The following item appeared in The Saturday Evening Post on December 27, 1828, shortly after Noah Webster published his American Dictionary of the English Language:

Webster’s Dictionary has been issued from the press of Mr. Converse, the publisher. It is contained in two large quarto volumes, and is executed in a manner highly creditable to the press of our country. He introduces into his new dictionary as legitimate, the word lengthy. We should like to know whether his reasons for doing so are breadthy and strengthy.

Acting as authorities on spelling, meaning, and usage, dictionaries have courted controversy from the beginning. That controversy thickened around the turn of the century as competition grew and copyright became an issue. Dictionary publishers’ disputes and dilemmas can be traced through their advertisements that appeared in the Post over time.

Click to Enlarge

If we had a copy of a Webster’s Dictionary from 1899, we would look up the word adequate to see if there is some older, more superlative definition of the word we don’t know about. It sounds wholly incongruous compared with the hyperbole-heavy advertisements of the 20th century to advertise a dictionary’s “sizable vocabulary, complete definitions and adequate etymologies.”

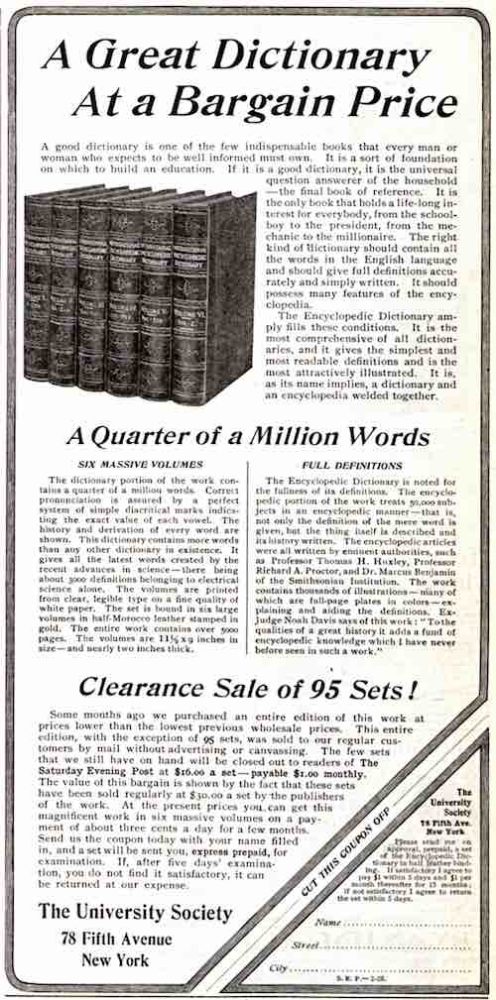

The University Society’s six-volume Encyclopedic Dictionary was likely more encyclopedia than dictionary, but it did, according to this ad, contain definitions for 250,000 words. This type of blurring of dictionaries as authorities on language and dictionaries as authorities on everything would continue, both in advertisements and in the minds of information-hungry consumers.

Click to Enlarge

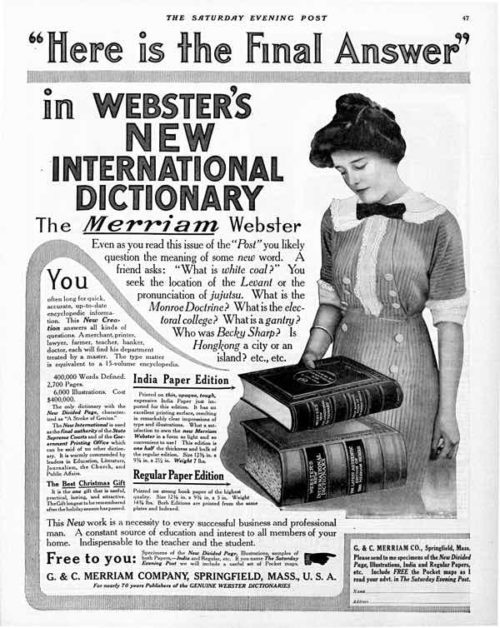

In 1909, the Merriam Company issued a completely revised edition of its unabridged dictionary, calling it Webster’s New International Dictionary of the English Language. Readers of the Post were further enticed to buy with the promise of exclusive free gifts — a marketing tactic that lives on today.

Click to Enlarge

At the turn of the century, George W. Ogilvie published what he called Webster’s Dictionary. Since the Merriam Company had bought all rights to Noah Webster’s creation after he died in 1843, a copyright infringement lawsuit naturally followed. In 1908, the First Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the copyright on the name had run out in 1889 and that “Webster” was in the public domain. That meant that anyone could publish a dictionary and call it Webster’s Dictionary. And many companies did.

Following the ruling, Merriam-Webster ads began including warnings like the one in this full-page 1910 ad: “Caution. Look for the circular trade-mark and our name — MERRIAM — on the title-page. Beware of so-called Webster dictionaries.”

Click to Enlarge

For many children, a dictionary ranks somewhere just ahead of new socks as an exciting Christmas gift. But Santa knows that the knowledge in a dictionary is a gift for the whole family that will be around long after those socks are too threadbare to darn. One can just imagine old Saint Nick attempting to stuff an unabridged dictionary into a Christmas stocking.

Click to Enlarge

Because it was less expensive and more accessible than a multivolume encyclopedia, the dictionary became, for many, the go-to source for information about all facets of life. The Merriam Company seized on this idea and began marketing its unabridged dictionary as “The Supreme Authority.”

Click to Enlarge

An unabridged dictionary is a large, heavy thing. But in the 1910s, the Merriam Company offered a new edition printed on thinner, lighter India paper. The image in this 1912 ad implies that, at only 7 pounds, the India paper edition is so light even a woman can lift it.

Click to Enlarge

Not all publishers attempted to exploit Webster’s name to garner sales. This 1913 ad shows Funk and Wagnalls’ simply named New Standard Dictionary, along with an endorsement from fiction author and Post contributor Jack London. Considering the trend at the time to exclude vulgarities and “substandard” terms — not to mention the sometimes impossible task of tracing word etymologies — it’s unlikely that this dictionary delivered on this ad’s promise to give “the source, spelling, and meaning of every living word in the English language.”

Click to Enlarge

The Merriam Company’s pursuit of its copyright neither began nor ended with the Court’s 1908 decision. In 1917, a suit against the Saalfield Publishing Company resulted in an injunction barring that company from using the title Webster’s Dictionary without including a disclaimer that it wasn’t the original Webster’s Dictionary. Even 20 years later, in ads for its second edition of the New International Dictionary, the Merriam Company was still letting the public know.

Click to Enlarge

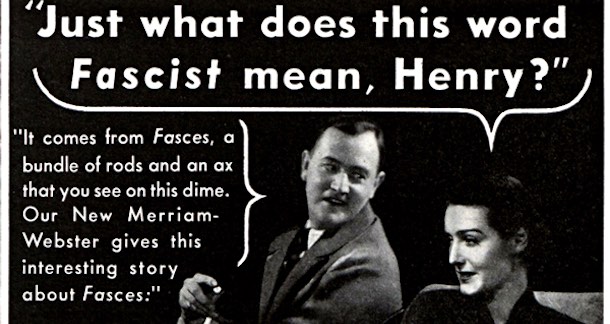

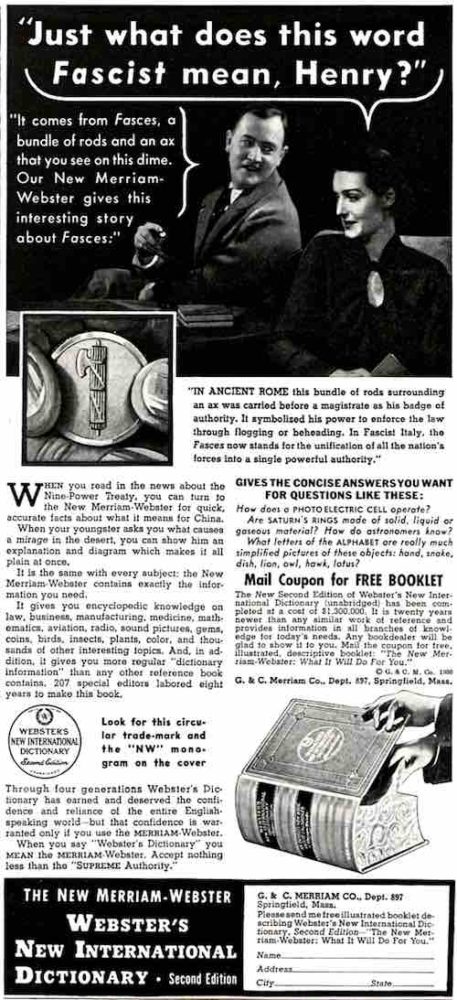

In 1938, trouble was brewing in Europe, and dictionary ads of the times offered clarity and understanding for Americans trying to comprehend what was going on “over there.” To this day, dictionaries can offer insight into complex world issues in ways Noah Webster probably never imagined.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now