A Post regular and writer of more than 100 short stories in the early twentieth century, Thomas Beer was best known for his biography of Stephen Crane as well as his novel The Mauve Decade. Beer’s fiction contained evocative metaphors and complex characters that preceded work along the same vein from writers like William Faulkner. In “Mummery,” Beer’s O. Henry Prize finalist story from 1921, Myrtle Egg is excitedly awaiting her son’s return from the Navy when a stranger arrives claiming to be her long-lost father.

Published on July 30, 1921

On Monday, Mrs. Egg put her husband on the eastbound express with many orders. He was not to annoy Adam by kissing him when they met, if they met in public. He was to let Adam alone in the choice of civil dress, if Adam wanted to change his naval costume in New York. He was not to get lost in Brooklyn, as he had done before. He was to visit the largest moving picture theaters and report the best films on his return. She made sure that Egg had her written list of lesser commands safe in his wallet, then folded him to her bosom, sniffled, and patted him up the steps of the coach.

A red-haired youth leaned through an open window and inquired, “Say, lady, would you mind tellin’ me just what you weigh?”

“I ain’t been on the scales in years, bub,” said Mrs. Egg equably; “not since about when you was born. Does your mamma ever wash out your mouth with soap?”

An immediate chorus of laughter broke from the platform loungers. The train jerked forward. The youth pulled in his head. Mrs. Egg stood puffing triumphantly with her hands on her hips.

“It’s a shame,” the baggage master told her, “that a lady can’t be kind of — kind of — ”

“Fat,” said Mrs. Egg; “and bein’ tall makes it worse. All the Packers ’ve always been tall. When we get fat we’re holy shows. But if that kid’s mother’d done her duty by him he’d keep his mouth shut.”

The dean of the loungers put in, “Your papa was always skinny, Myrtle.”

“I can’t remember him much,” Mrs. Egg panted, “but he looks skinny in his pictures. Well, I got to get home. There’s a gentleman coming over from Ashland to look at a bull.”

She trod the platform toward the motor at the hitching rails, and several loungers came along gallantly. Mrs. Egg cordially thanked them as she sank into the driving seat, settled her black straw hat and drove off.

Beholding two of her married daughters on the steps of the drug store, she stopped the car and shouted: “Hey, girls, the fleet’s gettin’ in tomorrow. Your papa’s gone to meet Dammy. I just shoved him on the train. By gee! I forgot to tell him he was to fetch home — no, I wrote that down — well, you come out to supper Wednesday night.”

“But can Dammy get discharged all in one day?” a daughter asked.

Mrs. Egg had no patience with such imbecility. She snapped, “Did you think they’d discharge him a foot at a time, Susie?” and drove on up the street, where horse chestnuts were ready to bloom, appropriately, since Adam was fond of the blossoms. She stopped the car five times to tell boys that Adam would be discharged tomorrow, and made a sixth stop at the candy shop, where a clerk brought out a chocolate ice cream with walnut sauce. He did this mechanically. Mrs. Egg beamed at him, although the fellow was a newcomer and didn’t know Adam.”

“My boy’ll be home Wednesday,” she said, giving the dish back.

“Been in the Navy three-four years, ain’t he?”

Mrs. Egg sighed. “April 14, 1917. He was twenty-one las’ week, so he gets discharged soon as the fleet hits New York. My gee, think of Dammy being twenty-one!”

She drove on, marveling at time, and made her seventh stop at the moving-picture theater. The posters of the new feature film looked dull. The heavily typed list of the current-events weekly took her sharp eye. She read, “Rome Celebrates Anniversary — Fleet Sails from Guantanamo,” and chuckled. She must drive in to see the picture of the fleet. She hadn’t time to stop now, as lunch would be ready. Anyhow, night was the time for movies. She drove on and the brick business buildings gave out into a dribble of small frame cottages, mostly shabby. Edith Webb was coming out of her father’s gate.

Mrs. Egg made an eighth halt and yelled, “Hey, Edie, Dammy’ll be home Wednesday night,” for the pleasure of seeing the pretty girl flush. Adam had taken Edith to several dances at Christmas. Mrs. Egg chuckled as the favored virgin went red, fingering the top of the gatepost. Edith would do. In fact, Edith was suitable, entirely.

“Well, I’m glad,” the girl said. “Oh, say, was it our house or the next one you used to live in? Papa was wondering last night.”

“It was yours,” Mrs. Egg declared; “and thank your stars you’ve got a better father than I had, Edie. Yes, right here’s where I lived when I was your age and helped mamma do sewin’, and sometimes didn’t get enough to eat. I wonder if that’s why — well, anyhow, it’s a solid-built house. I expect Dammy’ll call you up Wednesday night.” She chuckled immensely and drove on again.

His cows were grazing in the pastures. His apple trees were looking well. The red paint of his monstrous water tanks soothed her by their brilliance. A farmhand helped her out of the car and she took the shallow veranda steps one at a time, a little moody, wishing that her mother was still alive to see Adam’s glory. However, there were six photographs of Adam about the green sitting room in various uniforms, and these cheered her moment of sorrow. They weren’t altogether satisfactory. His hard size didn’t show in single poses. He looked merely beautiful. Mrs. Egg sniffled happily, patting the view of Adam in white duck. The enlarged snapshot portrayed him sitting astride a turret gun. It was the best of the lot, although he looked taller in wrestling tights, but that picture worried her. She had always been afraid that he might kill someone in a wrestling match. She took the white-duck photograph to lunch and propped it against the pitcher of iced milk.

“It’ll be awful gettin’ him clothes,” she told the cook; “except shoes. Thank God, his feet ain’t as big as the rest of him! Say, remind me to make a coconut cake in the morning in the big pan. He likes ’em better when they’re two or three days old so the icin’s kind of spread into the cake. I’d of sent a cake on with his papa, but Mr. Egg always drops things so much. It does seem — ” The doorbell rang. Mrs. Egg wiped her mouth and complained, “Prob’ly that gentleman from Ashland to look at that bull calf. It does seem a shame folks drop in at mealtimes. Well, go let him in, Sadie.”

The cook went out through the sitting room and down the hall. Mrs. Egg patted her black hair, sighed at her third chop and got up. The cook’s voice mingled with a drawling man’s tone. Mrs. Egg drank some milk and waited an announcement. The cook came back into the dining room and Mrs. Egg set down the milk glass swiftly, saying, “Why, Sadie!”

“He — he says he’s your father, Mis’ Egg.”

After a moment Mrs. Egg said, “Stuff and rubbidge! My father ain’t been seen since 1882. What’s the fool look like?”

“Awful tall — kinda skinny — bald — ”

A tremor went down Mrs. Egg’s back. She walked through the sitting room and into the sunny hall. The front door was open. Against the apple boughs appeared a black length, topped by a gleam. The sun sparkled on the old man’s baldness. A shivering memory recalled that her father’s hair had been thin. His dark face slid into a mass of twisting furrows as Mrs. Egg approached him.

He whispered, “I asked for Myrtle Packer down round the station. An old feller said she was married to John Egg. You ain’t Myrtle?”

“I’m her,” said Mrs. Egg. Terrible cold invaded her bulk. She laced her fingers across her breast and gazed at the twisting face.

The whisper continued: “They tell me your mamma’s in the cem’tery, Myrtle. I’ve come home to lay alongside of her. I’m grain for the grim reaper’s sickle. In death we shan’t be divided; and I’ve walked half the way from Texas. Don’t expect you’d want to kiss me. You look awful like her, Myrtle.”

Tears rolled out of his eyes down his hollowed cheeks, which seemed almost black between the high bones. His pointed chin quivered. He made a wavering gesture of both hands and sat down on the floor. Behind Mrs. Egg the cook sobbed aloud. A farmhand stood on the grass by the outer steps, looking in. Mrs. Egg shivered. The old man was sobbing gently. His head oscillated and its polish repelled her. He had abandoned her mother in 1882. “Mamma died, back in 1910,” she said. “I dunno well — ”

The sobbing was thin and weak, like an ailing baby’s murmur. It pounded her breast.

She stared at the ancient dusty suitcase on the porch and said, “Come up from Texas, have you?”

“There’s no jobs lef’ for a man seventy-six years of age, Myrtle, except dyin’. I run a saloon in San Antonio by the Plaza. Walked from Greenville, Mississippi, to Little Rock. An old lady give me carfare, there, when I told her I was goin’ home to my wife that I’d treated so bad. There’s plenty Christians in Arkansaw. And they’ve pulled down the old Presbyterian church your mamma and I was married in.”

“Yes; last year. Sadie, take Mr. Packer’s bag up to the spare room. Stop cryin’, papa.”

She spoke against her will. She could not let him sit on the floor sobbing any longer. His gleaming head afflicted her. She had a queer emotion. This seemed most unreal. The gray hall wavered like a flashing view in a film.

“The barn’d be a fitter place for me, daughter. I’ve been a — ”

“That’s all right, papa. You better go up and lie down, and Sadie’ll fetch you up some lunch.”

His hand was warm and lax. Mrs. Egg fumbled with it for a moment and let it fall. He passed up the stairs, drooping his head. Mrs. Egg heard the cook’s sympathy explode above, and leaned on the wall and thought of Adam, coming home Wednesday night. She had told him a thousand times that he mustn’t gamble or mistreat women or chew tobacco “like your Grandfather Packer did.” And here was Grandfather Packer, ready to welcome Adam home!

The farmhand strolled off, outside, taking the seed of this news. It would be in town directly.

“Oh, Dammy,” she said, “and I wanted everything nice for you!”

In the still hall her one sob sounded like a shout. Mrs. Egg marched back to the dining room and drank a full glass of milk to calm herself.

“Says he can’t eat nothin’, Mis’ Egg,” the cook reported, “but he’d like a cup of tea. It’s real pitiful. He’s sayin’ the Twenty-third Psalm to himself. Wasted to a shadder. Asked if Mr. Egg was as Christian an’ forbearin’ as you. Mebbe he could eat some buttered toast.”

“Try and see, Sadie; and don’t bother me. I got to think.”

She thought steadily, eating cold rice with cream and apple jelly. Her memory of Packer was slim. He had spanked her for spilling ink on his diary. He had been a carpenter. His brothers were all dead. He had run off with a handsome Swedish servant girl in 1882, leaving her mother to sew for a living. What would the county say? Mrs. Egg writhed and recoiled from duty. Perhaps she would get used to the glittering bald head and the thin voice. It was all most unreal. Her mother had so seldom talked of the runaway that Mrs. Egg had forgotten him as possibly alive. And here he was! What did one do with a prodigal father? With a jolt she remembered that there would be roast veal for supper.

At four, while she was showing the Ashland dairyman the bull calf, child of Red Rover VII and Buttercup IV, Mrs. Egg saw her oldest daughter’s motor sliding across the lane from the turnpike. It held all three of her female offspring. Mrs. Egg groaned, drawling commonplaces to her visitor, but he stayed a full hour, admiring the new milk shed and the cider press. When she waved him goodbye from the veranda she found her daughters in a stalwart group by the sitting room fireplace, pink-eyed and comfortably emotional. They wanted to kiss her. Mrs. Egg dropped into her particular mission chair and grunted, batting off embraces.

“I suppose it’s all over town? It’d travel fast. Well, what d’you think of your grandpapa, girls?”

“Don’t talk so loud, mamma,” one daughter urged. Another said, “He’s so tired he went off asleep while he was telling us how he nearly got hung for shooting a man in San Antonio.”

Mrs. Egg reached for the glass urn full of chocolate wafers on the table and put one in her mouth. She remarked, “I can see you’ve been havin’ a swell time, girls. A sinner that repenteth — ”

“Why, mamma!”

“Listen,” said Mrs. Egg; “if there’s going to be any forgiving done around here, it’s me that’ll do it. You girls was raised with all the comforts of home and then some. You never he’ped anybody do plain sewin’ at fifteen cents a hour nor had to borrow money to get a decent dress to be married in. This thing of hearin’ how he shot folks and kept a saloon in Texas is good as a movie to you. It don’t set so easy on me. I’m old and tough. And I’ll thank you to keep your mouths shut. Here’s Dammy comin’ home Wednesday out of the Navy, and all this piled up on me. I don’t want every lazyjake in the county pilin’ in here to hear what a bad man he’s been, and dirty the carpets up. Dammy likes things clean. I’m a better Christian than a lot of folks I can think of, but this looks to me like a good deal of a bread-and-butter repentance. Been devourin’ his substance in Texas and come home to — ”

“Oh, mamma, your own papa!”

“That’s as may be. My own mamma busted her eyesight and got heart trouble for fifteen mortal years until your papa married me and gave her a home for her old age, and never a whimper out of her, neither. She’s where she can’t tell me what she thinks of him and I dunno what to think. But I’ll do my own thinkin’ until Dammy and your papa gets back and tell me what they think. This is your papa’s place — and Dammy’s. It ain’t a boardin’ house for —— ”

“Oh, mamma!”

“And it’s time for my nap.”

Susan, the oldest daughter, made a tremulous protest. “He’s seventy-six years old, mamma, and whatever he’s done —— ”

“For a young woman that talked pretty loud of leavin’ her husband when he came home kind of lit up from a club meetin’ — ” Mrs. Egg broke in. Susan collapsed and drew her gloves on hastily. Mrs. Egg ate another chocolate wafer and resumed: “This here’s my business — and your papa’s and Dammy’s. I’ve got it in my head that that movie weekly picture they had of Buttercup Four with her price wrote out must have been shown in San Antonio. And you’ll recollect that your papa and me stood alongside her while that fresh cameraman took the picture. If I was needin’ a meal and saw I’d got a well-off son-in-law —— ”

“Mamma,” said Susan, “you’re perfectly cynical.” Mrs. Egg pronounced, “I’m forty-five years of age,” and got up.

The daughters withdrew. Mrs. Egg covered the chocolate urn with a click and went into the kitchen. Two elderly farmhands went out of the porch door as she entered.

Mrs. Egg told the cook: “Least said, soon’st mended, Sadie. Give me the new cream. I guess I might’s well make some spice cookies. Be pretty busy Wednesday. Dammy likes ‘em a little stale.”

“Mis’ Egg,” said the cook, “if this was Dammy that’d kind of strayed off and come home sick in his old age — ”

“Give me the cream,” Mrs. Egg commanded, and was surprised by the fierceness of her own voice. “I don’t need any help seein’ my duty, thanks!”

At six o’clock her duty became highly involved. A friend telephoned from town that the current-events weekly at the moving-picture theater showed Adam in the view of the dreadnoughts at Guantanamo.”

“Get out,” said Adam’s mother. “You’re jokin’! . . . Honest? Well, it’s about time! What’s he doin’? . . . Wrestlin’? My! Say, call up the theater and tell Mr. Rubenstein to save me a box for the evenin’ show.”

“I hear your father’s come home,” the friend insinuated.

“Yes,” Mrs. Egg drawled, “and ain’t feelin’ well and don’t need comp’ny. Be obliged if you’d tell folks that. He’s kind of sickly. So they’ve got Dammy in a picture. It’s about time!” The tremor ran down her back. She said “Good night, dearie,” and rang off.

The old man was standing in the hall doorway, his head a vermilion ball in the crossed light of the red sunset.

“Feel better, papa?”

“As good as I’m likely to feel in this world again. You look real like your mother settin’ there, Myrtle.” The whisper seemed likely to ripen as a sob.

Mrs. Egg answered, “Mamma had yellow hair and never weighed more’n a hundred and fifty pounds to the day of her death. What’d you like for supper?”

He walked slowly along the room, his knees sagging, twitching from end to end. She had forgotten how tall he was. His face constantly wrinkled. It was hard to see his eyes under their long lashes. Mrs. Egg felt the pity of all this in a cold way.

She said, when he paused: “That’s Adam, there, on the mantelpiece, papa. Six feet four and a half he is. It don’t show in a picture.”

“The Navy’s a rough kind of life, Myrtle. I hope he ain’t picked up bad habits. The world’s full of pitfalls.”

“Sure,” said Mrs. Egg, shearing the whisper. “Only Dammy ain’t got any sense about cards. I tried to teach him pinochle, but he never could remember none of it, and the hired men always clean him out shakin’ dice. He can’t even beat his papa at checkers. And that’s an awful thing to say of a bright boy!”

The old man stared at the photograph and his forehead smoothed for a breath. Then he sighed and drooped his chin.

“If I’d stayed by right principles when I was young — ”

“D’you still keep a diary, papa?”

“I did used to keep a diary, didn’t I? I’d forgotten that. When you come to my age, Myrtle, you’ll find yourself forgettin’ easy. If I could remember any good things I ever did — ”

The tears dripped from his jaw to the limp breast of his coat. Mrs. Egg felt that he must be horrible, naked, like a doll carved of coconut bark Adam had sent home from Havana. He was darker than Adam even. In the twilight the hollows of his face were sheer black. The room was gray. Mrs. Egg wished that the film would hurry and show something brightly lit.

The tears dripped from his jaw to the limp breast of his coat. Mrs. Egg felt that he must be horrible, naked, like a doll carved of coconut bark Adam had sent home from Havana. He was darker than Adam even. In the twilight the hollows of his face were sheer black. The room was gray. Mrs. Egg wished that the film would hurry and show something brightly lit.

The dreary whisper mourned, “Grain for the grim reaper’s sickle, that’s what I am. Tares mostly. When I’m gone you lay me alongside your mamma and — ”

“Supper’s ready, Mis’ Egg,” said the cook.

Supper was odious. He sat crumbling bits of toast into a bowl of hot milk and whispering feeble questions about dead folk or the business of the vast dairy farm. The girls had been too kind, he said.

“I couldn’t help but feel that if they knew all about me — ”

“They’re nice sociable girls,” Mrs. Egg panted, dizzy with dislike of her veal. She went on: “And they like a good cry, never havin’ had nothin’ to cry for.”

His eyes opened wide in the lamplight, gray brilliance sparkled. Mrs. Egg stiffened in her chair, meeting the look.

He wailed, “I gave you plenty to cry for, daughter.” The tears hurt her, of course.

“There’s a picture of Dammy in the movies,” she gasped. “I’m goin’ in to see it. You better come. It’ll cheer you up, papa.”

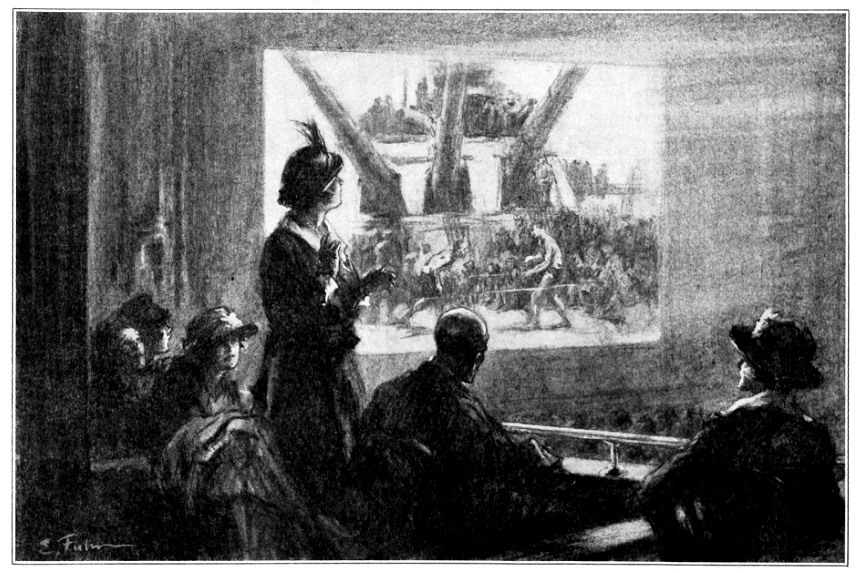

She wanted to recall the offer too late. In the car she felt chilly. He sank into a corner of the tonneau like a thrown laprobe. Mrs. Egg talked loudly about Adam all the way to town and shouted directions to the driving farmhand in order that the whisper might not start. The manager of the theater had saved a box for her and came to usher her to its discomfort. But all her usual pleasure was gone. She nodded miserably over the silver-gilt rail at friends. She knew that people were craning from far seats. Her bulk and her shadow effaced the man beside her. He seemed to cower a little. At eight the show began and Mrs. Egg felt darkness as a blessing, although the shimmer from the screen ran like phosphorus over the bald head, and a flash of white between two parts of the advertisement showed the dark wrinkles of his brow.

“Like the pictures, papa?”

“I don’t see well enough to take much pleasure in ’em, Myrtle.”

A whirling globe announced the beginning of the weekly. Mrs. Egg forgot her burdens. She was going to see Adam. She took a peppermint from the bag in her hand and set her teeth in its softness, applauded a view of the President and the arrival of an ambassador in New York. Then the greenish letters declared “The fleet leaves Guantanamo training ground,” and her eyes hurt with staring. The familiar lines of anchored battleships appeared with a motion of men in white on the gray decks. The screen showed a race of boats which melted without warning to a mass of white uniforms packed about the raised square of a roped-in platform below guns and a turret clouded with men. Two tanned giants in wrestling tights scrambled under the ropes. There was a flutter of caps.

“Oh!” said Mrs. Egg. “Oh!”

She stood up. The view enlarged. Adam was plain as possible. He grinned, too; straight from the screen at her. The audience murmured. Applause broke out. Adam jerked his black head to his opponent — and the view flicked off into some stupid business of admirals. Mrs. Egg sat down and sobbed.

“Was that Adam, daughter? The — the big feller with black hair?”

“Yes,” said Mrs. Egg; “yes.” She was hot with rage against the makers of pictures who’d taken him from her. It was a shame. She crammed four peppermints into her mouth and groaned, about them, “As if people wouldn’t rather look at some good wrestlin’ than a lot of captains and stuff!”

“How long’s the boy been in the Navy, Myrtle?”

“April 14, 1917.”

The whisper restored her. Mrs. Egg yawned for an hour of nonsense about a millionaire and his wife who was far too thin. Her father did not speak, although he moved now and then. The show concluded. Mrs. Egg lumbered wearily out to her car in the dull street and vaguely listened to the whisper of old age. She couldn’t pay attention. She was going home to write the film company at length. This abuse of Adam was intolerable. She told the driver so. The driver agreed.

He reported, “I was settin’ next to Miss Webb.”

“That’s Dammy’s girl, papa. Go on, Sam. What did Edie say?”

“Well,” said the driver, “she liked seein’ the kid. She cried anyhow.”

Mrs. Egg was charmed by the girl’s good sense. The moon looked like a quartered orange over the orchard.

She sighed, “Well, he’ll be home Wednesday night, anyhow. Edie ain’t old enough to get married yet. Hey, what’s the house all lit up for? Sadie ought to know better.”

She prepared a lecture for the cook. The motor shot up the drive into a babble and halted at the steps. Someone immense rose from a chair and leaped down the space in one stride.

Adam said, “H’lo, mamma,” and opened the car door.

Mrs. Egg squealed. The giant lifted her out of her seat and carried her into the sitting room. The amazing muscles rose in the flat of his back. She thought his overshirt ripped. The room spun. Adam fanned her with his cap and grinned.

“Worst of radiograms,” he observed; “the boys say papa went on to meet me. Well, it’ll give him a trip. Quit cryin’, mamma.”

“Oh, Dammy, and there ain’t nothin’ fit to eat in the house!”

Adam grinned again. The farm hands dispersed at his nod. Mrs. Egg beat down her sobs with both hands and decried the radio service that could turn Sunday into Tuesday. Here was Adam, though, silently grinning, his hands available, willing to eat anything she had in the pantry. Mrs. Egg crowed her rapture in a dozen bursts.

The whispering voice crept into a pause with, “You’ll be wantin’ to talk to your boy, daughter. I’ll go to bed; I guess.”

“Dammy,” said Mrs. Egg, “this is — ”

Adam stopped rolling a cigarette and nodded to the shadow by the hall door. He said, “How you? The boys told me you’d got here,” and licked the cigarette shut with a flash of his red tongue. He struck a match on the blue coating of one lean thigh and lit the cigarette, then stared at the shadow. Mrs. Egg hated the old man against reason as the tears slid down the dark face.

“Grain for the grim reaper’s sickle, daughter. You’ll be wantin’ to talk to your boy. I guess I’ll say good night.” He faded into the hall.

“Well, come, let’s see what there is to eat, mamma,” said Adam, and pulled Mrs. Egg from her chair.

He sat on the low ice chest in the pantry and ate chocolate cake. Mrs. Egg uncorked pear cider and reached, panting, among apple-jelly glasses. Adam seldom spoke. She didn’t expect talk from him. He was sufficient. He nodded and ate. The tanned surface of his throat dimpled when he swallowed things. His small nose wrinkled when he chewed. Mrs. Egg chattered confusedly. Adam grinned when she patted his smooth hair and once said “Get out!” when she paused between two kisses to assure him he was handsome. He had his father’s doubts on the point perhaps. He was not, she admitted, exactly beautiful. He was Adam, perfect and hard as an oak trunk under his blue clothes. He finished the chocolate cake and began to eat bread and apple jelly.

He ate six slices and drank a mug of pear cider, then crossed his legs and drawled, “Was a fellow on the Nevada they called Frisco Cooley.”

“What about him, Dammy?”

“Nothin’. He was as tall as me. Skinny, though. Used to imitate actors in shows. Got discharged in 1919.”

“Was he a nice boy, Dammy?”

“No,” said Adam, and reached for the pear-cider bottle. He fell into his usual calm and drank another mug of cider. Mrs. Egg talked of Edie Webb. Adam grinned and kept his black eyes on the pantry ceiling. The clock struck eleven. He said, “They called him Frisco Cooley ’cause he came from San Francisco. He could wrinkle his face up like a monkey. He worked in a gamblin’ joint in San Francisco. That’s him.” Adam jerked a thumb at the ceiling.

“Dammy!”

“That’s him,” said Adam. “It took me a time to think of him, but that’s him.”

Mrs. Egg fell back against the ice chest and squeaked, “You mean you know this — ”

“Hush up, mamma!”

“But he walked part the way from San Antonio. He — ”

“He ain’t your father,” said Adam, “so don’t cry. Is there any maple sugar? The grub on the train was fierce.”

Mrs. Egg brought him the tin case of maple sugar. Adam selected a chunk of the brown stuff and bit a lobe of it. He was silent. Mrs. Egg marveled at him. His sisters had hinted that he wasn’t clever. She stood in awe, although her legs ached. Adam finished the lump of maple sugar and rose. He leaned on the shelves with his narrow waist curved against them and studied a row of quince-preserve jars. His nose wrinkled.

He asked, “You been fumigatin’?”

“Fumigatin’! Why, Dammy, there ain’t been a disease in the house since you had whoopin’ cough.”

“Sulphur,” Adam drawled.

“Why, Dammy Egg! I never used Sulphur for nothin’ in my life!”

He took a jar of preserves and ripped off the paraffin wafer that covered the top. Then he set the jar aside and sat down on the floor. Mrs. Egg watched him unlace his shoes.

He commanded, “You sit still, mamma. Be back in a minute.”

“Dammy, don’t you go near that heathen!”

“I ain’t.”

He swung across the kitchen floor in two strides and bumped his head on the top of the door. Mrs. Egg winced, but all her body seemed to move after the boy. Shiverings tossed her. She lifted her skirts and stepped after him. The veranda was empty. Adam had vanished, although the moon covered the dooryard with silver. The woman stared and shook. Then something slid down the nearest pillar and dropped like a black column to the grass. Adam came up the steps and shoved Mrs. Egg back to the pantry.

He spread some quince preserve on a slab of bread and stated, “He’s sittin’ up readin’ a lot of old copybooks, kind of. Got oil all over his head. It’s hair remover. Sulphur in it.”

“How could you ever smell that far, Dammy?”

“I wonder what’s in those books?” Adam pondered. He sat cross-legged on the ice chest and ate slowly for a time, then remarked, “You didn’t put up these quinces, mamma.”

“No; they’re Sadie’s. Think of your noticin’!”

“You got to teach Edie cookin’,” he said. “She can’t cook fit for a Cuban. Lots of time, though. Now, mamma, we can’t let this goof stay here all night. I guess he’s a thief. I ain’t goin’ to let the folks have a laugh on you. Didn’t your father always keep a diary?”

“Think of your rememberin’ that, Dammy! Yes, always.”

“That’s what Frisco’s readin’ up in. He’s smart. Used to do im’tations of actors and cry like a hose pipe. Spotted that. Where’s the strawb’ry jam?”

“Right here, Dammy. Dammy, suppose he killed papa somewheres off and stole his diaries!”

“Well,” said Adam, beginning strawberry jam, “I thought of that. Mebbe he did. I’d better find out. Y’oughtn’t to kill folks even if they’re no good for nothin’.”

“I’ll go down to the barn and wake some of the boys up,” Mrs. Egg hissed.

“You won’t neither, mamma. This’d be a joke on you. I ain’t goin’ to have folks sayin’ you took this guy for your father. Fewer knows it, the better. This is awful good jam.” He grinned and pulled Mrs. Egg down beside him on the chest. She forgot to be frightened, watching the marvel eat. She must get larger jars for jam. He reflected: “You always get enough to eat on a boat, but it ain’t satisfyin’. Frisco prob’ly uses walnut juice to paint his face with. It don’t wash off. Don’t talkin’ make a person thirsty?”

“Wait till I get you some more cider, Dammy.”

Adam thoughtfully drank more pear cider and made a cigarette. Wonderful ideas must be moving behind the blank brown of his forehead. His mother adored him and planned a recital of his acts to Egg, who had accused Adam of being slow-witted.

She wanted to justify herself, and muttered: “I just felt he wasn’t papa, all along. He was like one of those awful sorrowful persons in a movie.”

“Sure,” said Adam, patting her arm. “I wish Edie’d got as nice a complexion as you, mamma.”

“Mercy, Dammy!” his mother tittered and blushed.

Adam finished a third mug of cider and got up to examine the shelves. He scratched the rear of one calf with the other toe, and muscles cavorted in both legs as he reached for a jar of grapefruit marmalade. He peered through this at the lamp and put the jar back. Mrs. Egg felt hurt.

The paragon explained: “Too sour after strawb’ry, mamma. I’d like some for breakfast though. Back in a minute.”

He trotted out through the kitchen and vanished on the veranda. She shivered, being alone.

Adam came back and nodded: “Light’s out. Any key to that room?”

“No.”

“I can always think better when I’m eatin’,” he confessed, and lifted down the plate of spiced cookies, rejected them as too fresh, and pounced on a covered dish of apple sauce. This he absorbed in stillness, wriggling his toes on the oilcloth. Mrs. Egg felt entirely comfortable and real. She could hear the cook snoring. Behind her the curtain of the pantry window fluttered. The cool breeze was pleasant on her neck. Adam licked the spoon and said, “Back in a minute mamma,” as he started for the veranda door.

Mrs. Egg reposed on the ice chest, thinking about Adam. He was like Egg, in that nothing fattened him. She puzzled over tomorrow’s lunch. Baked ham and sweet potatoes, sugared; creamed asparagus; hot corn muffins. Dessert perplexed her. Were there any brandied peaches left? She feared not. They belonged on the upper shelf nearest the ice chest. Anxiety chewed her. Mrs. Egg climbed the lid by the aid of the window sill and reached up an arm to the shelf.

Adam said, “Here y’are, mamma.”

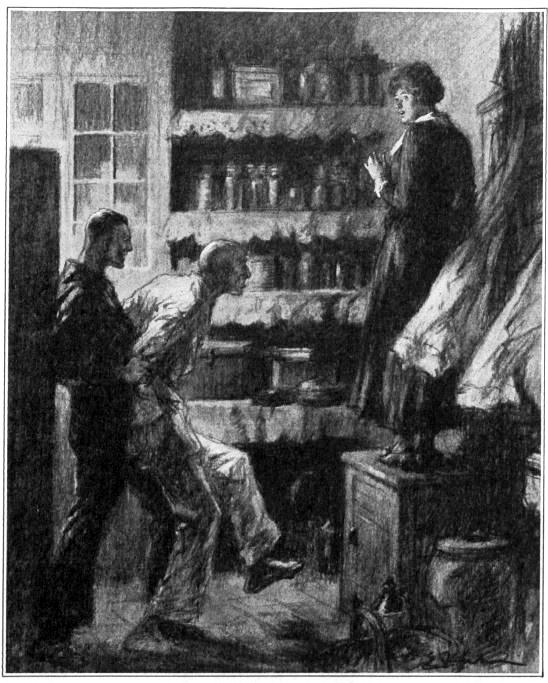

The pantry door shut. Mrs. Egg swung about. Adam stood behind a shape in blue pajamas, a hand locked on either of its elbows. He grinned at Mrs. Egg over the mummer’s shoulder. As the woman panted Sulphur entered her throat. The lamp threw a glare into the dark face, which seemed paler.

“Go on, Frisco,” said Adam, about the skull, “tell mamma about her father.”

A sharp voice answered, “Let go my arms. You’re killin’ me!”

“Quit kiddin’,” Adam growled. “Go on!”

“He ran a joint in San Francisco and gave me a job after I got out the Navy. Died last fall. I kind of nursed him. Told me to burn all these books — diaries. I read ’em. He called himself Peterson. Left all his money to a woman. She shut the joint. I looked some like him so I took a chance. Leggo my arms, Egg!”

“He’d ought to go to jail, Dammy,” said Mrs. Egg. “It’s just awful! I bet the police are lookin’ for him right now.”

“Mamma, if we put him in jail this’ll be all over the county and you’ll never hear the end of it.”

She stared at the ape with loathing. There was a star tattooed on one of his naked insteps. He looked no longer frail, but wiry and snakelike. The pallor behind his dark tan showed the triangles of black stain in his cheeks and eye sockets.

“He’s too smart to leave loose, Dammy.”

“It’ll be an awful joke on you, mamma.”

“I can’t help it, Dammy. He — ”

The prisoned figure toppled back against Adam’s breast and the mouth opened hideously. The lean legs bent.

“You squeezed him too tight, Dammy. He’s fainted. Lay him down.”

Adam let the figure slide to the floor. It rose in a whirl of blue linen. Mrs. Egg rocked on the chest.

The man thrust something at Adam’s middle and said in a rasp, “Get your arms up!”

Adam’s face turned purple beyond the gleaming skull. His hands rose a little and his fingers crisped. He drawled, “Fact. I ought have looked under your duds, you — ”

“Stick ‘em up!” said the man.

Mrs. Egg saw Adam’s arms tremble. His lower lip drew down. He wasn’t going to put his arms up. The man would kill him. She could not breathe. She fell forward from the ice chest and knew nothing.

She roused with a sense of great cold and was sitting against the shelves. Adam stopped rubbing her face with a lump of ice and grinned at her.

He cried, “By gee, you did that quick, mamma! Knocked the wind clear out of him.”

“Where is he, Dammy?”

“Dunno. Took his gun and let him get dressed. He’s gone, Say, that was slick!” Mrs. Egg blushed and asked for a drink. Adam dropped the ice into a mug of pear cider and squatted beside her with a shabby notebook.

“Here’s somethin’ for October 10, 1919.” He read: “Talked to a man from Ilium today in Palace Bar. Myrtle married to John Egg. Four children. Egg worth a wad. Dairy and cider business. Going to build new Presbyterian church.’ That’s it, mamma. He doped it all out from the diary.”

“The dirty dog!” said Mrs. Egg. She ached terribly and put her head on Adam’s shoulder.

“I’ll put all the diaries up in the attic. Kind of good readin’. Say, it’s after two. You better go to bed.”

In her dreams Mrs. Egg beheld a bronze menacing skeleton beside her pillow. It whispered and rattled. She woke, gulping, in bright sunlight, and the rattle changed to the noise of a motor halting on the drive. She gave yesterday a fleet review, rubbing her blackened elbows, but felt charitable toward Frisco Cooley by connotation; she had once sat down on a collie pup. But her bedroom clock struck ten times. Mrs. Egg groaned and rolled out of bed, reaching for a wrapper. What had the cook given Adam for breakfast? She charged along the upper hall into a smell of coffee, and heard Adam speaking below. His sisters made some feeble united interjection.

The hero said sharply: “Of course he was a fake! Mamma knew he was, all along, but she didn’t want to let on she did in front of folks. That ain’t dignified. She just flattened him out and he went away quiet. You girls always talk like mamma hadn’t as much sense as you. She’s kind of used up this morning. Wait till I give her her breakfast and I’ll come talk to you.”

A tray jingled.

Mrs. Egg retreated into her bedroom, awed. Adam carried in her breakfast and shut the door with a foot.

He complained: “Went in to breakfast at Edie’s. Of course she’s only sixteen, but I could make better biscuits myself. Lay down, mamma.”

He began to butter slices of toast, in silence, expertly. Mrs. Egg drank her coffee in rapture that rose toward ecstasy as Adam made himself a sandwich of toast and marmalade and sat down at her feet to consume it.

Illustrations by Ernest Fuhr (©SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now