An authentic, 30-foot, mid-19th century Haida totem pole once stood in a very unlikely spot – the Indianapolis neighborhood of Golden Hill. How did a totem pole from the Pacific Northwest end up in Indiana? The story involves a World’s Fair, a push for Alaska’s statehood, and a reluctant Indianapolis businessman.

The 1904 World’s Fair was underway in St. Louis. Alaska governor John Brady had collected fifteen totem poles in 1903 to display at the fair from the remote coastal island native villages of southeast Alaska. Brady was a far-sighted man motivated by a sincere respect and concern for Alaska’s Native American peoples. He collected these and other artifacts in an attempt to preserve their traditional arts. Trusted by the village leaders whom he knew well through his activities as a continual advocate as a church missionary, and as governor, Brady was successful in obtaining these objects because of the immense esteem in which Native Alaskan held him.

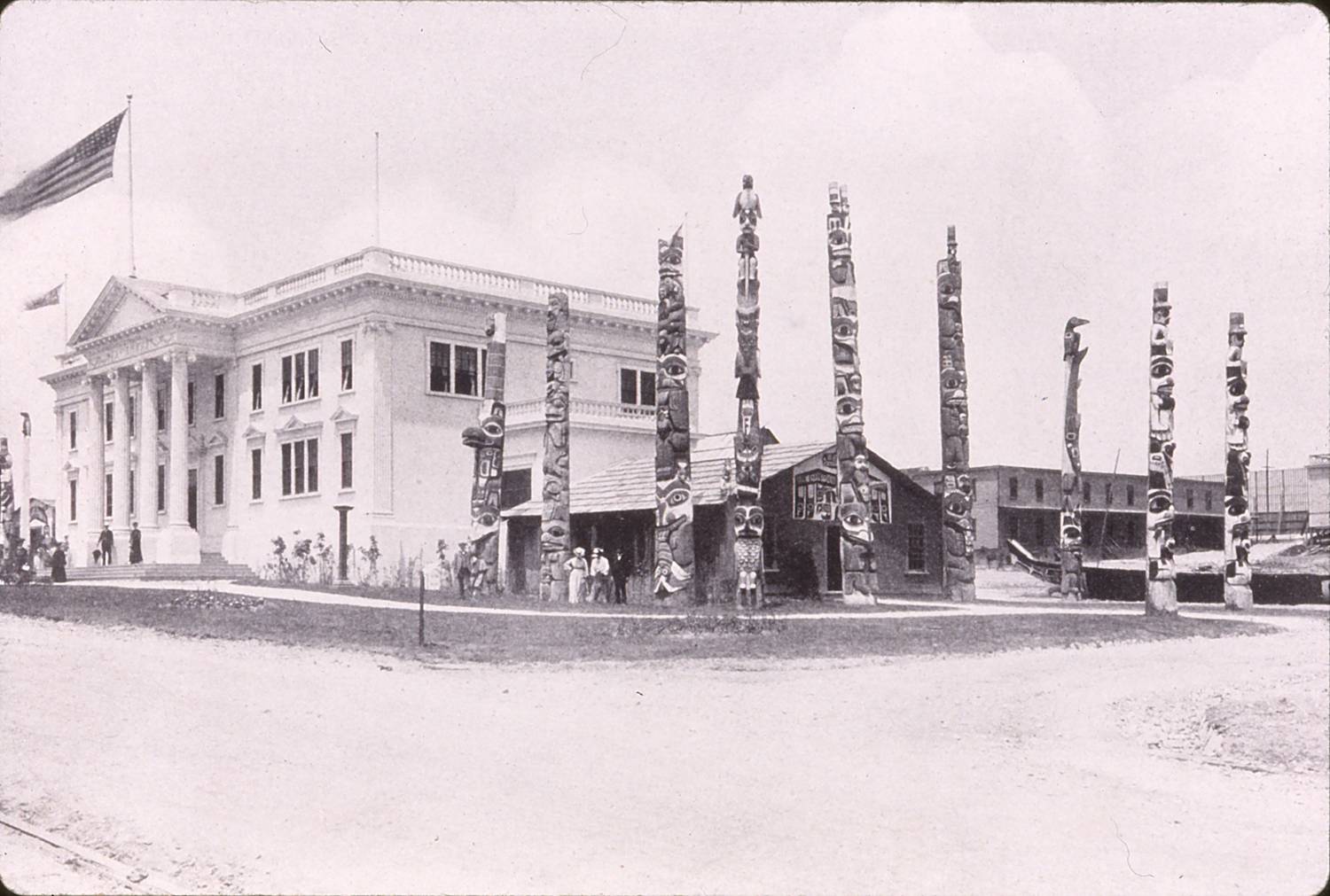

Brady was also motivated by his desire for statehood. Qualification for Alaska to become a state would require significant development and immigration. He was determined to make the Alaska Pavilion at the World’s Fair stand out from the dozens of other fairground spectacles, and he felt the dramatic wood sculptures would accomplish this goal. Fourteen of the fifteen poles he had collected and brought to the St. Louis Fair were installed around the Greek revival-styled exhibit building flanked on both sides by authentic native houses. The totem poles indeed created an unusual and distinctive appearance, attracting many visitors.

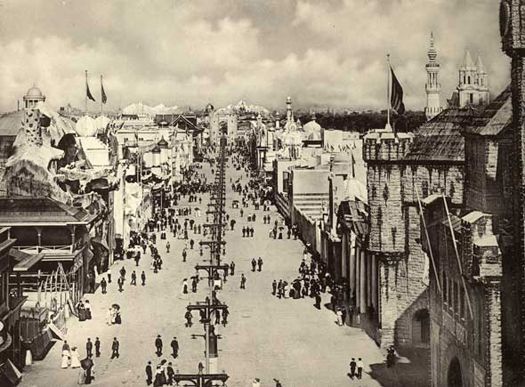

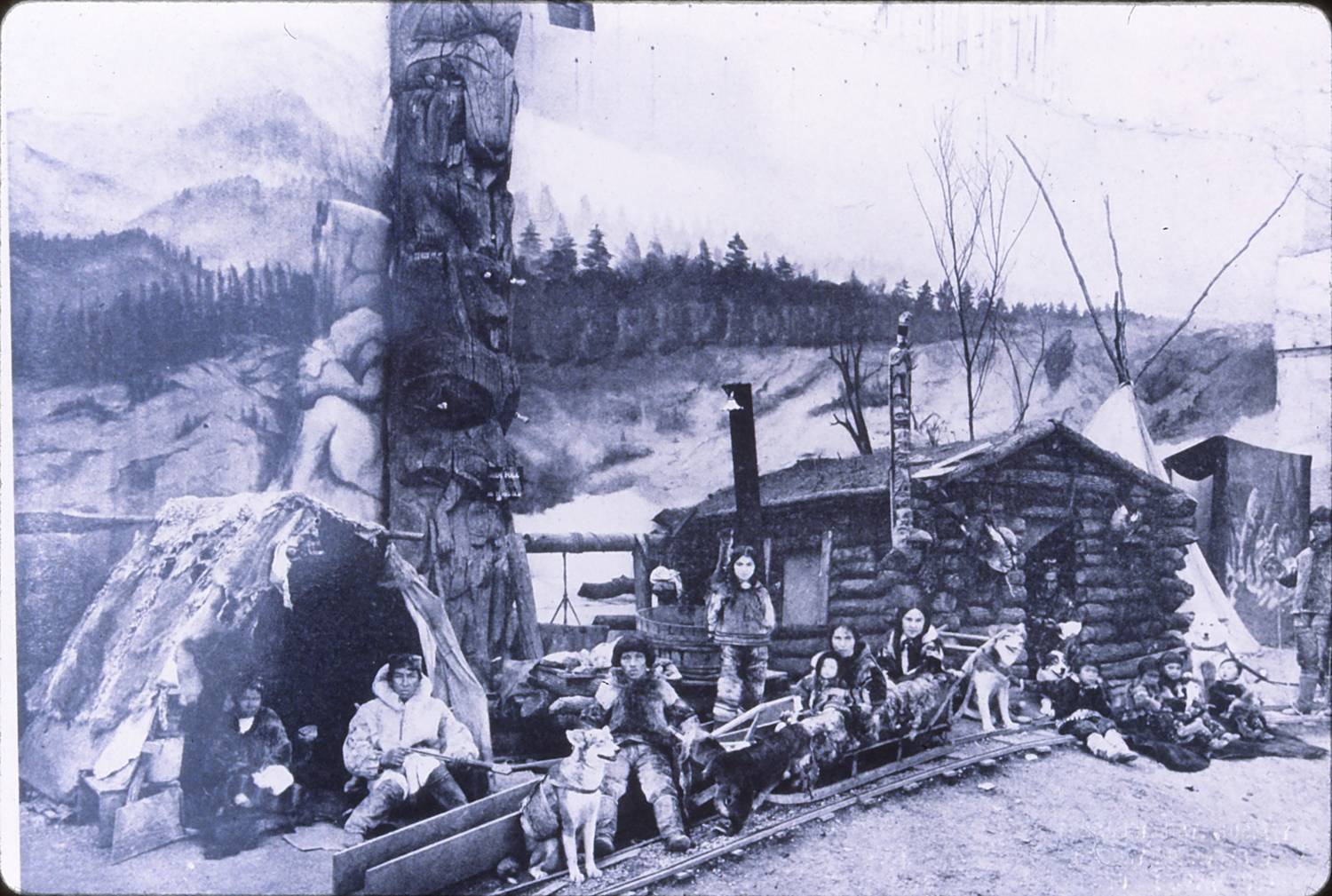

The fifteenth totem pole brought by Brady was loaned to the Esquimaux Village during the fair. The Esquimaux Village was one of the exhibits along what was known as the Pike, one of the most popular features of the fair. It was a street more than a mile in length lined with private concessions of many elaborate and unusual attractions requiring separate admission fees. The Esquimaux Village exhibit was an enormous building with an iceberg-like facade. Inside the exhibit were a miniature lake and various scenes of Eskimo life.

The lone totem pole stood at the Esquimaux Village exhibit in the Klondike mining camp setting. (It seems that no one was bothered by the blending of Eskimo and Northwest Coast Indian cultures.) The pole had actually originated in the native village of Koianglas on a small island just off of Prince of Wales Island and was donated to Brady by “Yealtatsee” (the family now spells his name Yeltatzie), a very prominent Haida clan chief. The pole had been carved in the mid-19th century in southeast Alaska by the Kaigani (Alaskan) Haida, and was a Wasgo type, which meant it told the mythological sea monster story.

When the fair concluded, all but two of the fifteen totem poles collected by Governor Brady were returned to Alaska, as he had promised the Native American donors. These thirteen poles now stand in Sitka National Historical Park in southeast Alaska and comprise the well-known and -studied Brady collection of totem poles.

But apparently, possibly because Alaska could not afford to ship all the poles back and because some of the poles were in relatively poor condition, Brady decided to sell two of the totem poles. Brady sold one of the poles that stood outside the Alaska Pavilion to the Milwaukee Public Museum for $500. The fate of the 15th pole — the lone pole that had stood in the Esquimaux Village — remained a mystery to historians in Alaska and Canada for over 90 years.

Only recently was it uncovered through my research that Brady sold this totem pole to the Banner Buggy Company in St. Louis. The buggy company’s president, Russell E. Gardner, was a close friend of Indianapolis businessman David M. Parry. Mr. Gardner acted in association with several other St. Louis businessmen and possibly the Governor of Missouri to make a gift of the pole to Parry – a gift he did not want. But because Parry’s son Maxwell became fascinated with the pole, it was erected on the Parry property in 1905. In 1914-1915, about the time of Parry’s death, the Parry family subdivided the estate into the neighborhood of Golden Hill. The Indianapolis newspapers advertised Golden Hill lots for sale in a park-like setting “under the great totem.”

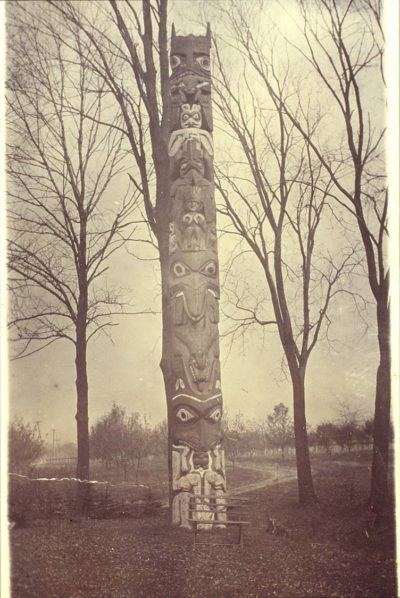

The pole stood at the south end of the neighborhood on a small grassy triangle between the roads. In May 1914, Max Parry wrote a prophecy and placed it in a bottle on top of the totem pole. The prophecy gives one some idea as to the poor condition of the pole only ten years after it was placed in Golden Hill. Max writes, “Having completed the job of scattering various colors about these nifty little figures, as well as having plugged up the holes that have begun to appear…I prophesy that within five years the pole will be in such a state of rottenness that it will scarcely stand.” Max’s prediction concerning the pole was quite wrong. The pole, which by that time was more than 50 years old, would stand in Golden Hill for another 25 years.

The 30-foot totem pole became a landmark where local children met to play and where young couples would pause to ponder their futures. There was great speculation about the pole’s history and discussion regarding the symbolic meaning of its carved figures. The pole was not only an important part of the neighborhood identity but also a curious object that Indianapolis motorists would come to admire on a Sunday afternoon drive.

During the 1920s, the pole began to seriously deteriorate and became a matter of concern to the Parry family and the neighborhood. In 1929, the Parry family began discussions with the Indianapolis Children’s Museum regarding its donation for restoration and display on the museum’s front lawn. However, for reasons that are unclear, the pole continued to stand in Golden Hill until the spring of 1939, when, rotten from exposure to the elements and termites, it fell face down in a storm. Neighborhood children took a few small pieces of the pole home as souvenirs. Still with hopes of restoration and display, what remained of the pole was hauled away by the Children’s Museum with the help of Indiana Bell Telephone Company. What happened to the pole after its arrival at the museum remains a mystery, but evidently the totem pole was never displayed and was eventually discarded. No part of the totem pole is known to exist today.

Because of the historical significance of the Golden Hill Totem Pole, I created the Eiteljorg Museum Totem Pole Project in 1991 in an effort to have this totem pole re-created and raised again in Indianapolis.

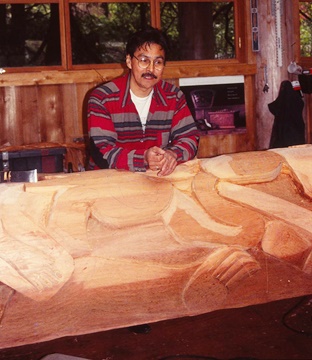

The first element of the project was the commission of an Alaskan Haida artist to re-create the totem pole. A fifth generation carver, Lee Wallace of Ketchikan, was selected. It turns out, quite serendipitously, that Wallace’s great-grandfather Dwight Wallace (1822-1913) carved the original Golden Hill totem pole.

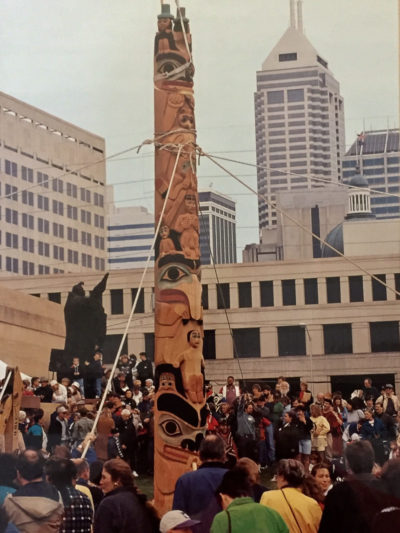

Fundraising for the project was completed in May 1993, with local support coming from individuals, school children, corporations, and foundations. In April 1996, the completed totem pole was raised on the grounds of the Eiteljorg Museum for the people of Indiana to appreciate, view, and study. The museum held a grand traditional pole raising with feasting and associated scholarly and educational programming. Indiana Native Americans and representatives of the southeast Alaskan native community including the carver and his family, dancers and Haida and Tlingit tribal elders, and members of the Yeltatzie and Parry families were involved in the celebration. The original totem pole site in Golden Hill was commemorated with the placement of a modest monument and an Indiana State Historical Marker along Totem Lane.

The raising of the new totem pole at the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis completes a story that began in Alaska more than 150 years ago. The pole raising was a grand historic day, 91 years after the original pole arrived in Indianapolis, when the Parry, Yeltatzie, and Wallace families all met and united as one American family.

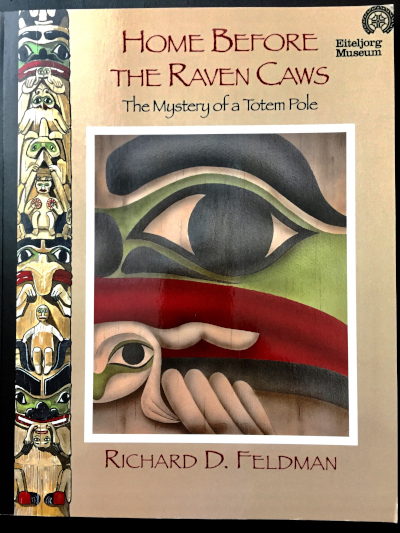

© 2015 Richard D. Feldman. Dr. Feldman’s book about his research into the Golden Hill totem pole and his efforts to recreate it can be purchased through the publisher, The Indiana Historical Society Press or through Amazon Books. Be sure to get the second edition. Appropriate for both young adults and adult readers.

© 2015 Richard D. Feldman. Dr. Feldman’s book about his research into the Golden Hill totem pole and his efforts to recreate it can be purchased through the publisher, The Indiana Historical Society Press or through Amazon Books. Be sure to get the second edition. Appropriate for both young adults and adult readers.

All images courtesy of Richard D. Feldman

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now