Chain, chain, chain, chain, chain, chain

Chain, chain chain, chain of fools.

— sung by Aretha Franklin

The showy, greased handlebar mustache and flashy biceps were unusual on a milkman, but otherwise everything looked kosher: the creaky black wagon with the word Cream painted in white script on the side, the large silver can jostling in the back. The horse was reined in at the service entrance to the Winchester Spirit House. The man shaded his eyes against the bright central California day and looked up and up and up at the never-ending mansion. He said later that it reminded him of an enormous gingerbread house from that fairy tale, gaily painted and vaguely Swiss-looking like that. He recollected the milk can, leapt off the seat, set his knees, and hefted the large silver canister onto the doorstep, mumble-swearing as he eased it down. Flourishing his cap theatrically, revealing a shiny bald head and a gold hoop in his left ear, he asked the servant who answered the door if she wanted him to haul the can into the house for her. She shook her head, said, “Nobody gets in here.” The man climbed back into the wagon, clicked his tongue at the horse. He said later that the place had given him the creepy-crawlies, and he was glad to see the back of it.

The can sat for several minutes in the late afternoon sun. Then servants came out, heaved it up, grumbling to each other, and hauled it into the house. Inside the can, up to his neck in milk, was Harry Houdini.

Please, I’ll explain. That year, 1915, I was covering the San Francisco World’s Fair for The Examiner, my first full-time job as a reporter. We’d been rocked and almost wrecked in 1906, so this celebration showed the world that everything in Frisco was copacetic again. I covered the fair right from the beginning, with headlines like “Wonder of Wonders” and “Heady Times These.” Alexander Graham Bell placed a cross-country phone call; Thomas Edison showed off his storage battery; Henry Ford created an automobile extravaganza. General Electric covered the exhibition in tiny lights; even the boats in the harbor twinkled. The centerpiece of the whole shebang was the Tower of Jewels. One of my stories detailed the 102,000 pieces of glittering multicolored cut Bohemian glass used in its construction.

The World’s Fair was the bee’s knees, as we used to say, but by November, as the fair was winding down, I was having to do a little digging to make my weekly deadline.

I reread the official brochure, and the last paragraph caught my eye: “Do you realize what this exposition means to you? This is the first time in the history of man the entire world is known and in intercommunication. In speaking of the earth, the qualification ‘the known world’ is no longer necessary.”

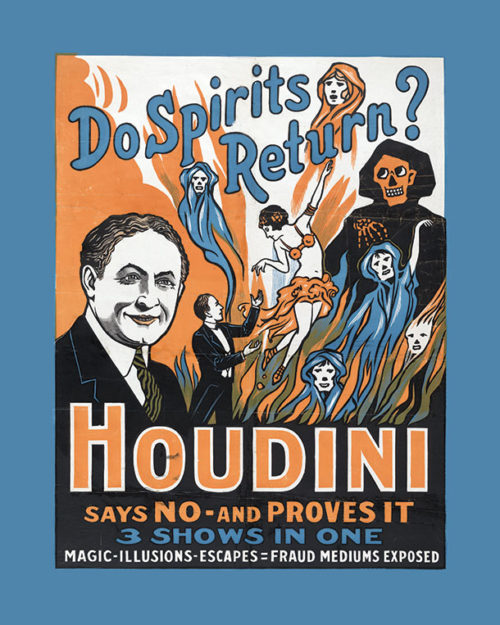

I was a man of knowledge myself, a member of the socialist party, voted for Eugene Debs, read Upton Sinclair. We believed the truth would set us free. But all the world could not be known quite yet — why then pursue knowledge? Plus, I’d be out of a job. Although so far I’d only written about the exposition, I wanted to be a muckraker like Fremont Older, eradicating humbug and skullduggery. I searched about for some unexplored murky corner of the Great Exposition to shine my light on. And then Houdini came to town.

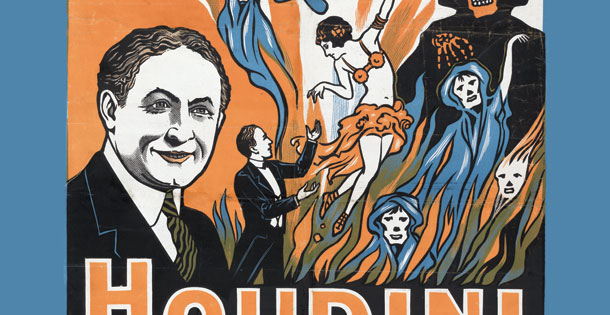

The King of Chains, the World Famous Self-Liberator, the Elusive American, the Prince of the Air, the Handcuff King, the Jail Breaker. He was a foreigner, and everyone loved him as if he were Yankee Doodle. First he had escaped Hungary, and then, perhaps even harder, he had escaped Appleton, Wisconsin. His father was a rabbi, but he seemed to have liberated himself from his religion, too. And even though he himself was a master of illusion, he worked to unmask the quacksters. He’d even written a book exposing the flimflam of the underworld. Why, he was our national inspiration.

I went to his show at the Orpheum. His dark hair was greased down and parted in the middle, his eyes made up like Sarah Bernhardt’s. He never smiled on stage, so he appeared to be glowering, in possession of mysteries the audience could not fathom. “Welcome, friends,” he began. His voice was deep and his accent slightly British. He hit those fricatives hard. His accent was just another thing he’d escaped.

He performed his world-famous Chinese Water Torture Cell Escape. It was a doozy, fully copyrighted, though I’m not sure what was Chinese about it. His feet were locked into what appeared to be a lid for a great tank of water. The sides of the tank were glass-plated, and inside was a metal cage. They lowered him upside down into the cage inside the tank. Then they locked the lid. His assistant, a bald, burly man with a gold hoop in his ear and a handlebar mustache, stood by with a sledgehammer in case he had to break in to save him from drowning. The curtains closed.

The seconds ticked by. The audience murmured nervously. While Houdini slowly ran out of air, I sat in my velvet-covered seat, holding my own breath and thinking about how I was like Houdini — like him, I’d erased my foreign accent, stopped going to Hebrew school, never went to shul, was taken for a real American. But I was also not like Houdini. I was 25 and still lived with my mother and sister. I had wanted to ride a motorbike across America that next summer, send articles from the road, but my mother had forbidden it — too dangerous, she’d said. I couldn’t hold my breath like Houdini, either. I had to take a gasp of air. I imagined the Great Escape from the Mother Embrace. A mother standing behind the King of Chains, her arms straitjacketing him, Houdini dislocating his own shoulders to free himself. And then I heard the applause start, looked up, and there he was — Houdini, bouncing around in front of the curtain, a free man.

At that very moment the idea came to me, like one of Mr. Ford’s motorcars straight off the assembly line, audacious and gleaming.

When I went backstage to interview Houdini, he was in a heavy floor-length maroon satin robe, untied. Underneath, he still wore his black bathing costume. His legs were hairless and extraordinarily developed. His muscular chest was also shaved, but his forearms gave him away as one of us — covered in wiry black hair just like my own. He was wiping off his eye makeup, which appeared to be greasepaint from the circus. His springy hair was already curling out of the brilliantine. He was a good-looking fellow, if you like the foreigner type, and I hope you do. He sort of hopped on his toes all the time, as if he had so much energy wound up in there he needed to continually let it out in those little hops. Some say the secret to his success was that he was double-jointed, but I think it was that energy — he was a 20th-century dynamo.

When he finished cleaning his face, he pulled an apple out of the pocket of his dressing gown, and began tossing it from hand to hand. His eyes crinkled, and he gave me an easy, pleased-with-himself grin — he had a space between his front teeth. “What can I do you for, bub?” he asked.

My own hands were clenched inside my pockets, something I’d trained myself to do so I didn’t gesture so much. After telling him his show was hunky-dory, I got straight down to business. I pulled him aside and unfolded my scheme. “Say, Mr. Houdini,” I began. In a town called San Jose, just a few hours’ distance from San Francisco, lived the old widow of the Winchester fortune. For 29 years she had been constantly building a house of crazy proportions, supposedly directed by ghosts.

Even from the outside you could tell something was strange. There were 13 stained-glass windows that had 13 panels fashioned in the shapes of spiderwebs. But no one except the servants could get into that house. They say the front door had never been unlocked. This house was the ultimate unknown. No one but the great Houdini could break in and shine a bright light on the hokum that surrounded it.

At first when I told him the scheme, he grinned his amused grin, said in his radio voice, “I’m an escapologist, bub, not a thief. It wouldn’t do for me to be caught breaking into someone’s home, especially a swank widow’s place. Why, I’ve written a book exposing the tricks of thieves. How would it do if I were marked as one myself? Why don’t I just call?” He hopped a bit on his toes, tossed his apple. “I’m sure the old bird would be amused by a call from Harry Houdini.”

I nixed that. I told him that Teddy Roosevelt himself had come to call and was sent away in a huff. While I talked he caught his apple in his mouth and began eating it. I told him I thought we could get worldwide coverage with a story like this. I knew publicity was Houdini’s bread and butter. In my enthusiasm I let my hands fly, outlining the headlines in the air: “‘The King of Chains Reveals Spirit House Is a Sham!’ The world needs to know,” I added.

He seemed to consider, munching thoughtfully. He said, “You say she is in communication with the dead?”

“That’s what they say,” I winked.

He tossed me the skinny core of the apple, sloughed off his dressing gown, and flipped into a handstand right in front of me. I looked down at him grinning up at me. “Is that a yes?” I asked, and he nodded. I slipped the core into my pocket, a souvenir. Two days later, there was Houdini, up to his neck in dairy inside the Winchester mansion. I’d suggested we use water, but Houdini had said milk was a more commodious solution. Sounds echoed strangely in the can. But finally, for seven minutes after he had been carried into the house, he heard nothing at all. Houdini was an expert at keeping time, an essential element of his act, as he later told me.

He popped the locked lid off, don’t ask me how. It fell onto the floor with a clang. He peeped up over the metal lip, his hair dripping milk.

A screech startled him.

A red-faced woman in a big, food-splattered apron, brandishing a wooden spoon, locked her predatory eyes with his for six seconds. Houdini was certain she had done the same with many hapless rats before him. Then she bum-rushed him. She sat down on the top of the can, trapping Houdini inside.

He heard the woman, who had an Irish accent, yell, “I’ve scared up a bogey in the milk.” Then there were a lot of voices. Someone clanged the side of the can, which hurt Houdini’s ears. She ordered some so-and-so named Lacy to fetch Mrs. Winchester. The cook announced loudly that the bogey was a dark devil from the Negro or Arab races. A male voice said, “Could be a genie that grants wishes.” The cook repeated that Lacy had gone to alert Mrs. Winchester. “I’m sure she already knows,” someone else said, and they all quieted down.

I must admit that at this juncture the great Houdini wanted out of the adventure. He was chilled and tired of being wet. He was hungry, as usual. Even more so, he sensed this scheme turning south — he knew what happened to intruders of the so-called darker races. “Meshuganah cup, shyster, donkey’s ass,” he cursed me in both Yiddish and English.

“It’s speaking!” someone said. “What language is that?”

“Arabian.” And there were general knockings on the can. For some reason, this tickled Houdini’s funny bone. He laughed and knocked back, then philosophically lapped up some of the milk he was bathing in.

Finally, after six more minutes, Houdini had enough. He positioned his palms on the considerable bottom. “It’s pinching me, it is!” the cook squealed. Houdini began to lift. There were some appreciative oohs and aahs as Houdini stood, shaking just a little, milk cascading off him, the squealing cook raised above his head. Even while she battered him about the head and shoulders with the wooden spoon, he said, “Allow me to introduce myself. I am Harry Houdini.”

The pummeling ceased. He was surrounded by a group of servants: the young woman Lacy, pointing a broom at him; two gardeners, one with a rake and another with a trowel; and a well-dressed old butler hefting a paperweight with a scene of the Alps as his weapon.

“That is the great magician himself. I’ve seen pictures,” said Lacy, lowering her broom.

“Ask him if he grants wishes,” said the man with the rake. “If we was to rub his tummy like.”

Then an ancient voice like chipped china said from behind them, “Kindly lower my cook, Mr. Houdini.”

Houdini brought the beefy woman back to earth. She straightened out her dress and apron, her cheeks aflame.

Free of the weight of the cook, Houdini bowed to an extremely short, veiled woman in a dark hobble dress. She looked like a well-appointed dwarf, thick like that, which made Houdini feel at home, as he’d had several dwarf colleagues when he worked at the Welsh Brothers Circus.

“What is the meaning of this intrusion?” the Widow Winchester asked.

“I’ve come to offer my assistance in your battle with the spirits, madam.”

“Please escort Mr. Houdini out.” And the snooty, miniature widow turned away.

The old butler holding the paperweight stepped forward. “Mr. Houdini, it would be my privilege —”

“Please, wait, Madam Winchester, I implore you,” cried Houdini. “Perhaps it is not you that needs help, but I. I am desperate to contact my dear, darling mother. I am dying with missing her. I never got to say goodbye.”

When Houdini told me this story, he was sitting on a green settee in front of a fire in his hotel room on the afternoon after the incident. He was in white silk pajamas eating a Jewish dish he’d asked the kitchen to prepare specially — sour cream with raw vegetables — Farmer’s Chop Suey. I was perched on an arm of the settee, taking notes. When he told me what he’d said about his mother, I grinned, remarked, “Quick thinking, Mr. Houdini. Did the widow buy it?”

He ignored me, continued to narrate in his deep radio voice between bites. I figured he did not care for interruption, and I tried to keep my mouth shut after that.

Mrs. Winchester looked up at him carefully through the veil. Then she had the butler take him away to be cleaned up in her indoor shower.

For some reason, the only attire they offered him was a Japanese kimono, obviously Mrs. Winchester’s — pink silk with a red dragon, very wide, but only reaching to his knees and elbows. He did not like to complain.

Then he was fed. Houdini sat in the kitchen in his kimono, Lacy and the cook waiting on him. He said that besides the roast, there was crab soup, caviar, and shrimps, which he declined due to his Jewish persuasion, then celery flan and orange fool for dessert. He praised each dish lavishly, and by the orange fool, the cook forgave him for hoisting her by her generous petard. She brought over a pot and three cups, and she, Lacy, and the great Houdini took tea together.

Lacy remarked that she was going to search out other employment. The money wasn’t worth it, she said, if her nerves were to be ruined. She couldn’t go about her job expecting a devil to pop out of a milk can or a phantom foot to emerge from the toilet and kick her in the arse or maybe a ghostly hand might pop out from under a chicken-fried steak.

“Don’t be a fool,” the cook said. “That warn’t no devil, it were Mr. Harry Houdini himself, and you’ll be telling your grandchildren you met him. And you make double the money here cash every day, so lamp along with you.”

Houdini inquired about the origin of the spirit problem in the house. The cook leaned in, whispered, “She’s most likely listening, she is; but since she let you stay, she wouldn’t mind me telling you that way back when she were a girl in New England, she married the Winchester heir, had a baby girl, and then husband and wee babe both upped and died on her. All mysterious it was. A spiritualist told her that her family be cursed by all the dead of the Winchester rifle, and if she didn’t commence to building a house right away, she were done for. In short, if she stops building, the spirits will kill her. And that’s all I’ll say on that subject.”

On they chatted cheerfully, Lacy and the cook trying to get Houdini to reveal the secrets of his escapes, and he trying to get them to reveal the secrets of the spirits, until at midnight a bell sounded all over the house. The two women grew silent. The veiled lady appeared at the door of the kitchen. She beckoned Houdini with a gloved hand.

At this point in the telling of the story, Houdini became agitated. He pushed aside his food, ran his hand through his thick, frizzy hair so that it stood on end. He hopped up from the settee and jumped onto his hands, walked around the hotel room on them, leapt back up. Finally he faced the fireplace, his back to me. “I spent two hours with Mrs. Winchester, and then she returned my bathing costume, freshly laundered, and my milk can emptied and cleaned as well. She graciously ordered round her car to take me back to my hotel. Unfortunately, I had to walk through the lobby in my bathing costume carrying the milk can at dawn. But no one seemed to mind.”

He picked up an iron poker and fenced with it. “The end.”

“The end?” I said.

“More or less.” He continued to vigorously fence his invisible opponent.

“But. You haven’t even described the house. What did you do with her for two long hours?” I shook the writing tablet that I’d been furiously taking notes in. “Finish the story, sir. I implore you.”

He dropped the poker and went back to standing on his hands. “I prefer not to.”

“Please, Mr. Houdini. I need to know.” I didn’t add that I had a deadline to make.

He was still upside down. “If I tell you, you must swear not to write about it.” He balanced on one arm and held his hand out for my notebook.

I had a decision to make, and fast, because I surmised that if he stood up, our conversation would be at an end. Here I must admit I decided that if the story were really good, I would publish it anyway. I had a memory for details. He was balancing on both hands again, so I gently pressed the notebook between his teeth.

He righted himself, spit the little notebook into the fire, reseated himself on the settee, scraped up the last of the sour cream, cleared his throat, and continued. “The house. Labyrinthine. Outrageous. Stairs ending at the ceiling. A stairwell leading to a door that opened onto a wall. A window to another part of the house. An entire wing seemed to be blocked off.” He said there must have been hundreds of rooms, all with the finest decorations, all eerily empty of inhabitants.

Strangest to him was the stairwell that Mrs. Winchester slowly led him up. It was narrow, wound round and round, and had a rise between each stair of no more than an inch and a half, with a railing just a couple feet off the stairs. Perfect for a miniature widow with joint pain.

At what seemed to be the very center of the house, Mrs. Winchester stopped in front of a pale green door. She gave Houdini the once-over again, and then she knocked her cane against his shin, smartly, twice. Making sure he was solid, most likely, he said, and not a spirit got up to look like him. I laughed when he told me that, but he was not in a laughing mood. He’d thrown himself across his bed by this point, flung his arm over his eyes.

Mrs. Winchester nodded and turned and he followed her in. She sat herself down in the small room that contained a table with two chairs, nothing more. The chairs were regular sized, and her feet did not touch the floor, but she had a small velvet-covered stool to rest her feet on. She unveiled herself.

She had a round, jowly face, a lot of gray hair piled on top of her head, a large bosom for one so small, and, Houdini said, very small eyes. She had in front of her one of those children’s novelties, a Ouija board.

Houdini sat down in the other chair.

“You may quietly observe,” she said. “I have most important business to attend.”

“May I inquire about the nature of this business, madam?”

“I must consult the spirits about an addition to the house they lately specified.”

“But why do they insist on this endless production?”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t know?”

“I suppose they are bored. Maybe they like to see their plans come to fruition. I know it comforts them.”

“But do you not long to be free of them? I am, forgoing modesty, the greatest escapologist in the world. Perhaps I can assist in your release.”

“And then what should I do?”

Mr. Houdini was a bit at a loss, not being an expert in how rich old ladies spent their time. “Go to the theater?” he ventured. “Give money to charitable institutions? Paint teacups?”

Mrs. Winchester rolled her eyes. “I must begin. It is a laborious process of communication, and I only have two hours.”

“Madness,” I remarked to Houdini.

“Didn’t you demand to know the point of all this useless construction?”

“How could I, when I have dedicated my life to locking myself up and freeing myself for people’s amusement?”

“Can you help me first?” Houdini asked Mrs. Winchester. “I want to speak to my dearest Mamala.”

“Was she killed by a Winchester rifle?” Mrs. Winchester asked.

“She died of a stomach problem, they say, while I was abroad. I never got to say goodbye. But can’t you ask your friends to rummage around for her?”

“They are not my friends,” Mrs. Winchester said. But she asked out loud, “Can you locate Mr. Houdini’s mother?” Then she sat patiently, her fingers lightly touching the planchette, which was wooden and shaped like a heart with a hole at its center. The planchette moved slowly over the board to the word yes.

“How is she?” Houdini said eagerly. “Tell her I love her. Tell her I miss her.”

“Slow down, slow down,” Mrs. Winchester grumbled. She asked, “How is she?”

The planchette was still, then moved over the no, then spelled out english.

“What does that mean?” Houdini asked.

“They can’t understand her. She’s speaking in a foreign tongue.”

“Hasn’t any Jew ever been killed by a Winchester rifle? Tell them to tell her to speak English.”

She said, “Tell her to speak English.” Mrs. Winchester slowly spelled out: what with the shmate?

“Oh.” Houdini looked down at his kimono. “A shmate is a rag.”

“That’s imported Japanese silk,” Mrs. Winchester said. “I need to get to work. They only convene between midnight and 2 a.m. When I’m done, if there’s time, you can speak to your impertinent mother again.”

Mrs. Winchester asked architectural questions aloud, then the Ouija board spelled out the answers. She took notes on a gray tablet with a pencil. Sometimes she argued or asked the Ouija board to be more specific.

Houdini observed politely for 37 minutes. Then he began to crack his neck and fingers, later his toes. He amused himself by doing stretches and calisthenics. Push-ups, sit-ups. He practiced his handstands, then his handstands on one arm. He stretched his head between his legs. He managed a one-armed handstand on the chair.

The Widow Winchester was completely absorbed, not interested in the slightest that the great Harry Houdini was giving her a one-man show. For his part, he declared that watching the old woman work the Ouija board for an hour and 15 minutes was the most boring performance he had ever witnessed.

Finally, he put his head down on the table. Did he fall asleep? He wasn’t sure. He closed his eyes, and when he opened them the room was crowded with the dead. He was absolutely sure they were dead, right away — not because they were vaporous, which they were not; and not even because they floated a little off the ground, just enough so that you could have slid a piece of paper underneath, which they did; and not because they moved about by exhaling a cold, dank breath that propelled them this way and that, according to the way they angled their chins, which they also did — but because they all had terrible gunshot wounds.

Half a face shattered to the bone, the back of the head blasted away, a burst of red on a waistcoat, an arm dangling, useless. They were not active wounds, there was no blood leakage, but they were forever unhealed and disconcerting nonetheless. It was loud in there, too, because they were all arguing with each other and with Mrs. Winchester about their joint building project.

And then, pressed into a corner, Houdini spied a bony-faced old lady with a wisp of a gray topknot wearing a long white nightgown. It was his darling Mama Weisz. Houdini shouldered his way through the busy, grisly group until he reached his little mama. They embraced, held hands; he wept; she stroked his face. By his calculation, factoring in his possible nap, they only had approximately 33 minutes together.

She inquired about his health and about his wife, Bess, but mostly she wanted to talk about food. She told him that was what she missed most — eating. They reminisced about shmaltz herring, kreplach, borscht, fried chicken hearts, pupiks. He grinned at me. “She had such a yen for Farmer’s Chop Suey, it was infectious.

“How I miss her cooking,” he said. “Which is funny, because she really wasn’t a very good cook. Her matzo balls were rocks. Her chicken soup tasted like maybe some hot water that a chicken had rested in for a minute or two before flying on to more important matters.”

They were pressed close by the animated, arguing crowd, whispering to each other. Mama Weisz said Houdini’s breath smelled sweetly of orange zest with a fresh hint of celery. She said the breath of everyone where she was smelled like nothing, or like mud, and anyway breath was used exclusively for locomotion on the other side.

“But Mama, how is it? This afterlife? Is it paradise?”

“It could be worse,” Mama Weisz replied, “but there’s high unemployment, about 100 percent. That’s why these schmucks are so excited.”

“That was when she asked me to breathe on her face,” Houdini said, his voice no longer sounding so British. “We held our hands together, and I breathed, and she closed her papery eyelids and opened her mouth to take in my breath, and she said things like ‘ah’ and ‘warm’ and ‘salty’ and ‘tart’ and then the next thing I knew the bell rang, and I was standing in that corner by myself.” Mr. Houdini lay on the bed with his hands covering his eyes, quiet and still.

“But what then?” I asked.

“Mrs. Winchester slid off her chair and unlocked the door of her séance room. The butler was standing there. ‘Please show Mr. Houdini out,’ she said.” The last thing she’d said to Houdini was “I will make sure my milk is inspected from now on.”

“I was so overcome with my experience, I said nothing,” Houdini whispered. “I didn’t thank her. I didn’t ask to return.”

I felt overcome myself. I sat down on the side of the bed. “But, Mr. Houdini, what do you think really happened? Do you think you were drugged? Do you think she mesmerized you in some manner?”

“I don’t know,” he said, “but it was the most important experience of my life.”

To be honest, the whole narrative unnerved me. There seemed no way to uncover the truth. I don’t remember our leave-taking. That week I turned in a piece about the elaborate plans to ship the Liberty Bell back to Philadel- phia after the exposition. I never told Houdini’s story, and for years I put it out of my mind.

The headline for the next 40 years of my life could have been “Heady Times These.” I got married, had three little girls, and my sister and mother lived with us, too. I never rode a motorbike cross-country, but in the ’20s I investigated corruption in the San Francisco mayor’s office and in railroad regulation. In the ’30s I uncovered the plight of the Dust Bowl immigrants; in the ’40s I wrote about imprisoned conscientious objectors; and in the ’50s about the 31 University of California professors fired for not signing anticommunist loyalty oaths.

My mother died in ’38, my sister in ’45. One daughter lives in Paris now with the grandchildren, the other two are singletons in LA. When my wife passed away of the cancer in 1960, I retired to Delray Beach, Florida. Eight years I’ve been here now.

In my senior residence we have the shuffleboard, we have B’nai B’rith. The big sport is playing bumper cars in our Lincoln Continentals to nab the spot closest to the entrance of the restaurant in time for the early-bird special. I like watching The Smothers Brothers; I listen to Aretha Franklin on my record player; and I send money to plant trees in Israel in the names of all my dead relatives. But mostly, I finally have time to look back, turn it all over in my mind — cogitate, so to speak.

For example, I wonder what Houdini would have thought about World War II, about the 6 million of our people who never escaped. Or what Mrs. Winchester would have to say about the millions killed by the M1 produced by the very same Winchester corporation. Imagine how crowded that séance room would be now, how endless that mansion.

As far as I know, Houdini only returned to the Winchester Spirit House one more time, after Sarah Winchester died in her sleep. In 1924 Houdini got himself invited on a tour of the mansion at midnight, but nothing happened — at least that’s what he told the newspapers. In the article he sounded bitter. Houdini himself died in 1926 of a burst appendix. His last request, so they say, was to order out for Farmer’s Chop Suey.

That last request makes me wonder about my own mother, and the mysteries of mothers in general. How did she conjure that endless love for me? What would it be like to be in that séance room, so the Widow Winchester could bring my mother to me, and my sister, and my darling wife, even if just for 33 minutes.

But so far I’ve had no ghostly visitations from my beloveds. Even Houdini and Mrs. Winchester have been silent.

Still, no one was silent back then. What energy we had! What verve! I thought we were so different — I searching for the truth, they trying to escape it. But the truth is, we’re all the same: me, Houdini, Mrs. Winchester — even these young people I see on television, burning their draft cards and their bras and dancing like meshugas to that meshuga music.

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the 20th century! Take a seat. You will observe such wonders! Mercurial escapes, absurd and endless construction, utopian dreams, outrageous savagery! Wait, we still have some tricks up our sleeve.

Please, don’t go.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now