This article and other features about the golden era of American cars can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, American Cars: 1940s, ’50s & ’60s.

This article and other features about the golden era of American cars can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, American Cars: 1940s, ’50s & ’60s.

It took vision (and money) to replace the network of narrow, unsafe roadways originally designed for horse-and-buggy travel with the wide, safe concrete thoroughfares we take for granted today.

Stevan Dohanos

October 9, 1954

(© SEPS)

—Originally published January 6, 1940—

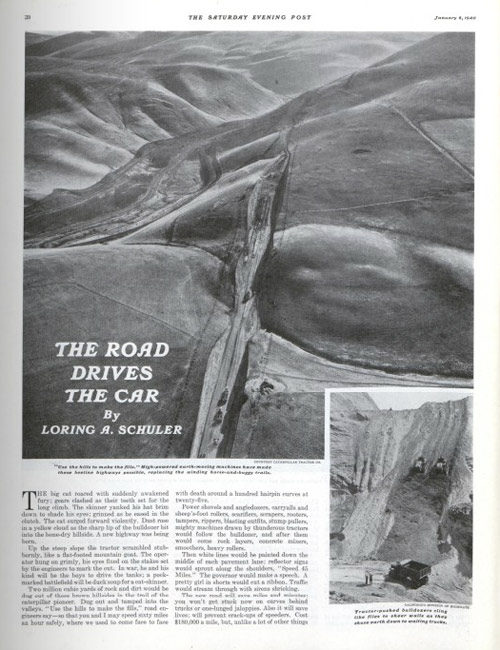

The big cat roared with suddenly awakened fury; gears clashed as their teeth set for the long climb. The skinner yanked his hat brim down to shade his eyes; grinned as he eased in the clutch. The cat surged forward violently. Dust rose in a yellow cloud as the sharp lip of the bulldozer bit into the bone-dry hillside. A new highway was being born.

Up the steep slope the tractor scrambled stubbornly, like a flat-footed mountain goat. The operator hung on grimly, his eyes fixed on the stakes set by the engineers to mark the cut. In war, he and his kind will be the boys to drive the tanks; a pockmarked battlefield will be duck soup for a cat-skinner.

Two million cubic yards of rock and dirt would be dug out of those brown hillsides in the trail of the caterpillar pioneer. Dug out and tamped into the valleys. “Use the hills to make the fills,” road engineers say — so that you and I may speed 60 miles an hour safely, where we used to come face to face with death around a hundred hairpin curves at 25.

Power shovels and angle-dozers, carryalls and sheep’s-foot rollers, scarifiers, scrapers, rooters, tampers, rippers, blasting outfits, stump pullers, mighty machines drawn by thunderous tractors would follow the bulldozer, and after them would come rock layers, concrete mixers, smoothers, heavy rollers.

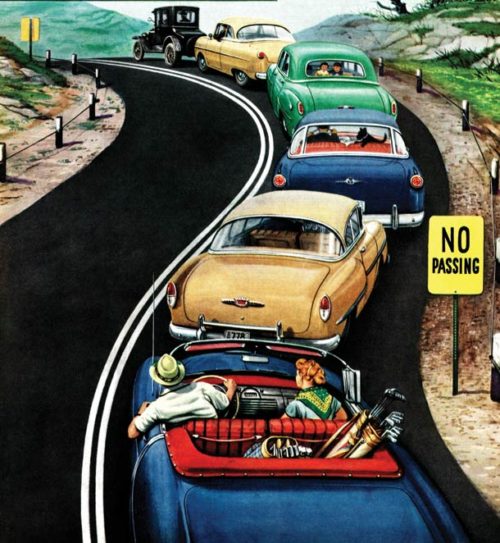

Then white lines would be painted down the middle of each pavement lane; reflector signs would sprout along the shoulders, “Speed 45 Miles.” The governor would make a speech. A pretty girl in shorts would cut a ribbon. Traffic would stream through with sirens shrieking.

The new road will save miles and minutes; you won’t get stuck now on curves behind trucks or one-lunged jalopies. Also it will save lives, will prevent crack-ups of speeders. Cost $180,000 a mile, but, unlike a lot of other things in government, it’s paid for, and before it was built, engineers had figured how much revenue it would bring in to build more of the same kind. That’s where your gasoline tax goes.

The gas tax is beginning to buy more than asphalt and concrete. On newer roads it is a form of accident and life insurance, which doesn’t pay for death but pays you dividends in life and limb. “Our job,” road builders say, “is to provide a transportation system that the reasonably careful driver can use at 60 miles or more an hour in safety and in comfort and without surprise.”

And so they’re building automatic highways, which swing you safely round curves without slackening speed, give you ample room to pass trucks without danger of sideswiping, warn you by prepared condition of the pavement to get back on your side of the road, steer you through an intersection maze with neither words nor music from the traffic cops.

Out on the Mojave Desert, where summer heat is so intense that motorists travel at night and travel fast, cars constantly ran off a certain curve and wrecked themselves. The road was wide enough; the pavement was good; sight distance was without obstruction. Yet drivers couldn’t stick to the highway round that bend.

California’s safety engineer, J.W. Vickrey, studied, pondered, measured, found that the superelevation had been built to hold cars on that curve at 45. He had it rebuilt, banked for 75-mile speed. The accidents stopped.

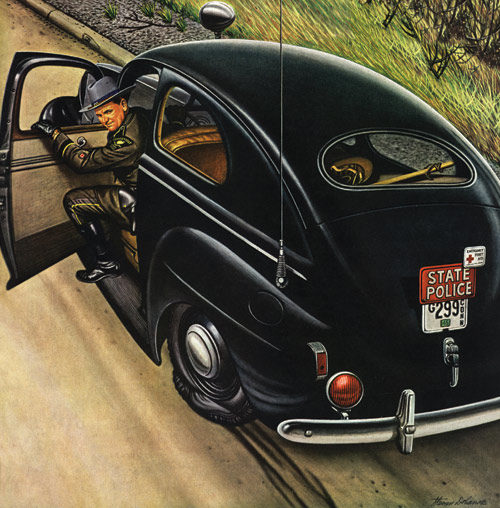

“Not very cooperative with the highway patrol,” someone commented.

“We’re trying to save lives,” Vickrey retorted. “If the police think they can stop speeding out there by arrests, they’re welcome to try. We are realists.”

Stevan Dohanos

March 24, 1945

(© SEPS)

Safety without Slogans

Briefly, that tells the story of the newest highway-safety campaign. It is very young. It has no slogans. It is seeking no publicity — no billboards, no write-ups in the papers, no horror pictures of death and disaster. It doesn’t even ask the motorist to slow down. But already its mechanical tricks are beginning to show results. It will get more as we create:

Freeways, which will limit city-gateway highways to through traffic, released from present hindrances and hazards caused by side roads, driveways, parking, hot-dog stands, and 25-mile zoning.

Separate roads for trucks — sometime in the future because of the high cost, but sure to come to relieve delays and accidents.

More four-lane divided highways, especially for 10 miles each side of cities, where congestion piles up, and on hills where you can’t see what’s coming.

More three-lane roads, with roughened center strips.

Longer sight distances for safe passing.

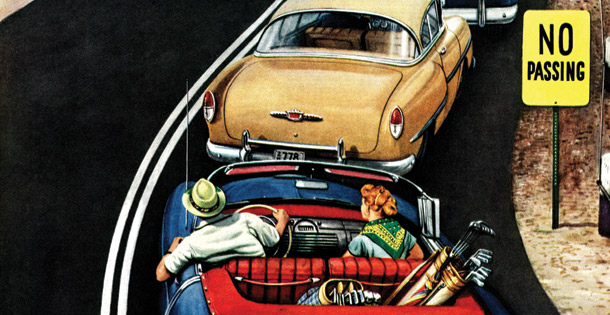

Shorter curves if passing must be prohibited — a very new idea in safety construction, growing out of the fact that drivers lose patience and take a chance if no-passing zones are more than a mile in length.

Intersections scientifically channelized by islands or pavement markings for the benefit of timid drivers.

Greater super-elevation of curves on high-speed highways.

Sandpaper finishes to prevent skidding.

Better stability of foundations.

Postponement of deterioration by intensive research.

Cement-concrete mixtures that will not buckle.

Rubber joints in concrete highways.

Eleven-foot traffic lanes for safe maneuvering at high speed.

Traffic stripes that are nationally understandable.

Smoother pavement as determined by the bump-meter — old macadam often had 70 inches of bumps per mile; new concrete has been laid with as little as 3 ½ inches of irregularities per mile.

Use of fixed-time light signals as defined by traffic count and not by pride or salesmanship — 1,000 vehicles an hour is the minimum to justify the red and green lights.

Stronger bridges — quickly, if we should go to war.

More parking lots in cities — more necessary, engineers declare, than overhead highways, and a lot less expensive.

Pedestrian areas in cities, where motor traffic will be forbidden.

Some of these improvements are already in effect. All of them are being studied nationally, in highway laboratories, on the roads themselves. Engineered safety is based not on guesswork, but on mathematics; not on emotion, but on science, research, electric eyes, and careful recordkeeping. A new idea in construction or design, discovered in California or Missouri or New York, quickly becomes all-American through the coordinating efforts of the Association of State Highway Officials and the National Conference on Street and Highway Safety. Federal aid eliminates state boundaries on the through routes. In effect, all our transcontinental highways, east and west and north and south, are military roads, though we don’t call them that. They have been studied with the War Department, and lately highway engineers have been working with the motor manufacturers to the end that chassis for big guns shall have their weight distributed on many wheels. Most bridges were not built for quite such heavy loads.

All down the line, highway builders are busily planning for growth. Charles Purcell, California’s chief highway engineer, and others like him have not only an unquenchable desire to build more and better and safer roads but also a burning passion to get the gas-tax money’s worth.

In his 11 years in office, Purcell has supervised the spending of a quarter of a billion dollars, but he and his men still think in terms of what can be. “The ultimate development of our transportation system will cost again as much as already has been spent,” Purcell says, “but just as they stand today, our national highways are the finest demonstration of working democracy that the world has ever seen.”

—“The Road Drives the Car,” January 6, 1940

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now