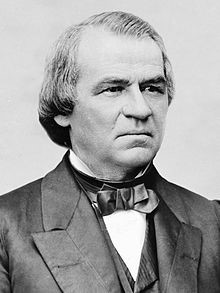

Considering how often it is demanded by political opponents in recent years, impeachment of the president has rarely been used, and it’s never resulted in a president’s removal from office. Only two presidents have been impeached: Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton. Many are familiar with the events surrounding the Clinton spectacle, but fewer know what led to President Johnson’s impeachment in the tumultuous months after Lincoln’s assassination and the end of the Civil War.

Andrew Johnson’s impeachment and trial shows how difficult indicting a president can be — even when it has the support of the Senate’s majority. This timeline walks you through the contentious details from 150 years ago. (For more on how impeachment works, read our “Quick Guide to Impeachment.”)

April 15, 1865

In the hours following the death of President Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, is sworn into office. When the Civil War had started, he’d been the governor of Tennessee and a valuable union supporter in a border state. In 1864, after he was elected vice president, he repeatedly promised to hang all the leaders of the Confederacy when the war was over. Now, as president, and with the southern leaders powerless, he would have that chance.

But Lincoln died before detailing how he planned to reunify the country. Johnson only knows Lincoln wanted to extend clemency and bring the seceded states back into the union as quickly as possible.

May 29, 1865

Johnson offers amnesty to all ex-rebels who hold property valued at less than $20,000, which excludes propertied men of the South who had been leaders of the secession. However, many of these leaders come to Washington to ask for clemency, which Johnson usually gives.

1865-1866

Johnson faces a growing opposition in Congress from legislators who are concerned that the former Confederate states are rebuilding their old status quo, electing their old leaders, and denying civil rights to emancipated slaves. They learn that Southern states are passing laws against vagrancy. These “Black Codes” require many African-Americans to sign year-long work contracts or face the risk of fine or imprisonment, in effect forcing them back onto plantations.

Not wanting to lose what the North had fought for, these legislators, who are now termed Republican Radicals, mount increasing opposition to Johnson.

1866

Bypassing Congress, Johnson tours northern states to build public support for his lenient plans for reconstruction, but fails to win followers in any appreciable numbers.

During his tour, President Johnson promises to eject members of the Cabinet he has inherited from Lincoln who are now opposing his policies toward the South. He says Edwin Stanton, secretary of war and one of the leading radicals, is one of the first he will dismiss.

January 1867

Congressman Thaddeus Stevens is strongly opposed to Johnson’s conciliatory approach to the South. To prevent the Old South from returning to power, Stevens introduces a new Reconstruction Act. It would dismantle the Southern state governments and establish five military districts with military governors. They would govern the states until new constitutions that ensure suffrage for all voters are written.

March 2, 1867

Congress, led by Stevens, responds to Johnson’s threat to dismiss Stanton by passing the Tenure of Office Act. It would prohibit the president from removing any government official who’d been approved by the Senate without first obtaining the Senate’s permission.

Johnson vetoes the act. The following day, Congress overrides a presidential veto for the first time to make the Tenure of Office Act law.

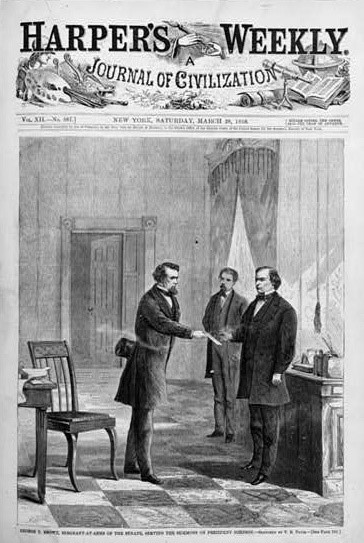

February 21, 1868

Believing the Tenure of Office Act to be unconstitutional, Johnson tells Congress he is unilaterally ordering Stanton to leave the office of secretary of war.

February 24, 1868

Stevens demands that Johnson be impeached. The House of Representatives votes to impeach Johnson, with 128 Republicans voting for the measure and 47 Democrats opposing it.

February 29, 1868

Eleven articles of impeachment are agreed upon. Most are based on Johnson’s action of dismissing Stanton.

March 30, 1868

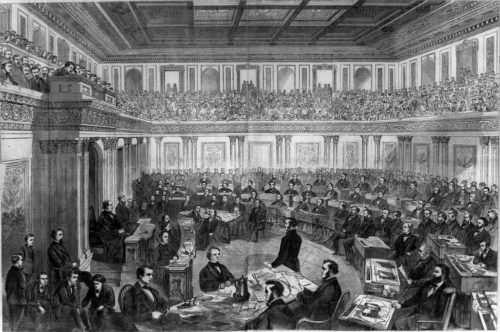

The trial in the Senate begins.

May 16, 1868

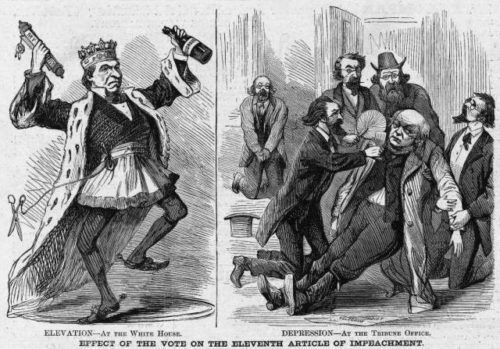

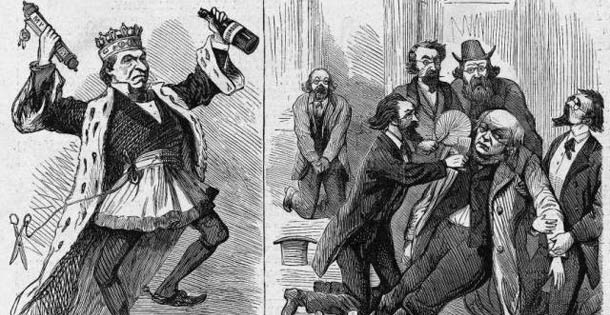

The Senate votes on one of the 11 articles of impeachment. It has been chosen for the first vote because it has the greatest support in the Senate. The vote, 35 to 19, falls one vote short of the two-thirds majority needed for conviction.

May 26, 1868

The Republicans aren’t prepared for defeat. They come back on this day to vote on other articles of impeachment, but again fail to gain a two-thirds majority. Johnson remains president.

Aftermath

Stanton leaves his position as secretary of war. Johnson finishes his term the following year and returns to Tennessee. In 1875, he becomes the only former president to be elected to the senate, but dies a few months later.

The vote that prevented conviction of Johnson, a Democrat, was cast by a Republican who voted against his party’s leaders. He was Kansas senator Edmund Ross. He said he changed his mind at the last minute and voted “not guilty” because, upon reflection, he voted from his conscience. He believed the charges didn’t warrant conviction. Yet his motives might not have been entirely driven by his principles. The next month, he asked President Johnson for, and received, six political appointments for his friends, reminding Johnson of the supporting vote he cast in the impeachment trial.

Featured image: Harper’s Weekly, May 30, 1868

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Wow! I love this article! Thank you for writing this.

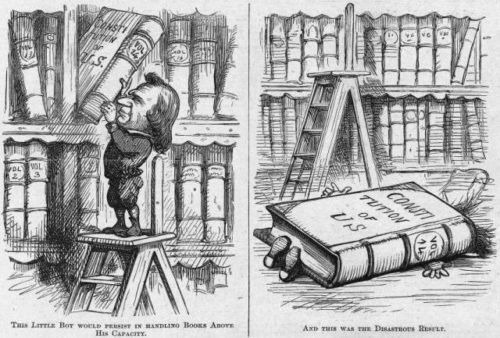

Interesting details noticed in this timeline, gives me the assertion that the president was indeed NOT guilty. To put it within the context of a simple example; this is like giving a child a responsibility and freedom to perform a task, and not allowing him or her the right to make mistakes. It would go against basic human principles.- “We are all humans, we not all always agree, and we all make mistakes” -It was, from this logic perspective, an childish opposition.

I understand the times and the importance of that event. Like the congress I would have been very worried for many VALID and IMPORTANT reasons. But o be fair to our great constitution and to the truth, the congress seemed to be the one engaging into two different impeachable offences, NOT the president.

Coincidentally, I would definitely ask back for some favors if I had to; it is another human trait.

Thank you Jeff, for writing this great timeline!

This is so fantastic. History always amazes me! How close we came to injustice. One vote made the difference!