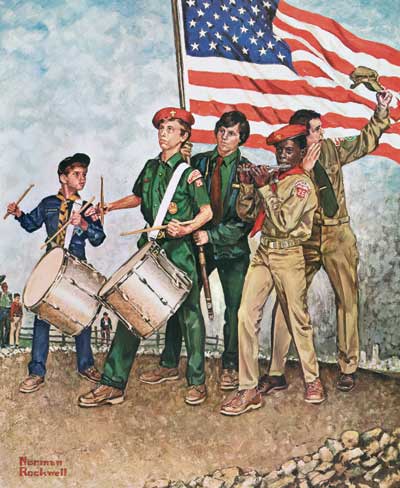

© Brown & Bigelow, Inc., St. Paul, Minnesota/Courtesy Boy Scouts of America

I was 10 years old when Dad made me jump into the station wagon with a bunch of Boy Scouts for a five-hour trip from New Jersey to Norman Rockwell’s studio in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

I didn’t want to go.

When we arrived, there was half an inch of snow on the ground. So I looked for pigeon-toed footprints in the snow leading to the red carriage house studio — having heard the story of the artist’s famously awkward feet — and found them.

Inside, I marveled at the African masks and spears on the walls and the replica of Ben Franklin’s printing press. On his easel sat a large horizontal painting of Abraham Lincoln having his photograph taken. On a low shelf, I saw a skull wearing a German spiked helmet. Springs attached to the jaw made it snap shut when you spread it.

Dad told me to stop touching stuff.

Rockwell and photographer Louie Lamone arranged the Scouts and Scoutmaster, my uncle Byron, in a line as if marching in a parade. My cousin Byron, in Scout uniform, carried a drum. An older boy held an American flag on a pole.

“It needs to fly,” Rockwell said as he tied a string to the top corner of the flag and turned to me. “Jeff, take this and climb up to the loft,” he said, sounding as if he had marbles in his mouth. I obeyed. It was hot up there. The flag rose in the simulated wind and the shot was snapped.

Rockwell gave me a check for $25 for the job. I cashed it when I got home and bought a Joe Namath football. The football’s long gone, but Dad was wise to make a copy of the check, which I now have framed, proof of the tiny role I played in Norman Rockwell’s last Boy Scout painting.

—

To read more about the author’s father, artist Joseph Csatari, read “The Illustrator’s Apprentice.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now