this kind of food, and more of the developing world is beginning to eat this way.

Several studies have also found a link between processed foods and cancer. Eating lots of processed meat like hot dogs is associated with an increased risk of bowel cancer. French researchers, analyzing 24-hour dietary records of nearly 105,000 adults in the NutriNet-Santé study, an ongoing web-based cohort launched in 2009, found that a 10% increase in the proportion of ultra-processed fats and sauces, sugary products, and drinks was associated with an increased risk for overall cancer, and ultra-processed sugary products were associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.

What might be the cause of a cancer relationship? Ultra-processed foods can contain contaminants with cancer-causing properties such as those found in heat treated processed foods. In addition, food packaging may contain carcinogenic materials that come in contact with the foods. Some food additives such as sodium nitrite in processed meat may be carcinogenic.

Importantly, food experts caution against strict interpretation of these results because of many confounding factors such as the lifestyle of those who eat these products: they may be more likely to smoke, not get enough exercise, and not eat healthy foods that might reduce risks of cancer.

What is the best advice? Eat a balanced and diversified diet containing real foods such as fresh, dried, ground, chilled, frozen, pasteurized, or fermented foods like fruits, vegetables, rice, pasta, eggs, meat, fish, or milk. Resist—as much as possible—mass produced packaged breads and buns; sweet packaged snacks, confectionery and desserts; and sodas and sweetened drinks. Avoid reconstituted meat products with added preservatives found in some meats, poultry, and fish nuggets. Instant noodles and soups, frozen or shelf stable ready meals, and other food products made mostly or entirely from sugar, oils and fats, modified starches, and protein isolates are probably not good, either. They often contain flavoring agents, colors, emulsifiers, humectants, non-sugar sweeteners, and other additives to disguise undesirable qualities of the final product.

If your conscience tweaks you after sneaking that jelly donut or a side of bacon with those eggs, remember what I’ve said before: moderation in all things, including moderation.

Why Tattoos Are So Popular

If it seems to you that you’ve lately been seeing tattoos everywhere and on nearly everyone, you’re not hallucinating. One of the best experts to ask about the flourishing trend may be Friday Jones, a prominent American tattoo artist with an elite worldwide clientele (“I love my oligarchs, here and in Europe — but we don’t talk politics.”) and a visceral passion for her art.

“Oh, the money is so easy these days. I feel guilty,” Jones gushed by phone when I found her in New Orleans, which is currently her American base. “I’ve been doing tattoos for 26 years. It’s amazing, watching the whole arc of the business.”

Me, I’m confused and conflicted, the blazing arc notwithstanding. Our as-they-come-into-this-world bodies are not beautiful enough? They need embellishment? Colorful drawings of capuchin monkeys, F-15 fighter jets, stern-faced moms?