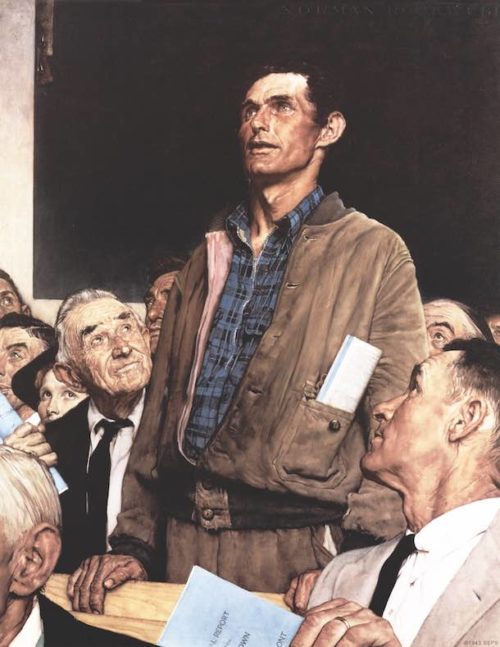

In 1943, the Post commissioned four writers to craft an essay to accompany each of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings, which had quickly come to represent America’s moral imperative during World War II. You can read the other three essays here.

Freedom of Speech

Originally published February 20, 1943

In a small chalet on the mountain road from Verona to Innsbruck, two furtive tourists sat, pretending not to study each other. Outdoors, the great hills rose in peace that summer evening in 1912; indoors, the two remaining patrons, both young, both dusty from the road, sat across the room from each other, each supping at his own small table.

One was a robustly active figure, dark, with a bull head; the other was thin and mouse-haired. It was somewhat surprising to see him take from his knapsack several sketches in watercolor. Upon this, the dark young traveler, who’d been scribbling notes in a memorandum book, decided to speak.

“You’re a painter, I see.”

“Yes,” the insignificant one replied, his small eyes singularly hard and cold. “You, sir, I take to be a writer?”

The dark young man brought his glass of red wine and his plate of cheese and hard sausage to the painter’s table. “You permit?” he asked as he sat down. “By profession I am a journalist.”

“An editor, I think,” the watercolor painter responded. “I might guess that you’ve written editorials not relished by the authorities.”

“Why do you guess that?”

“Because,” the painter said, “when other guests were here, a shabby man slipped in and whispered to you. A small thing, but I observed it, though I am not a detective.”

“Not a detective,” the dark young man repeated.

“And yet perhaps dangerously observant. This suggests that possibly you do a little in a conspiratorial way yourself.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Because of your appearance. You’re precisely a person nobody would notice, but you have an uneasy yet coldly purposeful eye. And because behind us it’s only a step over the mountain path to Switzerland, where political refugees are safe.”

“Yes, no doubt fortunately for you!” The mouse-haired painter smiled. “As for me, I am in no trouble with the authorities, but I admit that I have certain ideas.”

“I was sure you have.” The journalist drank half his wine. “Ideas? With such men as you and me, that means ambitions. Socialism, of course. That would be a first step only toward what we really want. Am I right?”

“Here in this lonely place” — the painter smiled faintly — “it is safe to admit that one has dazzling thoughts. You and I, strangers and met by chance, perceive that each in his own country seeks an extreme amount of success. That means power. That is what we really want. We are two queer men. Should we both perhaps be rightly thought insane?”

“Greatness is easily mistaken for insanity,” the swarthy young man said. “Greatness is the ability to reduce the most intricate facts to simple terms. For instance, take fighting. Success is obtained by putting your enemy off his guard, then striking him where he is weakest — in the back, if possible. War is as simple as that.”

“Yes, and so is politics,” the painter assented absently as he ate some of the fruit that formed his supper. “Our mutual understanding of greatness helps to show that we are not lunatics, but only a simple matter of geography is needed to prove our sanity.”

“Geography?” The journalist didn’t follow this thought. “How so?”

“Imagine a map.” The painter ate a grape. “Put yourself in England, for instance, and put me and my dazzling ideas into that polyglot zoo, the United States of America. You in England can bellow attacks on the government till you wear out your larynx, and some people will agree with you and some won’t, and that is all that would happen. In America I could do the same. Do you not agree?”

“Certainly,” the journalist said. “In those countries the people create their own governments. They make them what they please, and so the people really are the governments. They let anybody stand up and say what he thinks. If they believe he’s said something sensible, they vote to do what he suggests. If they think he is foolish, they vote no. Those countries are poor fields for such as you and me, because why conspire in a wine cellar to change laws that permit themselves to be changed openly?”

“Exactly.” The watercolor painter smiled his faint strange smile. “Speech is the expression of thought and will. Therefore, freedom of speech means freedom of the people. If you prevent them from expressing their will in speech, you have them enchained, an absolute monarchy. Of course, nowadays he who chains the people is called a dictator.”

“My friend!” the dark young man exclaimed.

“We understand each other. But where men cannot speak out, they will whisper. You and I will have to talk out of the sides of our mouths until we have established the revolutions we contemplate. For a moment, suppose us successful. We are dictators, let us say. Then in our turn do we permit no freedom of speech? If we don’t, men will talk out of the sides of their mouths against us. So they may overthrow us in turn. You see the problem?”

“Yes, my friend. Like everything else, it is simple. In America or England, so long as governments actually exist by means of freedom of speech, you and I could not even get started; and when we shall have become masters of our own countries, we shall not be able to last a day unless we destroy freedom of speech. The answer is this: We do destroy it.”

“But how?”

“By means of a purge.”

“Purge?” The word seemed new to the journalist. “What is that?”

Once more was seen the watercolor painter’s peculiarly icy smile. “My friend, if I had a brother who talked against me, either out of the side of his mouth or the front of it, and lived to run away, he might have to leave his wife and child behind him. A purge is a form of carbolic acid that would include the wife and child.”

“I see.” The dark youth looked admiring, but shivered slightly. “On the one hand, then, there is freedom of speech, and on the other this fatal acid you call a purge. The two cannot exist together in the same country. The people of the earth can take their choice, but you and I can succeed only where we persuade them to choose the purge. They would be brainless to make such a choice — utterly brainless!”

“On the other hand,” said the painter, “many people can be talked into anything, even if it is terrible for themselves. I shall flatter all the millions of my own people into accepting me and the purge instead of freedom.”

He spoke with a confidence so monstrous in one of his commonplace and ungifted appearance that the other stared aghast. At this moment, however, a shrill whistle was heard outside. Without another word the dark young man rose, woke the landlord, paid his score and departed hurriedly.

The painter spoke to the landlord: “That fellow seems to be some sort of shady character, rather a weak one. Do you know him?”

“Yes and no,” the landlord replied. “He’s in and out, mainly after dark. One meets all sorts of people in the Brenner Pass. You might run across him here again, yourself, someday. I don’t know his whole name, but I have heard him called ‘Benito,’ my dear young Herr Hitler.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now