In the annals of Wiffle Ball, that breezy June afternoon in 1966 will forever remain etched in gravel.

My brother Martin stood on the pitcher’s mound, a dimly defined region between first base (the end of a downspout at the rear corner of our house) and third base (a piece of wood). It was just the two of us.

“Up at bat is Bill Newcott,” he said, narrating the game from the playing field. “He looks like he’d really like to put one out of here today. Here comes the pitch …”

A hollow thud echoed through the neighborhood, the sound of a plastic ball catching the sweet spot of a plastic bat, not that inconsequential “click” you heard most of the time. No, this was a good, throaty, slugger’s “whoomp.”

“Holy cow!” Martin exclaimed in homage to New York Yankee announcer Phil Rizzuto.

In a graceful arc, the ball headed up toward the canopy of trees that overhung the field in those days. But instead of becoming tangled in the branches, the sphere found its way through a gap in the trees and continued its trajectory up… up…

“Holy cow!” Martin exclaimed again, pointing down the driveway as the ball slapped up against the wall of the apartment house all the way across the street!

A hollow thud echoed through the neighborhood; the sound of a plastic ball catching the sweet spot of a plastic bat.

We did our best to measure the distance of that moonshot, putting one foot in front of the other and counting off our steps. Initial estimates placed it at 300 feet. Subsequent measurements trimmed the actual distance to 110.

There is a certain melancholy attached to an athlete who peaks so young (in this case, age 11). Looking back now, the ensuing 50 years or so have offered their share of successes, but few moments have made my heart stand still the way it did as I stood there in a scratched-out batter’s box, having a Mickey Mantle moment.

Our Cathedral of Wiffle Ball on Sunnyside Avenue in Dumont, New Jersey, was in reality an unpaved driveway, 12 feet across at its widest spot, nestled between a small tree-studded lot (“the woods”) and our house. The garage at one end of the playing field served excellently as a backstop, except when the ball was fouled back over the garage and into our neighbor’s backyard. This was patrolled by a large, unfriendly dog, but we had rules for that: If the dog ate the ball, the batter was out. If the dog merely mangled the ball, the batter’s team lost an out the following inning.

Sunnyside Avenue Wiffle Ball followed this tradition of clear, concise rule-making throughout its golden era, which lasted from 1963 to somewhere around 1973. In that decade, legends were born. Dynasties rose and fell. Windows were broken (not so much in the early days, but later, as adolescence set in, even with a plastic ball one mighty swing could do real damage to a pane of glass just 20 feet away).

The distance from home plate to the first base downspout was 15 feet. If a car was parked in the driveway, the front license plate was second base; otherwise a rock, a piece of wood, or a scratched-out box would do. Third base was the end of a board my father had half-buried along the edge of the driveway in a futile attempt to block the garbage and dead leaves that blew over from “the woods.”

Anything that landed in the street was a home run. Anything that landed in the driveway was fair, and anything that landed off of it was not. This unique ground rule led to us becoming expert in driving balls to straightaway center field, but it caused me some consternation when I endured an abbreviated career playing for my town’s Babe Ruth League.

“Newcott, you hit every ball up the middle,” my coach barked. “Can’t you pull it once in awhile?”

“No, coach, I can’t,” I admitted, heading back to the bench where I spent most of my time.

It should be noted that the Sunnyside Avenue Wiffle Ball league did not often use official Wiffle Balls — the variety with the holes in one end that supposedly give anyone the ability to throw a curve ball that will write your name in midair. Hitting was the name of our game, and the Wiffle Curve Ball just didn’t travel far enough. As sluggers, we preferred cheap hollow plastic balls, the kind that came four to a bag.

Also, the drawback of using actual Wiffle Balls became evident one autumn day when I popped one up and it became impaled on an overhanging branch. We had no rule for that, so we suspended play and started a new game with a new ball.

On a winter’s day a few months later, when he must have had nothing else to do, Martin threw rocks at the thing until it came down and he caught it. I was inside watching TV when he dashed in from the yard, holding the ball aloft. “Out!” he yelled. By mutual agreement, that ended the game.

While Martin and I were the primary figures in the Sunnyside Avenue Wiffle Ball league and most often played one-on-one, there were a number of journeyman players who drifted in and out of the lineup. We had to admit that when the three Richards brothers from across the street participated, it almost looked like we were playing an actual game and not simply two kids engaging in some sort of baseball-inspired Kabuki.

The ultimate proof of strength and championship ability was home run production. The author was the all-time home run king of the league, although in his fading years he was overtaken and ultimately surpassed by his younger brother (to whom he taught everything he knows). In 1966, at age 11, the author hit 52 home runs, including the aforementioned Longest One on Record.

Undoubtedly the most important regulation in the league was the now-famous “interference” rule. If a ball was headed fair but was then knocked foul by a branch, the batter could yell “interference” and it would be a dead ball and he got a do-over. If the ball was headed foul and then knocked fair, the fielder had the option of yelling “interference” or attempting to catch the ball. However, he had to yell “interference” before the ball hit the ground. Many a tussle and broken plastic bat resulted from arguments on this point. In the name of sportsmanship, the rule was eventually ditched.

A few other rules we relied on:

- “Invisible Men” often served as runners, since there were rarely enough players to occupy the bases. (If a fielder touched second before the hitter reached first base, the Invisible Man from first was out.)

- If a foul ball landed in the swimming pool (installed 1969), the batter was out.

- If the pitcher threw the ball through one of the broken windows of the garage, it was a wild pitch and the runners advanced.

The years passed, and in time, our bodies became unfit for driveway Wiffle Ball. First base was suddenly a mere two strides away from the plate. Also, the miniature plastic bat looked small and silly in our hands. I moved to California in 1977, and my parents moved to Buffalo the following year. In 1993, we had a family reunion and played Wiffle Ball in a field near my house; all five Newcott kids, our spouses, and even my 85-year-old dad. It was fun, but more than once Martin and I caught each other’s gaze and smiled wistfully. It wasn’t the same.

Occasionally I drive through my old neighborhood. I get out of the car and stand at the end of the driveway, recalling the glory days when kids could be heroes. And I find myself singing to myself that old Frank Sinatra song, “there used to be a ballpark, right here.”

Bill Newcott is the movie critic for The Saturday Evening Post.

This article is featured in the March/April 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

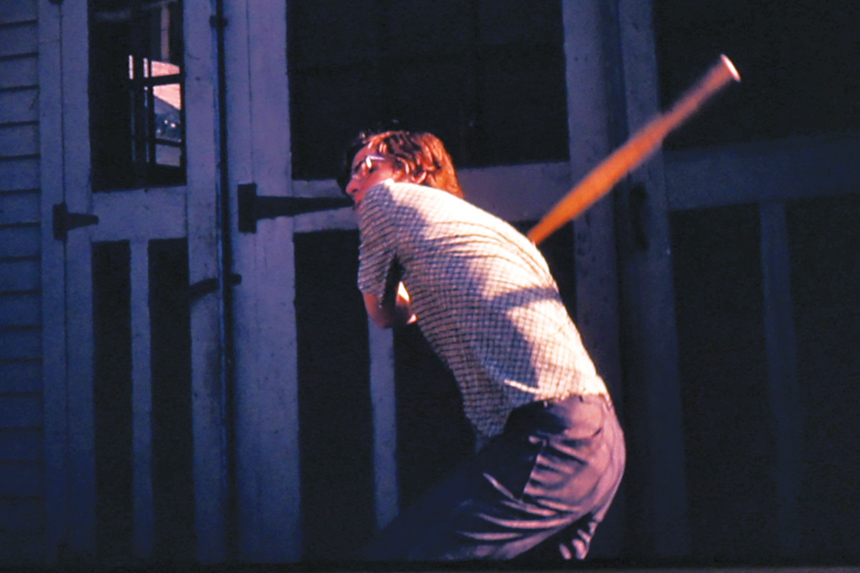

Featured image: Swinging for the fences: Author Bill Newcott showed he had not lost his form during his family’s 1974 Old Timer’s Day festivities. After years of shattered glass, the garage window panes had long since been boarded over. (courtesy Bill Newcott)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now