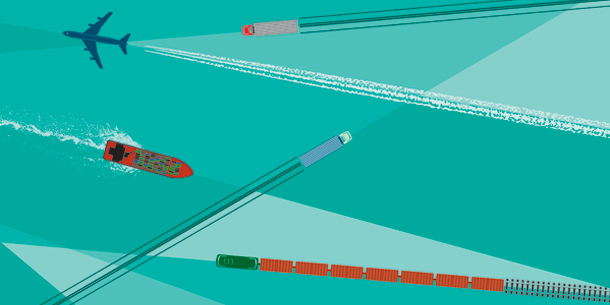

More than smartphones, more than television, more than food, culture, or commerce, more even than Twitter or Facebook, transportation permeates our daily existence. In ways both glaringly obvious and deeply hidden, thousands, even millions of miles are embedded in everything we do and touch — not just every trip we take, but every click we make, every purchase, every meal, every sip of water and drop of gasoline. We are the door-to-door nation. What does it take to keep America moving — to keep our cars and trucks on the road, our store shelves stocked, our cupboards and sock drawers, gas tanks and coffeepots full? Like an iceberg, impressive on the surface but with far more obscured below, the machinery of movement grinds away, a heady blend of miracles and madness that enables Americans to drive 344 million miles every hour and move $55 billion worth of goods every day (which, by way of comparison, is triple the daily income of every household in America combined). Look anywhere in the modern American home and you will see necessities, ordinary items — things we use every day — whose journeys to us make Marco Polo’s voyages pale by comparison.

So what does this look like under the hood, this vast system that takes us and our stuff door to door day in and day out? What does it truly cost us, and what can we afford moving forward? Are the wheels spinning better than ever, or are they about to come off the rails? Or is it a bit of both?

Consider the hidden world of Angels Gate, the hilltop vantage point in Los Angeles overlooking North America’s two leading, constantly bustling side-by-side seaports awash with cargo aboard ships the size of city blocks. There you can find a single mother of four by the name of Debbie Chavez, author of the daily “Master Queuing List,” with which she quite literally holds the lion’s share of the U.S. consumer economy in her hands. Angels Gate is where America’s commute truly begins, aboard ships piled 15 stories high with cargo containers, each far safer than your car and each hauling enough products to stock five Costco warehouse stores. On any given day, 50 such vessels are lingering at the dual ports, with a couple dozen more waiting in line for space at the docks, waiting for a spot on Debbie Chavez’s list.

Then there are the steely-nerved port pilots who live (and risk death) by that list as they guide the towering ships past Angels Gate and up to the biggest docks in America. With the skill of surgeons they squeeze these mega-ships beneath bridges with just a few feet of clearance and down narrow channels intended for the smaller vessels of a bygone age — an exercise in titanic parallel parking not for the fainthearted. Wonder and madness, the new and the old, are constantly battling in the door-to-door maelstrom.

Consider the vast corporate flotilla that rules the seas without a single gun, cannon, or missile. All that fleet does is carry 15 percent of the world’s goods. And through its alliance with the number two shipping line, it controls a third of the world’s products.

Finally, there is the sheer crazy wonder of it all. The capacity to transport a supercomputer, a desperately needed medicine, or a tube of toothpaste from a factory in Shanghai to a store in Southern California or New Jersey or Duluth — and to do so 20 billion times a day reliably, affordably, quickly, and trackably — may well be humanity’s most towering achievement. And yet it is accomplished with so little fanfare it’s virtually hidden from public view. Every time you visit the website for UPS or Amazon or Apple and instantly learn where in the world your product or package can be found and when it will thump on your doorstep, you have achieved something that all but the still-living generations of humanity would have declared impossible or demonic.

Consider the travels of that humblest yet most vital elixir: the morning cup of coffee. Costco French Roast consists of a blend of beans from South America, Africa, and Asia, each component shipped by container vessel up to 11,000 miles in 132-pound loosely woven sacks of raw, green coffee beans, some across the Pacific Ocean to ports up and down the West Coast, the rest via the Panama Canal, perhaps the Suez Canal, then on to one of several East Coast ports. The complexities are so great on this routing — based on ship space, season, and the vagaries of rates and departures — that it’s difficult to trace bulk products more precisely than this. The raw beans then travel by freight train or truck (2,226 miles for the Port of Los Angeles portion) to one of the world’s largest blending and roasting plants, located at 3000 Espresso Way in York, Pennsylvania, one of six such plants in the Starbucks empire and the one identified by the company as principally serving Costco. After roasting, blending, and testing to make sure every batch smells and tastes exactly the same no matter how many times a customer buys Costco French Roast, the beans are sealed in plastic and foil composite bags with their own coast-to-coast mileage footprint. Then the packages are stacked on wooden pallets (sourced from all over the nation) and shipped another 2,773 miles back across the country to the Costco depot in Tracy, California, from which my coffee was trucked to my local Costco store. By the time I got those beans, they had traveled more than 30,000 miles from field to exporter to port to factory to distribution center to store to my house — more than enough to circumnavigate the globe.

But that’s not where the coffee mileage stops. There are the components of my German-built, globally sourced coffeemaker, which collectively traveled another 15,700 miles to reach my kitchen. The drinking water I use to brew my coffee comes to my home from a blend of three sources: from groundwater pumped in from local wells about 50 miles distant; via the 242-mile Colorado River Aqueduct; and through the 444-mile California Aqueduct, which moves water south from Northern California, forces it 2,000 feet straight up and over the Tehachapi Mountains, then down into Southern California. The fuel and energy required for this third leg exceeds the electricity demand of the entire city of Las Vegas and all its glittering casinos. The electricity that powers my coffee machine runs through a grid festooned with millions of transformers and capacitors, most of which are now imported across 12,000 miles from China through the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, a complex that is a veritable city unto itself. The natural gas that fuels the power plants that provide most of the electricity to my coffeemaker is obtained from gas fields in Canada and Texas and sometimes farther through a 44,000-mile network of underground pipelines — part of North America’s hidden energy transport plumbing.

cup of coffee is hovering at 100,000 miles minimum. And that’s not counting the seemingly smallest segment of that journey, my 6.3-mile drive to Costco in my 2009 Toyota Scion xB, which has the most massive transportation footprint of anything I own — and not because I drive it very far. The Scion was built in Japan out of about 30,000 globally sourced components from throughout Asia and Europe, with one U.S. manufacturer contributing: The tires are from Ohio-based Goodyear, which has factories in Asia as well as the U.S. The assembled car was shipped from Japan to the Port of Long Beach in California, then trucked to a dealership in Southern California (other cars arriving by ship move by train to more distant dealers). The cumulative travels of the raw materials and parts of my car totaled at least 500,000 miles before its first test drive. The gas in its tank is a petroleum cocktail that adds another 100,000 miles to the calculation, as the California fuel mix consists of crude oil from 14 foreign countries and four states. Most of this oil arrives by tanker ships at West Coast ports, then moves thousands of miles around the state and country to tank farms, refineries, fuel depots, and distribution centers via pipelines, railroads, canals, and semi trucks before finally appearing at my neighborhood gas station.

Thousands of man-hours and billions of dollars in technology and infrastructure — along with the efforts of countless unsung heroes who pack, lift, load, drive, and track it all — combined to bring that cup of coffee to my lips.

That cup of coffee is a modern miracle, magical and mundane at the same time, though we hardly if ever notice the immense door-to-door machine ticking away, making it happen with product after product, millions of them, each requiring the same level of effort and movement, day after day.

We live like no other civilization in history, embedding ever greater amounts of miles within our goods and lives as a means of making everyday products and services seemingly more efficient and affordable. In the past, distance meant the opposite: added cost, added risk, added uncertainty. It’s as if we are defying gravity.

The logistics involved in just one day of global goods movement dwarfs the Normandy invasion and the Apollo moon missions combined. The grand ballet in which we move ourselves and our stuff from door to door is equivalent to building the Great Pyramid, the Hoover Dam, and the Empire State Building all in a day. Every day. It is almost a misnomer to call this a transportation “system.” Moving door to door requires a complex system built of many systems, separate and codependent, yet in competition with one another for resources and customers — an orchestra of sometimes harmonizing, sometimes clashing wheels, rails, roads, wings, pipelines, and sea lanes.

And yet the same conductors of this magical door-to-door symphony also leave us with grinding commutes: Angelenos spent an average of 80 hours a year stuck in traffic in 2014, while New Yorkers bore a “mere” 74 hours of traffic-jam penance. They gift us with more than 35,500 annual traffic fatalities — one death every 15 minutes. And we are the proud owners of roads we can no longer afford to maintain, saddling the country with an impossible $3.6 trillion backlog in repairs and improvements to aging roads and bridges — a deficit that grows every year, because Congress has refused to raise the 18.4-cent-per-gallon federal fuel tax. It’s been frozen in place since 1993 without even adjustments for inflation (which means that 18.4 cents is now worth only 11.2 cents). Drivers now pay barely half the cost of maintaining the highway system through gas taxes, with the rest subsidized. Meanwhile, more than 61,000 of our bridges are officially designated “structurally deficient.” There is no money to fix most of them.

How can a country that deploys insanely capable robot rovers to Mars and puts unerring GPS chips in our pockets leave us with two-ton rolling metal boxes to transport one person to work each day — boxes that kill 97 of us every day and injure another eight every minute? Cars are the American family’s largest expense after dwellings. But the typical car sits idle 22 hours a day, for which privileged Americans, on average, pay $1,049 a month in fuel, ownership, and operating expenses.

Miraculous and maddening — these are the two poles of our transportation system, inside which Americans spend an unimaginable 175 billion minutes a year, at an equally unimaginable annual cost in money and time of $5 trillion. An estimated $124 billion of that cost consists of lost productivity due to traffic jams, projected to rise 50 percent by the year 2030.

These two faces of transit are often viewed and treated as two separate, even competing worlds — the frequently frustrating, in-your-face reality of how we move ourselves, and the largely hidden world of goods movement with its gated marine terminals, secure distribution centers, and mile-long trains. The same Los Angeles–area communities that embraced a billion-dollar bill to add a lane to Interstate 405 have successfully fought off for 50 years the completion of another north-south freeway that would connect the port to inland California with its vast web of warehouses, distribution centers, and shipping terminals. Residents oppose the building of the last five miles of this freeway, Interstate 710, because it is seen as benefiting freight, not people, as if the local Walmart stocked itself. The stream of big rigs flowing from the port instead have to take roundabout and inefficient routes on other freeways, wasting fuel and time — and adding to commuter traffic jams as well, where drivers curse the ponderous big trucks they have inflicted on themselves.

Perceptions aside, there are no separate transportation systems, just one, sharing the same crumbling, underfunded infrastructure, the same limitations of cost, energy, and environment. They are two limbs on a single tree, mutually dependent, both grappling with potential disruption from old problems and new technologies. The idea that goods and people can be considered separately from one another when it comes to building roads or enlarging ports or creating supply chains is one of our primary transportation obstacles and myths.

The hidden side of our commute, the flow of goods, has become so huge that our ports, rails, and roads can no longer handle the load. They desperately need investments of public capital that the nation does not seem to have. Yet it’s an investment that must be made, as logistics — the transport of goods — is now a vital pillar of the U.S. economy. Goods movement now provides a greater source of job growth than making the stuff being shipped.

“Your kids will never go hungry if they have degrees in global logistics,” says the head of UPS for the American West. “But we have to leave them a transportation system that works.”

At the same time, new manufacturing technologies — the science fiction turned fact that is 3-D printing — are pushing in the opposition direction. This “unicorn” technology gives businesses in Brooklyn, Boston, and Burbank the power to manufacture a fantastic range of products — from surgical implants to car parts to guns — and to do it cheaper than a Chinese factory connected to American consumers by a 12,000-mile supply chain. New local businesses are emerging almost daily, stealing manufacturing from offshore factories and the eyes of Angels Gate. It’s just a commercial trickle, this “re-shoring” of offshore manufacturing, not enough even to register statistically, much less hurt the business of ports and shippers — for now.

These countervailing trends have the power to upend our brilliant and terrible global flow of goods and people, not in some misty, speculative future, but in a very few years. Which means our transportation-immersed door-to-door world and every aspect of it — culture, food, economy, energy, environment, jobs, climate, your cup of coffee in the morning — is at a very large, very vital fork in the road.

As one of the nation’s leading transportation scholars, authors, and bloggers, David Levinson of the University of Minnesota sees it: “We’ve been slow to change. But change is coming.”

Buckle up.

Edward Humes is the author of 10 critically acclaimed nonfiction books, including the bestseller Mississippi Mud. Humes has received the Pulitzer Prize for his journalism and numerous awards for his books. He has written for The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Magazine, and Sierra. He lives in California.

This selection is from the book Door to Door: The Magnificent, Maddening, Mysterious World of Transportation by Edward Humes. Copyright © 2016 by Edward Humes. Reprinted by permission of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

This article is featured in the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now