American writer Mildred Cram was nominated for an Oscar for her part in writing the film Love Affair in 1939, and her 1920 story “Stranger Things” was a finalist for the O. Henry Award. Cram’s short story “Birthday,” published in 1928, captures a widow’s struggle to live it up on her fiftieth birthday.

Published on September 15, 1928

Bessie had never enjoyed her birthdays, but after Henry’s death she tried not to notice them. “Good Lord! It’s the twenty-third!” Mrs. Struthers, on the eleventh floor, reached sideways and snatched the telephone from the bed table. “Bessie? It’s the twenty-third — you’re fifty! Many happy returns.”

Bessie, on the ninth, tried to grin into the mouthpiece. “Sweet of you, dear, to call me.” Henry, at least, had made of this day a ceremony. He had never forgotten to send her flowers or a box of candy, and, toward the end, rubies. “Sweet of you to call me.”

“How does it feel to be fifty?”

Well, how did it feel to be fifty? Bessie Lovering lay for a long time in bed, trying to detect any differences in herself. She felt exactly as she had felt yesterday or a year ago — in fact, she was practically certain that no change had taken place in her for thirty years. At twenty she had crossed a line. She had married Henry Lovering. “I, Henry, take thee, Elizabeth.” The veil. The blossoms. The importance of being Mrs. Lovering. She was still Mrs. Lovering. Being a widow only made marriage more important.

She lifted the phone again. “Service? Please send breakfast to 969.”

“Yes, madame. The usual?”

“Have you any corn muffins?”

“Yes, madame… Very good, madame.”

“Plenty of cream for the coffee, George. Yesterday I had to send for more.”

“Certainly, madame. Anything else?”

“That’s all.”

She stretched herself, throwing back the soft coverlet, to disclose her body clad in crêpe de chine, with insets of real lace and knots of baby-blue ribbon. She had pretty feet and she had always taken care of them. She wiggled her toes and lifted one leg.

“I must exercise.”

One leg up! The other leg up! Deep breath! Relax! She sank again into the deep mattress. Funny how sleepy she was, how tired, when she never did anything to tire herself. She had not been tired in the days of Henry’s poverty, when she rose at six o’clock to get breakfast for him and the boys. She closed her eyes and recalled the alarm clock crashing into her dreams, shattering them, and the cold dark room, and Henry, in his bare feet, sitting on the edge of the bed, groaning “Gosh, mother, I hate to get up!” until she shook him awake.

Was Henry still objecting to getting up, wherever he was? Where was Henry? She must ask the swami. He seemed to have that faculty, apparently granted only to dark Hindu gentlemen in satin, turbans, of knowing what no one else even pretended to know. You had only to ask a Hindu “What is death?” and he had an answer — an authoritative if cryptic answer, smug, ready-made and patronizing. It had always puzzled Bessie that these matters — immortality, ghosts, transmigration, healing — were not written down somewhere so that all the sick, suffering, questioning world might read and understand. Why must they be kept secret or imparted in parables by contemptuous Hindu gentlemen to eager American ladies with more money than wisdom?

Like everything else in life, it was slightly, vaguely disturbing. Better not think about it. When the time came to die she would probably take an express elevator to heaven and step out on a sort of roof garden overlooking the universe. Henry would be there, smoking and chatting with a lot of traveling men, and he would throw away his cigar to come toward her with his old line: “Well, Bessie, you’re ten minutes late.”

Ten years late, already! She wondered whether he would have forgotten her. There must be a lot of pretty women in heaven, and ten years is a long time. “I must exercise!” She was getting fat. Her legs were still good, but she had thickened through the middle. Her arms above the elbow were heavy. Pound by pound, ounce by ounce, through the greedy years she had filled out the lovely slim flanks of her and had surrendered her flexible waist to a certain rigidity, a look of being fixed within her stays. She no longer walked quite erect. Her garters pulled her forward a trifle and she had acquired the habit of looking down as once upon a time she had looked up, letting her pretty feet carry her where they would.

Nowadays she could not trust her feet, because they were much too small to bear her weight. She wore beautiful shoes, sheer hose, silk to the top, and it pleased her to watch their reflection in store windows or chance mirrors — her young legs.

“Breakfast, madame?”

“Oh, wait a minute! Wait a minute!” She struggled into a kimono. “All right, come in.”

As usual, she had her breakfast served on a table near the window. The hotel faced the bay. She could look out across the roofs of the city toward the ferry lanes, the fleet anchorage, and across the glittering water, to Berkeley and the hills. Straight down, nine stories, people walked in the square and strings of taxis moved up before the porte-cochère of the hotel. It was all very busy and purposeful and young. San Francisco was young. It was not a place to be old. It was a city for flappers and boys, roadsters, laughter, dancing, insouciant dreams and promises. Not a place for idleness like hers. And yet she loved it.

The very activity of the ferries delighted her — great shuttles crisscrossing back and forth, carrying people on endless, hopeful journeys across the bright water, in sunlight, beneath gay skies. She liked the fogs. She liked the steep, audacious streets, plunging down and leaping up, the screech of brakes, the patter of high-heeled slippers on asphalt set at acute angles. She liked the Orientals, the sailors, the flower venders. She was not a part of it, yet it animated her, kept her alive, made her aware of herself — her potential self that had never existed for Henry, that had been engulfed in poverty and postponement. Now, at fifty, she was rich and she was alone. Strange desires stirred in her — to be, for once, the Bessie who had never been.

“Nice day, madame.”

“It certainly is, George.”

“I brought madame a grapefruit.”

“Thanks…Oh, wait a second, George, till I get some change.”

“Yes, madame. Merci, madame.”

Mrs. Lovering spread the napkin across her knees and lifted covers, sniffing. Hot cakes, bacon, corn muffins. “I didn’t exercise. Well, tomorrow — ”

II

As she dressed she regarded herself with critical eyes. A fine skin. Henry had always said so. “A finer skin than yours,” he had said — “I’d like to see it. Show me Lillian Russell! Can’t hold a candle to you!”

She had always been told that she might be Lillian Russell’s twin sister. The resemblance flattered Bessie into pearls and a marcelled pompadour.

She saw now that her long, fine, silky yellow hair was old-fashioned. With a sudden breathlessness, as if she had plunged into cold water, she called the beauty parlor on the eleventh floor.

“Yes, please. . . A bob, a shampoo, a wave and a manicure. . . Mrs. Lovering. . . Ninth.”

There, in a gray-and-violet dressing room, beneath a shaded light and facing a mirror, she surrendered herself to a facile young man in a smock who held poised above her head the long scissors, the shears. She covered her face with her hands and a hot painful flush stained her cheeks.

“I don’t know!” she wailed. “Maybe I’m foolish. Maybe I’ll look a sight. Maybe I’m too old.”

Yvonne herself, in black satin, parted the curtains to look in upon the sacrifice.

“Too old, madame? One is never too old for the bob. Why, only yesterday I cut the hair of a great-grandmother! She said afterwards ‘Why didn’t I do it sooner?’ Honestly, Mrs. Lovering, you won’t regret it. Will she, Mr. Shaughnessy?”

“Positively not.”

The young man in the smock looked at Bessie in the mirror. His narrow, nervous fingers caught at the graying cascade of blond hair and lifted it, letting it fall again in a thin shower. He looked at her and yet did not look at her. There was an immense indifference in his eyes, an immeasurable weariness. It was the jaded disillusionment of the court barber, the initiated panderer to frivolity. Bessie would have preferred a Frenchman, a waxed flatterer who would have had at least the technic of deception. This young Irishman was too honest. He made her feel like a fool.

“Do her a short bob, Mr. Shaughnessy. Lift it here — so. Over the ears and back — so. A swirl. Just a little bang — ”

“Oh, no, not a bang! I look ridiculous in a bang.”

“Well, just a little spit curl. Madame’s forehead is high. You will see. You must have a permanent.”

“Not a permanent! My hair’s always been naturally curly.”

“To cut the hair reduces the curl. I will give you a permanent that will delight you–a big, soft, natural wave. Very fashionable just now in Paris — so — a swirl. So — Go ahead, Mr. Shaughnessy. I’ll come back.”

Yvonne was the last hold on sanity, on safety. The bright cold shears fell through Bessie’s hair — Bessie’s precious blond curls. Away. Away. Snip. Snip. A petal here, a petal there, as one strips a flower. There emerged the tearstained small face, the queer, round, denuded head of a stranger, the head of a blond rat.

“You ain’t crying? Say, that’s foolish. Crying won’t do any good.”

Mr. Shaughnessy pushed her head forward with strong fingers and attacked the nape of her neck. She felt the cold steel nipping there, biting off the little curls that Henry had called her love locks.

“What would the boys say?” she gasped.

“You got children, have you?” the barber asked.

“Two sons. They’re in Oregon, in the lumber business.”

“They got any kids of their own?”

“No,” she said. Thank God, she wasn’t a grandmother, shorn like this!”

“Say, I got a kid of my own!” Suddenly the scissors moved faster, with a furious industry and enthusiasm. “Born this morning at six o’clock. They let me see him. Say, maybe I didn’t run out to the hospital as soon as they phoned! The doctor was just leaving. He said everything was fine. So I went in and the nurse showed me the baby. Say! A girl! Not red, like most of them, but white, like — like a white rose. Not crying or anything. The prettiest mouth — ”

“Aren’t you getting it a little too short?”

“Eh?”

“My hair.”

“Say, maybe I am. You don’t have a baby every day in the week, do you? It’s no wonder I’m nervous. My wife’s only eighteen. Molly her name is. She was just over from the old country when I met her — didn’t know a thing. Now she’s the best little American you could hope to find… Turn your head a little. Did you want this wind-blown?”

“Wind-blown?”

“Say! Yvonne!”

Yvonne’s black satin presence, her absent-minded enthusiasm, again dominated the mirror.

It was at the coiffeuse and not at herself that Bessie looked for confirmation of her fear. She saw the sly, amused and cruel smile she dreaded, an instant before it was erased, supplanted by flattery.

“You look ten years younger! Doesn’t she? Marie, come here! Joyce, come here at once! I want you to see Mrs. Lovering’s new haircut. Isn’t it charming?”

“Yes, awfully becoming, Mrs. Lovering.”

“Isn’t it youthful?”

Yvonne seized a comb and raked at the shorn locks deftly, combing them violently forward, then aside and back, curling with little pats and subtle twistings.

“You look like your own granddaughter. Look at yourself! Here, Joyce, give me a mirror. Now look! When you’re waved you won’t know yourself. Silly girl, you’ve been crying. Marie, Mrs. Lovering’s been crying! And she’s so sweet and pretty! Why, honestly, you look like Lillian Gish with this cut. Such small features. Here, I’ll wave you myself.”

Out of her great mercy, Yvonne wielded the irons. There emerged a series of neat undulations placed with such skill that Bessie’s blond hair resembled, in its perfection, a wig. She gazed upon herself at first with horror, as at an intimate stranger in a nightmare; then, slowly, she caught the fever of the place — it burned within her. The three young women, laboring with whispered words of encouragement, evoked a new image. She began to like this reflection. A facial, the stinging application of tonics, ice, lotions, more ice, removed the traces of her cowardly tears and gave to her flesh a glow and a firmness of youth. Her hands, buffed and tinted by an anemic child with shadowed eyes and scarlet, petulant mouth, had the luster and pointed elegance of the waxen hands of a show window dummy. Her rubies caught the fire and struck a sullen, dark envy in the shadowed eyes of the manicurist.

“You have pretty hands, madame. Nice cuticle. You ought to use our Pond Lily Cuticle Cream. It’s very nice.”

At last Bessie rose. Yvonne said: “You must come for a reset on Tuesday. Let me see — the total — just twenty-seven-fifty… Thank you…Good morning. You look wonderful!”

III

She lunched with Mrs. Struthers and Callie Frisbuth in the Green Room.

“Bessie Lovering, don’t tell me your hair’s bobbed!”

“It certainly is. And I wish I’d done it ten years ago.”

Mrs. Struthers was like a black rabbit nibbling at invisible lettuce leaves. In her quick dark eyes there was always the look of an impending criticism; she seemed, even when most affable, prepared to pounce. She implied now, by an ostentatious silence and the flicker of a smile at Callie Frisbuth, that she thought Bessie’s haircut ridiculous.

Callie Frisbuth said: “I think older women are more dignified with long hair. And after forty, goodness knows, there’s nothing much except dignity left for us women. It’s terrible, disgusting, the way youth rules the world.” She sighed. “I feel so out of it.”

“Well, I don’t,” Bessie said, flashing her rubies over the bread and butter plate. “I feel younger than ever. I’d like to go to the football game in Berke this afternoon, instead of playing bridge with a lot of old women.”

“Well, I must say we’re flattered!”

“I mean it. I’d like to dance. I’d like to sit up all night. Old lady? Pooh! I’m just beginning.”

“Maybe you’ll marry again,” Callie Frisbuth, who was not married, said, tightening her lips.

“Maybe I will.”

“I think,” Callie Frisbuth said, “a woman with children — grown children like yours — is happier a widow. Second husbands are seldom a success. I mean as stepfathers.”

“But I never see my children! They’re too busy and too ambitious to need me. They’ll be marrying soon and starting lives of their own — children of their own!”

“I thought you cared a great deal for Mr. Lovering,” Mrs. Struthers said.

“I did — I do. But Well, sometimes I’m lonely. Evenings — ”

“A lot of us are lonely evenings,” Mrs. Struthers snapped. “You’d better keep your head, Bessie. Just because you’re bobbed, you aren’t any younger. At fifty you’ve got to see things as they are.”

Things as they are!

Something had happened to Bessie Lovering. The bridge tables in Mrs. Taylor Smith’s house on Russian Hill seemed to be too close together; the rattle of women’s voices, excited, angry, hysterical, anxious, beat on the eardrums like a savage tom-tom. So many ample bosoms; so much navy-blue crêpe de chine; so many pearl earrings and chokers and fox neck pieces. Rich women, idle women; women in the forties, the fifties, the sixties.

Suddenly Bessie wanted to be away. She did not wait for tea. The prizes — embroidered squares never to be used as chair backs — were distributed. Little heart shaped caviar sandwiches, ovals of lettuce, elliptical cakes and mounds of quartered toast. Coffee in thin, cream-colored cups. Pistachio ice cream. “But I’m reducing!” “Just one!” “If you count your calories religiously, my dear — ” Whipped cream, cherry tarts, cheese straws, salted nuts. “I won’t eat a bite of dinner.” Chopped olives. Shortcake. “M-m-m — good — Now don’t you look! I’m going to take just a little piece.”

From the windows, Bessie could see the bay and the ferries. Suddenly, passionately, she wanted to be in the bright, crowded stadium, to see youth heaped up in great yelling pyramids — youth riotous, joyous, unaware. She wanted to plunge herself in sunlight and color and noise.

“I guess I’ll buy a dress.” She slipped out and into a taxi. Her cheeks were flushed. Her neck, where the fur piece fell away, seemed naked, stripped. She said “Downtown.” And putting up her hand, felt the unaccustomed shortness above her ears, the brittle, singed, clipped curls against her cheeks.

She craved the satisfaction of spending money. An evening dress — something to dance in. She danced well. Like most heavy blond women, she was light on her feet. She wondered whether Henry had learned the fox trot and the Charleston in heaven. Henry could one-step with the best of them. Once, to her amazement, he had mastered the bunny hug. Funny old Henry! Henry, whose money made it possible for her to be comfortable all the rest of her days — comfortable, safe and alone!

“Oh, Mrs. Lovering, I have the most lovely new model! Just made for you. I said, the minute it came in, There’s Mrs. Lovering’s dress!”

This shop catered to the hypothetical superiority of its clients — walnut and brown velvet, rose brocade and shaded lights, but no show cases, no price tags, no obvious barter.

The saleswoman, clad in fluttering ends of chiffon, slim, even, frankly, emaciated, trod the sacred velvet with the mincing, impeded grace imparted to the female gait by undernourishment and spike heels. She was pale; her gray eyes held a gentleness and a sad frustration. She was elegant and meticulously grammatical. Her manners, even at five o’clock of a confined and distressing day, were without flaw or strain.

Bessie said, “I want an evening dress and a wrap.”

“Ah, yes, at once. I have just the thing. Something simple but important. Miss Adams, will you model the little white gown for Mrs. Lovering?”

Bessie sighed and waited. She was conscious of a curious sense of defeat, perhaps a reaction from the excitement of the morning.

“You look tired, Miss Peters,” she said.

The saleswoman leaned against the mirrored wall; she put her hands against her back; she drooped. “I am. I’m awfully tired — awfully tired.”

“Why don’t you sit down?”

“We’re not allowed. But sometimes my back aches so — ” She smiled. “Life isn’t easy, is it?”

“How old are you?” Bessie said.

“Twenty-two. But I feel fifty.”

“Why don’t you get married?”

Miss Peters caught her breath. “I’d like to, but my fellow’s out of a job. He’s a newspaperman. He’s broke. And I got poppa to do for… Sometimes — I get so tired just waiting, Mrs. Lovering — ”

“I know.”

“Waiting for happiness, waiting for a home, waiting for children of my own.”

“But you’re young.”

“What good’s youth?” The pale girl flung her head back, straining her throat until the muscles showed, taut and tortured. “What good’s youth to any of us? We’re throwing it away, making slaves of ourselves.” She caught her breath. A look of terror, of extreme deprecation, came into her eyes.

“Oh, Mrs. Lovering, forgive me! I forgot myself… Ah, Miss Adams, the little white dress! Very chic. Very new. A model. So youthful. So distinguished. The little wrap too. Together, the price is — let me see — five hundred and sixty-three — reasonable, don’t you think?”

IV

Bessie shook her head. “It’s too much, Miss Peters. But I’ll take it. I have a very special — a very special engagement tonight.”

She imagined herself going to a dance. The idea, conceived out of her great need, assumed an astonishing reality. She plunged into an orgy of buying — underwear, stockings, a little beaded bag, a frothy handkerchief, a necklace of crystal, a flower of transparent gauze, exotic and perishable.

Miss Peters ran back and forth on stilted heels. The party, Bessie’s very special engagement, animated the pale girl. She imaged a beautiful ballroom, people moving across a polished floor, music, flowers, happiness. Her cheeks flamed with excitement. She spread the flimsy lengths of chiffon and lace for Bessie’s inspection, but, in her heart, she herself was going to wear them. She saw herself in the arms of her lover, whirling gracefully, slowly, to the languid measures of a waltz, her cheek close to his, his dark head bent to hers, whispering, “I love you. I love you.” Their feet reflected in the polished floor. Chandeliers ablaze with light. Mirrors. Laughter. Roses. The fullness of heart that is realization.

Bessie, too, saw herself arrayed for happiness. Yet, by a curious reversal, she wore in the confusion of dream and fact the gown of another period — she saw herself in the full satin skirt, the tight bodice, the great, flaring sleeves of yesterday, pompadour, a sheaf of American Beauties, long kid gloves, a train; and Henry, baggy, shining, gentle, waiting at the foot of the stairs.

“Well, Bessie, ten minutes late!”

“Ten years late!”

“Beg pardon, madame?”

“I was thinking out loud.”

She stuffed herself and her packages into a taxicab. Already the streets were dark. The shops were closing. Cable cars were incrusted with people.

The lobby, when she crossed it in the wake of a laden bell boy, was animated, crowded. The victorious collegians swept through in a wave of color and laughter to the dining rooms. Girls and girls and girls. Slim silk-clad legs, like the legs of colts. Hats worn on the back of the head, revealing bland foreheads and wide, brilliant eyes. White teeth. Smooth round chins. Fur jackets and brilliant silk handkerchiefs. The laughter of girls. The hope of girls. The inestimable, precious illusion of girls — thousands of girls…

The bell boy preceded Bessie down the carpeted corridor to her door. He bristled with boxes and packages. He whistled softly. He was a nice boy, a polite boy, and Bessie fumbled in her bag for a tip.

“Put the bundles on the bed.”

“Yes, ma’am.” He obeyed with a flourish. “Shall I light the lights?”

“If you please.”

Already the loneliness, the silence of the room, made itself felt. Bessie turned with a shudder from the proofs of her extravagant folly.

“Going to the dance, Mrs. Lovering?”

“What dance?”

“The Stanford crowd’s here tonight. It’ll be a riot.”

“No,” she said, “I’m not going. I haven’t anyone to go with. I’m alone.”

The bell boy accepted her tip and pocketed it. Yet he hesitated.

“Say, Mrs. Lovering, if you’re alone — it’s like this: I’ve got a friend — a nice fellow, see? An Italian. His name’s Bellardi. He dances like a million dollars. He’d take you out, anywhere you’d like to go.”

“You mean I’d have to pay him?”

“Sure! It’s his business. He’s a good guy. Well-behaved, see? And a swell dancer. He knows the ropes. I could get him for you.”

Bessie’s hands trembled. “How much does he ask?”

“Twenty-five for the evening, and expenses.”

“He speaks English?”

“Sure! He was born in the Napa Valley. His father has a ranch out there. They’re wops. But you’d like him. No use your being alone Saturday night. Gee, it’s awful up here! What you need is a little life, see? I wouldn’t mention it, only I guess you’re lonely — I’ve noticed it. I said to myself often, Bellardi’d ought to take Mrs. Lovering out and show her the sights.’”

“He’s — he’s young?”

“Not too young — thirty. He’s a good guy and a grand dancer. You wait and see.”

Bessie glanced again at the parcels. Her flesh yearned toward adornment — to wear the white gown and the wrap and the flower!

“Very well,” she said briefly, “send him up at 8:30.”

The boy smiled. It was impossible to interpret the smile. Bessie was both disturbed and curiously gratified. She was partner in a conspiracy. She was, actually, engaged in a questionable undertaking. She was about to do an outrageous thing. She had stepped out of the impeding four walls of her respectability. The bell boy shared her secret. He smiled. She grew hot all over.

“I’ll be ready,” she said. She stopped him on the threshold. “And please don’t mention this to anyone. You understand?”

She turned to the boxes. She emptied them with hands that shook.

Seven o’clock! She ran into the formal stuffy sitting room and put it in order. Fresh flowers, thank heaven — Callie Frisbuth’s carnations and Mrs. Struthers’ roses. “On our dear Bessie’s fiftieth birthday, from her pals and fellow ancients, Callie and Evangeline.”

Back to the bedroom. A bath. Crystals. The pungent, aromatic sweetness of lavender and cologne. Her nice feet and legs. Her white flesh. Clouds of powder. Silk and lace. Tight satin stays. Cream. Lotion. Ice. Ouch! Cold! Powder. Rouge. Maybe a little eye pencil. Her funny hair.

She was going to a party! What would Henry say? She could take care of herself. Henry would say, “Go ahead and have a good time. You deserve it. You’ve been a good woman.”

She rang for the maid, but for some reason — perhaps the influx of victorious collegians — there was a delay. While she waited she scrutinized herself. She was almost beautiful. Something had come back into her face that had not been there for ten years — a look of expectancy.

“Yes, madame?”

“Will you help me with my dress?”

“Certainly, madame.”

This was a veritable wisp of a maid, a child in the uniform of servitude.

“I suppose you’re very busy tonight.”

“Yes, madame. I have the night duty. I’m on until two o’clock.”

Bessie ducked her shorn head and received the glittering white shift. It fell along her body like ice, clung heavily. The maid’s fingers touched the crystals lovingly; she fastened them about Bessie’s throat.

“Oh, lovely, madame!”

“Yes, aren’t they pretty?”

“And the flower?”

“Here on the shoulder.”

“You look very nice, madame.”

“Thank you. Will you powder my back and arms?”

“You have very nice skin, madame, for a woman of your age.”

Why did the girl have to say that? It wasn’t kind. She was cruel because she was young.

“Thank you, madame… Good night. I hope you have a very nice time.”

Bessie faced the mirror. She could not believe that this glittering creature was herself. When the telephone rang she shivered all over and her lips stiffened, grew momentarily cold.

“Mr. Bellardi to see Mrs. Lovering.”

“Send him up.”

She waited, fingering Mrs. Struthers’ roses. Her heart beat furiously. She thought: “I’m a fool. I’m a coward. I’m lost. What shall I say to him? How shall I pay him? Perhaps I’d better send him away.” She was frightened and exalted.

When the knock came at the door she could scarcely say “Come in!”

V

He proved to be not the dark overdressed dressed Italian she had fancied, but, rather, a neat, well-brushed young man, a sober young man. There was nothing racially characteristic about him save his black hair and eyes. He had the short straight nose, the quick smile of an Irishman.

“How do you do?” she said.

“Mrs. Lovering? My name is Bellardi. My friend Charlie sent me” He paused.

“I know. What arrangement — I mean, how do I pay you? Now or when we return?”

He smiled. “Well, it might be better now, if you don’t mind. I haven’t a cent.”

“Would fifty dollars — ”

He stepped brightly into the room. “That depends,” he said, “on what you want to do. Dinner? Theater? Some nice dance club? And then to the beach? Wine? Cabs? I should say seventy-five at least.”

“Very well, we’ll do everything. I’m in your hands.” She fumbled in the new beaded bag for the crisp price of her enjoyment. “My sons,” she said, “would be grateful — ” She could not go on.

“Sure. I’ll take good care of you. I never go where there’s anything rough. You trust me… Thanks.”

He pocketed the bills without glancing at them. He was neatly dressed; but he had no overcoat, and the gray informal hat he carried was old and faded. The bell boy had said that he was thirty years old; he looked younger. He had the fresh color, the strong white teeth of a boy of twenty.

“Your wrap?”

The formalities over, he became all at once the cavalier. With a flourish he placed the wrap upon Bessie’s shoulders. In the gesture there were both homage and grace without a trace of insincerity. He said nothing, but in his glance, as he held the door for her, there was admiration, a look personal and appraising and strangely pleasant. It had been ten years since anyone had noticed Bessie Lovering herself. The last thing Henry had said to her was her last unsolicited compliment: “You’re a handsome woman, Bessie. When I’m gone don’t wear black. You look better in colors.”

The elevator, already crowded, paused for them, and Bessie squeezed in beside Evangeline Struthers and Callie Frisbuth. Their startled eyes flew from Bessie’s magnificence to the dark sleek head of her tall escort.

“Mrs. Struthers, Miss Frisbuth — Mr. Bellardi.”

“How d’you do?” they said.

Mrs. Struthers pinched Bessie’s arm. “Who is he? Who is he, Bessie?”

“We’re going to the opera,” Callie offered. “Martinelli in Aida. We have a box.”

“Won’t you come, Bessie? Won’t you and Mr. — and Mr. — I didn’t catch the name — won’t you join us?”

Bellardi gazed politely into Bessie’s eyes. He seemed to suggest that he preferred to be alone with her.

“No, thank you, darling,” Bessie’s voice lifted. “We’re going to dance.”

The door opened and she swept out, Bellardi at her elbow. Now for the first time she was a part of the animated crowd in the lobby, as if, by the simple alchemy of short hair and an escort, all the lonely years had been erased. She no longer envied the gazelle-like girls of the lobby; she loved them. She was one of them. She was going to dance. She was going to dance!

A cab slid along the curb, but Bellardi rejected it for a rakish machine whose driver signaled to them with the smirk of a self-conscious wrongdoer.

One of Bessie’s crisp bills changed hands and she found herself upon the velvet cushions of someone’s town car, gazing upon the city through immaculate plate glass. A transformed city — a city marvelously gay, mysterious, promising. All the faces glimpsed in passing wore the masks of revelry. The crowds dissolved and clustered, lively figures in a pageant, and the leap of traffic between lanes of light was strangely exciting, exhilarating, like a race in a carnival. Bessie glanced down at her frivolous silver feet, at her tinted hands, her rubies, never so darkly bright as now. She had forgotten Bellardi. It had seemed for a moment as if Henry rode beside her.

“May I smoke?”

“Of course.”

The young Italian produced a battered package of cheap cigarettes. He offered Bessie one.

“No, thanks, not now.”

Promptly he quenched his own.

“Where are we going?”

“To the opera. No? Martinelli in Aida. We will show your friends that we, too, can sit in a box.”

“But I haven’t had dinner!”

“We will have coffee there, and later dine properly. Leave all to me.”

She found herself upon the inadequate chair offered to patrons of the opera. Bellardi removed her wrap. He drew his chair forward to the rail, gazed down at the orchestra pit, where, in the sudden darkness, a twitter of sound arose. The opera had begun.

Bessie did not like music. It was apparent that Bellardi did. He put his chin in his clenched hands and remained immovable, entranced, hypnotized until the end. Save for a brief promenade, when he offered her a cup of weak coffee in a thick cup, he did not speak to Bessie.

“I like Verdi,” he said. “I am Italian. It is in my blood. I am starved for music. This is food for me. Beefsteak? Not when I can hear Martinelli sing! A big voice — that fellow. My father knew him, long ago, in Venice.”

When they left the opera house he seized Bessie’s arm. “I tell you what! In honor of Martinelli, we dine and dance at the Casa Veneziana. What do you say?”

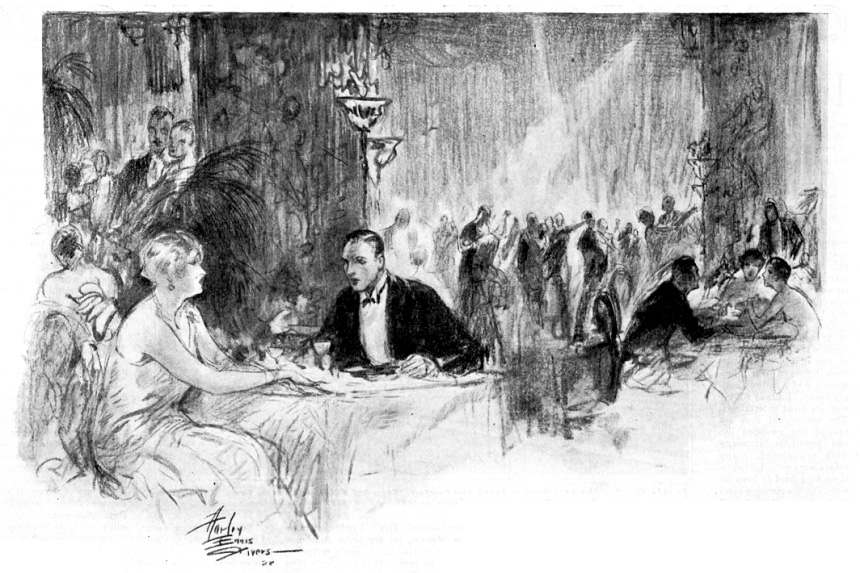

The Casa Veneziana was a long way downtown. Another motor, commandeered at the point of a ten-dollar bill, swept through the tunnel, followed a strange boulevard, climbed a dizzy cobbled hill and left them before a doorway flanked by gilded barber poles. They entered upon a wave of sound, a frantic confusion of voices, music, whistles, laughter and the rattle of crockery. The head waiter, clad in white duck and tightly girdled, wore upon his glistening bald head a tasseled fisherman’s cap.

Bessie’s white sequins turned blue in the light of many purple arcs. For this was a Venetian grotto. A semicircle of tables surrounded a dance floor flooded with artificial moonlight. Gondoliers of many nationalities threaded the maze with trays and glasses. Spaghetti, borne aloft upon perspiring palms, left a trail of appetizing odor. Coffee splashed from kitchen to table. Minestrone. Ravioli. Fritto misto. Thick slices of dark bread. Romanello. Bessie felt faint with hunger.

She thought, following Bellardi through the noisy crowd, “This is life. I ought to like it. At least I’m not alone.”

She would have preferred a hotel, the discreet dance floor and shaded lights of some Rose Room or Crystal Hall.

She found herself at a table close to the stage, where an orchestra, seated within a vast funereal gondola, played Hallelujah.

“Shall we dance?”

Bellardi placed his hat upon the table — by way of identification perhaps. He said, “Keep your wrap. It isn’t safe to leave it.” And embracing her, he drew her out on the floor. Perhaps Aida had gone to his head. His eyes were bright. His mouth smiled. He had the look of a faun. And he could dance. He seemed to float across the floor, insinuating his way, surely, carelessly, expertly, between the jazzing couples. Bessie’s head had no idea what her feet were doing. She felt the pressure of his hand upon her back; he guided her with a gentle, firm touch, a command, a whole book of instructions. He moved without effort, holding his head high, smiling his smile of a faun — or was it the smile of a little boy who has just eaten a lollipop?

Colored lights swept the dance floor in rotation. Purple. Blue. Yellow. Green. Red. Purple. Blue. Faces, grinning or absorbed or ecstatic,appeared now blanched, now flushed, now a sickly green. Bodies pressed close. A kaleidoscopic whirl of people danced in Bessie’s eyes. Her feet were scuffed upon. Table after table was deserted for this mad revivalist music. Hallelujah! Hallelujah! Helps to shoo th’ blues away! Satan lies a-waitin’ and creatin’ sin and woe, woe, woe! Sing Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

She felt Bellardi’s smooth hard cheek against her own. He paused, hummed, swayed, began the intricate swishing steps of the Charleston. Bessie’s heart felt funny. “Either I’m hungry or I’m old.” The wheeling faces blurred, grew dim. “Please,” she said, “stop! I’m going to faint.”

VI

Bellardi fanned her with the menu card. “You’re hungry, that’s all. Have some water. The waiter’ll be here in a minute with some onion soup. Food’s what you need.”

“I haven’t danced for ten years.”

“You don’t say! You dance well too. You dance like a young girl. For a heavy woman, you’re light on your feet.”

“And you,” she said — “you dance like a professional.”

“I’m not,” he said quickly. “I’m a newspaperman out of a job.” Suddenly he leaned across the table, smiling a queer, crooked sort of smile. “The truth is, Mrs. Lovering, I’ve never done this before.”

“Done — what?”

“I’m not a hired dancing man — the sort of fellow they call a gigolo. Charlie put me up to this. He knew I was broke. When he sent for me I said no. I couldn’t picture myself hauling an old woman around and being paid for it. But he said you were different. He said you were a nice woman — just lonely. And I don’t blame you. Gosh! I understand. It must get terrible up in that hotel room, with nothing to do and nowhere to go.”

“It does,” she said.

Her heart was still now; it seemed not to beat at all. Only the nerves on the surface of her body quivered and jumped and the roof of her mouth was cold. There was pain behind her eyes. Too many people! Too much noise! Balloons popped and wooden sticks whacked. Paper streamers zinged and tangled. Shrieks of laughter collided with the shrill blasts of tin whistles. Three men in velvet jackets entered the spotlight and sang — Santa Lucia. No one listened. Soup. Cheese. Coffee. Smoke, stinging, acrid. A policeman, leaning against a barber pole, watched the crowd.

“I’m sorry,” Bessie said.

“I’m not.” Bellardi again offered her a cigarette from the tattered package. She shook her head. And again he quenched his own, as if rebuffed by her refusal. “I’m not. I’ve enjoyed it. Maybe, tomorrow, I’ll feel better… Aida! Say, that music cut clean into my heart and scooped out a lot of self-disgust! Maybe tomorrow I’ll get a job. And believe me I need it. I’m broke. I hate to take your money for this, but I’m hungry. That’s a fact. I won’t go to my father. He wants me to be a farmer. He thinks writers are sissies.”

“How old are you?”

“I’m twenty-three.”

“Twenty-three! I’ve got a son twenty-eight!”

He glanced at her with a quick dark look of sympathy. “It’s a shame you don’t live with him,” he said.

“He’s going to be married.”

“So am I. . . . Say, Mrs. Lovering, she’s a peach. You ought to see her. And bright? She’s a whiz. Only twenty-two, and already she’s the crack saleswoman at Magnow’s French Shop. Going to be a buyer. Takes care of her dad and a kid sister. Her name’s Peters — Lila Peters.”

Two and two were making four in Bessie’s mind. She said “Give me a cigarette, please.”

“Sure!”

He leaped, the match glowed. For the first time she tasted the thick bitter smoke. Tobacco flakes clung to her dry lips. But she persisted, because, in her mercy, she sensed this boy’s need and his hunger. Smoke poured through his nostrils. He tipped his head back, opened his mouth and let the fumes curl along his tongue.

“She and I ought to be doing this — dancing and hearing music. We’re wasting our youth. We’re missing everything.” Gosh! It doesn’t seem fair.” He leaned forward again, clasping his hands, the cigarette balanced between his lips. “You understand, don’t you? You’re a mother. I guess you loved your husband. Sometimes I think I’ll go crazy. Lying alone in my room, thinking about her lying alone in hers — and my heart crying out loud!” He grinned. “I sound like a Dago, don’t I? Well, I am. It’s in my blood. When I love, I love hard. Lila too. She’s getting thin. She can’t sleep. And if she knew I was doing this — ”

Bessie put out her hand and laid it briefly, firmly on his. “You’re my guest. I know Miss Peters. She sold me this dress. I paid eight hundred dollars for what I’ve got on.”

“Your guest?”

“I’m old enough to be your mother. I’m heart-hungry myself. And I’m not a Dago. I’m Boston Irish. My name was Bessie Calahan.”

She ground the cigarette out in a glass dish, forgetting to flash her rubies.

“Listen! Evangeline Struthers’ grandfather owned the first newspaper ever published in San Francisco. Her father owned two more. Her husband owned a whole chain of them, from Seattle to Mexico. I guess she can find a job for you if you want one.”

Before the look in his eyes — a stark look, somehow blinded and confused — she blinked and rose. “I want to go home, please — quick. Pay the waiter and don’t wait for change. I’m tired.”

VII

She left him in the lobby and took the elevator to the ninth, alone. The carpeted halls were dimly lighted and silent. Only the black skirt of the little maid flitted around a corner and disappeared.

“I’m tired — tired.”

She closed the door of her bedroom softly, as if upon a sleeping dream — a dream not to be awakened, a dream that must not be disturbed.

She kicked off the tight silver slippers, dragged the heavy dress over her head, rubbed at her cheeks with a towel. Water — lots of it. Soap. Clean — clean. That’s better. A comb through the brittle blonde curls. Henry would say: “Well, now you’ve done it, let ’em grow again. I like you best with it long. Lillian Russell — that’s your style.”

Henry! Henry! Where are you?

The maid had turned back the corners of the bedclothes and had placed with dramatic effect the crêpe de chine nightgown, that fragile, extravagant bit of fluff, hemstitched, pin tucked, girdled with knotted strands of baby-blue ribbon. Beneath it, pigeon-toed, a pair of blue satin mules. On the pillow, a cap of crocheted silk to put over her hair.

Bessie gathered these things up and threw them on the sofa. She went to the bureau and found, neatly folded, slightly yellowed and crumpled, a nainsook nightgown with sleeves. It was trimmed with Cluny lace. It was ample and soft and clean. She put it on.

There were slippers, too — comfies with silk pompons on the toes. Arrayed thus, with her hair slicked back and a soaped, shining countenance, she felt somehow protected. She pulled the blinds against the lighted city and knelt by the bed.

Illustrations by Harley Ennis Stivers

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now