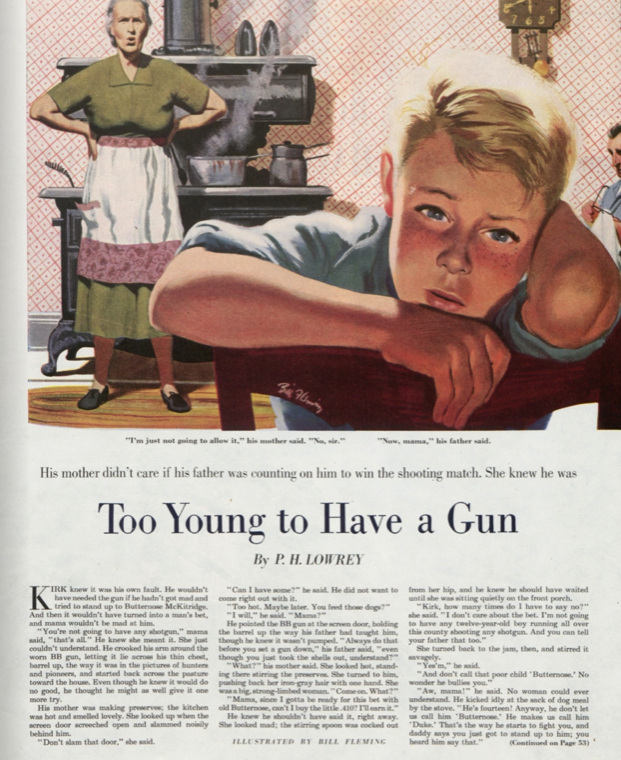

Perrin Holmes Lowrey wrote a handful of poems, articles, and short stories for various magazines in the 1950s. Some of his most popular works include “The Great Speckled Bird and Other Stories” and his O. Henry Award winner “Too Young to Have a Gun,” a captivating tale of a young boy balancing the challenges of adult responsibilities.

Published on October, 11, 1952

Kirk knew it was his own fault. He wouldn’t have needed the gun if he hadn’t got mad and tried to stand up to Butternose McKitridge. And then it wouldn’t have turned into a man’s bet, and mama wouldn’t be mad at him.

“You’re not going to have any shotgun,” mama said, “that’s all.” He knew she meant it. She just couldn’t understand. He crooked his arm around the worn BB gun, letting it lie across his thin chest, barrel up, the way it was in the pictures of hunters and pioneers, and started back across the pasture toward the house. Even though he knew it would do no good, he thought he might as well give it one more try.

His mother was making preserves; the kitchen was hot and smelled lovely. She looked up when the screen door screeched open and slammed noisily behind him.

“Don’t slam that door,” she said.

“Can I have some?” he said. He did not want to come right out with it.

“Too hot. Maybe later. You feed those dogs?”

“I will,” he said. “Mama?”

He pointed the BB gun at the screen door, holding the barrel up the way his father had taught him, though he knew it wasn’t pumped. “Always do that before you set a gun down,” his father said, “even though you just took the shells out, understand?”

“What?” his mother said. She looked hot, standing there stirring the preserves. She turned to him, pushing back her iron-gray hair with one hand. She was a big, strong-limbed woman. “ Come on. What?”

“Mama, since I gotta be ready for this bet with old Butternose, can’t I buy the little .410? I’ll earn it.”

He knew he shouldn’t have said it, right away. She looked mad; the stirring spoon was cocked out from her hip, and he knew he should have waited until she was sitting quietly on the front porch.

“Kirk, how many times do I have to say no?” she said. “I don’t care about the bet. I’m not going to have any twelve-year-old boy running all over this county shooting any shotgun. And you can tell your father that too.”

She turned back to the jam, then, and stirred it savagely.

“Yes’m,” he said.

“And don’t call that poor child Butternose.’ No wonder he bullies you.”

“Aw, mama!” he said. No woman could ever understand. He kicked idly at the sack of dog meal by the stove. “He’s fourteen! Anyway, he don’t let us call him Butternose.’ He makes us call him `Duke.’ That’s the way he starts to fight you, and daddy says you just got to stand up to him; you heard him say that.”

He knew he ought not to go on with it, but he had to make her understand somehow.

“Stop it,” she said, and he thought she was going to turn and really give it to him. But then he saw that she was trying hard not to smile, so he knew it was all right.

“You’re smilin’,” he said.

“Oh, stop it! “ she said, but he could see now she was almost laughing. He knew he would have to work fast.

“It isn’t funny,” she said, trying to look mad. “ It’s a sin before God.”

“You can’t stop laughing,” he said, grinning. “You think I’m a limb of Satan.” That did it. She had to laugh then. He liked the way she laughed suddenly.

“Get on out of here and feed those dogs,” she said, still laughing. “And stop lawyerin’ around about that gun. You’re worse than your father!”

“All right,” he said, “but it’s a man’s bet.” He went out fast so she could not say anything more to him.

While he fed Bump and Pompey, crooning to them in the high tone he reserved especially for them, he thought about it. The dogs were in good shape now, lean and hard. He had trained them well, but he was still afraid they were no match for the McKitridge dog, Blue Mike. Blue Mike was a pointer, too, but very tall and big-muscled, even for a McKitridge dog. When he looked at Bump and Pompey and compared them, it scared him a little. He could remember the first time he had ever seen Blue Mike work, and that had been a little frightening too.

He came across a ridge late one afternoon and looked down into the next bottom and saw Old Man McKitridge. For a moment, he did not see the dog. Then he looked far out ahead of Old Man McKitridge, and saw the flat, uncoiling white shape, going away in a perfectly straight line. As he watched, the dog turned and quartered back, still moving in that odd straight line, going very fast. He saw Blue Mike slide diagonally across the field and then drop to a dead point in one corner, standing there like something in marble until Old Man McKitridge came up slowly. It took a long time. After the shot, the dog retrieved fast and was gone again, covering the field in long, stretchedout strides, so that he knew it was a big dog before he ever saw it close up.

He opened the chicken-wire door of the dog run when Bump and Pompey finished. Each day now, he let them run after he fed them. He fed them only once a day now, though it was only October. When they finished wolfing the food, he ran them, stopping them occasionally to make them come back and go to heel.

They passed him again, running head to flank, starting on around the house, and he let them get clear around before he called.

“Hyah!” he yelled, and he heard one of them smack into the other and hit the ground, so he knew they had turned. When they came in, he made them follow him to the turtle pen where he kept the snapper.

“Come on, Snapper,” he coaxed, prodding at the squat heavy shape of the turtle with a stick. “Come on!” The turtle’s malignant eyes followed the prod a moment, and then, without warning, the big snakelike head slammed forward viciously. He prodded again, watching the turtle’s open beak carefully. Bump barked and began to lunge at it.

“Git back! “ he commanded, kicking at the dog with his bare foot. “ You let Snapper get your nose, you won’t hunt anything, you fool.”

He kicked listlessly at Pompey, too, to keep him back from the turtle. He did not feel like working them today, because he was too worried about Butternose and the gun. He wished he had gone on and fought Butternose, right at first when it happened, even though he knew Butternose would have licked him.

He had gone into town early that morning, to Callicutt’s store. Mr. Brannan, the night watchman, was kidding him about the dogs.

“What kind of dogs are they, Kirk?” Mr. Brannan said, smiling out of one corner of his leathery face. “They bird dogs or boy dogs?”

He grinned, because Mr. Brannan always kidded him about the way the dogs trailed him on the bicycle.

“I seen ‘em come sniffm’ through town here, about thirty minutes behind you, the other day,” Mr. Brannan said, “ goin’ hell for leather. Callicutt,’ I said, ‘I reckon them things would follow that-air train right to Memphis if Kirk took a notion to get on it.’ They certainly are good train dogs.”

“I like ‘em,” he said; “ they’re good dogs.”

“I reckon so,” Mr. Brannan said. “Didn’t I see ‘em point that boxcar the other day, when you was in it? I know they’re good.”

He watched Mr. Brannan go on back to the rear of the store, to the dark little counter under the mule collars and farm tools, where the men sat and talked and occasionally slipped the bottle of white whisky up to their lips. He liked it when Mr. Brannan kidded about the dogs.

When he went out the door, Butternose had little Rat Rickert by the neck, holding Rat up against Callicutt’s window. Butternose’s meaty face, with the peculiar squarish nose glistening and pitted, was close down to Rat’s head. He could see Butternose’s hand working into the soft flesh of Rat’s neck.

“What’s my name now, Rat?” Butternose said.

“Duke,” Rat said, trying not to show how it hurt. “Duke, Duke, Duke!”

“Don’t forget it no more,” Butternose said, working his fingers in again.

“O.K., Duke!” Rat gasped, and broke free. He could see the tears held back in Rat’s eyes, and he was scared then, because he knew what he was going to do. He wasn’t surprised when Butternose grabbed his arm.

“Well, skinnybone,” Butternose said, holding his arm tight, “now you tell me my name.”

“Fred’rick McKitridge,” he said. He could tell from the way Butternose flexed his knee that it was going to be a corn.

“My nickname,” Butternose said. He was about to say “Duke” when the knobby knee came up quick and sharp, just once, into his thigh.

“Butternose!” he said, because the pain of the corn had forced it out of him. “Butternose, Butternose!” He wrenched free and jumped back with his fists up.

He had a minute to get set, because Butternose stood there staring at him. He swung once, and felt his fist hit the shoulder; something jerked his head back and he was swinging as hard as he could, and he felt the red-hot knee again, and then he didn’t seem to be hitting anything. When he opened his eyes, Mr. Callicutt had Butternose by the scruff of the neck.

“Same breed as your old man, ain’t you, McKitridge?” Mr. Callicutt said, his voice very soft and furry. “Only he don’t spoil for trouble till he’s drunk.” Butternose still looked surprised. “You ain’t gonna beat nobody half your size in front of my store.”

By that time the men had come out of the store too. Mr. Brannan; Amos Beesinger, who was part Indian, and in whose face you could still see the high cheekbones and flat nose of the race; Sheriff Kent and two farmers. He could not remember how the bet started, because he was still too mad and his jaw had begun to hurt. But he knew Mr. Brannan suggested it. He listened, and he knew he had missed some, but what Mr. Brannan said was clear.

“Now, Kirk here likes to hunt,” Mr. Brannan was saying, “and you McKitridges is pot-hunters. Kirk’s got him some dogs. I reckon a shootin’ match would be right fahr, now I think on it.” Mr. Brannan looked over at him carefully. “You ought to agree to that to settle it. Kirk ain’t never gonna have flesh to fight you, and you got all them fine dogs, and all.”

“Him!” Butternose was saying then. “ Him! Hell, he ain’t big enough to tote a gun, even! I can beat him with a ol’ single shot!”

“I reckon,” Mr. Kent, the sheriff, said. “We’d just count the birds in the bag on Christmas Day.” The sheriff stroked the white grizzle on his chin, and it sounded like sandpaper. “That suit you, Kirk?”

He was mad then. His leg hurt, and he did not think about it.

“Sure,” he said, “I’ll match him, Christmas Day.” He did not have time to think about how hard it would be.

“He’s done offered you a bet, McKitridge,” Mr. Callicutt said. That was when he realized; from the stiff, hard way Mr. Callicutt said it, he knew it was a man’s bet.

After that, there was nothing he could do. Mr. Brannan offered to buy a pop all around on it, and everybody except Butternose went inside.

“I reckon you done pretty good, Kirk,” Mr. Callicutt said, when they got the drinks out.

“I’ll bet five on him,” Amos Beesinger said. “I’ll just take five of thatair little spunky.”

“You gonna have to find a McKitridge to take that bet, Amos,” the sheriff said. Then the sheriff laughed. “But that won’t be hard,” he said. “The woods is simply full of them things.”

Everybody laughed at that, and he tried to grin too. Then they were arranging for the sheriff to judge the match.

“And you better send Peters out to warden on the other side of town that day, in case they should chancet to go over the limit,” Mr. Brannan said.

“Shoot!” the sheriff said. “Peters is liable to hate missin’ it so much, he’ll re-sign the warden’s job just to come along!”

While they were laughing, he managed to slip out.

He did not tell even his father that day. His father looked at him strangely when he came in that night, but he did not want to tell anybody until he had it arranged. It took him two days to get up nerve to ask Mr. Callicutt about the .410. Standing in Mr. Callicutt’s store, he worked the pump, being very careful to do it all right.

“Tell you what,” Mr. Callicutt said finally. “That gun ain’t sold. I’ll give it to you wholesale price.”

He thought about that carefully for a while.

“Ten per cent off for cash, of course,” Mr. Callicutt said, not looking at him.

“I guess it’s still too much,” he said.

“Oh?” Mr. Callicutt said. They thought a minute. “You might get a job.”

“Yes, sir,” he said, “if there was one around.”

“Oh,” Mr. Callicutt said, “yes.”

“Yes, sir,” he said. “Well, thank you.” He turned, letting his hand run along the counter, starting for the door.

“Wait,” Mr. Callicutt said. “I been needin’ a boy, afternoons. I’d expect a lot. Can’t pay much.”

“Would it be enough?” he said. Mr. Callicutt got out the pad and pencil, and began figuring.

“You’d have a little left over for shells, you work all day Satiddys,” Mr. Callicutt said finally.

“Yes, sir,” he said, and tried to walk to the door.

When he got outside, he ran. He ran straight to the kitchen and found his mother and told her all at once; how Amos Beesinger was going to bet five, and about Mr. Callicutt, and his mother said no, at once. She began to look queer when he told her, and then she said no.

When his father came in from the farm, they talked about it.

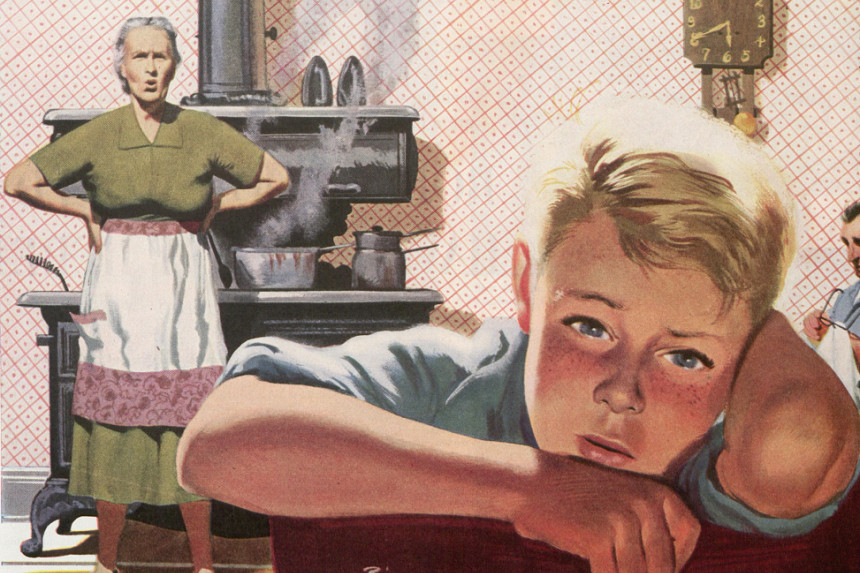

“I’m just not going to allow it,” his mother said. “No, sir.”

“Now, mama,” his father said.

His mother held her head very straight, and he could tell she was mad. Afterward, when she began to cry, he and his father went out and sat on the porch. His father puffed on his pipe for a long time.

“She’ll come around,” his father said finally.

But she did not come around. She would not budge an inch, so it did not surprise him, really, when his father winked at him the first morning, early in October, and motioned him outside right after breakfast.

“Tell her you’re going with me to the farm,” his father said.

When they were in the car, his father jerked his head toward the back seat. He looked at the gunny sacks on the floor, and he thought at first it was the .410, but when he unwrapped it, he saw it was his father’s big twelve gauge. His father grinned.

“She didn’t say anything about the twelve gauge,” his father said.

That first day he could remember very well. When they got to the dump, out toward the farm, his father began throwing tin cans up for him. At first he missed, and the gun seemed to kick a lot, but his father just kept sailing the cans out flat and hard.

“That’s the way they fly,” his father said. “ You don’t sight ‘em. Just swing with them, and when it feels right, pull. You’ll get so you know.” His father was sweating by that time, grunting when he threw.

By the end of that week, he was hitting a few of them, and the kick did not bother him anymore. They went to the dump whenever they could slip away; his father threw the cans and grunted, and he shot. In November Amos Beesinger began to go out with them, so they could put up two cans at once, and before long he was beginning to get both of them. They worked with the dogs, too, trimming them down until their rib cages showed all along the flank, training them, and he talked a good deal to Amos Beesinger and Mr. Brannan about woods shooting and covey flushes and the things you needed to know.

“He just shoots so natural-like, Mr. Frank,” Amos said one day as they rode back into town. “ It is a purty thing to watch.”

“Cans aren’t quail,” his father said. But Kirk was already feeling fairly sure about it. Amos, particularly, told him a lot; about opening the craw of the first bird, to see what they were eating, and about figuring the way the birds would turn before the flush.

“And quail ain’t dumb,” Amos told him one day. “Quail talk• They tell each other where they be going. About seventy-eighty foot out, ol’ outside birds turn back in toward the center and crost close, so they kin talk and get together again. You wait for ‘em, pull just then, you get both birds on one shot.” Amos looked at him carefully.

“My pappy use’ to do that to save shells.”

“Do they really talk, Amos?” he said.

“Sompen. Anyways, they crost close.”

“I’ll remember,” he said; “ just wait till the season opens.”

And he did try to remember everything they told him when the season opened a week later. He spent all his spare time hunting, staying out in the clear, crisp December afternoons until the sun went down. His mother did not suspect anything; she noticed that he came in tired and hungry, but she was used to his being out, and he was careful to be secret. Occasionally his father went with him, but usually he went alone, ranging out over the hills and bottoms and farms which he knew as well as anybody, because he had always traveled over them. One Saturday, Callicutt let him go, and he hunted all day, pausing at the tops of the hills to watch the dogs work the fields of sedge or lespedeza. He was getting doubles on the coveys then. The dogs were working beautifully, and he felt fine about it. That day he got the limit.

“O.K.,” his father said, grinning, “ we give ‘em hell.” Then his father thought a minute. “But it’s going to be tough.”

“Yes, sir,” he said, “I know it.”

Three days before Christmas the weather turned bad. He kept on hunting, staying out in the damp, sweetsmelling cold until his hands were red and raw in his pockets. Woods shooting still bothered him, but he worried more about the bet and about the McKitridge dog. Maybe that was why, on the day of the match;he was nervous and missed the first two shots.

The first one was a covey, and he thought he was on the birds. He shot twice, and nothing happened. By the time Bump pointed one of the singles from the covey, he was shaking pretty badly. He was very conscious of the line of quiet men behind him and of the fact it was a man’s bet, and he missed the bird clean.

He had been nervous about it all morning. He was up before light, and saw it dawn clear and windless. His mother heard him and was up, too, thinking he wanted to open the presents. When they sat around the little tree, after a quick breakfast, he had trouble even thinking about the presents. He could tell his mother knew something was wrong, because his father was quiet, too, even though he and his father had agreed the day before to make it as much like any Christmas as they could. And after the presents there was nothing to do but worry about it until ten o’clock. That part, at least, was easy; he always went with his father to hunt on Christmas Day.

By the time they got to Callicutt’s store, all the men were waiting. The sheriff and some of the townsmen, in the sheriff’s car. Mr. Brannan; Amos Beesinger, on a tired-looking mule. The McKitridges were there, too, in a mud-splashed pickup. Old Man McKitridge, his face as carved and expressionless as ever, and Butternose and three more of the McKitridge boys. One of the boys was hunkered down in the bed of the pickup with his arm over Blue Mike. Blue Mike just stood there, his big flat head up and alert, looking out balefully at the men, waiting. The way they were all waiting, watching him, scared Kirk. His hands were already shaking a little when they started out, sliding across the muddy hill roads in a long slow line. He turned back once and saw Amos slapping at the tired mule, and Amos waved to him, so he felt a little better. But when they got out at Markham’s farm, Markham and his son were waiting too. The men all piled out, quiet and not smiling.

He had trouble getting the shells into the big pump, but he thought he was all right when Pompey pointed the first covey. Then he missed, and by the time he took the shot at the single, his eyes were hot and sandy and he knew he was not on the bird.

The gun seemed to kick a lot on the single. He heard Butternose’s gun on the right, two shots, and then one, and Butternose’s raucous laugh. And all of a sudden he got mad.

It boiled up in him like getting sick at the stomach; he forgot the line of quiet men behind him, and his father and everything. He yelled at the dogs once and waved his arm hard in the direction he wanted to go, and then he began to walk fast. It was Pompey that pointed then. It was a beauty, and it helped a lot. The dog was quartering a sedge field, moving fast, and came to a log and jumped to it to go on over. But when Pompey’s feet hit the top of the log he recoiled suddenly and teetered there, balanced in the clear dead air, ears cocked and head turned down. Kirk could hear the quiet, admiring “Ah-h-h-h” of the men behind him. He got behind the dog quickly; when the birds came up this time, he was not shaking, he was sure, and the first bird collapsed. He took his time on the second shot and saw that one go down too.

“You good dog,” he said proudly, when Pompey brought the bird in. “You good ol’ dog.”

After that he was sure of the shooting. Although he hit the first, he missed the second shot on the next covey, but he did not mind because it was a turning shot into the trees. He got two singles that came from that covey too. Bump and Pompey were hot now; they were not so fast as Blue Mike, but they hunted intelligently and handled the birds well. He was aware of the long white streak that was Blue Mike, far out ahead; he heard Butternose shooting again, and then again, and a third time. But he was busy with his own dogs and the next covey. He got two from that one, and Bump hunted down a single after the covey shot. So it surprised him to hear the sheriff yell for a break and lunch. That meant one o’clock.

It was harder then, standing in the gathered circle of men, while Old Man McKitridge and Mr. Brannan laid out the birds, and the sheriff counted. He tried not to look at the birds, because he was worried again.

“Gentlemen,” the sheriff said, “ I make it Kirk eight, McKitridge eleven.” When the sheriff said “Eleven,” it kept echoing in his mind, Eleven, eleven, eleven-eleven-eleven. It was a lot of birds.

Old Man McKitridge squatted close to Butternose, chewing. “My boy got one bird the dogs ain’t found,” Old Man McKitridge said. His sky-blue eyes stared off into nothingness and his face never changed. No one said anything for a moment.

“I understand it is just birds in the bag,” the sheriff said. Tlie sheriff was watching Old Man McKitridge carefully.

“Shuah,” Old Man McKitridge said, “that’s right, shurf. I was just saying. My boy gonna get plenty more birds.”

“I just wanted it clear,” the sheriff said.

“That’s right,” Old Man McKitridge said, still squatting there, not looking at anything. “We ain’t worried. Why, that dog ain’t even run none yit. He ain’t tired.”

Kirk knew that was true too. Blue Mike sat at the edge of the circle, erect and still, and he did not look as if he had been running at all. Bump and Pompey were both stretched out, their tongues lolling. When he compared them with Blue Mike, he knew he could count on only one thing. Blue Mike was really Old Man McKitridge’s dog; his father thought that Butternose might begin to push the dog too hard and make him run over birds.

He threw away the sandwich he could not eat, when the men stood up again. A wind was blowing from the north now, and dark, spotty clouds had formed, so that they walked under a billowing shade which sometimes swept away, leaving the tawny fields reddened and smelling of earth again. It meant a storm; the birds would be hugging close to cover. They would be hard to find, and time was running out.

By two, the clouds were solid and the wind was strong. He did all he could to coax the dogs; he was pleased that they responded and began to work faster. He got a single, and then one more from a covey in a stand of pin oak where there was no time for a second shot. He heard Butternose shoot twice, and then, later, he could hear him cursing Blue Mike. That helped some; maybe what his father had said was happening now. Maybe Butternose was pushing Mike too fast.

“Forty-five minutes!” the sheriff yelled. “Kirk at ten, McKitridge at thirteen!” The sheriff yelled twice, once to each side. Three birds, he kept thinking, three birds, that means a covey and a single, and now there isn’t any time.

When Bump got the single, he could tell the bird was running. Bump stalked him nervously, trying to hold it, walking stiff-legged as though there were eggs under him. He began to run then; he glanced back once and saw Amos Beesinger right behind him. Amos’ thick body was leaning forward a little and his big, flat nose was up, as though he were sniffing. The bird flushed before he got to the dog. He had to throw the heavy gun up and shoot before it got to the trees, and for a moment he thought he had missed. Then he heard Amos’ little yip behind him, and he knew the bird was down.

After that he could not remember very well, because it went too fast. He heard Butternose cursing Blue Mike again, violently, and he heard someone yell “Fifteen minutes!” and he saw Pompey, far out ahead, running hard down a draw, covering ground between birdy spots. Then suddenly Pompey was flattened out to the ground, as though he had come to a full stop in midstride. He heard his own voice, yelling, too, then, because it was an absurd point; the dog’s head was twisted down and over his right shoulder, and his body was cramped up. The birds were right under him, and it seemed impossible to hold them. He could remember running hard, calling to the dog to hold, and Amos, close up behind him, running, too, calling to him in a strange, quivering voice.

“Ain’t no time, Kirk! Get the single and wait! Git ‘em when they crost close!”

He ran on, watching the crouched, hewn dog, thinking the covey was bound to break any time. But Pompey had them, and then he was coming in slowly, very calm and tired. The birds came up neatly, spread like a fan; he dropped the first one quickly and then he waited, consciously, for what seemed much too long, until the outside birds began to turn in, and he kept on waiting until they were a foot apart, and then he shot.

He never did see the birds go down. He just heard Amos’ wild and awful shout close behind him, and felt the big man grab him up and almost throw him down again; he could hear Amos laughing crazily and yelling; something about “I be pretty be-damn!” The men were all laughing and pounding him, but they stopped when Pompey came in the second time, bringing the last bird. The dog was worn down and came in slowly. Kirk forgot the men then, and dropped to his knees to hug the dog, crying now because he was not ashamed any more. From somewhere behind him the sheriff’s voice kept going.

“A triple!” the sheriff kept saying. “I am a foolish, fritterin’ idiot for shore!”

When the McKitridges came in, everyone got quiet. Butternose was talking loudly, saying something was wrong with it, asking about the time.

“Shut up,” Old Man McKitridge said. His voice was sharp and dignified. “You just been whupped fahr, that’s all. . . . Shurf, I owe you ten.” Old Man McKitridge walked slowly toward the sheriff, tugging for his wallet in the overalls breast pocket.

Then Old Man McKitridge stopped and turned and looked at him so hard he dropped his eyes. It was very quiet; from somewhere he could hear a peckerwood hammering.

“I send my compliments,” Old Man McKitridge said quietly. “Ain’t many men kin do that. My compliments.”

That evening, when he was sitting still in front of the open fire, feeling very tired, he wondered about it. His mother had looked so surprised when he and his father burst in from the car and told her. She had not said much; she just stood there, looking rather white, smiling at him strangely. She had been quiet, too, at supper. He did not know whether she was angry or not.

His father and mother came in then. “ I guess you’d better tell him, mama,” his father said. “ He’s earned it.”

His mother looked at the floor. When she spoke, she sounded serious. “ Mr. Callicutt brought you a present,” she said. “Two presents. They’re there on the mantel.” She pointed to a long brown package and an envelope that he had not noticed.

He opened the envelope first, because he knew just how the .410 looked and felt, so he did not need to unwrap that. In the envelope were twenty-six one-dollar bills, all new, and a note.

“Any man can do that deserves his pay and his gun both,” the penciled note said. It was signed “Callicutt.”

He grinned, and then stopped and looked at his mother, wondering. “I guess you can keep it,” she said, beginning to cry. “ It looks like you’re old enough to use it.”

Featured image: Bill Fleming (©SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now