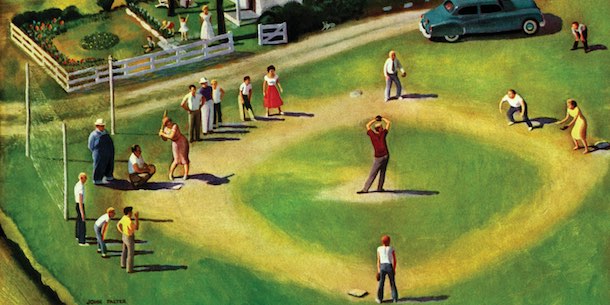

John Falter

September 2, 1950

This article and other features about baseball can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, Baseball: The Glory Years. This edition can be ordered here.

Few people have a stronger grip on baseball’s history and its roots in American culture than Ken Burns.

His love of the game was kindled in childhood while playing in the PONY and Little Leagues in Newark, and in his award-winning documentaries Baseball (1994) and The 10th Inning (2010), he explored America’s development through the prism of our national pastime. As he told us, “If you really wanted to know over the whole arc of American history who we were, there was no better metaphor, or past to follow, than the story of baseball.”

In one form or another, Americans have played baseball since the early 19th century. The game has continued uninterrupted (except briefly by strikes) through world wars, labor struggles, the upheaval of the civil rights movement, the rise and fall of cities, and much more.

But where does the game go from here? West Coast Editor Jeannie Wolf, who interviewed Ken Burns for the March/April 2014 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, went back to the filmmaker to ask for his thoughts about the game, its staying power, and how it might change in years to come.

Jeannie Wolf: Let’s start with the present. What do you see as the current state of baseball in America?

Ken Burns: Baseball is in as good shape as it has ever been. It has weathered the great crisis of its labor disputes of the 1990s and the even greater steroid crisis of the 2000s. Commissioner Bud Selig – who is retiring in 2015 – is leaving the game in a very solid place.

But baseball’s no longer the sole national pastime, because there are so many other sports and forms of entertainment. That doesn’t mean that the game’s not central though. When something happens in baseball, we care about it more than we do other sports. I’ll give you an example. When steroids became a problem in Major League Baseball, the news hit the front page of The New York Times — the paper of record. When Bill Romanowski, an NFL linebacker, was charged with using steroids, that was a sports-page story.

What I think is so interesting about base- ball is that it’s viewed as an embodiment of the American ideal yet involves stealing, cheating, labor disputes, racial struggles. Baseball in many ways leads America — in dealing with racial issues, immigrants, labor, and popular culture. It’s a mirror of our times.

Baseball is still the bellwether of our republic, the canary in the coal mine. If baseball is sick, America is sick. But baseball is very healthy right now.

J.F. Kernan

May 28, 1932

JW: With the rapid pace of change today, how will baseball change and evolve?

KB: Besides the Constitution, very few things in this country stay the same. The look of the game may change — they’re always trying to jazz stuff up, more often than not with terrible effect. he uniforms we admire most are ones that barely change. And the ones that we cringe at are ones with the garish colors and strange designs. But they’ll keep fooling around with it. They always have. If you asked me the same question in 1914, I’d give you the same answer. At the time, they were building new stadiums – beautiful new steel stadiums unlike the wood ones that were susceptible to fire – just like we’re building these retro ballparks now that don’t look like the ugly, suburban ballparks they got rid of in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and all across the country. But as I said, that’s just the look of things, and doesn’t affect the game.

In the future, I think they will fiddle around with rules to try to speed the game up. But the game’s always had a stately pace, and it’s a mistake to try to become what you’re not. Baseball is the only game in which the defense has the ball. It’s the only game in which you don’t run up and down the rink or the field or the gridiron. You’re on a diamond. You’re in a park. You’re running around the bases. What’s the ultimate object? To come home! It’s a timeless game. There’s no clock. We should play to the strengths of baseball, and I think we will.

For all the superficial changes, I predict the game will stay the same. A .300 hitter means the same thing to my daughters as it does to me as it did to my father and my grandfather and my great-great-grandfather who fought in the Civil War. There is almost nothing in American life that you can say that about. If a .300 hitter stays the same 25 years from now – which I guarantee it will – that’s something.

That is the kind of continuity that hearkens back to the timeless images of Norman Rockwell. It’s comforting. That’s what home is about and that’s the object of this game — to come home. That’s what – in a metaphorical sense — is what we all yearn for, a sense of belonging and place. Baseball can be wildly experimental and has had its issues with labor and drugs. All the things that affect modern society are there in microcosm in baseball. But at the end of the day, the game also reminds us of the timeless virtues that we all subscribe to.

Harvey Kidder

January 1, 1955

JW: Are kids playing the game like they used to, practicing in backyards or school stadiums with dreams of making it into the big leagues?

KB: Kids today may not play the game the way they were when I was growing up and certainly not the way they were when my dad was growing up. There’s less pickup ball, less sandlot ball. It’s all organized league ball, but we still seem to grow the same number of talented players.

JW: Where will players come from?

KB: The play on the field is as good, if not better, than it has ever been. And we’re seeing great players coming into the game from the Dominican Republic, Korea, or Japan. Of course, there are still plenty from Pennsylvania, Southern California, or Arizona. There are still many guys who look like they’ve come right out of a cornfield in middle-America throwing 100-mile-an-hour fastballs, as well as guys who routinely hit the ball out of the park.

But for all these homegrown players, the game will constantly mirror immigration patterns of the United States. Who are the biggest immigrant groups? Asians and Hispanics. If you asked me this question 100 years ago, we’d be talking about the influx of central and southern Europeans who were just then beginning to dominate baseball. Baseball has been a mirror of America since its inception, and it always will be.

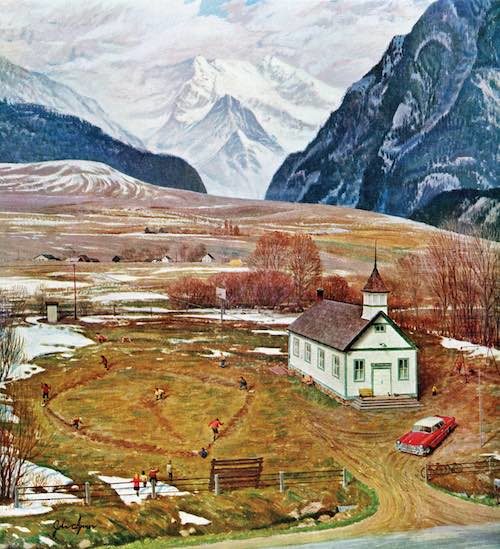

John Clymer

April 2, 1960

JW: What about the fans? Do you see fandom changing over time?

KB: Baseball will always be a game handed down intimately. When you tell stories about a football game, you don’t say, “My mom and my dad took me.” You just say what happened on the field. But when talking about baseball, the story always begins with, “My mom took me to this game…” or “My dad took me to this game …” and then they describe the action. Baseball’s very much a sport tied up with its own history.

Statistics don’t mean nearly as much in basketball or football as they do in baseball. I can say to an average citizen, “714,” and they know that that’s the number of home runs Babe Ruth hit. I can say, “755,” and they know that that’s the number that Hank Aaron hit. I can say ,“406,” and they think, That’s what Ted Williams batted in 1941. I can say “56” and they’d say, “That’s the number of straight games that Joe DiMaggio hit – also in 1941.” I can say the number 42, and they say, “That’s Jackie Robinson’s jersey number that was retired by every team in every ballpark in tribute to the first African-American to play in the major leagues.” Statistics matter. But if I ask, “How many passing yards does the greatest running back have?” People don’t know, and it doesn’t matter as much.

Baseball’s a game very much tied to time, and that’s why we’ll keep creating new fans. There will always be people like me – a father of four daughters who takes his girls to the ballpark. I have the two grown girls, and they are full- edged baseball fans. And I’ve got two little girls, 9 and 3, and I take them to the ball game. I caught a foul ball the last time I took them to a game, and I handed it to my then 8-year-old — and my then 2-year-old looked at me and said, “I want a baseball, too.” We managed to get some guy to buy a baseball then hand it to her, so she was happy about that.

Harrison McCreary

September 7, 1929

JW: Are we also making concession to concession, giving up our stadium favorites in a nod to healthier fare?

KB: Baseball has made a concession to modern appetites and tastes, but I don’t concede anything to concessions. Besides on the Fourth of July, the only time I have a hot dog is when I go to a ballpark where I’ll definitely order one. A hotdog never tastes as good as it does at the ballpark. Give me my peanuts and Cracker Jacks, and I don’t care if I never get back!

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now