If you’re reading this, you’ve probably forgotten how difficult it was to learn English. Our language is peculiarly complicated because it’s a mashup of Romance and Germanic tongues that is governed by a set of inconsistent rules. But a big obstacle to mastering English is not our grammar, but our spelling. There is little consistency between the way we spell English words and the way we pronounce them.

Consider the student of English trying to learn that the sound of a long e is spelled seven different ways (he, thee, heat, seize, key, grief, and ski.) Or that the k sound can be represented by a c, ck, lk, ch, or que.

Furthermore, our spelling rules are riddled with exceptions. (For example, most of us are familiar with the rule that requires us to place i before e, except after the letter c. It’s a good rule so long as you don’t apply it to neighbor, weigh, eight, their, leisure, seize, vein, species, science, efficient, etc.)

Today, one reformer, London investment banker Jaber George Jabbour, is trying to straighten out the chaos of our spelling. He developed SaypYu (Spell As You Pronounce Universal), a simplified, phonetic alphabet that works with English and other languages.

This alphabet connects every spoken sound in English to a single character, or group of characters. Consequently, there is only one spelling for every word, and a reliable pronunciation guide for the English vocabulary. (Yu kan tray dhis nyu alfɘbet at his websayt: saypyu.com).

According to Jabbour, “If all words in all languages were spelled phonetically, using a simplified phonetic alphabet such as SaypYu, we would be able to learn foreign languages much more easily. We could become more open to other cultures, which might make our cosmopolitan world a more peaceful and harmonious place.

“Schoolchildren who spend less time memorizing the spelling of words and more time mastering other subject’s such as math, programming, and foreign languages, will be better equipped to compete in a global marketplace.”

Jabbour is very clear on the fact that he is not trying to change spelling. At this point, SaypYu is only intended as an online guide to international communication.

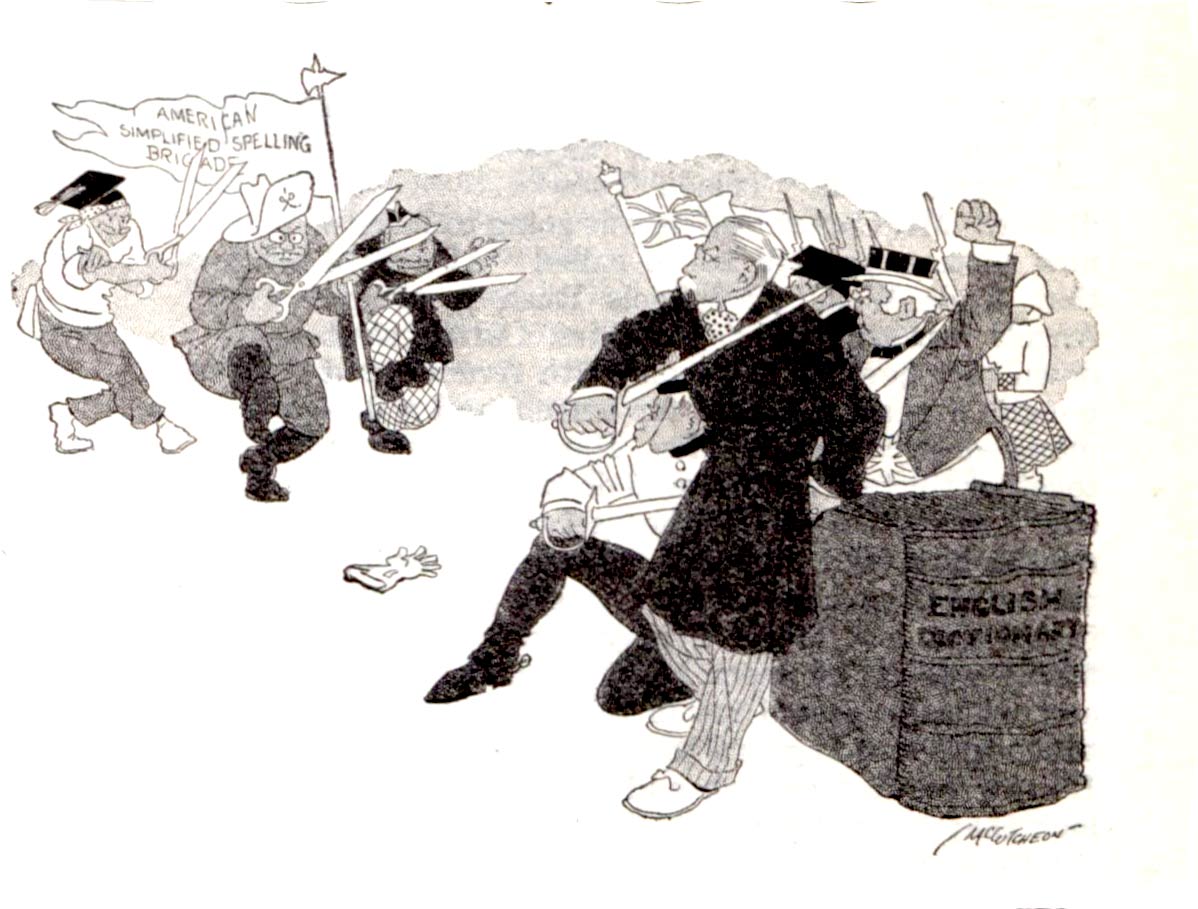

But Jabbour isn’t the first reformer. Several times in our history, language advocates have tried to modify our spelling. One of the greatest efforts began in the 1900s, when Andrew Carnegie funded the Simplified Spelling Board. Within months, this collection of professors and editors created new spellings for a list of 300 commonly used words. Most of the changes simply removed unnecessary letters: Debt became det, money became mony, are became ar, and walked became walkd.

Such a scheme may seem fanciful to us today, but Americans at the turn of the century were in the mood for modernization and reforms. The Post editors were particularly enthused about simplified spelling. In a January 28, 1905, editorial, they claimed that 10 percent of the letters in any document were unnecessary. If these letters could be eliminated, Americans could save 10 percent of their time in writing, composing, printing, and binding the document: “in short, ten per cent of all the labor and cost of writing and publication, a matter of untold millions.”

By setting standards for phonetics, the Post believed, the country would encourage national literacy. Moreover, it might bring global harmony. The editorial states that, “the first step toward a world-wide era of peace and good will is mutual understanding among the nations; and if any language is fitted to become universal by its innate superiority and the might of those who speak it, it is English.” That is, English with an understandable method of spelling.

The spelling reformers soon found they had a powerful ally in Theodore Roosevelt. In 1906, the president ordered the Government Printing Office to use the reformed spelling in government documents. However, Congress refused to go along with Roosevelt’s call to use simplified spelling in the Congressional Record. In the end, according to a senator’s aide who was writing for the Post (“The Senator’s Secretary,” January 12, 1907), “the President, personally, reserved the right to shoot tho and thru and prest and thoroly at the Congress in his messages.” Congress simply changed the spelling in Roosevelt’s speeches back to the traditional style before they were printed. Sensing that the public opinion was shifting away from his crusade, Roosevelt didn’t push the point. He let his remarks appear in the Record with the traditional spelling.

As the simplified spelling movement faded away, spelling reformers were starting to look at the alphabet of Esperanto. This newly created language had been developed as a globally common, easy-to-learn alternative to the world’s dominant languages. Being wholly new, it avoided all the curious spellings and pronunciations that came with legacy languages. But Esperanto caught on no better than world harmony, which was the original goal for which the language had been created.

The idea of simplified spelling remained mostly dormant for the rest of the 20th century; however, recent developments might now make spelling reform relevant again. The first development is the smartphone, which seems to encourage experimental spelling, usually by removing as many letters as possible. Thus “Now is the time for all good men to come to the aid of their party” may be rendered, “Now S d tym 4 ll gud men 2 cum 2 d aid of their prT.”

Another development is the need for international communication in the global marketplace. Non-English speakers would welcome a spelling system that would enable them to pronounce written English so it could be understood. English isn’t the only language with this complication.

Jabbour hopes that parts of his phonetic alphabet might work their way into our language, allowing written and spoken English to resemble each other. It would be a great help in mastering our language—even if you already speak it.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now