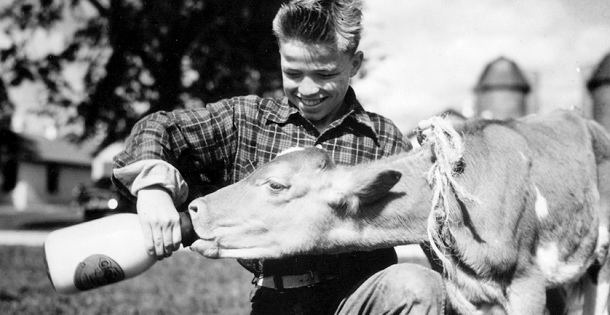

Sixty-six years ago, James Tate rose at 4:30 a.m. sharp each morning to milk a handful of cows in time for his 6:30 a.m. breakfast. This strict routine taught him responsibility and work ethic as a teen. Through pouring rain, headaches, and unruly sows, Tate learned “the cows always have to be milked.”

Tate didn’t grow up in the Midwest or even in a rural area; he attended the Church Farm School just 20 miles outside of Philadelphia.

The Episcopal boarding school for boys is celebrating its centennial in April. Although dairy farming is no longer a part of the curriculum, CFS continues its focus on disadvantaged boys that was the subject of a 1954 article in this magazine titled “The School that Came from Nothing.” Ashley Halsey, Jr. reported for the Post on the humble origins of CFS and its eccentric brand of education. More than 60 years later, the ambitious “school that came from nothing” remains the legacy of one man’s wishful thinking that worked.

The school was founded by Charles Shreiner, a stern Episcopal priest dubbed “the Colonel” by his earlier role in a Pennsylvania Boys’ Brigade. To realize his dream of opening a school for fatherless boys — as he had been himself — the Colonel cozied up to Philadelphian philanthropists and set out to work on his 125-acre plot in Glenloch, Pennsylvania. Over the years, the farm grew in serendipitous strokes: oil and electric companies paid to cross the land with their pipelines and power lines, and confident donors filled out the operation with tools — both educational and agricultural.

At its largest, the Church Farm School spanned 1,600 acres and raised cows, chickens, and hogs along with a host of crops. The bulk of the farm’s products were sold to sustain the school, and some of the bounty was packaged as gifts for its faithful benefactors. Tate recalls the peony bouquets and sausages the boys prepared to send off as tokens of thanks. If a donor was lucky, they might receive a parcel of scrapple in the mail. The pork by-product has fallen out of fashion, but in the ’50s Tate and his fellow farmers skimmed the fat from the mush and wrapped it up as “Church Farm School Scrapple.”

The school’s scrapple days are over. In the 21st century, CFS engages its students in STEAM (Science Technology Engineering Arts and Mathematics) learning. Reverend Edmund Sherrill took the helm of CFS 9 years ago following three generations of Shreiner leadership.

Since the last write-up of CFS in this magazine in 1954, the school has transformed into a diverse community of hands-on college preparation. In the student body of around 200 boys, Sherrill says 80 percent are students of color, and the school has boasted a 100 percent college admission rate for seven years. “I have to believe that the founder would be pleased that the school’s mission is intact,” Sherrill says, “to bring opportunity to kids who wouldn’t otherwise be able to access it.” Eighty-eight percent of the school’s students receive financial aid.

Mohammed Emun graduated from CFS in 2017. He refers to the school as “the farm” even though the four silos that watch over its campus no longer hold grain. Emun attends Tufts University in Massachusetts, and he is planning to combine his interests in computer science and psychology to study cognitive brain science. Emun says his days at the farm were filled with challenging coursework, multidisciplinary extracurriculars, and community service. “I see some other students having a hard time adjusting to college, but I think it’s easier for me since I learned independence at a boarding school,” he says. Emun left his home in Lansdowne, Pennsylvania to attend boarding school at age 11. While at CFS, he edited the school’s yearbook, took part in student council and multicultural club, and even volunteered with Habitats for Humanity.

In its century of growth and transformation, CFS has come to focus on maintaining a small student body — around 200 boys — and developing an arts-integrated education in an effort to create global citizens. “Curriculum has changed from the delivery of information to the utilization of information,” Rev. Sherrill says. By blending arts and design into a STEM education, Sherrill believes the school’s curriculum is addressing the larger questions behind utility and function, like, “What kind of world are we designing to live in?”

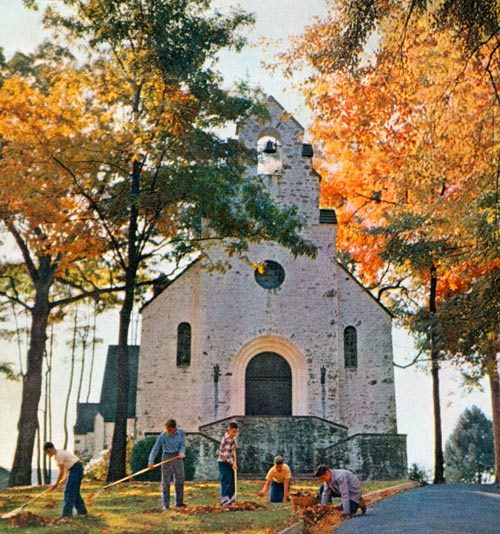

Creative problem-solving has a long history at CFS, starting with the Colonel’s bureaucratic backflips that kept the school running through world wars and the Great Depression. The still-standing 1928 gothic-style chapel was erected with the help of some of its pioneering students, who carved the lumber and laid the stone for the structure. While agriculture was a focal point in the earlier days of the school, for some it served only as a larger lesson in accountability.

James Tate spent years milking cows and cutting corn when it was “high as an elephant’s eye,” but he didn’t go on to a career in animal husbandry. Tate graduated from Penn State with a degree in liberal arts, and found himself in an advertising career in New York City by the late ’60s. Even after running his own advertising firm, he never forgot his time at CFS. Tate served as the president of the school’s alumni association for 20 years, and he now resides about 10 miles from campus.

Tate is pleased with the direction of the school as it enters its second hundred years. He believes the changing curriculum is necessary in a 21st-century world. When he steps onto campus, the changes are obvious: baseball fields and tennis courts have replaced pastures, and farmland has given way to a solar panel farm. What endures, however, at CFS is the attitude of the boys toward their school: “I am amazed at how strongly they feel about the school when I see them on campus,” Tate says, “They talk about it in glowing terms.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now