How does it feel to surpass everything you’ve ever done? What goes through your mind while you’re succeeding beyond your wildest expectations?

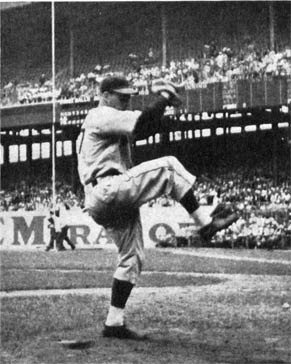

For Cincinnati pitcher Johnny Vander Meer, the realization that he was close to setting a major league record didn’t occur to him until someone else told him. As he was walking to the pitcher’s mound just before the sixth inning in a 1938 game against the Boston Bees, the opposing team’s manager called out to him, “We’ll get a hit this inning for sure.” Only then did Vander Meer realize that, so far, he had pitched a no-hit game.

In an article he later wrote for the Post (“Two Games Don’t Make a Pitcher,” August 27, 1938), Vander Meer recalled that the news didn’t bother him. He wasn’t trying for a no-hitter, after all. But as the innings passed and he continued to frustrate the Boston batters, Vander Meer began to realize he might soon join the small group of athletes who have pitched no-hitters.

In the ninth inning, the game seemed to be slipping from his grasp. The final batter almost ruined things when he hit a pitch toward third base. But Vander Meer had so much confidence in his team’s third baseman, “I started walking to the bench even before the play was completed.”

Vander Meer had pitched a no-hit game—his first and, given their rarity, likely to be his only.

Yet, four days later, in a game against the Brooklyn Dodgers, he did it again. It was the first time a pitcher had thrown two no-hit games in a row. It hasn’t been done since.

We ask a moment’s indulgence from baseball fans to explain to unschooled readers what makes a no-hitter so remarkable. In a no-hit game, a pitcher throws so well that the opposing team never productively puts bat to ball. They may hit a foul or put a ball “in play” that is caught for an out, but there are no base hits. It’s hard enough to do against a single batter; against 27 batters, it’s a rare achievement. More than 380,000 major league games have been played since 1876. Only 277 were no-hitters, which averages to about two per year.

Remarkably, few pitchers have thrown more than one no-hitter in their career. Vander Meer threw two, both within a week of each other.

What makes the achievement more remarkable is the fact that Vander Meer was still a young, unseasoned player. He hadn’t shown a lot of talent in his brief time in the major leagues. He had only been brought up from the farm team the year before. After winning three games and losing four, he was sent back to the minors. Late in ’37, Cincinnati brought him back and signed him for the next season.

Vander Meer didn’t feel confident about his pitching that spring. Then, in a May game, it all came together. On May 20, he shut out the New York Giants. Soon after, on June 11, came his first no-hitter.

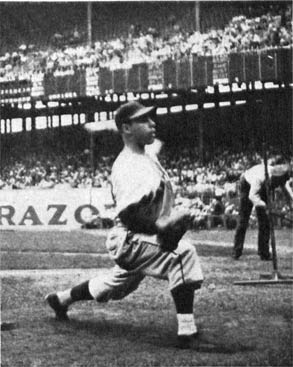

Few expected him to achieve another when he started his next game on June 15. But when he quickly struck out the first Brooklyn Dodger, a gust of hope fanned through the Cincinnati fans in Ebbets Field. He wrote that after retiring two more batters, he felt everyone on the Cincinnati bench and in the crowd of 38,000 thinking about his chances of pitching another no-hitter.

Vander Meer firmly pushed this idea from his mind, as well as the fact that this was the first game his father and mother saw him pitch. Instead, he focused on pitching as evenly and as capably as he could.

Twice, he got into trouble. In the seventh inning, he walked two players. But he struck out the next man, and the last batter was forced out by Cincinnati’s second baseman.

By the ninth inning, the crowd was on its feet. Both Brooklyn and Cincinnati fans were cheering lustily for another no-hitter. Vander Meer barely heard them; the sound of their roaring came to him “like the faraway buzzing of bees.”

He had to work on distancing himself from the crowd’s expectations, but he could feel himself responding to their pressure. “I started hurrying my delivery. I wanted to get the game over fast,” Vander Meet wrote. He struck out the first Brooklyn batter. Now only two remained before he could set a major-league record.

“Then,” he wrote, “I lost control.” He walked the next batter. And the next one. And the next one. The bases were now loaded.

The Cincinnati manager came out to the mound. He quietly told Vander Meer, “You are trying to put too much on the ball, John. Just get it over there.” As he turned back to the dugout, he added, “Those hitters up there are scared to death.”

It wasn’t the words that restored Vander Meer’s confidence, but the way they were spoken. He felt his confidence and control return. He relaxed as he pitched to the next Dodger, who hit a groundball that was fielded by the third baseman, and a runner was forced out at the plate. The last Dodger came to bat, and hit a shallow fly ball, which the Cincinnati center fielder caught for the third out. And the crowd, we can safely assume, exploded into pandemonium.

Except for that last inning, which remained vivid in his memory, Vander Meer could recall very little of those two record-setting games “except a few little odds and ends. I remember Babe Ruth coming on the field to shake hands with me before the Brooklyn game. Otherwise, the evening passed in a haze.”

Obviously, Cincinnati fans were hoping for a third, sequential no-hitter in the next game. Again Vander Meer faced the Boston Bees. But in the third inning, Debs Garms, a Boston outfielder, hit a single. Vander Meer felt immediate relief. “I think if I’d have had a 10-dollar bill in my baseball pants, I’d have gone over to first base and handed it to Garms. By that time the tension on me was getting pretty severe and I was happy when the hitless spell, which had lasted through 22 and 2/3 innings, finally was broken.”

Unfortunately, his double victory was the high point of Vander Meer’s career. He quickly settled down to become a competent pitcher who continued to have problems with ball control. He lasted only a few seasons in the major league before returning to the minors.

How does it feel to know you once had the skill to pitch back-to-back no-hitters, and maybe still had it, but could no longer find it inside yourself?

Vander Meer hung on with baseball, moving between minor league teams until, in 1952, he wound up in the Texas league with the Tulsa Oilers. Then, one night while playing the Beaumont Roughnecks, the old magic returned. On that night, Johnny Vander Meer, after a 14-year drought, pitched a third no-hit game.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now