Rights can be precarious things. In the political present, states pass laws that conflict with Supreme Court decisions, and issues of individual rights come into question at traffic stops and borders. Remarkably, rights were even less certain in the 1960s. That’s one reason that we stop to remember that President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Acts into law 55 years ago today. Despite this being a monumental piece of legislation, people are often confused about what it means and what protections it affords. The Act impacts everything from voting to schools to where court cases are heard and beyond. Let’s take a look at some of the most important pieces of the act, as well as the updates made in 1968 and 1991.

President Kennedy’s 1963 Civil Right Address (Uploaded to YouTube by JFK Library)

President John Kennedy had proposed the act in 1963, and Representative Emanuel Celler of New York introduced it, but a filibuster in the Senate ground its passage to a halt. After Kennedy was assassinated, Johnson made it a priority to drive the bill forward, and signed it upon its passage on July 2, 1964. The broad idea of the 1964 Act is fairly simple to grasp: It aims to prohibit discrimination on the basis of color, race, sex, or national origin by state and federal governments, as well as most public places. This larger concept is tackled in 11 titles under the act. In simple terms,

- Title I requires that voting rules and procedures be applied equally to all eligible voters.

- Title II forbids discrimination in “public accommodations” like movie theaters, hotels, and restaurants (though it didn’t go so far as to include private clubs).

- Title III enshrines access for all to public facilities.

- Title IV desegregated public schools and also empowers the Attorney General to file suits to enforce desegregation.

- Title V expanded the S. Commission on Civil Rights, which had been created by the earlier Civil Rights Act of 1957.

- Title VI bans any discrimination by programs that receive federal funds.

- Title VII was constructed to create equal opportunity practices for employment.

- Title VIII was geared toward statistics, making it mandatory to track both voter registration and voting data in places decided upon by the Commission on Civil Rights.

- Title IX (not to be confused with the more-famous Title IX of the Education Amendments Act, which pertains to college sports and beyond) eases the movement of civil rights cases from state courts to federal courts, a rule that was applied because discrimination-based proceedings had a difficult time getting heard in certain states.

- Title X authorized the creation of the Community Relations Service, which is part of the Department of Justice; the service works to mollify community tension and conflicts brought out by acts related to discord between groups in which race, etc. may have played a part.

- Title XI affords protection for defendants of criminal contempt in certain permutations of cases arising from any of the other articles.

No piece of legislation is perfect, but overlooked or unexpected divergences from earlier laws can be corrected or updated in later bills. The Civil Rights Act of 1968 made efforts to address civil rights for Native Americans, as well as tackling housing discrimination in the Fair Housing Act (which is composed of Titles VIII and IX in the text). Labor was addressed in the Civil Rights Act of 1991, guaranteeing the right to a jury trial in cases of discrimination claims while also strengthening the ability of women to sue for sexual harassment or discrimination at work.

Today, inequalities still exist, but the 1964 Civil Rights Act remains one of the most comprehensive attempts to address them. Its passage made possible subsequent legislation, like the Americans with Disabilities Act and the more recent protections afforded to LGBTQ citizens. Our current cultural moment finds us still dealing with fractured communities and the pains of the past. By recognizing these inequities and attempting in some small way to mitigate them, steps like the Civil Rights Act keep us on the path that Kennedy envisioned when he said, “We cannot say to 10 percent of the population that you can’t have that right; that your children cannot have the chance to develop whatever talents they have; that the only way that they are going to get their rights is to go in the street and demonstrate. I think we owe them and we owe ourselves a better country than that.”

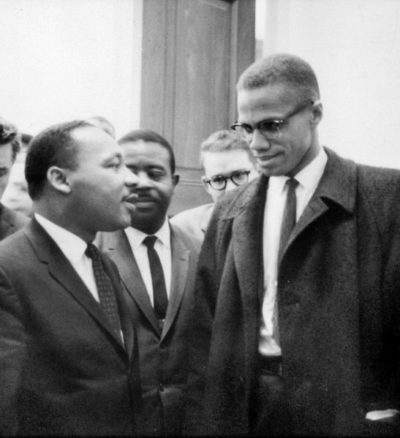

Featured image: President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others observe. (Photo by Cecil Stoughton of the White House Press Office; Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now