Of all the industries shaken and destroyed by the fast-paced development of technology, one would assume board games to be sunk by their video counterparts. In reality, “tabletop gaming” is in the midst of a golden age. According to The Guardian, sales of board games is rising 25% to 40% each year.

Millennials aren’t necessarily playing Parcheesi, though. The new wave of games includes titles like Secret Hitler, Ex Libris, Dragonfire, and Pandemic. On the rise are role-playing games, connection games, Eurogames, and, sometimes, analog versions of existing video games, like Fallout and Sid Meier’s Civilization. Many are steeped in complicated fantasy worlds with Vikings and labyrinthine backstories, but others are simple logic contests. Still more are not competitive at all and only aim for players to work together in pursuit of a desirable conclusion. Yes, everyone can lose.

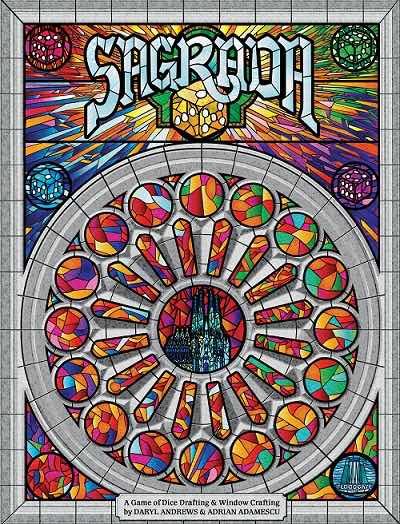

The internet has played a significant role in this revolution, creating a space for independent game makers to fund and sell their ideas. The independent tabletop game company Floodgate Games released their Spanish basilica-inspired dice game, Sagrada, this year after a Kickstarter campaign that raised over $150,000. The visually striking board game involves using colored dice to “construct a stained-glass masterpiece” with rules reminiscent of Sudoku.

Another Kickstarter success was the wildly popular — and risqué — Cards Against Humanity: A Party Game for Horrible People. Derivative of the family card-comparison game Apples to Apples, Cards Against Humanity ditched wholesome cultural and historical references for politically incorrect phrases like “demonic possession” or “a homoerotic volleyball montage,” or “actually taking candy from a baby.” The ribald and racy game earned an estimated $12 million in its first two years of production despite being free for download online (1.5 million downloads took place as well). The small Chicago group in charge of the debauchery continues to churn out expansion card decks, and they refuse to sell the brand.

Small-time board game publishers have seen enormous success given a platform to market and sell their games. This wasn’t always viable, though, with tabletop gaming. At the advent of commercial board gaming in the U.S., the late-1800s, Parker Brothers was the big name in board game development and manufacturing. Early games like Banking and Mansion of Happiness rewarded capitalistic pursuits and moral values.

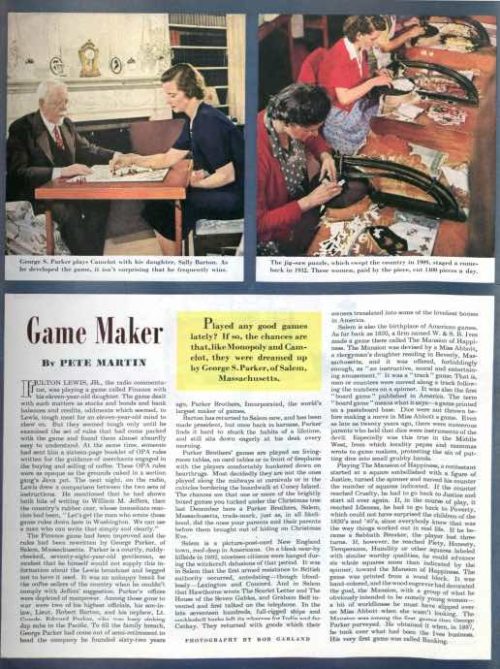

In a Post story from 1966, “Pass Go and Retire,” Parker Brothers executives divulge their strategy of crowd-sourcing to find another Monopoly-tier hit: people from around the country would send their ideas with hopes that it would strike a fancy with the gatekeepers of fun.

“The inventors of successful board games are invariably amateurs, and not one has ever struck it rich more than once,” Parker Brothers disclosed. No one person was ever certain of what would become a hit, and the company relied on numerous test groups of various demographics. There were some gaming no-nos though, like witches and — early on — dice.

Pete Martin’s 1945 profile on Parker Brothers, which was located in Salem, Massachusetts, tells that “The game of Witchcraft was dropped when the embarrassed descendants of those New Englanders who took part in the seventeenth-century witch hunt asked that it be discontinued,” and, “Even as late as twenty years ago there were numerous parents who held that dice were instruments of the devil.” It is safe to say that Dungeons & Dragons would have been rejected vehemently.

Many newer board games laugh in the face of Parker Brothers’ old unwritten rules of what makes one popular: “A successful game should be simple, shouldn’t take too long to play, and even children should find it easy to learn.” In defiance of this advice, a 2016 cooperative game called Gloomhaven features a 52-page encyclopedia of a rule book whose contents are as foreign as a specialized medical textbook to those not in the know: “Monster statistic cards give easy access to the base statistics of a given monster type for both its normal and elite variants. A monster’s base statistics will vary depending on the scenario level.”

Still, for want of less time in front of screens or for lack of cash for extravagant entertainment, people keep playing games. Maybe it isn’t a consequence of anything other than the unbridled joy that they bring. One gamer wrote to Parker Brothers around 1966, “My cousin got married and went to Germany for her honeymoon, and she said they played Monopoly every night for enjoyment.” For some, the pastime has always been more than a necessity on a rainy day.

Check out the hidden history of Monopoly in the Post’s recent article, “Who Really Invented Monopoly?”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now