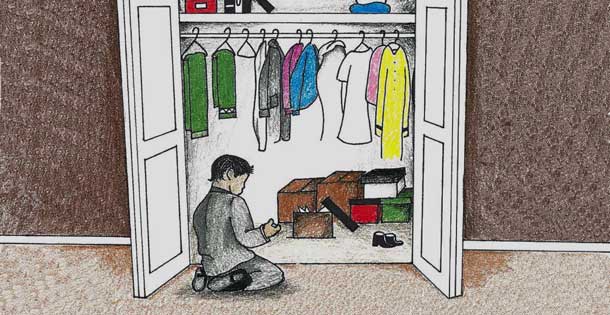

Ricky stumbled upon _____ while digging through a pile of shoeboxes in the back of his grandmother’s closet. Can you imagine? Just sitting there amongst old clothes, letters, books that might have been her most treasured possession. The line between the meaningful and meaningless was almost non-existent to the outsider, though, and without her around to give them life through memory, through experience, they reverted back to being garbage.

This was after the funeral, the awkward meetings, handshakes, lipstick scars from kisses on the cheek. You’re probably too young to remember me. You’ve became a little man! Ricky walked upstairs to get away, slipped into his grandma’s bedroom. Her bed was still unmade from when they found her in it, already gone. With the sheets torn open like that, it was almost like the bed itself was grieving. Ricky walked over, let his hand hover over the sheets, but couldn’t bring himself to touch the bed, afraid it might suck him in, take him with it.

Ricky brushed the dust off of _____, held it up to the window so he could see it better. His grandmother’s house was always dark. The deep brown walls and cramped rooms had a way of swallowing light, killing any warmth that dare enter.

_____ was just the way Ricky’s grandma had described it to him when he was little. This was shocking, coming from a woman who did nothing but tell Ricky incredible stories that were obviously fictitious to anyone but a child. She once told him about the time she and her best friend ran off to join the circus. Literally, she said that they joined a traveling circus. Apparently, the two girls started training for the tightrope walk before deciding they should just go back home. Another story involved the ghost of a little girl whom she would see dancing around a tree in her backyard. Her father had the tree cut down, and the girl never returned. Ricky’s grandmother had lots of stories about ghosts. But they were stories. Just stories.

Ricky held _____ close to his chest, hidden under his arms, like a wound, like a lesion he was ashamed of. He walked downstairs to where his relatives were talking, drinking, the whole house feeling somehow sing-song, the voices blended like they did at church, when everyone sang together, melodic despite the untrained voice, all on different notes. Unknowing eyes might think it was a birthday party, not a wake.

Ricky found his dad talking to his cousin, who’s name Ricky could not remember. He would later remember it (Anna) as she would begin making regular visits to see Ricky and his father. Ricky asked no questions, even after she drove his father’s car into a median on the highway, nicking a car coming the other way. His father was killed instantly, his chest crushed. The driver of other car was decapitated, and Anna got away with only a leg injury, and a limp that followed her for the rest of her life. Anna never even told Ricky she was sorry for killing his father. He felt that she wasn’t actually sorry at all. It didn’t matter, though, neither was Ricky.

“How are you holding up, buddy?” Anna asked, using the appropriate phrasing. You don’t ask people at funerals how they are, because they’re obviously not good. Or, at least that’s what they want everyone to believe. You have to ask it in a way that shows that you’re asking in relative terms. I know you’re not doing well, but in terms of how bad you could be feeling, how are you?

“I’m…I’m okay,” Ricky said. He motioned with his head, trying to dismiss Anna, but she didn’t leave, and in fact leaned in closer.

“What have you got there?” Ricky’ father asked, cocking his head to see around his son’s arms, not even considering that it might be something Ricky wanted to keep secret.

Ricky slowly uncurled his arms, letting ____ drop into his hands, like he was presenting it to his father as a gift, like he was one of the Magi in the nativity scene they use to put up during Christmas. Two white, one black, always.

“Oh, I see,” Ricky’ father said, looking over at Anna, who was smiling. Children, how amusingly naïve. “Did you get that from your grandmother’s room?”

It hadn’t occurred to Ricky until that moment that he might be doing something wrong, that he might be stealing, that somebody else could have already claimed _____.

“Yes,” Ricky said, turning his shoulder to the room, hoping to better hide his treasure.

“Well, it’s very interesting,” his father said, mockingly uninterested, not bothering to try and hide his lack of understanding.

Ricky looked up at his father, confused, certain he was playing a game. “But look. Grandma told me about it, she told me stories. I didn’t think it was real.” Ricky placed ____ into his father’s hands, realizing now how small it seemed when held by a grown man.

His father hefted _____ into the air, catching it bluntly, smiling, trying to appease Ricky, who had to use every bit of will he had to avoid snatching it back from his father. “It’s cool, Ricky. But it’s just _____. Your grandma has plenty of shit like this in that closet of hers.” He handed _____ to Ricky. “Now go put it back where you found it, and come straight back down. I have a few people I want to introduce to you before they have to leave.”

Ricky took _____ back, this time not being as careful to protect it, regretting letting his father touch it, letting his father know that it was important to him, letting his father make it meaningless with a few words. Ricky kept telling himself _____ was important, it was important, it was important, but it was already gone, crossed over into meaninglessness. Such a thin line.

Ricky put _____ back into the closet where he found it, stacked books and shoe boxes back on top of it, hoping no one would ever find, that it would remain there forever, like a fossil, perfectly preserved.

He knew he would never see _____ again.

Years later, after his dad’s accident–another funeral, another party for the departed–Ricky asked his aunt about ______. She had gotten his grandmother’s house, which caused Ricky’s father to hate her until the day he died. Just as well; he seemed to hate almost everyone.

“______?” she said. Attentive. Kind. Fake. “I don’t remember seeing it, but this house is full of that kind of thing. I’ll keep an eye out for it, okay?”

“No big deal,” Ricky said, “Dad had mentioned it a month ago, so I thought I’d ask.” He looked at his aunt’s eyes, her smile, glad to still be above ground, to still have lungs that could hold air, a little too pleased that her abusive brother had died so violently; the closed casket, rumors, whispered details.

Ricky looked at his hand, her lips, cheeks, quivering fingers, all convincing. But her eyes, they gave her away. He wanted to tell her that he was the one that had once cared about ______, not his father. The only person it hurt was Ricky, himself. But he didn’t say anything, just let her have her spiteful victory.

Ricky walked out the backdoor, through the kitchen into the backyard, passing family, friends, or perhaps people that hated his father and were hoping to get a chance to see his grotesque body. Ricky could hardly tell the difference. They all acted the same, spoke the same, were the same.

Ricky planned to leave through the backyard, but when he got there heremembered that there wasn’t a gate. There was no way to leave. He would have to make his way back through the house to the front door. He breathed in the air, wondering if was the same air he had breathed in when he visited as a kid. As he walked back into house, he noticed something in the backyard. A tree stump. He remembered his grandmother’s ghost stories, but in haste, drew no conclusions.

Later, Ricky would say that he knew that was the last time he’d see that house, that he planned on getting into his car and driving until he found something new, something better. That’s a debatable point, but the truth is that he never did see the house. Even after a gas line explosion wrecked most of the house and killed Ricky’s aunt, the last of her siblings, in the process.

Ricky, a thousand miles away, let the phone ring, listened to the messages left by one of his cousins, the details of the explosion, and then updates on his aunt’s condition; then the bad news, and then, finally, funeral plans. He never called back, didn’t even consider the idea of coming to the funeral. He only briefly considered returning a call once, when his cousin mentioned that they had found _____ among the wreckage of his grandmother’s house.

“Must be worth a fortune,” his cousin said, trying not to sound too excited, to get ahead of herself, overplay her hand. As if value is a thing that can be changed by a couple of words.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now